What Is Asian German Studies?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT of GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected]

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT OF GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected] POSITIONS Bowdoin College George Taylor Files Professor of Modern Languages, 07/2017 – present Assistant (2002), Associate (2007), Full Professor (2016) in the Department of German, 2002 – present Affiliate Professor, Program in Cinema Studies, 2012 – present Chair of German, 2008 – 2011, fall 2012, 2014 – 2017, 2019 – Acting Chair of Film Studies, 2010 – 2011 Lawrence University Assistant Professor of German, 1998 – 2002 St. Olaf College Visiting Instructor/Assistant Professor, 1997 – 1998 EDUCATION Ph.D. German, Comparative Literature, University of MN, Minneapolis, 1998 M.A. German, University of WI, Madison, 1992 Diplomgermanistik University of Leipzig, Germany, 1991 RESEARCH Books (*peer-review; +editorial board review) 1. Translating the World: Toward a New History of German Literature around 1800, University Park: Penn State UP, 2018; paperback December 2018, also as e-book.* Winner of the SAMLA Studies Book Award – Monograph, 2019 Shortlisted for the Kenshur Prize for the Best Book in Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2019 [reviewed in Choice Jan. 2018; German Quarterly 91.3 (2018) 337-339; The Modern Language Review 113.4 (2018): 297-299; German Studies Review 42.1(2-19): 151-153; Comparative Literary Studies 56.1 (2019): e25-e27, online; Eighteenth Century Studies 52.3 (2019) 371-373; MLQ (2019)80.2: 227-229.; Seminar (2019) 3: 298-301; Lessing Yearbook XLVI (2019): 208-210] 2. Reading and Seeing Ethnic Differences in the Enlightenment: From China to Africa New York: Palgrave, 2007; available as e-book, including by chapter, and paperback.* unofficial Finalist DAAD/GSA Book Prize 2008 [reviewed in Choice Nov. -

A BETTER WAY to BUILD DEMOCRACY Instructor: Doug Mcgetchin, Ph.D

Non-Violent Power in Action A BETTER WAY TO BUILD DEMOCRACY Instructor: Doug McGetchin, Ph.D. Stopping the deportation of Jewish spouses in Nazi Berlin, the liberation of India, fighting for Civil Rights in the U.S., the fall of the Berlin Wall, the ouster of Serbia’s Milosevic and the recent Arab Awakening, all have come about through non-violent means. Most people are unaware of non-violent power, as the use of force gains much greater attention in the press. This lecture explains the effectiveness of non-violent resistance by examining multiple cases of nonviolence struggle with the aim of understanding the principles that led to their success. Using these tools, you can help create a more peaceful and democratic world. Thursday, April 20 • 9:45 –11:15 am $25/member; $35/non-member Doug McGetchin, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of History at Florida Atlantic University where he specializes in the history of the international connections between modern Germany and South Asia. He is the author of “Indology, Indomania, Orientalism: Ancient India’s Rebirth in Modern Germany” (2009) and several edited volumes (2004, 2014) on German-Indian connections. He has presented papers at academic conferences in North America, Europe, and India, including the German Studies Association, the World History Association and the International Conference of Asian Scholars (Berlin). He is a recipient of a Nehru- Fulbright senior research grant to Kolkata (Calcutta), India and a German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) grant to Leipzig, Germany, and has won multiple teaching awards. FOR MORE INFORMATION: Call 561-799-8547 or email [email protected] 5353 Parkside Drive, PA – 134, Jupiter, FL 33458 | www.fau.edu/llsjupiter. -

4.10.2013 > 26.01.2014 PRESS CONFERENCE a Preliminary Outline of the Programme 6 November 2012

4.10.2013 > 26.01.2014 PRESS CONFERENCE A preliminary outline of the programme 6 November 2012 - Palais d’Egmont, Brussels www.europalia.eu 1 PRACTICAL INFORMATION PRESS Inge De Keyser [email protected] T. +32 (0)2.504.91.35 High resolution images can be downloaded from our website www.europalia.eu – under the heading press. No password is needed. You will also find europalia.india on the following social media: www.facebook.com/Europalia www.youtube.com/user/EuropaliaFestival www.flickr.com/photos/europalia/ You can also subscribe to the Europalia- newsletter via our website www.europalia.eu Europalia International aisbl Galerie Ravenstein 4 – 1000 Brussels Info: +32 (0)2.504.91.20 www.europalia.eu 2 WHY INDIA AS GUEST COUNTRY? For its 2013 edition, Europalia has invited India. Europalia has already presented the rich culture of other BRIC countries in previous festivals: europalia.russia in 2005, europalia.china in 2009 and europalia.brasil in 2011. Europalia.india comes as a logical sequel. India has become an important player in today’s globalised world. Spontaneously India is associated with powerful economical driving force. The Indian economy is very attractive and witnesses an explosion of foreign investments. But India is also a great cultural power. The largest democracy in the world is a unique mosaic of peoples, languages, religions and ancient traditions; resulting from 5000 years of history. India is a land of contrasts. A young republic with a modern, liberal economy but also a land with an enormous historical wealth: the dazzling Taj Mahal, the maharajas, beautiful temples and palaces and countless stories to inspire our imagination. -

The Return of the Auslandsdeutscheto Germany in 1919-20

A Forgotten Minority: The Return of the Auslandsdeutsche to Germany in 1919-20 MATTHEW STIBBE Sheffield Hallam University This article examines the expulsion of Germans abroad (Auslandsdeutsche) from Allied countries and colonial empires in the aftermath of the First World War, and their somewhat negative reception in Weimar Germany in 1919-20. It does so against the background of what it identifies as a re-territorialisation of German national identity, beginning during the war itself and leading to an abrupt reversal of previous trends towards the inclusion of Germans abroad within broader transnational notions of Germanness (Deutschtum), rights to citizenship and aspirations to world power status. Re-territorialisation was not born out of the logic of de-territorialisation and Weltpolitik in any dialectical sense, however. Rather, its causes were largely circumstantial: the outbreak of global war in 1914, the worldwide economic and naval blockade of Imperial Germany, and its final defeat in 1918. Nonetheless, its implications were substantial, particularly for the way in which minority German groups living beyond Germany’s new borders were constructed in official and non-official discourses in the period after 1919-20. Keywords: Auslandsdeutsche, citizenship, de-territorialisation, Germans abroad, re-territorialisation Studies on National Movements 5 (2020) | Articles Introduction ‘Coming home’ was a common experience for combatants and civilians from all belligerent nations at the end of the First World War. It was also a process -

Nietzsche's Orientalism

Duncan Large Nietzsche’s Orientalism Abstract: Edward Said may omit the German tradition from his ground-breaking study of Orientalism (1978), but it is clearly appropriate to describe Nietzsche as Orientalist in outlook. Without ever having left Western Europe, or even having read very widely on the subject, he indulges in a series of undiscriminating stereotypes about “Asia” and “the Orient”, borrowing from a range of contemporary sources. His is an uncom- mon Orientalism, though, for his evaluation of supposedly “Oriental” characteristics is generally positive, and they are used as a means to critique European decadence and degeneration. Because he defines the type “Oriental” reactively in opposition to the “European”, though, it is contradictory. Furthermore, on Nietzsche’s analysis “Europe” itself is less a type or a geographical designation than an agonal process of repeated self-overcoming. He reverses the received evaluation of the Europe-Orient opposition only in turn to deconstruct the opposition itself. Europe first emerged out of Asia in Ancient Greece, Nietzsche claims, and it has remained a precarious achieve- ment ever since, repeatedly liable to “re-orientalisation”. He argues that “Oriental” Christianity has held Europe in its sway for too long, but his preferred antidote is a further instance of European “re-orientalisation”, at the hands of the Jews, whose productive self-difference under a unified will he views as the best model for the “good Europeans” of the future. Keywords: Orientalism, Edward Said, Asia, Europe, Christianity, Jews, good Europeans. Zusammenfassung: Auch wenn in Edward Saids bahnbrechender Studie Orienta- lismus (1978) die deutsche Tradition nicht vorkommt, lässt sich Nietzsches Haltung doch als ‚orientalistisch‘ beschreiben. -

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition <UN> Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik Die Reihe wurde 1972 gegründet von Gerd Labroisse Herausgegeben von William Collins Donahue Norbert Otto Eke Martha B. Helfer Sven Kramer VOLUME 86 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/abng <UN> Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition Edited by Lydia Jones Bodo Plachta Gaby Pailer Catherine Karen Roy LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> Cover illustration: Korrekturbögen des “Deutschen Wörterbuchs” aus dem Besitz von Wilhelm Grimm; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Wilhelm Grimm’s proofs of the “Deutsches Wörterbuch” [German Dictionary]; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jones, Lydia, 1982- editor. | Plachta, Bodo, editor. | Pailer, Gaby, editor. Title: Scholarly editing and German literature : revision, revaluation, edition / edited by Lydia Jones, Bodo Plachta, Gaby Pailer, Catherine Karen Roy. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2015. | Series: Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik ; volume 86 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015032933 | ISBN 9789004305441 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: German literature--Criticism, Textual. | Editing--History--20th century. Classification: LCC PT74 .S365 2015 | DDC 808.02/7--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015032933 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 0304-6257 isbn 978-90-04-30544-1 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30547-2 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

18 Au 23 Février

18 au 23 février 2019 Librairie polonaise Centre culturel suisse Paris Goethe-Institut Paris Organisateur : Les Amis du roi des Aulnes www.leroidesaulnes.org Coordination: Katja Petrovic Assistante : Maria Bodmer Lettres d’Europe et d’ailleurs L’écrivain et les bêtes Force est de constater que l’homme et la bête ont en commun un certain nombre de savoir-faire, comme chercher la nourriture et se nourrir, dormir, s’orienter, se reproduire. Comme l’homme, la bête est mue par le désir de survivre, et connaît la finitude. Mais sa présence au monde, non verbale et quasi silencieuse, signifie-t-elle que les bêtes n’ont rien à nous dire ? Que donne à entendre leur présence silencieuse ? Dans le débat contemporain sur la condition de l’animal, son statut dans la société et son comportement, il paraît important d’interroger les littératures européennes sur les représentations des animaux qu’elles transmettent. AR les Amis A des Aulnes du Roi LUNDI 18 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h JEUDI 21 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h LA PAROLE DES ÉCRIVAINS FACE LA PLACE DES BÊTES DANS LA AU SILENCE DES BÊTES LITTÉRATURE Table ronde avec Jean-Christophe Table ronde avec Yiğit Bener, Dorothee Bailly, Eva Meijer, Uwe Timm. Elmiger, Virginie Nuyen. Modération : Francesca Isidori Modération : Norbert Czarny Le plus souvent les hommes voient dans la Entre Les Fables de La Fontaine, bête une espèce silencieuse. Mais cela signi- La Méta morphose de Kafka, les loups qui fie-t-il que les bêtes n’ont rien à dire, à nous hantent les polars de Fred Vargas ou encore dire ? Comment s’articule la parole autour les chats nazis qui persécutent les souris chez de ces êtres sans langage ? Comment les Art Spiegelman, les animaux occupent une écrivains parlent-ils des bêtes ? Quelles voix, place importante dans la littérature. -

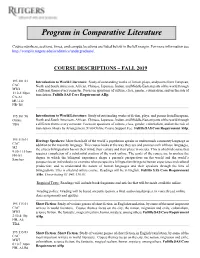

Program in Comparative Literature

Program in Comparative Literature Course numbers, sections, times, and campus locations are listed below in the left margin. For more information see http://complit.rutgers.edu/academics/undergraduate/. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS – FALL 2019 195:101:01 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, CAC North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through MW4 a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of 1:10-2:30pm translation. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. CA-A1 MU-212 HB- B5 195:101:90 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, Online North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through TBA a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of translation. Hours by Arrangement. $100 Online Course Support Fee. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. 195:110:01 Heritage Speakers: More than half of the world’s population speaks or understands a minority language in CAC addition to the majority language. This course looks at the way they use and process each of those languages, M2 the effects bilingualism has on their mind, their culture and their place in society. This is a hybrid course that 9:50-11:10am requires completion of a substantial portion of the work online. The goals of the course are to analyze the FH-A1 degree to which the bilingual experience shape a person's perspectives on the world and the world’s Sanchez perspective on individuals; to examine what perspective bilingualism brings to human experience and cultural production; and to understand the nature of human languages and their speakers through the lens of bilingualism. -

YOKO TAWADA Exhibition Catalogue

VON DER MUTTERSPRACHE ZUR SPRACHMUTTER: YOKO TAWADA’S CREATIVE MULTILINGUALISM AN EXHIBITION ON THE OCCASION OF YOKO TAWADA’S VISIT TO OXFORD AS DAAD WRITER IN RESIDENCE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, TAYLORIAN (VOLTAIRE ROOM) HILARY TERM 2017 ExhiBition Catalogue written By Sheela Mahadevan Edited By Yoko Tawada, Henrike Lähnemann and Chantal Wright Contributed to by Yoko Tawada, Henrike Lähnemann, Chantal Wright, Emma HuBer and ChriStoph Held Photo of Yoko Tawada Photographer: Takeshi Furuya Source: Yoko Tawada 1 Yoko Tawada’s Biography: CABINET 1 Yoko Tawada was born in 1960 in Tokyo, Japan. She began to write as a child, and at the age of twelve, she even bound her texts together in the form of a first book. She learnt German and English at secondary school, and subsequently studied Russian literature at Waseda University in 1982. After this, she intended to go to Russia or Poland to study, since she was interested in European literature, especially Russian literature. However, her university grant to study in Poland was withdrawn in 1980 because of political unrest, and instead, she had the opportunity to work in Hamburg at a book trade company. She came to Europe by ship, then by trans-Siberian rail through the Soviet Union, Poland and the DDR, arriving in Berlin. In 1982, she studied German literature at Hamburg University, and thereafter completed her doctoral work on literature at Zurich University. Among various authors, she studied the poetry of Paul Celan, which she had already read in Japanese. Indeed, she comments on his poetry in an essay entitled ‘Paul Celan liest Japanisch’ in her collection of essays named Talisman and also in her essay entitled ‘Die Niemandsrose’ in the collection Sprachpolizei und Spielpolyglotte. -

The High German of Russian Mennonites in Ontario by Nikolai

The High German of Russian Mennonites in Ontario by Nikolai Penner A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2009 © Nikolai Penner 2009 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract The main focus of this study is the High German language spoken by Russian Mennonites, one of the many groups of German-speaking immigrants in Canada. Although the primary language of most Russian Mennonites is a Low German variety called Plautdietsch, High German has been widely used in Russian Mennonite communities since the end of the eighteenth century and is perceived as one of their mother tongues. The primary objectives of the study are to investigate: 1) when, with whom, and for what purposes the major languages of Russian Mennonites were used by the members of the second and third migration waves (mid 1920s and 1940-50s respectively) and how the situation has changed today; 2) if there are any differences in spoken High German between representatives of the two groups and what these differences can be attributed to; 3) to what extent the High German of the subjects corresponds to the Standard High German. The primary thesis of this project is that different historical events as well as different social and political conditions witnessed by members of these groups both in Russia (e.g. -

Chortitza “Old” Colony, 1789

-being the Magazine/Journal of the Hanover Steinbach Historical Society Inc. Preservings $20.00 No. 20, June, 2002 “A people who have not the pride to record their own history will not long have the virtues to make their history worth recording; and no people who are indifferent to their past need hope to make their future great.” — Jan Gleysteen Chortitza “Old” Colony, 1789 The story of the first settlement of the Flemish Mennonites at the junc- tion of the Chortitza and Dnjepr Riv- ers in 1789 in Imperial Russia is re- plete with drama, tension and trag- edy. It is no small task to establish a peaceful Christian community in an undeveloped steppe and to create an environment where the pioneers and their descendants could thrive and prosper. Within a century the Chortitza “Old” Colony had become perhaps the most prosperous com- munity in the area north of the Black Sea and its industries were leading the way in the region’s booming economy. After some initial faltering the Chortitza Flemish Gemeinde was to become the most stable and flourish- ing of the Mennonites in Russia. It is a precious gift of God to build a large congregation of 4000 and more mem- bers out of a population originating from different Gemeinden and vari- ous regions in the Vistula Delta in Royal Poland and West Prussia. The German Wehrmacht at the entrance to the turbine building of Dnjeproges Hydro-electric dam, June 1941. To God had granted the Flemish pio- the left is the Hydro-electric dam; right, in the rear, the Island of Chortitza with the Mennonite village established neers noble and spirit-filled leaders in 1789; and middle, the bridge over the “new” Dnjepr (east channel). -

German Captured Documents Collection

German Captured Documents Collection A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Allan Teichroew, Fred Bauman, Karen Stuart, and other Manuscript Division Staff with the assistance of David Morris and Alex Sorenson Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2011 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011148 Latest revision: 2012 October Collection Summary Title: German Captured Documents Collection Span Dates: 1766-1945 ID No.: MSS22160 Extent: 249,600 items ; 51 containers plus 3 oversize ; 20.5 linear feet ; 508 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in German with some English and French Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: German documents captured by American military forces after World War II consisting largely of Nazi Party materials, German government and military records, files of several German officials, and some quasi-governmental records. Much of the material is microfilm of originals returned to Germany. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Wiedemann, Fritz, b. 1891. Fritz Wiedemann papers. Organizations Akademie für Deutsches Recht (Germany) Allgemeiner Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund. Deutsches Ausland-Institut. Eher-Verlag. Archiv. Germany. Auswärtiges Amt. Germany. Reichskanzlei. Germany. Reichsministerium für die Besetzten Ostgebiete. Germany. Reichsministerium für Rüstung und Kriegsproduktion. Germany. Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda.