Aspects of Modern British Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First-Ever Exhibition of British Pop Art in London

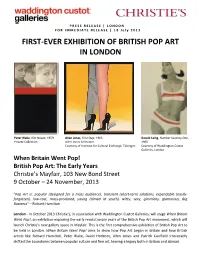

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 1 8 J u l y 2 0 1 3 FIRST- EVER EXHIBITION OF BRITISH POP ART IN LONDON Peter Blake, Kim Novak, 1959 Allen Jones, First Step, 1966 Gerald Laing, Number Seventy-One, Private Collection Allen Jones Collection 1965 Courtesy of Institute for Cultural Exchange, Tübingen Courtesy of Waddington Custot Galleries, London When Britain Went Pop! British Pop Art: The Early Years Christie’s Mayfair, 103 New Bond Street 9 October – 24 November, 2013 "Pop Art is: popular (designed for a mass audience), transient (short-term solution), expendable (easily- forgotten), low-cost, mass-produced, young (aimed at youth), witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, Big Business" – Richard Hamilton London - In October 2013 Christie’s, in association with Waddington Custot Galleries, will stage When Britain Went Pop!, an exhibition exploring the early revolutionary years of the British Pop Art movement, which will launch Christie's new gallery space in Mayfair. This is the first comprehensive exhibition of British Pop Art to be held in London. When Britain Went Pop! aims to show how Pop Art began in Britain and how British artists like Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake, David Hockney, Allen Jones and Patrick Caulfield irrevocably shifted the boundaries between popular culture and fine art, leaving a legacy both in Britain and abroad. British Pop Art was last explored in depth in the UK in 1991 as part of the Royal Academy’s survey exhibition of International Pop Art. This exhibition seeks to bring a fresh engagement with an influential movement long celebrated by collectors and museums alike, but many of whose artists have been overlooked in recent years. -

The Roberts Robert Macbryde (1913-1966) and Robert Colquhoun (1914-1962) 3 – 31 March 2010

The Roberts The Roberts Robert MacBryde (1913-1966) and Robert Colquhoun (1914-1962) 3 – 31 March 2010 Introduction 3 Time for Reappraisal by Davy Brown 7 Two Bright Guests by Robin Muir 10 Biographies 41 Acknowledgements 44 Front Cover: Photographs of Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun by John Deakin (1951) courtesy Vogue/© The Condé Nast Publications Ltd. Above: Photograph of Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun by Felix Man (1949) Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Bedford Gardens studio. Left: Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun in Regent Street, London. Early 1950s: Baron Collection: Hulton Archive 2 Introduction Whilst doing some research for another of Art in the 1930s. They moved to London in exhibition, I found an L S Lowry catalogue from 1941 and quickly became associated with the 1944, called ‘The Industrial North and its People’, Neo-Romantic group of painters which included held at The Scottish Gallery. It was a chance find Keith Vaughan and John Minton. At a time when with unforeseen consequences. How exactly homosexuality was not only illegal but actively did the gallery survive during wartime and in persecuted, they made little attempt to disguise particular, what artists did we show and what their relationship and they had a constant stream social and artistic changes could clearly be of admirers, both male and female. The circle established? I pulled the entire library apart to of friends that grew around them included the find more clues. The result is that I now have too painters Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Michael many stories to tell, but on this day I found all the Ayrton, John Minton and the poets George Barker catalogues that belonged to ‘The Starks’. -

Helios by Gillian Ayres

Helios by Gillian Ayres A talk by Amanda Phillips, Learning and Access Officer at Leeds Art Gallery This is the first of a series of short talks made for the exhibition Natural Encounters by staff and volunteers working at Leeds Art Gallery. Different voices share their ideas about one single artwork on display for our online audiences to enjoy as a personal interpretation that can add to their own. I have been asked share the first, which I’ve titled… Reading ‘Helios’ by Gillian Ayres. Up close this artwork is extraordinary. The paint is so thickly applied that it comes together in wave-top crests, with different colours meeting in mark-making that touches and then falls away. The effect blends colour in the mind’s eye, and supports the work of the imagination as it makes meaning. Helios by Gillian Ayres was produced in 1990, and is understood within the naming-systems of the art world as an Abstract painting. Currently it is displayed in the gallery’s ‘Natural Encounters’ exhibition, curated from Leeds’ art collections to explore the idea of human relationships with the natural world. The painting entered into the collection in 1991, not that long after she had painted it. In the gallery’s file of correspondence and other material linked to the artwork, is a letter that makes clear two options for purchase were on the table. Reading between the lines, it would seem that a member of the then gallery team had travelled to London in the winter of 1990 to see an exhibition of the artist’s new work, at an independent gallery owned by her then dealer. -

Bideford Bay (1946) David Bomberg

Chapter 5: Compositional Effects of Color Color (hue, chroma and value) effect the perception of space… …both 2D… (shapes can be made to seem larger or smaller by altering color) …and 3D (advancing and receding). The size of colored regions also effects the perceived color (larger areas seem brighter). Aerial Perspective or Atmospheric Perspective • (both phrases refer to the same phenomena – they are interchangeable terms) • Several color effects can be described in terms of Aerial perspective. • — Colors tend to be lighter and lower in chroma in the distance. (color moves closer to sky color) • — Contrast in value diminishes in the distance. (value range diminishes in distance) • — Sharp contrasting edge tends to bring (at least) one surface forward. (sharp detail or edges advance forms; blurred forms recede) The Space Between • The physical cause of atmospheric perspective in nature is dust and moisture in the air. • These scattered particles diffuse light, thereby softening the appearance of distant objects and causing their color to move closer to the prevailing sky color. • The Moisture-filled Space Between • Fog is an atmosphere densely filled with moisture – atmospheric perspective can be apparent at a very short distance. • Albert Bierstadt’s 19th c. paintings of the American West were composed to express the vast space open to expansion. • Aerial Perspective • Lighter values, reduced contrast, lower chroma all tend to establish a sense receding (distant) space. • Limited structure and detail are present — there are David Bomberg no linear perspective clues to structure, location, size or distance. Yet there is a definite sense of space— near regions and far regions. -

Sculpting Lives S1E1, Barbara Hepworth

Sculpting Lives podcast transcript Series 1, Episode 1: Barbara Hepworth This document is an accessible transcript of the podcast audio. Subscribe and listen: https://audioboom.com/posts/7525504-sculpting-lives-barbara-hepworth [music] Sara Matson: She managed her brand, fair play. Eleanor Clayton: A normal person from Wakefield; A remarkable artist but a remarkable woman. Stephen Feeke: Hepworth was odd because she didn't see herself as a feminist at all and didn't see herself as “I'm a pioneering woman”. She just felt she was a pioneering sculptor. Barbara Hepworth: I was born with the ideas of certain shapes in my mind. At least I remember as far back as seven. The whole time one's been working at it and working, trying to simplify and make more mature, get the right scale, and develop it according to the development of society. [music] Jo Baring: Hello, and welcome to Sculpting Lives the podcast by me, Jo Baring. Sarah Victoria Turner: And me, Sarah Turner. Jo, this is our first podcast and episode. Why are we doing this? Jo Baring: We met in our professional lives. You are Deputy Director of the Paul Mellon Centre, and I am Director of the Ingram Collection. We have a shared interest in art, but we realised when we met that we are really fascinated by sculpture in particular. Also, during the course of our discussions, we realised that women artists and women sculptors, in general, are less commercially successful than men, less represented in national institutions, museums, possibly have less gallery shows and we really wanted to unpick why that happens. -

Ivon Hitchens & His Lasting Influence

Ivon Hitchens & his lasting influence Ivon Hitchens & his lasting influence 29 June - 27 July 2019 An exhibition of works by Ivon Hitchens (1893-1979) and some of those he influenced 12 Northgate, Chichester West Susssex PO19 1BA +44 (0)1243 528401 / 07794 416569 [email protected] www.candidastevens.com Open Wed - Sat 10-5pm & By appointment “But see Hitchens at full pitch and his vision is like the weather, like all the damp vegetable colours of the English countryside and its sedgy places brushed mysteriously together and then realised. It is abstract painting of unmistakable accuracy.” – Unquiet Landscape (p.145 Christopher Neve) The work of British painter Ivon Hitchens (1893 – 1979) is much-loved for his highly distinctive style in which great swathes of colour sweep across the long panoramic canvases that were to define his career. He sought to express the inner harmony and rhythm of landscape, the experience, not of how things look but rather how they feel. A true pioneer of the abstracted vision of landscape, his portrayal of the English countryside surrounding his home in West Sussex would go on to form one of the key ideas of British Mod- ernism in the 20thCentury. A founding member of the Seven & Five Society, the influential group of painters and sculptors that was responsible for bringing the ideas of the European avant-garde to London in the 30s, Hitchens was progres- sive long before the evolution of his more abstracted style post-war. Early on he felt a compulsion to move away from the traditional pictorial language of art school and towards the development of a personal language. -

The Joan and Lester Avnet Collection in the Museum of Modern Art : Exhibited, Apr

A Treasury of modern drawing : the Joan and Lester Avnet Collection in the Museum of Modern Art : exhibited, Apr. 27-July 4, 1978 William S. Lieberman Date 1978 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art ISBN 08707060980 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2355 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art A TREASURY OF MODERN I DRAWING THE JOANAND LESTER AVNET COLLECTION Archive MoMA 1210 ft TREASURY OF MODERN DRAWING A TREASURY OF MODERN DRAWING THE JOANAND LESTER AVNET COLLECTION IN THE MUSEUMOF MODERNART WILLIAMS.LIEBERMAN THE MUSEUM OFMODERN ART, NEW YORK 4«-CH'«C lAOrf/) 12-10 MUSEUM OF MODERNART LIBRARY Copyright © 1978 by The Museum of Modern Art All rights reserved The Museum of Modern Art 11 West 53 Street New York, N.Y. 10019 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 78-50658 ISBN: 0-87070-609-8 Designed by Steven Schoenfelder Printed by Meriden Gravure Co., Meriden, Conn. Bound by Sendor Bindery, Inc., New York, N.Y. Printed in the United States of America cover Matisse: The Necklace. 1950. Brush and ink, ioVz x i6Vi" frontispiece Feininger: The Town ofLegefeld. 1916. Pen and ink, charcoal, 9 Vi x 12V2" INTRODUCTION 7 ILLUSTRATIONS 35 CA TALOG OF THE COLLECTION 108 Lester Avnet was a devoted son, brother, husband, and father. His life was dedicated to his family; indeed he thought more often of them, always with pride, than he did of himself. -

R.B. Kitaj: Obsessions

PRESS RELEASE 2012 R.B. Kitaj: Obsessions The Art of Identity (21 Feb - 16 June 2013) Jewish Museum London Analyst for Our Time (23 Feb - 16 June 2013) Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, West Sussex A major retrospective exhibition of the work of R. B. R.B. Kitaj, Juan de la Cruz, 1967, Oil on canvas, Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo; If Not, Not, 1975, Oil and black chalk on canvas, Scottish Kitaj (1932-2007) - one of the most significant National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh © R.B. Kitaj Estate. painters of the post-war period – displayed concurrently in two major venues for its only UK showing. Later he enrolled at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford, and then, in 1959, he went to the Royal College of Art in This international touring show is the first major London, where he was a contemporary of artists such as retrospective exhibition in the UK since the artist’s Patrick Caulfield and David Hockney, the latter of whom controversial Tate show in the mid-1990s and the first remained his closest painter friend throughout his life. comprehensive exhibition of the artist’s oeuvre since his death in 2007. Comprised of more than 70 works, R.B. During the 1960s Kitaj, together with his friends Francis Kitaj: Obsessions comes to the UK from the Jewish Museum Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Lucian Freud were Berlin and will be shown concurrently at Pallant House instrumental in pioneering a new, figurative art which defied Gallery, Chichester and the Jewish Museum London. the trend in abstraction and conceptualism. -

Damien Hirst E Il Mercato Dell'arte Contemporanea: La Carriera Di Un Young British Artist

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Economia e Gestione delle Arti e delle attività culturali Tesi di Laurea DAMIEN HIRST E IL MERCATO DELL'ARTE CONTEMPORANEA: LA CARRIERA DI UN YOUNG BRITISH ARTIST Relatore Prof. Stefania Portinari Laureanda Martina Pellizzer Matricola 816581 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 1 INDICE INTRODUZIONE p. 3 CAPITOLO 1 ALCUNE RIFLESSIONI SUL MERCATO DELL'ARTE CONTEMPORANEA: ISTITUZIONI E STRUTTURE DI PROMOZIONE E VENDITA 1 L'Evoluzione del sistema delle gallerie e della figura del gallerista p. 3 2. Il ruolo dei musei p. 19 3 Il ruolo dei collezionisti p. 28 4 Le case d'asta p. 36 CAPITOLO 2 DAMIEN HIRST: DA A THOUSAND YEARS (1990) A FOR THE LOVE OF GOD (2007) 1 Il sistema dell'arte inglese negli anni Novanta: gli Young British Artist …........p. 41 2 Damien Hirst una carriera in ascesa, da “Frezze” alla retrospettiva presso la Tate Modern p. 47 3 I galleristi di Damien Hirst p. 67 CAPITOLO 3 IL RUOLO DEL MERCATO DELL'ARTE NELLA CARRIERA DI DAMIEN HIRST 1 L'asta di Sotheby's: “Beautiful inside my head forever” p. 78 2 Rapporto tra esposizione e valore delle opere dal 2009 al 2012..............................p. 97 CONCLUSIONI p. 117 APPENDICE p. 120 BIBLIOGRAFIA p. 137 2 INTRODUZIONE Questa tesi di laurea magistrale si pone come obiettivo di analizzare la carriera dell'artista inglese Damien Hirst mettendo in evidenza il ruolo che il mercato dell'arte ha avuto nella sua carriera. Il primo capitolo, dal titolo “Alcuni riflessioni sul mercato dell'arte contemporanea”, propone una breve disanima sul funzionamento del mercato dell'arte contemporanea, analizzando in particolar modo il ruolo di collezionisti, galleristi, istituzioni museali e case d'asta, tutti soggetti in grado di influenzare notevolmente la carriera di un artista, anche se in maniera differente. -

The M.O.M.A. and Great Britain

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART November 18, 1959 11 WEST 53 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART AND GREAT BRITAIN The Museum of Modern Art, which has just announced a campaign to raise 25 million ( dollars for additional building and program funds, has played an important role in worldwide f cultural exchange since its founding in 1929. This activity has been increased in recent years I with the establishment of the International Program, a special department in the Museum de- I voted to cultural exchange* The importance of this activity to men and women all over I America is attested by the fact that the Museum's Program is now under the auspices of an I international Council composed of community leaders and art patrons from many parts of the I country. The Museum from its early years has carried on an active exchange program with I Great Britain which began with the acquisition of works by British artists. Among the sculp- I tors represented in the Museum Collections are: Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Lynn I Chadwick, Jacob Epstein, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and Eduardo Paolossi. Painters I include, among others: Francis Bacon, John Bratby, Alan Davie, Luclan Freud, Gwen John, I Wyndham Lewis, Ben Nicholson, John Piper, Patrick Scott, Walter Sickert, Graham I Sutherland and John Tunnard. The number of exhibitions devoted to British art have included the comprehensive ' I one-man show of Henry Moore held in 1947. It contained both sculpture and drawings, many I lent from public and private collections in Great Britain. -

Download Our Guide To

BEST OF CORNWALL 2020 Marianne Stokes, née Priendlsberger 1855 - 1927 Lantern Light, 1888 Oil on canvas, 82.5 x 102 cm Penlee House Gallery & Museum Purchased by private treaty from Mr & Mrs Allan Amey with assistance from The Art Fund, The MLA/V&A Purchase Grant Fund and the Friends of Penlee A brief and incomplete history of ... art and artists in Cornwall By Andrea Breton Cornwall has always appealed to the creative type; a land of mists and megaliths, it combines a wide variety of landscape, from perfectly sanded coves to dramatic cliffs and breakers; bleak, haunted moors to lush vegetal valleys. There are picturesque harbours and grand country houses set in vast acreages. There are impressive landmarks from the past such as Tintagel Castle, St Michael’s Mount and more standing stones and Neolithic sites than you can shake a stick at. They exist happily alongside the present day futuristic domes of Eden, the stately grey bulk of Tate St Ives, old Mine chimneys (sensibly bestowed with World Heritage status) and the spoil heaps of the clay pits near St Austell. 35 BEST OF CORNWALL 2020 However there is more to Cornwall’s appeal than It was clear that luck landmarks. It is the geographical distance to the rest of was needed. Fortunately, the England; the quirk of geology which makes Cornwall Victorian age was coming somewhat longer than it is wide. Surrounded by the sea, and with it the age of steam it gives the county an all enveloping bright light, allegedly powered travel and the artists’ a couple of lux higher than the mainland. -

Elements of Innovators' Fame

Elements of Innovators’ Fame: Social Structure, Identity and Creativity Mitali Banerjee Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2017 © 2017 Mitali Banerjee All rights reserved Abstract Elements of Innovators’ Fame: Social Structure, Identity and Creativity Mitali Banerjee What makes an innovator famous? This is the principal question of this dissertation. I examine three potential drivers of the innovators’ fame – their social structure, creativity and identity. My empirical context is the early 20th century abstract artists in 1910-25. The period represents a paradigmatic shift in the history of modern art, the emergence of the abstract art movement. In chapter 2, I operationalize social structure by an innovator’s local peer network. I find that an innovator with structurally and compositionally diverse local network is likely to be more famous than the one with a homogenous local network. I find no statistical evidence for creativity as a link between social structure and fame. Instead, the evidence suggests that an innovator’s creative identity and access to promotional opportunities are the key drivers of her fame. In Chapter 3, I find that the creativity identity resulting from an innovator’s creative trajectory can lead to obscurity despite early fame and acclaim. The drastic change in the nature of a producer’s output can dilute her identity and cost her her niche. In combination with her peer network characteristics, these dynamics can mean obscurity even for talented and prolific innovators. In chapter 4, I undertake a large-scale analysis of the relationship between creativity and fame.