The 15 Most Corrupt Members of Congress Featuring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution List

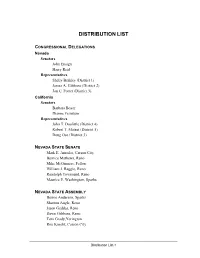

Revised DEIS/EIR Truckee River Operating Agreement DISTRIBUTION LIST CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATIONS Nevada Senators John Ensign Harry Reid Representatives Shelly Berkley (District 1) James A. Gibbons (District 2) Jon C. Porter (District 3) California Senators Barbara Boxer Dianne Feinstein Representatives John T. Doolittle (District 4) Robert T. Matsui (District 5) Doug Ose (District 3) NEVADA STATE SENATE Mark E. Amodei, Carson City Bernice Mathews, Reno Mike McGinness, Fallon William J. Raggio, Reno Randolph Townsend, Reno Maurice E. Washington, Sparks NEVADA STATE ASSEMBLY Bernie Anderson, Sparks Sharron Angle, Reno Jason Geddes, Reno Dawn Gibbons, Reno Tom Grady,Yerington Ron Knecht, Carson City Distribution List-1 Revised DEIS/EIR Truckee River Operating Agreement CALIFORNIA STATE SENATE Samuel Aanestad (District 4) Michael Machado (District 5) Thomas "Rico" Oller (District 1) Deborah Ortiz (District 6) CALIFORNIA STATE ASSEMBLY David Cox (District 5) Tim Leslie (District 4) Darrell Steinberg (District 9) FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCIES Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Washington, DC Army Corps of Engineers, Reno, NV Army Corps of Engineers, Washington, DC Army Corps of Engineers, Real Estate Division, Sacramento, CA Army Corps of Engineers, Planning Division, Sacramento, CA Bureau of Indian Affairs, Office of Trust and Economic Development, Washington, DC Bureau of Indian Affairs, Washington, DC Bureau of Indian Affairs, Western Regional Office, Phoenix, AZ Bureau of Land Management, Carson City District Office, Carson City, NV -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

TITLE FIRST LAST IAL 2016 LSTA 2016 STATE Rep. Don Young Y

IAL LSTA TITLE FIRST LAST 2016 2016 STATE Rep. Don Young Y Alaska Rep. Mike Rogers Y Alabama Rep. Terri Sewell Y Alabama Rep. Raul Grijalva Y Y Arizona Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick Y Arizona Rep. Martha McSally Y Arizona Rep. Kyrstan Sinema Y Arizona Rep. Xavier Becerra Y California Rep. Karen Bass California Rep. Julia Brownley Y Y California Rep. Lois Capps Y Y California Rep. Tony Cardenas Y Y California Rep. Judy Chu Y Y California Rep. Jim Costa Y California Rep. Susan Davis Y California Rep. Mark DeSaulinier Y Y California Rep. John Garamendi Y Y California California Rep. Janice Hahn Y California Rep. Jared Huffman Y California Rep. Barbara Lee Y California Rep. Zoe Lofgren Y California California Rep. Alan Lowenthal Y California Rep. Doris Matsui Y California California Rep. Kevin McCarthy California Rep. Jerry McNerney Y Y California California Rep. Grace Napolitano Y California California Rep. Scott Peters Y California Rep. Raul Ruiz California California Rep. Linda Sanchez Y California California Rep. Loretta Sanchez Y Y California California Rep. Adam Schiff Y Y California Rep. Brad Sherman California Rep. Jackie Speier Y California California Rep. Eric Swalwell Y California Rep. Mark Takano Y Y California Rep. Mike Thompson Y California Rep. Juan Vargas Y California California Rep. Maxine Waters Y Y California California Rep. Diana DeGette Y Y Colorado Rep. Jared Polis Y Colorado Colorado Rep. Joe Courtney Y Connecticut Rep. Elizabeth Esty Y Y Connecticut Connecticut Rep. Jim Himes Y Connecticut Rep. John Larson Y Connecticut Rep. John Carney Y Delaware Delegate Eleanor Norton Y Y District of Columbia Rep. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO U.S. Government Institutions and the Economy a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO U.S. Government Institutions and the Economy A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics by Grant Erik Johnson Committee in charge: Professor Julie Berry Cullen, Co-Chair Professor Valerie Ramey, Co-Chair Professor Jeffrey Clemens Professor Zoltan Hajnal Professor Thad Kousser 2018 Copyright Grant Erik Johnson, 2018 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Grant Erik Johnson is approved and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii DEDICATION To my parents, Kirk and Amy. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Dedication . iv Table of Contents . v List of Figures . vii List of Tables . ix Acknowledgements . xi Vita........................................................................ xiii Abstract of the Dissertation . xiv Chapter 1 Procuring Pork: Contract Characteristics and Channels of Influence . 1 1.1 Introduction . 2 1.2 Background . 7 1.3 Contract Concentration Index . 11 1.4 Data and Descriptive Statistics . 15 1.5 Empirical Framework . 17 1.6 Results . 19 1.6.1 Identification . 19 1.6.2 Baseline . 23 1.6.3 Own-Jursidiction vs. Other Procurement Spending . 24 1.7 Conclusion . 26 Chapter 2 Institutional Determinants of Municipal Fiscal Dynamics . 29 2.1 Introduction . 30 2.2 Background . 32 2.2.1 Municipal Governments . 32 2.2.2 Tax and Expenditure Limitations (TELs) . 35 2.3 Data................................................................ 37 2.3.1 Shock Construction . 37 2.3.2 Descriptive Statistics . 39 2.4 Empirical Strategy . 41 2.5 Results . 42 2.5.1 Main Results . -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 156 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, MAY 11, 2010 No. 70 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. and was NET REGULATION WILL HARM turned it over to the private sector and called to order by the Speaker. INVESTMENT AND INNOVATION lifted restrictions on its use by com- The SPEAKER pro tempore (Ms. mercial entities and the public. The f MARKEY of Colorado). The Chair recog- unregulated Internet is now starting to help spur a new technological revolu- MORNING-HOUR DEBATE nizes the gentleman from Florida (Mr. STEARNS) for 5 minutes. tion in this country. Where there were The SPEAKER. Pursuant to the Mr. STEARNS. Madam Speaker, a re- once separate phone, cable, wireless, order of the House of January 6, 2009, cent announcement by FCC Chairman and other industries providing distinct the Chair will now recognize Members Genachowski to impose new, burden- and separate services, we’re now seeing from lists submitted by the majority some regulation on the Internet and on a confluence and a blur of providers all and minority leaders for morning-hour Internet transmission appears to me to competing against each other for con- debate. be a political maneuver to regulate the sumers, offering broadband, voice, Internet. Several weeks ago, he indi- video services, and much more. f cated he was not going to push for net The Apple iPod is a perfect example of the confluence of the Internet, the FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY regulation. -

The Long Red Thread How Democratic Dominance Gave Way to Republican Advantage in Us House of Representatives Elections, 1964

THE LONG RED THREAD HOW DEMOCRATIC DOMINANCE GAVE WAY TO REPUBLICAN ADVANTAGE IN U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTIONS, 1964-2018 by Kyle Kondik A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Baltimore, Maryland September 2019 © 2019 Kyle Kondik All Rights Reserved Abstract This history of U.S. House elections from 1964-2018 examines how Democratic dominance in the House prior to 1994 gave way to a Republican advantage in the years following the GOP takeover. Nationalization, partisan realignment, and the reapportionment and redistricting of House seats all contributed to a House where Republicans do not necessarily always dominate, but in which they have had an edge more often than not. This work explores each House election cycle in the time period covered and also surveys academic and journalistic literature to identify key trends and takeaways from more than a half-century of U.S. House election results in the one person, one vote era. Advisor: Dorothea Wolfson Readers: Douglas Harris, Matt Laslo ii Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………....ii List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………..iv List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………..v Introduction: From Dark Blue to Light Red………………………………………………1 Data, Definitions, and Methodology………………………………………………………9 Chapter One: The Partisan Consequences of the Reapportionment Revolution in the United States House of Representatives, 1964-1974…………………………...…12 Chapter 2: The Roots of the Republican Revolution: -

Riverside County Candidate Statements

CANDIDATE STATEMENT FOR CANDIDATE STATEMENT FOR UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, 36TH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 36TH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT DR. RAUL RUIZ, Democratic PATRICE KIMBLER, Republican OCCUPATION: Emergency Doctor / Congressman EDUCATION AND QUALIFICATIONS: EDUCATION AND QUALIFICATIONS: Every day, our nation seems more divided by partisanship. Now more than My name is Patrice Kimbler. I am a wife, mother and grandmother with a ever, we need elected officials who put public service ahead of politics. passion to love and serve others. I’m not a career politician; I’m an emergency doctor who ran for Congress I’ve spent the last twenty years serving local communities as a volunteer to serve people. When patients came into my hospital, it didn’t matter for many charities, and was founder and director of a faith-based nonprofit. what political party they belonged to, whether they were wealthy, or who I’ve seen first-hand many of the challenges our local communities face. they knew. All that mattered was that we served people who needed us. Fed up with today’s political climate, I decided to take action. For far I brought that same commitment to Congress, serving people even while too long Californians have been subject to liberal policies by law makers Washington is gridlocked: that are ruining the great state of California. Out of control homelessness, sanctuary cities, the decriminalization/reduction of many crime, and out DELIVERING FOR VETERANS: I’ve helped 1,800 local veterans collect of control taxes are just some of the issues that we face. We have seen $6.6 million in benefits they were owed. -

Congressional Mail Logs for the President (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 8, folder “Congress - Congressional Mail Logs for the President (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. r Digitized from Box 8 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Presi dent's Mail - May 11, 1976 House 1. Augustus Hawkins Writes irr regard to his continuing · terest in meeting with the President to discuss the· tuation at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission prior to the appoint ment of a successor to Chairman owell W. Perry. 2. Larry Pressler Says he will vote to sustain e veto of the foreign military assistance se he believes the $3.2 billion should be u ed for nior citizens here at horne. 3. Gus Yatron Writes on behalf of Mrs. adys S. Margolis concerning the plight of Mr. Mi ail ozanevich and his family in the Soviet Union. 4. Guy Vander Jagt Endorses request of the TARs to meet with the President during their convention in June. -

June 7, 2006 the Honorable Alberto R. Gonzales Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington

June 7, 2006 The Honorable Alberto R. Gonzales Attorney General U.S. Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20530 Dear Attorney General Gonzales: Democracy 21 believes it is essential that you take all steps necessary to ensure that there is no political interference with the criminal investigations being conducted by the Public Integrity Section of the Justice Department and by U.S. Attorney offices in California concerning political corruption and potential criminal conduct by members of Congress. We strongly urge you to provide assurances to the public, and to the government prosecutors handling these cases, that you will not allow any political interference in these matters. These criminal investigations must be pursued wherever they lead, regardless of any political pressures that might be applied by members of Congress or others to influence the cases. Our concerns about possible political interference in these matters have only been heightened by the reactions of House Judiciary Committee Chairman James Sensenbrenner (R-WI) and other House leaders to the Justice Department’s obtaining of records from the congressional office of Representative William Jefferson (D-LA), pursuant to a court-approved search warrant. Regardless of the constitutional issues that may or may not be involved in the search of Representative Jefferson’s office, the overreactions of Chairman Sensenbrenner and other House members to the execution of a court-approved search warrant has raised concerns that enforcement officials are being warned to stay away from investigations involving members of Congress. This has occurred at a time, furthermore, when the Public Integrity Section’s investigation into the Jack Abramoff corruption scandals has reached a critical stage. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1. Defense Travel System (DTS) – #4373 2. DOD Travel Payments Improper Payment Measure – #4372 3. Follow up Amendment 4. DOD Earmarks Cost and Grading Amendment – #4370 5. Limitation on DoD Contract Performance Bonuses – #4371 1. Amendment # 4373 – No Federal funds for the future development and operation of the Defense Travel System Background The Defense Travel System (DTS) is an end-to-end electronic travel system intended to integrate all travel functions, from authorization through ticket purchase to accounting for the Department of Defense. The system was initiated in 1998 and it was supposed to be fully deployed by 2002. DTS is currently in the final phase of a six-year contract that expires September 30, 2006. In its entire history, the system has never met a deadline, never stayed within cost estimates, and never performed adequately. To date, DTS has cost the taxpayers $474 million – more than $200 million more than it was originally projected to cost. It is still not fully deployed. It is grossly underutilized. And tests have repeatedly shown that it does not consistently find the lowest applicable airfare – so even where it is deployed and used, it does not really achieve the savings proposed. This amendment prohibits continued funding of DTS and instead requires DOD to shift to a fixed price per transaction e-travel system used by government agencies in the civilian sector, as set up under General Services Administration (GSA) contracts. Quotes of Senators from last year’s debate • Senator Allen stated during the debate last year that “as a practical matter we would like to have another year or so to see (DTS) fully implemented.” • Senator Coleman stated during the debate, “… if we cannot get the right answers we should pull the plug, but now is not the time to pull the plug. -

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

16. County Executive/Legislation

OFFICE OF - COUNTY OF PLACER COUNN EXECUTIVE THOMAS M. MILLER, County Executive Officer BOARDMEMBERS F. C. 'ROCKY ROCKHOLM JIM HOLMES District 1 District 3 175 FULWEILER AVENUE I AUBURN, CALIFORNIA 95603 TELEPHONE: 5301889-4030 ROBERT M. WEYGANDT KIRK UHLER FAX: 5301889-4023 District 2 District 4 BRUCE KRANZ Dlstrict 5 To: The Honorable Board of Supervisors From: Thomas M. Miller, County Executive Officer By: Mary Herdegen, Senior Management Analyst 6 Date: January 23,2007 Subject: Support H.R. 17 - "Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Reauthorization Act of 2007" Action Reauested: Authorize the Board Chairman to sign a letter supporting House Resolution 17 - the "Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Reauthorization Act of 2007" that will extend the expired. act through Fiscal Year 2013. Additionally, authorize the Chairman to sign a letter to Congress to request the support of a one-year extension of the expired act in the Continuing Resolution that must be approved by February 15,2007. Background: The "Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000 (PL 106- 393)" expired December 3 1, 2006. This federal legislation established a six-year payment formula for counties, such as Placer, that receive revenue sharing payments for the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands. Based on historical timber receipts, the formula established a stable source of revenue to be used for education, county roads and various other county services and programs in rural areas. During this six-year period, the amount of this funding to Placer County totaled nearly $9.9 million.