Lower Shabelle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weekly Update on Displacement and Other Population Movements in South-Central Somalia 14 - 20 April 2014 UNHCR Somalia

Weekly update on displacement and other population movements in South-Central Somalia 14 - 20 April 2014 UNHCR Somalia Overview Total estimated IDPs for the week 1,500 In summary, close to 1,500 civilians were displaced during the reporting period. Marka and the outskirts of Mogadishu are now major places of new displacement. IDPs in these Total estimated IDPs since early March 2014 72,700 locations are in need of assistance. ETHIOPIA Ceel Barde Belet Weyne Displacement to Luuq town (Gedo) GALGADUUD According to UNHCR partners, 50 individuals arrived to Luuq from Buurdhuubo (southern Rab dhuure Gedo). The estimated total number of new IDPs in Luuq since the beginning of March is now BAKOOL around 2,450 persons. IDPs from Buurdhuubo are of the same clan as Luuq host Buur dhuxunle Xudur HIRAAN community and are accommodated by extended family members from Luuq. Luuq Waajid Bulo Barde Kurtow Baidoa GEDO Buurdhuubo Buur Hakaba SHABELLE DHEXE Displacement to Baidoa town (Bay) from Bakool region BAY Another 120 IDPs arrived to Baidoa from Bakool region (mainly Wajid district). UNHCR also received reports of the onset of new displacement 150 individuals from Buur dhuxunle BANADIR town in Bakool to the near by villages after SFG attacked the town. Qoryooley Mogadishu SHABELLE HOOSE Marka KENYA JUBA DHEXE Buulo mareer Displacement inside Shabelle Hoose Baraawe Indian Ocean Afmadow Jilib Around 500 civilians arrived to Marka from Qoryooley town over the last couple of days. The total number of new IDPs in Marka is now 9 -9,500 persons. Dobley Region IDP Pop. Legend JUBA HOOSE Bakool 6,990 Main States/Divisions of Origin Kismaayo Banadir 8,350 Bay 16,960 Refugee Camp Displacement to Mogadishu Gedo 3,098 Town, village Hiraan 27,000 Around 400 IDPs from Qoryoley town (Shabelle Hoose) and 250 from Buulo Mareer arrived Major movements to Mogadishu (Km 7-13). -

South and Central Somalia Security Situation, Al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups

1/2017 South and Central Somalia Security Situation, al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups Report based on interviews in Nairobi, Kenya, 3 to 10 December 2016 Copenhagen, March 2017 Danish Immigration Service Ryesgade 53 2100 Copenhagen Ø Phone: 00 45 35 36 66 00 Web: www.newtodenmark.dk E-mail: [email protected] South and Central Somalia: Security Situation, al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups Table of Contents Disclaimer .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction and methodology ......................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations..................................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Security situation ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. The overall security situation ........................................................................................................ 7 1.2. The extent of al-Shabaab control and presence.......................................................................... 10 1.3. Information on the security situation in selected cities/regions ................................................ 11 2. Possible al-Shabaab targets in areas with AMISOM/SNA presence ....................................................... -

2/2014 Update on Security and Protection Issues in Mogadishu And

2/2014 ENG Update on security and protection issues in Mogadishu and South-Central Somalia Including information on the judiciary, issuance of documents, money transfers, marriage procedures and medical treatment Joint report from the Danish Immigration Service’s and the Norwegian Landinfo’s fact finding mission to Nairobi, Kenya and Mogadishu, Somalia 1 to 15 November 2013 Copenhagen, March 2014 LANDINFO Danish Immigration Service Storgata 33a, PB 8108 Dep. Ryesgade 53 0032 Oslo 2100 Copenhagen Ø Phone: +47 23 30 94 70 Phone: 00 45 35 36 66 00 Web: www.landinfo.no Web: www.newtodenmark.dk E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Overview of Danish fact finding reports published in 2012, 2013 and 2014 Update (2) On Entry Procedures At Kurdistan Regional Government Checkpoints (Krg); Residence Procedures In Kurdistan Region Of Iraq (Kri) And Arrival Procedures At Erbil And Suleimaniyah Airports (For Iraqis Travelling From Non-Kri Areas Of Iraq), Joint Report of the Danish Immigration Service/UK Border Agency Fact Finding Mission to Erbil and Dahuk, Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), conducted 11 to 22 November 2011 2012: 1 Security and human rights issues in South-Central Somalia, including Mogadishu, Report from Danish Immigration Service’s fact finding mission to Nairobi, Kenya and Mogadishu, Somalia, 30 January to 19 February 2012 2012: 2 Afghanistan, Country of Origin Information for Use in the Asylum Determination Process, Rapport from Danish Immigration Service’s fact finding mission to Kabul, Afghanistan, 25 February to 4 March -

SOMALIA Food Security Update May 2015

SOMALIA Food Security Outlook Update May 2015 Gu crops developing normally in South-Central KEY MESSAGES Figure 1.Projected food security In Jowhar District in Middle Shabelle and Sablale District in Lower Shabelle Region, outcomes, May to June 2015 flooding in the high-productivity riverine areas will likely lead to a below-average harvest and long delays in that harvest. This will likely increase local cereal prices, reduce agricultural labor demand, and lead to deteriorating food security outcomes between now and the delayed harvest in August. In pastoral areas, increased livestock production and values will likely result in increased access to milk and meat, increased income from milk sales, and better food security between now and September. Northwest Agropastoral livelihood zone will likely have a below-average Gu maize and cash crop harvest in July. Households will likely reduce food consumption between then and the Karan harvest in October. CURRENT SITUATION In mid-April, Gu rains started in South-Central. Since the start, average to above average rainfall was received in most parts of the country. Rains have refilled water catchments, shallow wells, and communal dams in rural areas, and they have Source: FEWS NET helped increase browse availability and improve grazing conditions. Figure 2. Projected food security Several areas have received less rain. The lowest amounts of rain have been in outcomes, July to September 2015 Guban Pastoral livelihood zone in the Northwest and Coastal Deeh Pastoral livelihood zone in Bari Region in the Northeast. Rainfall has also been below average in most parts of Awdal, Bari, Sanag, and Woqooyi Galbeed Regions. -

Clanship, Conflict and Refugees: an Introduction to Somalis in the Horn of Africa

CLANSHIP, CONFLICT AND REFUGEES: AN INTRODUCTION TO SOMALIS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA Guido Ambroso TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE CLAN SYSTEM p. 2 The People, Language and Religion p. 2 The Economic and Socials Systems p. 3 The Dir p. 5 The Darod p. 8 The Hawiye p. 10 Non-Pastoral Clans p. 11 PART II: A HISTORICAL SUMMARY FROM COLONIALISM TO DISINTEGRATION p. 14 The Colonial Scramble for the Horn of Africa and the Darwish Reaction (1880-1935) p. 14 The Boundaries Question p. 16 From the Italian East Africa Empire to Independence (1936-60) p. 18 Democracy and Dictatorship (1960-77) p. 20 The Ogaden War and the Decline of Siyad Barre’s Regime (1977-87) p. 22 Civil War and the Disintegration of Somalia (1988-91) p. 24 From Hope to Despair (1992-99) p. 27 Conflict and Progress in Somaliland (1991-99) p. 31 Eastern Ethiopia from Menelik’s Conquest to Ethnic Federalism (1887-1995) p. 35 The Impact of the Arta Conference and of September the 11th p. 37 PART III: REFUGEES AND RETURNEES IN EASTERN ETHIOPIA AND SOMALILAND p. 42 Refugee Influxes and Camps p. 41 Patterns of Repatriation (1991-99) p. 46 Patterns of Reintegration in the Waqoyi Galbeed and Awdal Regions of Somaliland p. 52 Bibliography p. 62 ANNEXES: CLAN GENEALOGICAL CHARTS Samaal (General/Overview) A. 1 Dir A. 2 Issa A. 2.1 Gadabursi A. 2.2 Isaq A. 2.3 Habar Awal / Isaq A.2.3.1 Garhajis / Isaq A. 2.3.2 Darod (General/ Simplified) A. 3 Ogaden and Marrahan Darod A. -

Food Market and Supply Situation in Southern Somalia

Food Market and Supply Situation in Southern Somalia October 2011 Issa Sanogo 2 Acknowledgement This report is drawn from the findings of a programme mission by Annalisa Conte, Issa Sanogo and Simon Clements from August 30th to September 20th, which was undertaken to assess the suitability of cash-and-voucher based responses in southern Somalia. I wish to acknowledge valuable contributions made by various WFP Headquarters and country office colleagues, namely Rogerio Bonifacio, Oscar Caccavale, Simon Clements, Migena Cumani, Maliki Amadou Mahamane, Nichola Peach, and Francesco Slaviero. Many thanks also to Joyce Luma, Arif Husain and Mario Musa for proof reading the report. Many thanks to the Senior Management of WFP Somalia Country Office, Logistic, Procurement, Programme, Security and VAM staff who provided valuable insights and helped at various stages of this mission. I wish also to thank various partners (INGOs, Local NGOs, UN Organizations, Bilateral and Multilateral Organizations and Technical Partners) and traders for making time available to provide the mission with valuable field updates and perspectives. Secondary data, comments and suggestions provided by FAO, FSNAU and FEWSNET are fully acknowledged. While I acknowledge the contributions made by all the partners in various ways, I take full responsibility for the outcome. 3 I. Summary of Findings ............................................................................................................ 5 II. Markets and Supply Conditions ............................................................................................ -

Mogadishu IDP Influx 28 October 2011 2011 Has Witnessed an Unprecedented Arrival of Idps Into Mogadishu Due to Drought Related Reasons

UNHCR BO Somalia, Nairobi Mogadishu IDP Influx 28 October 2011 2011 has witnessed an unprecedented arrival of IDPs into Mogadishu due to drought related reasons. While the largest influx of IDP s occurred in January 2011, trends indicate that since March, the rate of influx has been steadily increasing. Based on IASC Po pulation Movement Tracking (PMT) data, this analysis aims to identify the key areas receiving IDPs in Mogadishu as well as the source of displacement this year . 1st Quarter 2nd Quarter 3rd Quarter 4th Quarter January to March 2011 April to June 2011 July to September 2011 1 October, 2011 to 28 October 2011 Total IDP Arrivals in Mogadishu 31,400 Total IDP Arrivals in Mogadishu 8,500 Total IDP Arrivals in Mogadishu 35,800 From other areas of Somalia, not including From other areas of Somalia, not including From other areas of Somalia, not including Total IDP Arrivals in Mogadishu 6,800 displacement within Mogadishu. displacement within Mogadishu. displacement within Mogadishu. From other areas of Somalia, not including displacement within Mogadishu. Arrivals by Month Arrivals by Month Arrivals by Month Arrivals by Month 24,200 27,500 6,500 5,700 6,300 6,800 800 1,100 1,700 2,000 January February March April May June July August September October Source of Displacement Reason for Displacement Source of Displacement Reason for Displacement Source of Displacement Reason for Displacement Source of Displacement Where are these IDPs coming from? Why did these people travel to Mogadishu? Why did these people travel to Mogadishu? Why did these people travel to Mogadishu? Where are these IDPs coming from? Where are these IDPs coming from? Where are these IDPs coming from? Eviction During the first quarter, 2,200 people were Reason for Displacement 0 0 reported to have been evicted from IDP settlements 0 Eviction 100 people were reported to have been evicted from 0 Eviction 1 - 99 in the Afgooye corridor and moved to Mogadishu. -

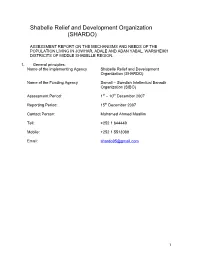

Shabelle Relief and Development Organization (SHARDO)

Shabelle Relief and Development Organization (SHARDO) ASSESSMENT REPORT ON THE MECHANISMS AND NEEDS OF THE POPULATION LIVING IN JOWHAR, ADALE AND ADAN YABAL, WARSHEIKH DISTRICITS OF MIDDLE SHABELLE REGION. 1. General principles: Name of the implementing Agency Shabelle Relief and Development Organization (SHARDO) Name of the Funding Agency Somali – Swedish Intellectual Banadir Organization (SIBO) Assessment Period: 1st – 10th December 2007 Reporting Period: 15th December 2007 Contact Person: Mohamed Ahmed Moallim Tell: +252 1 644449 Mobile: +252 1 5513089 Email: [email protected] 1 2. Contents 1. General Principles Page 1 2. Contents 2 3. Introduction 3 4. General Objective 3 5. Specific Objective 3 6. General and Social demographic, economical Mechanism in Middle Shabelle region 4 1.1 Farmers 5 1.2 Agro – Pastoralists 5 1.3 Adale District 7 1.4 Fishermen 2 3. Introduction: Middle Shabelle is located in the south central zone of Somalia The region borders: Galgadud to the north, Hiran to the West, Lower Shabelle and Banadir regions to the south and the Indian Ocean to the east. A pre – war census estimated the population at 1.4 million and today the regional council claims that the region’s population is 1.6 million. The major clans are predominant Hawie and shiidle. Among hawiye clans: Abgal, Galjecel, monirity include: Mobilen, Hawadle, Kabole and Hilibi. The regional consists of seven (7) districts: Jowhar – the regional capital, Bal’ad, Adale, A/yabal, War sheikh, Runirgon and Mahaday. The region supports livestock production, rain-fed and gravity irrigated agriculture and fisheries, with an annual rainfall between 150 and 500 millimeters covering an area of approximately 60,000 square kilometers, the region has a 400 km coastline on Indian Ocean. -

Somalia 2019 Crime & Safety Report

Somalia 2019 Crime & Safety Report This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Mission to Somalia. The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Somalia at Level 4, indicating travelers should not travel to the country due to crime, terrorism, and piracy. Overall Crime and Safety Situation The U.S. Mission to Somalia does not assume responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons or firms appearing in this report. The American Citizen Services unit (ACS) cannot recommend a particular individual or location, and assumes no responsibility for the quality of service provided. Review OSAC’s Somalia-specific page for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. The U.S. government recommends U.S. citizens avoid travel to Somalia. Terrorist and criminal elements continue to target foreigners and locals in Somalia. Crime Threats There is serious risk from crime in Mogadishu. Violent crime, including assassinations, murder, kidnapping, and armed robbery, is common throughout Somalia, including in Mogadishu. Other Areas of Concern A strong familiarity with Somalia and/or extensive prior travel to the region does not reduce travel risk. Those considering travel to Somalia, including Somaliland and Puntland, should obtain kidnap and recovery insurance, as well as medical evacuation insurance, prior to travel. Inter- clan, inter-factional, and criminal feuding can flare up with little/no warning. After several years of quiet, pirates attacked several ships in 2017 and 2018. -

(I) the SOCIAL STRUCTUBE of Soumn SOMALI TRIB by Virginia I?

(i) THE SOCIAL STRUCTUBE OF SOumN SOMALI TRIB by Virginia I?lling A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London. October 197]. (ii) SDMMARY The subject is the social structure of a southern Somali community of about six thousand people, the Geledi, in the pre-colonial period; and. the manner in which it has reacted to colonial and other modern influences. Part A deals with the pre-colonial situation. Section 1 deals with the historical background up to the nineteenth century, first giving the general geographic and ethnographic setting, to show what elements went to the making of this community, and then giving the Geledj's own account of their history and movement up to that time. Section 2 deals with the structure of the society during the nineteenth century. Successive chapters deal with the basic units and categories into which this community divided both itself and the others with which it was in contact; with their material culture; with economic life; with slavery, which is shown to have been at the foundation of the social order; with the political and legal structure; and with the conduct of war. The chapter on the examines the politico-religious office of the Sheikh or Sultan as the focal point of the community, and how under successive occupants of this position, the Geledi became the dominant power in this part of Somalia. Part B deals with colonial and post-colonial influences. After an outline of the history of Somalia since 1889, with special reference to Geledi, the changes in society brought about by those events are (iii) described. -

Dadaab Returnee Conflict Assessment August 2017

DADAAB RETURNEE CONFLICT ASSESSMENT AUGUST 2017 PREPARED FOR DANISH DEMINING GROUP (DDG) BY KEN MENKHAUS Dadaab Returnee Conflict Assessment | i Foreword and Acknowledgements This conflict assessment was implemented as part of the UK Department for International Development (DFID) funded and Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and Danish Refugee Council (DRC) implemented project: ‘Promoting Durable Solutions through Integrated Return, Reintegration and Resilience Support to Somali Displacement affected Populations’. The project aims to support conditions conducive for safe and dignified return and sustainable reintegration of Somali refugees. The project was implemented between October 2016 and June 2017. The Conflict Assessment was implemented by the Danish Demining Group (DDG), under the supervision of Mads Frilander. The principal investigator and author of the study is Ken Menkhaus, and he alone is responsible for any errors or misinterpretations in the report. He and Ismahan Adawe formed the research team that conducted fieldwork for this study in Mogadishu, Kismayo, Baidoa, and Nairobi in December 2016 and January 2017. The analysis combines existing studies and reports collected in a literature review with over 60 field interviews, as well as a survey carried out in Kismayo. The interviews were semi-structured in format, some held with key informants and others with focus groups of men and women representing host communities, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and returnees. The survey was carried out by the company Researchcare Africa. The research was conducted in challenging security and political conditions, and the research team is deeply indebted to many individuals and organisations who provided essential help to overcome those obstacles. We are also very grateful to the hundreds of Somali stakeholders and international aid officials who volunteered their time to meet with the research team and discuss these issues. -

Trees of Somalia

Trees of Somalia A Field Guide for Development Workers Desmond Mahony Oxfam Research Paper 3 Oxfam (UK and Ireland) © Oxfam (UK and Ireland) 1990 First published 1990 Revised 1991 Reprinted 1994 A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library ISBN 0 85598 109 1 Published by Oxfam (UK and Ireland), 274 Banbury Road, Oxford 0X2 7DZ, UK, in conjunction with the Henry Doubleday Research Association, Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Coventry CV8 3LG, UK Typeset by DTP Solutions, Bullingdon Road, Oxford Printed on environment-friendly paper by Oxfam Print Unit This book converted to digital file in 2010 Contents Acknowledgements IV Introduction Chapter 1. Names, Climatic zones and uses 3 Chapter 2. Tree descriptions 11 Chapter 3. References 189 Chapter 4. Appendix 191 Tables Table 1. Botanical tree names 3 Table 2. Somali tree names 4 Table 3. Somali tree names with regional v< 5 Table 4. Climatic zones 7 Table 5. Trees in order of drought tolerance 8 Table 6. Tree uses 9 Figures Figure 1. Climatic zones (based on altitude a Figure 2. Somali road and settlement map Vll IV Acknowledgements The author would like to acknowledge the assistance provided by the following organisations and individuals: Oxfam UK for funding me to compile these notes; the Henry Doubleday Research Association (UK) for funding the publication costs; the UK ODA forestry personnel for their encouragement and advice; Peter Kuchar and Richard Holt of NRA CRDP of Somalia for encouragement and essential information; Dr Wickens and staff of SEPESAL at Kew Gardens for information, advice and assistance; staff at Kew Herbarium, especially Gwilym Lewis, for practical advice on drawing, and Jan Gillet for his knowledge of Kew*s Botanical Collections and Somalian flora.