The National Life Story Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

1960S Fashion Opposition to the Vietnam War by the Young and an Age of Social Protest—Led to New, Radically Different Youthful Clothing Styles

1950s, Mother and Daughter Styles 1960s fashion Opposition to the Vietnam War by the young and an age of social protest—led to new, radically different youthful clothing styles 1960 1967 1960’s: Mary Quant invents the miniskirt and helps to usher in a new age… She supported the anti-parent philosophy of life as fun “Working class design, British fashion, Rock and Roll, The Beatles, Carnaby Street…all of a sudden everything came together.” Robert Orbach Lesley Hornby= Twiggy In the 60’s Fashion became central to a young person’s identity • Known for the high fashion mod look created by Mary Quant • Twiggy changed the world of fashion with her short-haired, androgynous look • Embodiment of Youth-quake generation • Face of the decade • Wide-eyed elfin features and slight builds— hence her nickname • Her style has dominated the runways for forty years • She was also famous for drawing long, fake eyelashes under her bottom lashes. These are, unsurprisingly, named “Twiggys.” • Twiggy was regarded as one of the faces of 1960s Swinging London 1960’s model Twiggy recreates the flapper look of the 1920’s. Two revolutionary decades for women and fashion New fabrics that contributed to new clothing styles • Polyester: easy-care, easy-to-wear • New fabrics were comfortable to the touch, wrinkle free, and care free • Perfect match for simple miniskirts and short tunic dresses of the era • Vinyl (also called PVC) was a shiny, wet- look plastic, easy to color and print with flamboyant designs. Was used at first for outerwear then for everything including -

Broadclough Hall

Broadclough Hall Broadclough Hall situated on Burnley Road, Bacup was the home of the Whittaker family for many years, the Whitaker family came to Bacup in 1523. James Whittaker of Broadclough was Greave of the forest in 1559 and his grandfather had also been a Greave in 1515. The present Broadclough Hall is dated to about 1816 and was the third Broadclough Hall erected on the same site by the Whittaker family; the two previous halls were thought to have been half-timbered structures. Some of the giant oak timbers were at one time used as fencing in the ground of the hall. In 1892 a giant oak said to be 500 years old was blown down during one winter storm. James Whittaker who was born 1 Nov 1789 was the town’s first magistrate qualifying in 1824. He married Harriet Ormerod whose father owned Waterbarn Mill. The Whittaker family owned at least 50 farms in the area, principally on the hillsides around Bacup and the Lumb Valley. Houses known as the Club Houses and many of the shops between Rochdale Road and Newchurch Road belonged to the family. James Whittaker died on the 19th April 1855 aged 65, John his eldest son born about 1830 also became a local magistrate being appointed on the 5th July 1855. He married the eldest daughter of Robert Munn owner of Heath Hill Stacksteads, Elizabeth Ann Munn. In 1887 it was reported in the Bacup Times that the house was to be let, unfurnished with house stables and pleasure grounds attached it would make an ideal home for one of Bacup’s many benefactors. -

Chapter XIX Old Houses and Old Families Spotland

CHAPTER XIX . Oft 3ousea and bid Samif es.-'4rotfand . HEALEY HALL. ANDS "assarted" out of the wastes of this part of Spotland were at a very early period known as Heleya, or Heley, and gave their name to a family long resident there. Some- time in the twelfth century Dolphin de Heleya was living here ; he had three sons-Henry, Adam and Andrew. John, the son of Henry, had issue two sons, Andrew and Adam ; he died about the year 1272, seised of a messuage at Heleya.l Adam, the son of Dolphin, confirmed to his brother Henry lands in Castleton early in the next century, and his name as a witness appears frequently in charters relating to lands in Whitworth about 1238, as do also those of Adam the son of William de Heleya, William the son of Peter de Heleya, and Henry de Heleya.2 In 1273 Henry de Merlond granted land to John de Heleya, on the marriage of Amicia his daughter to Andrew the son of John de Heleya .3 There was also then living Richard the son of Anketillus de Heleya, who granted a bovate of land in Heleya to Stanlawe ; probably it was the same Anketillus the son of Andrew chaplain of Rochdale, who by deed without date confirmed to his brother Clement a bovate of land in Heleya and an " assart " which his brother Alexander had " assarted." There was also Robert, son of Anketillus, who granted to Stanlawe lands in Heleya which he had from his father, Clement de Heleya.4 Sometime before the close of the thirteenth century [c . -

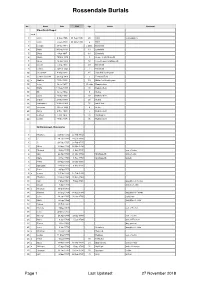

Edenfield Chapel.Numbers-Burials

Rossendale Burials No. Name Date Died Age Abode Comment Edenfield Chapel used 1 John 2 Sep 1785 31 Aug 1785 20 Ed’d consumption 2 John 2 Jun 1799 31 May 1789 2 Ed’d 3 Joseph 27 Apr 1814 2 mths Edenfield 4 Nelly 30 Sep 1814 19 Edenfield 5 Betty 4 Apr 1817 inf Edenfield 6 Maria 28 Mar 1824 3 Hobbo in Shuttleworth 7 Alice 16 Jun 1824 38 Top of Lee in Shuttleworth 8 Susan 5 Sep 1833 inf Edenfield 9 James 14 Feb 1841 1 Edenfield 10 Susannah 8 May 1841 15 Hark Mill Haslingden 11 James Howarth 23 Aug 1856 5 Townend Fold 12 x Matilda 11 Oct 1856 19 Water-foot Haslingden 13 John 18 Jul 1857 15 mths Ramsbottom 14 Betty 13 Sep 1857 40 Ramsbottom 15 Eli 12 Jul 1862 8 Holme 16 Jane 16 Apr 1866 28 Ramsbottom 17 Sarah 24 Oct 1868 20 Holme 18 Emmanuel 28 Nov 1868 32 Irwell Vale 19 Susanna 26 Feb 1869 8 Holme 20 Betty 4 Dec 1869 5 Ramsbottom 21 Samuel 5 Oct 1876 56 Haslingden 22 James 19 Oct 1876 36 Ramsbottom St Emmanuel, Holcombe 1 Thomas 24 Feb 1732 22 Feb 1732 2 ? 25 Jan 1737 23 Jan 1737 1 ? 24 Feb 1737 24 Feb 1737 2 Alice 12 Mar 1738 10 Mar 1738 3 Richard 2 Aug 1747 1 Aug 1747 son of John 4 Ann 23 Apr 1750 21 Mar 1750 Shuttleworth wife of John 5 Mary 8 Dec 1750 6 Dec 1750 Shuttleworth widow 6 Betty 31 Mar 1755 29 Mar 1755 7 Margaret 8 Nov 1756 6 Nov 1756 8 Peter 8 Feb 1757 9 x Esther 17 Feb 1760 15 Feb 1760 10 Thomas 22 Aug 1760 20 Aug 1760 11 Ann 7 May 1761 7 May 1761 daughter of Peeter 12 Susan 9 Apr 1763 widow of John 13 x Thomas 19 Oct 1763 14 Genney 16 Aug 1764 14 Aug 1764 daughter of Peeter 15 John 28 Jan 1765 26 Jan 1765 ould John 16 Mary 8 Sep -

Fashion in The

1 Sheffield U3A 1960s Fashion Project: What We Wore Sheffield U3A 60s Project 2018 – Fashion Group narrative 2 This document has been compiled by members of the Sheffield University of the Third Age (SU3A) who formed a Fashion Group as part of a wider Remembering the 1960s project. The group met regularly during 2018, sharing memories, photographs and often actual items of clothing that they wore during the 1960s, when most of the group were teenagers or young adults. The 1960s was a very exciting time to be a young fashion-conscious person, with most having enough spare cash to enjoy the many new styles pouring out of the waves of creativity which characterised the decade in so many ways. New easy-care fabrics became available, and cloth was still cheap enough to enable most women to copy the latest designs by making garments at home. In fact, the ubiquity of home-dressmaking was a key factor which emerged from our project and represents one of the biggest changes in everyday clothing between the 1960s and 50 years later. In those days almost every family had someone skilful enough make their own garments, and doing so was generally less expensive than buying clothing. Many books and a wealth of information and online resources are now available for students of 1960s fashion history and it is not our intention here to repeat that well-documented narrative. Instead we wanted to tell our own stories and record our personal recollections of our favourite outfits and memories associated with them. We did this by sharing and talking about our photographs, by showing each other garments and accessories we have kept and treasured, by reminiscing, and by writing up those reminiscences. -

Rossendale Commercial Property Register

Rossendale Commercial Property Register Industrial Property & Premises Garages Land for Development Leisure Premises Office Accommodation Retail Premises Businesses for Sale Investment Opportunities CONTENTS Unit Type Page Bacup Garage 1 Industrial 3 Leisure & Tourism 5 Office 6 Other 8 Retail 9 Edenfield Land 13 Office 14 Haslingden Industrial 15 Land 21 Office 22 Other 27 Retail 28 Rawtenstall Industrial 30 Investment 37 Land 38 Leisure & Tourism 39 Office 41 Retail 50 Stubbins Industrial 55 Waterfoot Industrial 56 Leisure & Tourism 59 Office 60 Retail 61 Showroom 64 Storage Unit 65 Whitworth Industrial 66 Responsible Corporate Support Version Version 57 Team/Section Responsible Author Gwen Marlow Date for Review End Nov 2018 Last Updated 18 Sept 2018 Rossendale Commercial Property Register Bacup Garage Reference: 25502 Status: AVAILABLE Address: Glen Services, Newchurch Road, Bacup, OL13 0NN Min Size: 412 SqM Min Size: 4,435 SqFt Max size: 412 SqM Max size: 4,435 SqFt Usage: Garage Tenure: Freehold Contact Agent Categories: Agents: • Petty Chartered Surveyors Car Parking: Unknown Main Contact Tel: 01282 456677 Description: Comprising of an existing showroom and adjoining single storey workshop. The showroom is fully glazed with a frontage to Newchurch Road and adjacent is a substantial forecourt that has been used for motor vehicle sales. Included on the site was an original detached bungalow, part of which was converted to provide office accommodation, however it has been vacant for some time and is in need of refurbishment. The whole site extends to approximately 1.3 acres and offers potential for redevelopment, subject to obtaining the necessary planning consent. Accommodation Showroom & offices 124.5 sq m (1,339 sq ft) Workshop 38.5 sq m (414 sq ft) First floor stores 55.6 sq m (598 sq ft) Detached bungalow 99 sq m (1,900 sq ft) The property has a substantial frontage to Newchurch Road (A681), the main arterial route between Rawtentsall and Bacup town centre. -

Fashion Revolutionary Mary Quant Comes to Tāmaki Makaurau in a Major Exhibition This Summer

MEDIA RELEASE WEDNESDAY 11 AUGUST 2021 Fashion revolutionary Mary Quant comes to Tāmaki Makaurau in a major exhibition this summer Mary Quant and Vidal Sassoon, 1964. © Ronald Dumont/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Image ‘It is given to a fortunate few to be born at the right time, in the right place, with the right talents. In recent fashion there are three: Chanel, Dior and Mary Quant.’ – Ernestine Carter An international exhibition exploring the work of legendary fashion designer Mary Quant is set to open at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki this summer. Here from the V&A in London, Mary Quant takes a look at the fashion icon who harnessed the youthful spirit of the sixties and embraced new mass production techniques to create a new look for modern women. Auckland Art Gallery Director Kirsten Lacy is excited to share the fashion revolutionary and youthquake of the 1960s with New Zealanders through an exhibition that cleverly explores Quant’s transformative effect on the fashion scene. ‘Mary Quant was all about revolution. She dressed the liberated woman with her fun, youthful and creative designs. Quant made designer fashion affordable for working women, overturning the dominance of luxury couture from Paris,’ says Lacy. Famously modelled by Twiggy, Grace Coddington and more, Mary Quant’s clothes personified the energy and fun of swinging London and Quant became a powerful role model for the working woman. Challenging conventions, she is known as the face of the miniskirt and popularised colourful tights and tailored trousers – encouraging a new age of feminism. Inspiring young women to rebel against traditional dress worn by their mothers and grandmothers, Quant turned a tiny boutique on the King’s Road, London, into a wholesale brand available in department stores across the UK, US, Europe and Australia. -

The Swinging Sixties

The Swinging Sixties 3 Leggi i brani e rispondi alle domande. The idea of ‘teenagers’, with their own style of clothes and music, originated in the USA in the 1950s. Rock and Roll was born there, and Elvis Presley was the first global rock star. People all around the world are still interested in American music, films and celebrities. But in the 1960s, Britain, not the USA, was the centre of the world’s pop culture! Music The Beatles were the best-selling British band in history and their influence on modern music is enormous. They were international superstars in the 1960s and they had millions of fans. It was often impossible to hear the music at Beatles’ concerts because of the screaming! But there were lots of other very successful British pop groups in that decade and the trendiest place in the world was ‘Swinging’ London. The UK’s capital city was the home of the Rolling Stones and lots of other pop stars. The Beatles moved there from Liverpool in 1963 and worked at the famous recording studios on Abbey Road. Glossary screaming urla swinging vivace, dinamica, alla moda recording studios studi di registrazione 1 Where did the idea of ‘teenagers’ originate? 2 What was the name of the best-selling British band in history? 3 When did the Beatles move to London? 4 Where were their recording studios in London? Go Live! Level 2 Culture C, pp.212–213 © Oxford University Press PHOTOCOPIABLE Fashion The biggest fashion invention of the 1960s was the miniskirt. Girls in the 1950s wore long, wide skirts, but in 1964 everything changed. -

Lancashire Bird Report 2005

Lancashire & Cheshire Fauna Society Publication No. 108 Lancashire Bird Report 2005 The Birds of Lancashire and North Merseyside S. J. White (Editor) D. A. Bickerton, A. Bunting, S. Dunstan, R. Harris C. Liggett, B. McCarthy, P. J. Marsh, S.J. Martin, J. F. Wright. 2 Lancashire Bird Report 2005 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................... Dave Bickerton & Steve White ......... 2 Review of the Year ...................................................................... John Wright ....... 11 Systematic List Wildfowl ................................................................................ Charlie Liggett ....... 16 Gamebirds ................................................................................Steve Martin ....... 35 Divers to cormorants .................................................................. Bob Harris ....... 39 Herons to birds of prey .................................................... Stephen Dunstan ....... 45 Rails ...........................................................................................Steve Martin ....... 53 Oystercatcher to plovers ...................................................... Andy Bunting ....... 56 Knot to Woodcock ................................................................ Charlie Liggett ....... 61 Godwits to phalaropes .............................................................. Steve White ....... 66 Skuas ........................................................................................... Pete Marsh ....... 73 Gulls ...................................................................................... -

Op in Vogue Elena Galleani D'agliano 2020

OP IN VOGUE ELENA GALLEANIELENA D’AGLIANO 2020 Op in Vogue Elena Galleani d’Agliano Op in Vogue Master Thesis by Elena Galleani d’Agliano Supervised by Jérémie Cerman Printed at Progetto Immagine, Torino MA Space and Communication HEAD Genève October 2019 Vorrei ringraziare il mio tutor Jérémie per avermi seguito in questi mesi, Sébastien e Laurence per il loro indispensabile aiuto al Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Oliver and Anna per avermi dato una mano con l’inglese, Alexandra e gli altri tutor per i loro incoraggiamenti e la mia famiglia per il loro instancabile supporto. 5 10 18 34 43 87 108 88 A glimse of the Sixties 90 The Optical Woman Portfolio 91 The diffusion of Architectural 64 prêt a porter Defining Op 44 The Guy visions in Mulas 18 92 Economic impli- fashion Bourdin’s elegance 67 Who are you, 34 Fashion pho- cations 11 Definition of The relation- 48 The youth quake William Klein? 21 tography in the 96 Basis for further Op Art according to Bailey Franco Rubar- ship with the Sixties 70 experimentations: 13 The influen- source 52 The female telli, the storyteller 36 Defining Op the Space Age Style ces Op art and emancipation throu- 74 Swinging with 27 photography 102 The heritage 108 Epilogue 14 Exhibitions its representation gh the lens of Hel- Ronald Traeger 83 Advertising mut Newton today 111 Bibliography and diffusion on Vogue 78 Others 57 Monumentality in Irving Penn 60 In the search of other worlds with Henry Clarke Prologue The Op Op Fashion Sociological Epilogue fashion photography implications 7 8 9 Prologue early sixty years ago, mum diffusion, 1965 and 1966. -

Lancashire Textile Mills Rapid Assessment Survey 2010

Lancashire Textile Mills Lancashire Rapid Assessment Survey Oxford Archaeology North March 2010 Lancashire County Council and English Heritage Issue No: 2009-10/1038 OA North Job No: L10020 Lancashire Textile Mills: Rapid Assessment Survey Final Report 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................. 5 1. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Project Background ..................................................................................... 6 1.2 Variation for Blackburn with Darwen........................................................... 8 1.3 Historical Background.................................................................................. 8 2. ORIGINAL RESEARCH AIMS AND OBJECTIVES...................................................10 2.1 Research Aims ........................................................................................... 10 2.2 Objectives .................................................................................................. 10 2.3 Blackburn with Darwen Buildings’ Digitisation .......................................... 11 3. METHODOLOGY..................................................................................................12 3.1 Project Scope............................................................................................