1 a Transgression Too Far: Women Artists and the British Pop Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Painting, 1960

92 Fulham Road, London, SW3 6HR, United Kingdom - Tel: +44 (20) 7584 2200 - Web: www.godsonandcoles.co.uk Sandra Blow ( 1925 - 2006) Painting, 1960 P825 Height: 51 ¼ in (130cm) Width: 57 in (145cm) PROVENANCE Gimpel Fils £ 75000 EXHIBITION North Carolina Museum of Art, September 1964 DESCRIPTION Oil and sand on board Signed and dated verso S Blow 1960 ARTIST'S BIOGRAPHY Sandra Blow (1925 - 2006) was born in London and studied at the St Martins School of Art under Ruskin Spear from 1942 – 1946 and at the Academy in Rome from 1947-1948. In 1961 she won second prize for painting at the John Moores Liverpool exhibition and in the same year began teaching at the Royal College of Art. She has worked in a number of abstract styles, including gestural abstraction and Colour Field Painting, and she has experimented with adding various substances and or objects to the canvas. Sandra Blow considered herself an ‘academic abstract painter’, primarily concerned with such problems as balance and proportion – ‘issues that have been important since art began’. She has exhibited extensively all over the world, notably at The Institute of Contemporary Arts, The Tate Gallery, Camden Arts Centre, Gulbenkian Hall - Royal College of Art, The Hayward Gallery (London), The Royal Institute of Fine Arts (Glasgow), The Tate Gallery St Ives, The Newlyn Art Gallery (Cornwall), Galleria Origine, The Art Foundation (Rome), Palazzo Grassi (Venice), The Art Club (Chicago), Saidenburg Gallery, Albright Knox Gallery, Buffalo (New York), North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh (N. Carolina), The Carnegie Institute (Pittsburg), British Council Travelling Exhibitions to Canada, Australia & New Zealand and in The Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam). -

Intertextuality and the Plea for Plurality in Ali Smith's Autumn

Smithers 1 Intertextuality and the Plea for Plurality in Ali Smith’s Autumn BA Thesis English Language and Culture Annick Smithers 6268218 Supervisor: Simon Cook Second reader: Cathelein Aaftink 26 June 2020 4911 words Smithers 2 Abstract This thesis analyses the way in which intertextuality plays a role in Ali Smith’s Autumn. A discussion of the reception and some readings of the novel show that not much attention has been paid yet to intertextuality in Autumn, or in Smith’s other novels, for that matter. By discussing different theories of the term and highlighting the influence of Bakhtin’s dialogism on intertextuality, this thesis shows that both concepts support an important theme present in Autumn: an awareness and acceptance of different perspectives and voices. Through a close reading, this thesis analyses how this idea is presented in the novel. It argues that Autumn advocates an open-mindedness and shows that, in the novel, this is achieved through a dialogue. This can mainly be seen in scenes where the main characters Elisabeth and Daniel are discussing stories. The novel also shows the reverse of this liberalism: when marginalised voices are silenced. Subsequently, as the story illustrates the state of the UK just before and after the 2016 EU referendum, Autumn demonstrates that the need for a dialogue is more urgent than ever. Smithers 3 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 “A Brexit Novel” ...................................................................................................................... -

Work Placement Handbook

Work Placement Handbook 2012 CONTENTS • Background to Falmouth Art Gallery • Falmouth Art Gallery’s Work placement Policy • Work placement Benefits • Getting the most from the placement • Guidelines General Safety Health Object Handling Supervision • Staff Lists • Forms Falmouth Art Gallery Falmouth Art gallery is a service funded by Falmouth Town Council. It is an accredited museum and complies with standards laid down for the Registration of Museums in the United Kingdom and works in partnership with: Age Concern, The Art Fund, Arts Council England, Brightwater Holidays, Combined Universities of Cornwall, Cornwall and Devon Media, Cornwall College, Cornwall Council Conservation Department, Cornwall Heritage Trust, CSV RSVP, Earls Retreat, Falmouth Arts Society, Falmouth BIDS, Falcare (formerly Mencap), Falmouth Marine School, Falmouth Stroke Club, Heritage Lottery Fund, Hine Downing Solicitors, Jason Thomas Dance Company, Kerrier Pupil Referral Unit, Kids in Museums, Langholme, Little Parc Owles Trust, Local schools, MLA (Museums, Libraries and Archives Council), MLA/V&A Purchase Grant Fund, Museums Association, National Maritime Museum Cornwall, Newquay Zoo, Penlee House Gallery & Museum, Royal Cornwall Museum, Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society, Sully’s Picture Framing Penryn, Susie Group (victims of domestic abuse), Swamp Circus, Tate St Ives, The Tanner Trust, Truro and Penwith College, U3A, University College Falmouth, University of Exeter, Wayfarers,The West End Group – Murdoch and Trevithick Centre, The WILD Young Parents Group Falmouth Art Gallery The Origins of the Collection The first Falmouth Art Gallery was opened in Grove Place in 1894 under the Directorship of William Ayerst Ingram and Henry Scott Tuke. It featured their own work along with that of Sophie Anderson, Richard Harry Carter, Charles Davidson, Topham Davidson, Winifred Freeman and Charles Napier Hemy. -

Aspects of Modern British Art

Austin/Desmond Fine Art GILLIAN AYRES JOHN BANTING WILHELMINA BARNS-GRAHAM DAVID BLACKBURN SANDRA BLOW Aspects of DAVID BOMBERG REG BUTLER Modern ANTHONY CARO PATRICK CAULFIELD British Art PRUNELLA CLOUGH ALAN DAVIE FRANCIS DAVISON TERRY FROST NAUM GABO SAM HAILE RICHARD HAMILTON BARBARA HEPWORTH PATRICK HERON ANTHONY HILL ROGER HILTON IVON HITCHENS DAVID HOCKNEY ANISH KAPOOR PETER LANYON RICHARD LIN MARY MARTIN MARGARET MELLIS ALLAN MILNER HENRY MOORE MARLOW MOSS BEN NICHOLSON WINIFRED NICHOLSON JOHN PIPER MARY POTTER ALAN REYNOLDS BRIDGET RILEY WILLIAM SCOTT JACK SMITH HUMPHREY SPENDER BRYAN WYNTER DAVID BOMBERG (1890-1957) 1 Monastery of Mar Saba, Wadi Kelt, near Jericho, 1926 Coloured chalks Signed and dated lower right, Inscribed verso Monastery of Mar Saba, Wadi Kelt, near Jericho, 1926 by David Bomberg – Authenticated by Lillian Bomberg. 54.6 x 38.1cm Prov: The Artist’s estate Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London ‘David Bomberg once remarked when asked for a definition of painting that it is ‘A tone of day or night and the monument to a memorable hour. It is structure in textures of colour.’ His ‘monuments’, whether oil paintings, pen and wash drawings, or oil sketches on paper, have varied essentially between two kinds of structure. There is the structure built up of clearly defined, tightly bounded forms of the early geometrical-constructivist work; and there is, in contrast, the flowing, richly textured forms of his later period, so characteristic of Bomberg’s landscape painting. These distinctions seem to exist even in the palette: primary colours and heavily saturated hues in the early works, while the later paintings are more subtle, tonally conceived surfaces. -

Bonhams 1793 : Prints

Bonhams 1793 : Prints http://www.bonhams.com/auctions/19781/?list_grid_result=results&print_... Prints Auction 19781 London, Knightsbridge 16 May 2012, starting at 13:00 BST. Sessions This auction is now finished. If you are interested in consigning in future auctions, please contact the specialist department. If you have queries about lots purchased in this auction, please contact customer services. Auction highlights Sold for £13,750 inc. Sold for £8,750 inc. Sold for £8,125 inc. Sold for £5,000 inc. premium premium premium premium Henry George Rushbury, Christopher Richard David Hockney R.A. Patrick Hughes (British, RA, RWS, RE (British, Wynne Nevinson A.R.A. (British, born 1937) Paper born 1939) St. Ives 2007 1889-1968) An Extensive (British, 1889-1946) Les Pools (MCA Tokyo 234) Hand painted multiple with Collection Comprising Bibliophiles Drypoint, Lithograph in colours, lithography, 2007, signed etchings, drypoints and a 1931, on laid, signed in 1980, on Arches cover and numbered 4/45 in ... single wood engraving, pencil, from the ... paper ... various ... 1 Various Artists A Collection of Old Master, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Prints Including a loose sheet album of architectural £ 525 designs, theatrical scenes and some frontispieces such as 'Theatrum Sive Hollandiae' by H.Hondius, plus a collection of miscellaneous prints of portraits, religious, literary and mythological subjects, by various artists including S.Mulinari, W.Walker, J.Collyer, J.Macardell, on various papers, album size 285 x 233mm (11 1/4 x 9 1/8in) Coll -

KS3-5 the Far and the Near International Art in St Ives 6 October 2012 – 13 January 2013

Teacher Resource Notes – KS3-5 The Far and the Near International Art in St Ives 6 October 2012 – 13 January 2013 These notes are designed to support KS3-5 teachers in engaging students as they explore the art work. As well as factual information they provide starting points for discussion, ideas for simple practical activities and suggestions for extended work that could stem from a gallery visit. To book a gallery visit for your group call 01736 796226 or email [email protected]. Season Overview This season Tate St Ives provides an opportunity to view St Ives art alongside British and International modernists such as Henri Matisse, Henry Moore and Jackson Pollock, as well as contemporary artists such as Yto Barrada and Nicholas Hlobo. Over fifty artists from 1900 to today, selected from Tate's global collection, are shown in a series of themed rooms. These open dialogues between the practice of St Ives artists, such as Patrick Heron, Barbara Hepworth, Trevor Bell, Sandra Blow and Alan Davie, and the historic modernist context, as well as contemporary relationships between Modernism and international art. The Heron Mall shows a sculpture by Yto Barrada, raising themes connected with a sense of place, including the aesthetic and political effects of tourism on a location. Gallery 5 considers the artist’s studio, both as a site for abstraction and as a means of framing views of the outside world. It includes paintings Patrick Heron made in his Porthmeor studio, as well as work by Pierre Bonnard and Georges Braque. Gallery 4 explores the connections between painting, Constructivism and architecture. -

Britain in the World 1860–Now

yale center for british art Britain in the World 1860–now Second-floor galleries Rebecca Salter, born 1955, British K37 1996, mixed media on canvas The work of Rebecca Salter draws on a variety of artistic styles, media, and cultural traditions. Her distinctive approach was shaped primarily by the six years she spent in Kyoto, Japan, in the early 1980s, where she studied ceramics. She returned to her native London with a commitment to two-dimensional art and a particular interest in Japanese printmaking techniques and the subtle textures and surfaces of Japanese papers. In the late 1980s, however, she also began to make regular visits to the Lake District in northern England, taking inspiration from the austere landscape and ever-shifting weather conditions. Working within a tight tonal range and rarely letting one part of the canvas speak louder than any other, Salter’s paintings are nonetheless quietly compelling: a suitable match for the architecture of Louis Kahn (designer of the Yale Center for British Art), in whose memory this painting was purchased. Friends of British Art Fund and Gift of Jules David Prown, MAH 1971, in memory of Louis I. Kahn, B2011.8 Sandra Blow, 1925–2006, British Red Circle 1960, mixed media on board Sandra Blow emerged in the 1950s as one of the most innovative figures in British abstract art. Blow built her reputation as an independent and pioneering force despite making and keeping a loose connection to the modernists at St. Ives, especially Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, and Patrick Heron. Red Circle’s vivid band of color encircling concentric black rings on a monochrome field exemplifies her bold abstraction, which nevertheless references the natural world and organic forms. -

Reverberations Modern Art in St Ives 9–26 February 2018

Reverberations Modern Art in St Ives 9–26 February 2018 22 Fore Street, St Ives, Cornwall TR26 1HE 01736 794888 [email protected] www.belgravestives.co.uk Follow us on Twitter and Instagram: @belgravestives #artstives KENNETH ARMITAGE CBE W. BARNSBGRAHAM CBE 1 2 TREVOR BELL SANDRA BLOW 3 4 ALAN DAVIE PAUL FEILER 5 6 SIR TERRY FROST PATRICK HAYMAN 7 8 BARBARA HEPWORTH DBE PATRICK HERON CBE 9 10 PATRICK HERON CBE ROGER HILTON CBE 11 12 BEN NICHOLSON OM KATE NICHOLSON 13 14 VICTOR PASMORE CH CBE JOHN WELLS 15 16 Page 1 Page 5 KENNETH ARMITAGE CBE 1916 –2002 Printed at Curwen Studios, this image relates closely to Armitage’s ALAN DAVIE 1920 –2014 Alan Davie’s work often incorporated mysterious symbols drawn Seated Group / 1960 Geometry of Fear sculpture of the 1950s, which portrayed joined Tiwi Spirit Study / 1997 from a wide range of sources, from American Indian pottery, maps, Lithograph / 40 x 58 cm (sheet) figures, often in groups, cast in bronze as single pieces. There are Gouache on paper / 46.5 x 59.5 cm ancient rock-carvings and Aboriginal art. The title of this gouache several examples in the Tate Collection, which also includes a copy from 1997 suggests a connection with the Tiwi Islands of Australia’s Unsigned proof aside from edition of 300 Signed, titled and dated of this lithograph. Northern Territories, whose Aboriginal culture created wooden Curwen Studio stamp on reverse Provenance: Private Collection carvings, often depicting birds from Tiwi mythology. Pictured with 1960s Ernest Race ‘Antelope Chair’ , Price: £1,000 designed in 1951 for the Festival of Britain: £550 Price: £4,500 Pictured with Marcel Breuer Bent Plywood ‘Isokon’ Table: £550 and ‘Vase’ in the style of Joanna Constantinides: £250 Page 2 Page 6 W. -

Winter 2020 Contents

Yale Yale Autumn & Winter 2020 Autumn & Yale AUTUMN & WINTER 2020 Contents General Interest Highlights | Hardback 1–21 General Interest Highlights | Paperback 22–28 Art 2, 4, 26, 29–60, 67 fashion & textile 30, 34, 53 architecture 32, 47, 48, 50, 59 design & decorative 29, 31, 33, 35, 48–51, 58, 59 modern & contemporary 37, 40–42, 45, 46, 51–54, 59, 60 18th & 19th century 36, 37, 43, 54, 56 15th, 16 th & 17th century 40, 44, 45, 54, 56, 57 ancient & antiquity 48, 49, 57–59 collections & theory 44, 46, 58, 59, 60 Mathematics, Science & Medicine 21, 22, 63, 72 Business & Economics 7, 11, 12, 61 History 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 14, 15, 20–28, 62–64, 74–76 Biography & Memoir 2, 4, 5, 9, 16, 17, 23, 26, 47, 65, 75 Philosophy, Theology & Jewish Studies 9, 13, 65–68 Film, Performing Arts, Literary Studies 8, 13, 16, 17, 24–27, 52, 65, 69–71 International Affairs & Political Science 3, 10, 18, 19, 28, 61, 62, 64 American Studies 28, 74–76 Psychology, Social & Environmental Science 16, 22, 60, 62, 63, 73, 76 Picture Credits & Index 77–79 Sales Contacts 80 Ordering Information 81 Rights, Inspection Copy, Review Copy Information 81 Yale University Press YaleBooks 47 Bedford Square @yalebooks London WC1B 3DP tel 020 7079 4900 yalebooksblog.co.uk general email [email protected] www.yalebooks.co.uk A thrilling history of MI9 – the WWII organisation that engineered the escape of Allied forces from behind enemy lines MI9 A History of The Secret Service for Escape and Evasion in World War Two Helen Fry Helen Fry is a specialist in the When Allied fighters were trapped behind enemy lines, one branch of history of British Intelligence. -

Frank Bowling on the Most Random Object That Has Ended up in His Paintings

Frank Bowling on the most random object that has ended up in his paintings By Poppy Malby 4 August 2019 Presenting everything you need to know about the life long friend of Francis Bacon, Frank Bowling now at Tate Britain Frank Bowling isn't a name that's spent much time in the spotlight of the public art world. But over the past 60 years he has been working alongside contemporaries such as Patrick Caulfield, David Hockney and Pauline Boty. It is only now, after his current exhibition at Tate Britain, that Bowling is getting the focus that he deserves. Bowling's work predominantly consists of pop- inflicted canvases with a hint of expressionism that some may associate with the style of the late Basquiat. However, during the Sixties, when Bowling moved from England to New York, he soon learnt what he was missing and found himself restricted by the stereotype that art needs to tell a story. Instead, Bowling drifted to create works touched by personal memory and history. “I was the stool pigeon to help the necessary pacifying for the awfulness of colonialism,” he says. “I represented the black world, so to speak.” One can get lost in his figurative pop art, which portray all sorts of textures. Read on to find out the most random object that has ended up in one of Bowling’s paintings… 1. Where were you born? I was born in Bartica, in what used to be British Guyana, at the confluence of the Cuyuni, Mazaruni and Essequibo rivers. 2. What did you want to be when you were growing up? When I first moved to England I wanted to be a poet. -

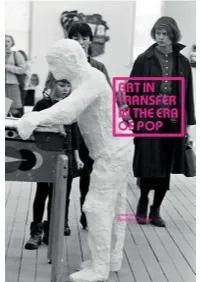

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the -

Feminism Reframed Alexandra M. Kokoli Cambridge Scholars

Feminism Reframed Edited by Alexandra M. Kokoli Cambridge Scholars Publishing Feminism Reframed, Edited by Alexandra M. Kokoli This book first published 2008 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing 15 Angerton Gardens, Newcastle, NE5 2JA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2008 by Alexandra M. Kokoli and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-84718-405-7, ISBN (13): 9781847184054 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Looking On, Bouncing Back Alexandra M. Kokoli Section I: On Exhibition(s): Institutions, Curatorship, Representation Chapter One............................................................................................... 20 Women Artists, Feminism and the Museum: Beyond the Blockbuster Retrospective Joanne Heath Chapter Two.............................................................................................. 41 Why Have There Been No Great Women Dadaists? Ruth Hemus Chapter Three............................................................................................ 61 “Draws Like a Girl”: The Necessity of Old-School Feminist Interventions in the World of Comics and Graphic Novels