Feminism Reframed Alexandra M. Kokoli Cambridge Scholars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC SCULPTURE LOCATIONS Introduction to the PHOTOGRAPHY: 17 Daniel Portnoy PUBLIC Public Sculpture Collection Sid Hoeltzell SCULPTURE 18

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VIRGINIO FERRARI RAFAEL CONSUEGRA UNKNOWN ARTIST DALE CHIHULY THERMAN STATOM WILLIAM DICKEY KING JEAN CLAUDE RIGAUD b. 1937, Verona, Italy b. 1941, Havana, Cuba Bust of José Martí, not dated b. 1941, Tacoma, Washington b. 1953, United States b. 1925, Jacksonville, Florida b. 1945, Haiti Lives and works in Chicago, Illinois Lives and works in Miami, Florida bronze Persian and Horn Chandelier, 2005 Creation Ladder, 1992 Lives and works in East Hampton, New York Lives and works in Miami, Florida Unity, not dated Quito, not dated Collection of the University of Miami glass glass on metal base Up There, ca. 1971 Composition in Circumference, ca. 1981 bronze steel and paint Location: Casa Bacardi Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Carol and Richard S. Fine aluminum steel and paint Collection of the University of Miami Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Camner Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center University of Miami University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Blake King, 2004.20 Gift of Dr. Maurice Rich, 2003.14 Location: Wellness Center Location: Pentland Tower 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 JANE WASHBURN LEONARDO NIERMAN RALPH HURST LEONARDO NIERMAN LEOPOLDO RICHTER LINDA HOWARD JOEL PERLMAN b. United States b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1918, Decatur, Indiana b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1896, Großauheim, Germany b. 1934, Evanston, Illinois b. -

Chryssa B. 1933, Athens D. 2013, Athens New York Times 1975–78

Chryssa b. 1933, Athens d. 2013, Athens New York Times 1975–78 Oil and graphite on canvas Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Michael Bennett 80.2717 Chryssa began making stamped paintings based on the New York Times in 1958 and continued to do so into the 1970s. To create these works, she had rubber stamps produced based on portions of the newspaper before, as she described it, covering “the entire area [of a canvas] with a fragment repeated precisely.” Over time Chryssa’s treatment of the motif became increasingly abstract, as she more strictly adhered to a gridded composition and selected sections of newsprint with type too small to be legibly rendered in rubber. By deemphasizing the content and format of the newspaper, she redirected focus to the tension between mechanized reproduction and her careful process of stamping by hand. Jacob El Hanani b. 1947, Casablanca Untitled #171 1976–77 Ink and acrylic on canvas Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Mr. and Mrs. George M. Jaffin 77.2291 With its dense profusion of finely drawn lines, Jacob El Hanani’s Untitled #171 is a feat of physical endurance, patience, and precision. As the artist said, “It is a personal challenge to bring drawing to the extreme and see how far my eyes and fingers can go.” Rather than approach this effort as an end unto itself, El Hanani has often related it to Jewish traditions of handwriting religious texts—a parallel suggesting a desire to transcend the self through a devotional level of discipline. This aspiration is given form in the way the short, variously weighted lines lose their discreteness from afar and blend into a vaporous whole. -

The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1995 ARTIST'S CHOICE: ELIZABETH MURRAY June 20 - August 22, 1995 An exhibition conceived and installed by American artist Elizabeth Murray is the fifth in The Museum of Modern Art's series of ARTIST'S CHOICE exhibitions. On view from June 20 to August 22, 1995, ARTIST'S CHOICE: ELIZABETH MURRAY presents more than 100 drawings, paintings, prints, and sculptures by approximately seventy women artists. The exhibition involves works created between 1914 and 1973, including those ranging from early modernists Frida Kahlo and Liubov Popova to contemporary artists Nancy Graves and Dorothea Rockburne. Murray focuses particular attention on artists who made their reputations during the 1950s and 1960s, such as Lee Bontecou, Agnes Martin, Joan Mitchell, when Murray herself was studying and forming her style. This exhibition and the accompanying video and panel discussion are made possible by a generous grant from The Charles A. Dana Foundation. Organized in collaboration with Kirk Varnedoe, Chief Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture, the ARTIST'S CHOICE series invites artists to create an exhibition from the Museum's collection according to a personally chosen theme or principle. "I wanted, for myself, to explore what being a woman in the art world has meant," Murray writes in the exhibition brochure. "I wanted to weave together a sense of the genuine and profound contribution women's work has made to the art of our time." - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Fax: 212-708-9889 2 Installed in the Museum's third-floor contemporary painting and sculpture galleries, the exhibition is arranged in thematic groupings. -

Yuki Jungesblut Rola Khayyat and Ahmed Zidan Sharon Paz Petra Spielhagen Chryssa Tsampazi Travel, Time Zones, Jet Lag, Departures

PERSONAL TERRITORIES Yuki Jungesblut Rola Khayyat And Ahmed Zidan Sharon Paz Petra Spielhagen Chryssa Tsampazi Travel, time zones, jet lag, departures. The disquiet of our globalised lives changes us. We have to stand our ground in constantly changing circumstances. What we have to do, where we have to go, what time we have to arrive — it is often our calendar that dictates all this. But where are we, who are we and what belongs to us? PERSONAL TERRITORIES is an exhibition by six international artists whose works pose questions of how we move — con- tinually crossing borders, blurring time, meeting changing expectations. Photographs, videos, installations and performances prompt reflection on borders, borders as barriers, borders as portals to the unknown — and reflection on lack of boundaries. Physically bounded territories become readable as symbols, the effect of symbolic boundaries on the intimacy of the body. The artists move as travellers, experimenters, seekers of refuge, correspondents. Ortswechsel, Zeitzonen, Jetlag, Trennungen. Die Unruhe un- seres globalisierten Lebens verändert uns. Wir müs sen uns in beständig wechselnden Situationen behaupten. Was wir tun müssen, wohin wir reisen, wann wir an kommen müssen, sagt uns oft der Terminkalender. Wo aber sind wir, wer sind wir, was gehört uns? In der Ausstellung PERSONAL TERRITORIES stellen sechs internationale Künstler mit ihren Arbeiten die Frage, wie wir uns in der beständigen Überschreitung von Grenzen, dem Verschwimmen der Zeitfolgen und der fließen den Verän- derung von Erwartungen bewegen. Fotografien, Videos, Installationen und Performances regen Reflexionen über Grenzen an, Grenzen als Schran ken, Gren- zen als Tore zum Unbekannten – und Reflexionen über das Fehlen von Grenzen. -

Contemporary Art As an Educational Resource: the Cockerline Collection

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Faculty Publications School of Design 2013 Contemporary Art as an Educational Resource: The oC ckerline Collection Leda Cempellin South Dakota State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/design_pubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Cempellin, Leda. "Contemporary Art as an Educational Resource: The ockC erline Collection." Cockerline Collection: Prints of the 60s, 70s, and 80s. South Dakota Art Museum, 2013: 7-9 Print. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Design at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contemporary Art as an Educational Resource; The Cockerline Collection From an eager college printmaking international scene, Cockerline originally student in Michigan to a major collector envisioned a collection that would of prints, Neil Cockerline has embraced educate future Michigan art students his educational mission by providing by providing a multi-faceted context as students with direct exposure to great art. inspiration for their own work. By including The adventure started during Cockerline's the offshoot of Abstract Expressionism, early formative years at Alma College in Color Field, Hard-Edge Abstraction, Michigan (1977-1981), in an exchange Pop Art, New Realism, Photorealism, of academic work with his mentor, Conceptual Art, plus several artists printmaker Kent Kirby. -

Intertextuality and the Plea for Plurality in Ali Smith's Autumn

Smithers 1 Intertextuality and the Plea for Plurality in Ali Smith’s Autumn BA Thesis English Language and Culture Annick Smithers 6268218 Supervisor: Simon Cook Second reader: Cathelein Aaftink 26 June 2020 4911 words Smithers 2 Abstract This thesis analyses the way in which intertextuality plays a role in Ali Smith’s Autumn. A discussion of the reception and some readings of the novel show that not much attention has been paid yet to intertextuality in Autumn, or in Smith’s other novels, for that matter. By discussing different theories of the term and highlighting the influence of Bakhtin’s dialogism on intertextuality, this thesis shows that both concepts support an important theme present in Autumn: an awareness and acceptance of different perspectives and voices. Through a close reading, this thesis analyses how this idea is presented in the novel. It argues that Autumn advocates an open-mindedness and shows that, in the novel, this is achieved through a dialogue. This can mainly be seen in scenes where the main characters Elisabeth and Daniel are discussing stories. The novel also shows the reverse of this liberalism: when marginalised voices are silenced. Subsequently, as the story illustrates the state of the UK just before and after the 2016 EU referendum, Autumn demonstrates that the need for a dialogue is more urgent than ever. Smithers 3 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 “A Brexit Novel” ...................................................................................................................... -

New York State Office of General Services Art Conservation and Restoration Services – Solicitation Number 1444

Request for Proposals (RFP) are being solicited by the New York State Office of General Services For Art Conservation and Restoration Services January 29, 2009 Class Codes: 82 Group Number: 80107 Solicitation Number: 1444 Contract Period: Three years with Two One-Year Renewal Options Proposals Due: Thursday, March 12, 2009 Designated Contact: Beth S. Maus, Purchasing Officer NYS Office of General Services Corning Tower, 40th Floor Empire State Plaza Albany, New York 12242 Voice: 1-518-474-5981 Fax: 1-518-473-2844 Email: [email protected] New York State Office of General Services Art Conservation and Restoration Services – Solicitation Number 1444 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Designated Contact..................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Minimum Bidder Qualifications.................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Pre-Bid Conference..................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Key Events .................................................................................................................................. 5 2. PROPOSAL SUBMISSION......................................................................................................... -

The National Life Story Collection

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH FASHION Betty Jackson Interviewed by Eva Simmons C1046/10 IMPORTANT Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 [0]20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. NATIONAL LIFE STORY COLLECTION INTERVIEW SUMMARY SHEET Title Page Ref. No.: C1046/10/01-26 Playback No: F15711, F16089-92, F16724- 8, F16989-96, F17511-8 Collection title: Oral History of British Fashion Interviewee’s surname: Jackson Title: Ms Interviewee’s forenames: Betty Sex: F Occupation: Fashion Designer Date of birth: 1949 Mother’s occupation: Housewife Father’s occupation: Shoe Manufacturer Date(s) of recording: 14.07.04, 29.09.04, 20.10.04, 25.11.04, 02.12.04, 14.01.05, 25.02.05, 08.04.05, 22.04.05, 06.05.05, 03.06.05, 27.06.05 Location of interview: Betty Jackson’s office, Shepherds Bush, London Name of interviewer: Eva Simmons Type of recorder: Marantz CP430 Total no. of tapes: 26 Type of tape: D60 Mono or stereo: Stereo Speed: N/A Noise reduction: Dolby B Original or copy: Original Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: open Interviewer’s comments: Betty Jackson Page 1 C1046/10 Tape 1 Side A (part 1) Tape 1 Side A [part 1] This is Eva Simmons interviewing Betty Jackson. -

Winter 2020 Contents

Yale Yale Autumn & Winter 2020 Autumn & Yale AUTUMN & WINTER 2020 Contents General Interest Highlights | Hardback 1–21 General Interest Highlights | Paperback 22–28 Art 2, 4, 26, 29–60, 67 fashion & textile 30, 34, 53 architecture 32, 47, 48, 50, 59 design & decorative 29, 31, 33, 35, 48–51, 58, 59 modern & contemporary 37, 40–42, 45, 46, 51–54, 59, 60 18th & 19th century 36, 37, 43, 54, 56 15th, 16 th & 17th century 40, 44, 45, 54, 56, 57 ancient & antiquity 48, 49, 57–59 collections & theory 44, 46, 58, 59, 60 Mathematics, Science & Medicine 21, 22, 63, 72 Business & Economics 7, 11, 12, 61 History 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 14, 15, 20–28, 62–64, 74–76 Biography & Memoir 2, 4, 5, 9, 16, 17, 23, 26, 47, 65, 75 Philosophy, Theology & Jewish Studies 9, 13, 65–68 Film, Performing Arts, Literary Studies 8, 13, 16, 17, 24–27, 52, 65, 69–71 International Affairs & Political Science 3, 10, 18, 19, 28, 61, 62, 64 American Studies 28, 74–76 Psychology, Social & Environmental Science 16, 22, 60, 62, 63, 73, 76 Picture Credits & Index 77–79 Sales Contacts 80 Ordering Information 81 Rights, Inspection Copy, Review Copy Information 81 Yale University Press YaleBooks 47 Bedford Square @yalebooks London WC1B 3DP tel 020 7079 4900 yalebooksblog.co.uk general email [email protected] www.yalebooks.co.uk A thrilling history of MI9 – the WWII organisation that engineered the escape of Allied forces from behind enemy lines MI9 A History of The Secret Service for Escape and Evasion in World War Two Helen Fry Helen Fry is a specialist in the When Allied fighters were trapped behind enemy lines, one branch of history of British Intelligence. -

Frank Bowling on the Most Random Object That Has Ended up in His Paintings

Frank Bowling on the most random object that has ended up in his paintings By Poppy Malby 4 August 2019 Presenting everything you need to know about the life long friend of Francis Bacon, Frank Bowling now at Tate Britain Frank Bowling isn't a name that's spent much time in the spotlight of the public art world. But over the past 60 years he has been working alongside contemporaries such as Patrick Caulfield, David Hockney and Pauline Boty. It is only now, after his current exhibition at Tate Britain, that Bowling is getting the focus that he deserves. Bowling's work predominantly consists of pop- inflicted canvases with a hint of expressionism that some may associate with the style of the late Basquiat. However, during the Sixties, when Bowling moved from England to New York, he soon learnt what he was missing and found himself restricted by the stereotype that art needs to tell a story. Instead, Bowling drifted to create works touched by personal memory and history. “I was the stool pigeon to help the necessary pacifying for the awfulness of colonialism,” he says. “I represented the black world, so to speak.” One can get lost in his figurative pop art, which portray all sorts of textures. Read on to find out the most random object that has ended up in one of Bowling’s paintings… 1. Where were you born? I was born in Bartica, in what used to be British Guyana, at the confluence of the Cuyuni, Mazaruni and Essequibo rivers. 2. What did you want to be when you were growing up? When I first moved to England I wanted to be a poet. -

David Hockney

DAVID HOCKNEY David Hockney (b. 1937) • Born in Bradford, went to Bradford Grammar School and Bradford College of Art. He was born with synaesthesia and sees colours in response to music. At the Royal College of Art he met R. B. Kitaj • 1961 Young Contemporaries exhibition announcing the arrival of British Pop art. His early work shows expressionist elements similar to some Francis Bacon. He exhibited alongside Peter Blake (born 1932), Patrick Caulfield and Allen Jones. He met Ossie Clarke and Andy Warhol. • He featured in Ken Russell’s Pop Goes the Weasel with Pauline Boty (pronounced ‘boat-ee’) • Hockney had his first one-man show when he was 26 in 1963, and by 1970 (or 1971) the Whitechapel Gallery in London had organized the first of several major retrospectives. • He moved to Los Angeles in 1964, London 1968-73 and then Paris 1973-75. He produced 1967 paintings A Bigger Splash and A Lawn Being Sprinkled. Los Angeles again in 1978 rented then bought the canyon house and extended it. He also bought a beach house in Malibu. He moved between New York, London and Paris before settling in California in 1982. • He was openly gay and painted many celebratory works. It 1964 he met the model 1 Peter Schlesinger and was romantically involved. In California he switched from oils to acrylic using smooth, flat and brilliant colours. • He made prints, took photographs and stage design work for Glyndebourne, La Scala and the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. • From 1968 he painted portraits of friends just under life size. -

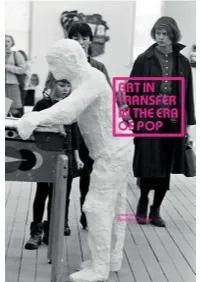

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the