World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday, February 23

Parish Health Departments Islandwide Fogging Schedule February 23- February 29, 2020 Sunday, February 23 St. Elizabeth Union Aberdeen Portland Pleasant Hill St. Catherine Tawes Meadows Ellerslie Gardens Hanover Norman Manley Blvd Mt Peto Clarendon Treadlight Treadlight Common St. James Unity Hall Anchovy Kingston & St. Andrew 1 | P a g e Cargill Avenue Balmoral Avenue Kencot Cross Roads Area St. Thomas Eleven Miles Monday, February 24 St. Mary Annotto Bay Roadside (Islington) Top Albany Richmond Road Mile Gully New Road Portland Hector River Township St. Ann Moneague Town Area Silk Street Clinic Street Scot Hill Moneague College compound Manchester Mt Pleasant & Schools Spring Grove & Schools Redberry Baptist Street Old Porus Road Reeveswood Watermouth 2 | P a g e Hanover Orange Bay Mt Peto Westmoreland Amity Pipers Corner Sweet River Trelawny Duanvale Ulster Spring St. James Unity Hall Lethe Clarendon Raymonds Hayes Savannah Monymusk Newtown St. Elizabeth Treasure Beach St. Catherine Seafort Hellshire Heights Cave Hill Braeton 2, 3 & 7 St. Thomas Eleven Miles Kingston & St. Andrew Garages and Tyre Shops Zones 4,5,6 Jones Town- Greenwich Park Road 3 | P a g e Seventh Street Slipe Pen Road Tuesday, February 25 Hanover Green Island Industry Cove Copse Westmoreland Jerusalem Mtn Meylersfield Mtn Trelawny Duanvale Butt-Up Town St. James Coral Gardens Lethe St. Catherine Dover Cherry Byles Fletchers Kingland St. Ann Grants Mountain Manchester 4 | P a g e Plowden Heartease Old England St. Elizabeth Treasure Beach Kingston & St. Andrew Duncaster Bournemouth Gardens Manley Meadows Clarendon Top and Bottom Halse Hall New Bowens Portland Manchioneal St. Mary Enfield Frontier Paggee Tremolesworth Top Road George Town St. -

Supreme Court List for the Week of the 16Th December

Supreme Court of Judicature of Jamaica Civil Division List of Sittings for the week commencing the 16th December 2013 ACTION MATTERS COURT 9 COR: THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE R. KING CLERK: MISS A. MILLS MONDAY 16TH DECEMBER, 2013 2008HCV02744 Richards V Rhoden & Ors Kghn&Kghn:WM:BL:DSP 2010HCV02112 Quest V Wright & Ors 2011HCV03793 Wright V A1 Plumbing & Maintenance (2 days) Services Ltd & Anor TUESDAY 17TH DECEMBER, 2013 2010HCV03190 Beckford V Randle EB:MF&G Partheard (2 days) THURSDAY 19TH DECEMBER, 2013 PETITIONS 2013HCV04998 Dunrobin Plaza Ltd V CMP Home & Office Ltd Petition for Winding Up D-AG&ASSOC 2012HCV02314 Re: CICSA Jamaica Ltd Petition for Winding Up Shellards 2013HCV04370 Douglas V Francis & Anor Petition for Winding Up Company Kghn&Kghn 2012HCV04553 Re: Baker & Sons Construction Descaling Ltd Petition for Winding Up SB&B MOTIONS 2010HCV04604 Registrar of Companies V Banks Trucking Company Ltd Notice of Application for contempt of Court C&S 2007HCV04061 International Asset Services Ltd V Matthews Notice of Application for committal PP:N-BG&F Supreme Court Listing for the week 16th December 2013 Page 1 of 36 (To view the weekly court list please visit our website www.supremecourt.gov.jm.) N.B. The Christmas Term ends on the 20th day of December, 2013. Public Holidays are Christmas Day, Boxing Day and New Years Day – 25th, 26th December, 2013 and 1st January, 2014. The Court and Registry will be closed. The Hillary Term commences on the 7th day of January, 2014. ACTION MATTERS CONT’D 2009HCV01080 Kingston & St. Andrew V Lincolin Notice of Application for contempt of Corporation Court B&B-B:P&CO 2012HCV01892 Richards V The Attorney General of Notice of Motion for contempt of Jamaica Court BB&CO:DSP 2003HCV01213 Adams V Snipe Motion Hearing of Hearing for committal W&S C.L.2001/R000134 Robinson V Anderson UW&CO COURT V COR: THE HONOURABLE MRS. -

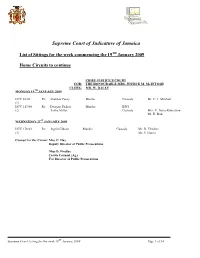

Supreme Court List for the Week of the 19Th January

Supreme Court of Judicature of Jamaica List of Sittings for the week commencing the 19TH January 2009 Home Circuits to continue CHIEF JUSTICE’S COURT COR: THE HONOURABLE MRS. JUSTICE M. McINTOSH CLERK: MR. W. DALEY MONDAY 19TH JANUARY 2009 HCC 28/08 Rv. Sheldon Pusey Murder Custody Mr. C. J. Mitchell (1) HCC 117/08 Rv. Dwayne Pickett Murder BWI (2) Tesha Miller Custody Mrs. V. Neita-Robertson Mr. E. Bird WEDNESDAY 21ST JANUARY 2009 HCC 178/03 Rv. Ingrid Gibson Murder Custody Mr. R. Fletcher (3) Ms. T. Harris Counsel for the Crown: Mrs. C. Hay Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions Miss D. Findlay Crown Counsel (Ag.) For Director of Public Prosecutions Supreme Court Listing for the week 19TH January 2009 Page 1 of 34 COURT II COR: THE HONOURABLE MRS. JUSTICE N. McINTOSH CLERK: MR. O. RAINFORD MONDAY 19TH JANUARY 2009 HCC 76/06 Rv. Negarth Williams Murder Bail Mr. M. Lorne (2) HCC 126/06 Rv. Ricardo Allen Murder Bail Mr. E. Davis (3) Lionel Atkinson Mr. D. Jobson HCC 160/06 Rv. Carlton Brown Murder Custody Mr. T. Tavares-Finson (1) Devon Black Mr. R. Koathes HCC102/07 Rv Shabadine Peart Murder Custody Mr. L. McFarlane (2) Mr. S. Stewart [CA RETRIAL] HCC 177/07 Rv Julian Llewwlyn Murder Bail Offered Mr. L. McFarlane (3) Duran Llewelyn Bail Offered Mr. D. McIntosh-Gayle Peter Williams Bail Offered Mr. P. Shoucair-Gayle WEDNESDAY 21ST JANUARY 2009 HCC 81/04 Rv Omar Johnson Murder Bail Mrs. P. Shoucair-Gayle (1) [HUNG JURY RETRIAL] HCC 210/08 Rv Adrian Morgan Murder Bail Offered Mr. -

The Jamaica Earthquake (1907) Author(S): Vaughan Cornish Source: the Geographical Journal, Vol

The Jamaica Earthquake (1907) Author(s): Vaughan Cornish Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Mar., 1908), pp. 245-271 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1777429 Accessed: 27-06-2016 10:40 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 128.197.26.12 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 10:40:20 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Geographical Journal. No. 3. MARCH, 1908. VOL. XXXI. THE JAMAICA EARTHQUAKE (1907).* By VAUTGHAN CORNISH, D.Sc., F.R.G.S., F.G.S., F.C.S., M.J.S. IN a paper read before the Society in 1899, I introduced the term "K umatology" to define the co-ordinate study of the waves of the lithosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere; and from 1897 to 1907 I have travelled in search of these phenomena, and presented papers upon some of them to the Society. My first experience of seismic waves on an important scale came to me without seeking when I happened to be at Kingston, Jamaica, on January 14, 1907. -

Number of Households by Tenure of Dwelling by Parish, Special Area and Enumeration District: 2011

2011 Census of Population and Housing - Jamaica Table 1.3 Number of Households by Tenure of Dwelling by Parish, Special Area and Enumeration District: 2011 Type of Tenure Total Parish and Special Area Not Dwellings Owned Leased Rented Rent Free Squatted Other Reporte d All Jamaica 881,089 534,353 15,069 176,871 136,835 8,823 1,149 7,989 Kingston 29,513 8,931 375 9,409 9,095 954 65 684 Port Royal 338 136 2 160 25 9 0 6 Harbour View 205 109 7 33 38 0 0 18 Springfield 1,678 950 68 373 193 23 19 52 D'aguilar Town/Rennock Lodge 497 133 0 274 66 0 0 24 Johnson Town 782 234 20 251 205 23 8 41 Norman Gardens 732 200 5 375 120 2 0 30 Bournemouth Gardens 1,172 369 6 610 144 25 0 18 Rollington Town 2,177 555 88 1,001 410 48 19 56 Newton Square 785 185 0 396 169 12 0 23 Passmore Town 1,724 511 19 709 404 27 0 54 Franklyn Town 1,340 287 3 766 257 7 2 18 Campbell Town 548 180 3 251 90 0 2 22 Allman Town 1,461 394 9 566 392 89 0 11 Kingston Gardens 382 76 1 159 135 1 0 10 Fletchers Land 1,431 354 13 391 606 49 0 18 Hannah Town/Craig Town 1,147 316 7 202 574 10 8 30 Denham Town 2,936 934 8 187 1,722 63 0 22 Tivoli Gardens 961 797 8 23 110 6 1 16 Newport East 333 109 1 1 166 39 1 16 East Down Town 3,732 739 62 1,306 1,385 147 1 92 South Side 393 47 4 30 270 23 0 19 Central Down Town 907 103 7 334 379 70 4 10 West Down Town 1,103 170 12 181 708 26 0 6 Manley Meadows 1,632 866 2 412 110 198 0 44 Rae Town 1,117 177 20 418 417 57 0 28 St Andrew 192,112 93,761 4,934 58,225 29,265 2,911 315 2,701 Special Areas 174,799 81,791 4,587 56,363 26,460 2,805 308 2,485 -

International Coastal Cleanup Day Jamaica

INTERNATIONAL COASTAL CLEANUP DAY JAMAICA - SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2016 - SITE LIST* Name of Coordinating Group/Organization Phone Email Cleanup Site Underwater/Land KINGSTON & ST ANDREW Jamaica Environment Trust 960-3693 REGISTRATION IS CLOSED Fort Rocky, Palisadoes Land End of Stones, Palisadoes Land ADM Jamaica Flour Mills Ltd 928-7221 [email protected] Sigarnay Beach Land Caribbean Cement Company Ltd 928-6231-5 [email protected] Rockfort - Harbour side Land Chancellor Hall 475-9058, [email protected] Caribbean Terrace Land 519-7253, 871-9019 Development Foresight Institute 387-7543, [email protected] Port Royal Square (land at left turn to Land 397-3364 go to Gloria's) Drewsland Police Youth Club 364-8027 [email protected] Harbour View Round-a-Bout Land Coastline (Sea Side) Ernst & Young 925-2501 [email protected] Port Royal Beach (behind Gloria's) Land Grace Kennedy Foundation & TAC Campion 932-3541 [email protected] Kingston Harbour Coastline (behind Land College Grace Kennedy Offices) Jamaica Surfing Association 750-0103 [email protected] Bob Marley Beach Land Cable Hut Beach Land JCI Kingston 462-0229 [email protected] Downtown Kingston, Harbour Side Land from Digicel to BOJ Leo Club of Kingston 897-0418, [email protected], Bournemouth Gardens Land 337-9820 [email protected] Mackie Beach Land Rae Town Land National Water Commission 929-1128, [email protected] Harbour View Wastewater Treatment Land 929-5430 Plant Petrojam Ltd 923-8611 [email protected] -

Broadcasting Commission Annual Report 2012 – 2013

Broadcasting Commission Annual Report 2012 – 2013 2 0 1 3 - Broadcasting Commission Annual Report 2012 1 P. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Vision of the Broadcasting Commission...................................................... 4 Mission Statement .................................................................................... 4 Subject Areas.................................................................................................. 4 Profile on Commissioners and Executive Staff Profile on Commissioners................................................................ 7 Profile on Executive Staff................................................................ 10 Profile on Principal Officers............................................................ 10 2 0 1 3 Standing Committees.................................................................................... 11 - Introduction..................................................................................................... 12 Overview of Performance in 2012 – 2013 Public Consultations and Public Education……………………….. 16 o Industry Consultations………………………………………… 16 o Schools’ Outreach…………….. ........................................... 17 o Community Relations…………………………………………. 18 o Citizen-based Media Monitoring……………………………. 19 o Media Campaign……………………………………………… 20 o Publications……………………………………………………… 21 o New Media……………………………………………………… 22 o Media Literacy………………………………………………….. 23 Research ………………………………………………………………. 24 Licensing, Legislative, Statutory Reports, Procurement ………. -

STV Zones Licensed to Be Served.Xlsx

SUBSCRIBER TELEVISION LICENSEES The following is a list of all licensed STV operators in Jamaica and the zones they are licensed to serve. ZONE CODE ZONE NAME LICENSEES Kingston & St. Andrew 01-001 Harbour View Digicel; CTL Ltd.; Flow, DISL 01-002 West Down Town Digicel, DISL,Flow 01-003 Denham Town Digicel, DISL,Flow 01-004 Central Down Town Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 01 – 005 Fletcher’s Land Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 01-006 Allman Town Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 01-007 Campbell Town Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 01-008 East Down Town Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 01-009 Passmore Town Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime; DISL, CTL 01-010 Franklin Town Digicel; Flow; Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 01-011 Rollington Town Digicel; Flow; Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 01-012 Bournemouth Gardens Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 01-013 Norman Gardens Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 01-014 D’Aguilar Town Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 02-015 August Town Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 02-016 Mona Digicel; Flow, Logic One, DISL 02-017 Hope Tavern Digicel; Flow, DISL 02-018 Hope Pastures Digicel; Flow, Logic One, DISL 02-019 Beverly Hills Digicel; Flow., Logic One, DISL 02-020 Barbican Digicel; Flow, Logic One, DISL 02-021 Cherry Gardens Digicel; Flow; DISL 02-022 Grants Pen Digicel; Flow, Logic One ; DISL 02-023 Half-Way-Tree Digicel; Flow, Logic One, DISL 02-024A Trafalgar Park Digicel; Flow; DISL 02-024B New Kingston Digicel; Flow; DISL 02-025 Swallowfield Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 02-026 Vineyard Town Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime, -

SHELTERS STATUS for 2016 HURRICANE SEASON Parish Shelter Name Type (School Etc..) Communities Served (List) Kingston & St

SHELTERS STATUS FOR 2016 HURRICANE SEASON Parish Shelter Name Type (school etc..) Communities Served (list) Kingston & St . Andrew Harbour View Primary (Priority) School Harbour View Kingston & St . Andrew St. Benedicts Primary( Priority) School Harbour View/ Bull Bay Kingston & St . Andrew Friendship Brook All Age (Priority) School Bull Bay/Taylor Land Kingston & St . Andrew Norman Gardens Jnr High School Rockfort/ Norman Gardens Kingston & St . Andrew Rennock Lodge All Age School Rennock Lodge Kingston & St . Andrew Windward Road Junior H. School Windward Road/ Bournemouth Gardens/Burgher Gully (Right Side) Kingston & St . Andrew Holy Rosary Primary School School Windward Road/ Bournemouth Gardens/ Springfield Kingston & St . Andrew Dunoon Technical High School Sirgany/ Burgher Gully (Left side) Kingston & St . Andrew National Arena (Priority) Port Royal, Portmore Kingston & St . Andrew Rollington Town Primary School Rollington Town Kingston & St . Andrew Sir Howard Cooke Centre Community Centre Nannyville/Upper Mountain View Kingston & St . Andrew Gaynstead High School School Swallowfield Kingston & St . Andrew Clan Carthy Primary School School Vineyard Town Kingston & St . Andrew Clan Carthy High School School Vineyard Town Kingston & St . Andrew Franklyn Tn. Primary School Franklyn Town Kingston & St . Andrew Vauxhall Secondary School School Rae Town/ Manley Meadows Kingston & St . Andrew Elleston Road Primary Sch. School Lwr. Franklyn Tn./ Brown's Town Kingston & St . Andrew St. Micheal's Primary School Southside Kingston & St . Andrew Calabar Primary and Junior High School East Queen Street & Environs Kingston & St . Andrew Holy Family Primary Sch. School East Queen Street & Environs Kingston & St . Andrew Kingston Technical High School Hanover Street Kingston & St . Andrew Allman Town Primary School Allman Town Kingston & St . Andrew Alpha Primary School School Camp Road Kingston & St . -

Number of Housing Units, Dwellings and Households by Special Areas for All Parishes: 2011

2011 Census of Population & Housing – Jamaica Table 1.1 Number of Housing Units, Dwellings and Households by Special Areas for All Parishes: 2011 Parish and Special Area Number of Number of Housing Units Number of Dwellings Households All Jamaica 711,331 853,668 881,089 Kingston 14,785 28,835 29,513 Port Royal 160 330 338 Harbour View 154 194 205 Springfield 1,309 1,639 1,678 D'aguilar Town/Rennock Lodge 307 456 497 Johnson Town 514 754 782 Norman Gardens 470 728 732 Bournemouth Gardens 679 1,140 1,172 Rollington Town 1,320 2,116 2,177 Newton Square 446 777 785 Passmore Town 850 1,675 1,724 Franklyn Town 779 1,285 1,340 Campbell Town 365 540 548 Allman Town 797 1,438 1,461 Kingston Gardens 213 377 382 Fletchers Land 611 1,399 1,431 Hannah Town/Craig Town 446 1,119 1,147 Denham Town 1,238 2,887 2,936 Tivoli Gardens 420 907 961 Newport East 91 320 333 East Down Town 1,548 3,679 3,732 South Side 228 386 393 Central Down Town 333 903 907 West Down Town 387 1,100 1,103 Manley Meadows 506 1,607 1,632 Rae Town 614 1,079 1,117 St Andrew 124,775 184,831 192,112 Special Areas 109,777 168,146 174,799 August Town 1,388 1,795 1,902 Hermitage 1,110 1,357 1,437 University 283 446 466 Mona Heights 1,137 1,679 1,891 Elletson Flats/Mona Commons 611 836 923 Hope Tavern 1,166 1,641 1,721 Kintyre 670 793 832 Jacks Hill 889 1,081 1,101 Hope Pastures/Utech 1,182 1,370 1,409 Barbican 2,823 3,943 3,975 Liguanea 2,012 3,564 3,728 Beverley Hills 802 1,427 1,503 Swallowfield 632 987 1,027 Seymour Land 615 1,324 1,352 Trafalgar Park 252 391 394 New Kingston 173 969 -

Population and Housing Census 2011 Jamaica

Population and Housing Census 2011 Jamaica General Report Volume I Copyright © 2012 THE STATISTICAL INSTITUTE OF JAMAICA “Short extracts from this publication may be copied or reproduced, for individual use, with permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. More extensive reproduction or storage in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, requires prior permission of The Statistical Institute of Jamaica.” All rights reserved Published by THE STATISTICAL INSTITUTE OF JAMAICA 7 Cecelio Avenue, Kingston 10, Jamaica. P.O. Box 643 Telephone: (876) 926-5311 Fax: (876) 926-1138 Email: [email protected] Website: www.statinja.gov.jm Table of Contents Preface Acknowledgements Census 2011 Findings ............................................................................................................................................. i Housing Census 2011Findings ......................................................................................................................... xvii Background to the Census ................................................................................................................................ xxix Notes to the Tables .......................................................................................................................................... xxxiii Summary Tables Table 1.1 Population Usually Resident in Jamaica, by Parish: 2011 ............................................................ 2 Table 1.2 Population -

Copy of STV Zones Licensed to Be Served.Xlsx

SUBSCRIBER TELEVISION LICENSEES The following is a list of all licensed STV operators in Jamaica and the zones they are licensed to serve. ZONE CODE ZONE NAME LICENSEES Kingston & St. Andrew 01-001 Harbour View Digicel; CTL Ltd.; Flow, DISL 01-002 West Down Town Digicel, DISL,Flow 01-003 Denham Town Digicel, DISL,Flow 01-004 Central Down Town Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 01 – 005 Fletcher’s Land Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 01-006 Allman Town Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 01-007 Campbell Town Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 01-008 East Down Town Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 01-009 Passmore Town Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime; DISL, CTL 01-010 Franklin Town Digicel; Flow; Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 01-011 Rollington Town Digicel; Flow; Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 01-012 Bournemouth Gardens Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 01-013 Norman Gardens Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 01-014 D’Aguilar Town Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 02-015 August Town Digicel; Flow, DISL, CTL 02-016 Mona Digicel; Flow, Logic One, DISL 02-017 Hope Tavern Digicel; Flow, DISL 02-018 Hope Pastures Digicel; Flow, Logic One, DISL 02-019 Beverly Hills Digicel; Flow., Logic One, DISL 02-020 Barbican Digicel; Flow, Logic One, DISL 02-021 Cherry Gardens Digicel; Flow; DISL 02-022 Grants Pen Digicel; Flow, Logic One ; DISL 02-023 Half-Way-Tree Digicel; Flow, Logic One, DISL 02-024A Trafalgar Park Digicel; Flow; DISL 02-024B New Kingston Digicel; Flow; DISL 02-025 Swallowfield Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime, DISL, CTL 02-026 Vineyard Town Digicel; Flow;Marimaxx/Hometime,