WP7 Biswamoy Pati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXI NO. 5 DECEMBER - 2014 MADHUSUDAN PADHI, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary RANJIT KUMAR MOHANTY, O.A.S, ( SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Shrikshetra, Matha and its Impact Subhashree Mishra ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 India International Trade Fair - 2014 : An Overview Smita Kar ... 7 Mo Kahani' - The Memoir of Kunja Behari Dash : A Portrait Gallery of Pre-modern Rural Odisha Dr. Shruti Das ... 10 Protection of Fragile Ozone Layer of Earth Dr. Manas Ranjan Senapati ... 17 Child Labour : A Social Evil Dr. Bijoylaxmi Das ... 19 Reflections on Mahatma Gandhi's Life and Vision Dr. Brahmananda Satapathy ... 24 Christmas in Eternal Solitude Sonril Mohanty ... 27 Dr. B.R. Ambedkar : The Messiah of Downtrodden Rabindra Kumar Behuria ... 28 Untouchable - An Antediluvian Aspersion on Indian Social Stratification Dr. Narayan Panda ... 31 Kalinga, Kalinga and Kalinga Bijoyini Mohanty .. -

WP7 Biswamoy Pati

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Research Online Asia Research Centre Working Paper 7 IDENTITY, HEGEMONY, RESISTANCE: CONVERSIONS IN ORISSA, 1800-2000 Dr Biswamoy Pati 1 Identity, Hegemony, Resistance: Conversions in Orissa œ 1800-2000 IDENTITY, HEGEMONY, RESISTANCE: CONVERSIONS IN ORISSA, 1800-2000* The Problem: It is widely held that as far as Hinduism is considered, the concept of conversion does not exist. Traditionally, it is said that one cannot become a Hindu by conversion, since one has to be born a Hindu and indeed, innumerable tracts, articles and books have been written on the subject. 1 However, as this paper will attempt to show, the ground realities of social dynamics would appear to suggest something different and this premise (that one cannot become a Hindu) may, in a profound sense, be open to contest. One can cite here the history of the adivasi peoples and their absorption into brahminical Hinduism - a social process that would, in fact, point to the gaps and contradictions existing between this kind of traditional belief (in the impossibility of ”conversion‘ to Hinduism) and the complexities of actual cultural practice on the ground. In other words, this paper seeks to argue that the history of the indigenous peoples would instead seem to suggest that, in an important sense, Hinduism did ”convert‘, and the paper further goes on to raise the question whether adivasis and outcastes were/are Hindus in the first place. 2 ”Common-sense‘ dictates that this absence of a system of conversion within Hinduism makes it by implication, more humane, tolerant and perhaps superior to proselytising religions like Islam and Christianity. -

Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution In

Open Access Austin Journal of Forensic Science and Criminology Review Article Y-Chromosomal and Mitochondrial SNP Haplogroup Distribution in Indian Populations and its Significance in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) - A Review Based Molecular Approach Sinha M1*, Rao IA1 and Mitra M2 1Department of Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas Abstract University, India Disaster Victim Identification is an important aspect in mass disaster cases. 2School of Studies in Anthropology, Pt. Ravishankar In India, the scenario of disaster victim identification is very challenging unlike Shukla University, India any other developing countries due to lack of any organized government firm who *Corresponding author: Sinha M, Department of can make these challenging aspects an easier way to deal with. The objective Forensic Science, Guru Ghasidas University, India of this article is to bring spotlight on the potential and utility of uniparental DNA haplogroup databases in Disaster Victim Identification. Therefore, in this article Received: December 08, 2016; Accepted: January 19, we reviewed and presented the molecular studies on mitochondrial and Y- 2017; Published: January 24, 2017 chromosomal DNA haplogroup distribution in various ethnic populations from all over India that can be useful in framing a uniparental DNA haplogroup database on Indian population for Disaster Victim Identification (DVI). Keywords: Disaster Victim identification; Uniparental DNA; Haplogroup database; India Introduction with the necessity mentioned above which can reveal the fact that the human genome variation is not uniform. This inconsequential Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) is the recognized practice assertion put forward characteristics of a number of markers ranging whereby numerous individuals who have died as a result of a particular from its distribution in the genome, their power of discrimination event have their identity established through the use of scientifically and population restriction, to the sturdiness nature of markers to established procedures and methods [1]. -

Odisha As a Multicultural State: from Multiculturalism to Politics of Sub-Regionalism

Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences Volume VII, No II. Quarter II 2016 ISSN: 2229 – 5313 ODISHA AS A MULTICULTURAL STATE: FROM MULTICULTURALISM TO POLITICS OF SUB-REGIONALISM Artatrana Gochhayat Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Sree Chaitanya College, Habra, under West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal, India ABSTRACT The state of Odisha has been shaped by a unique geography, different cultural patterns from neighboring states, and a predominant Jagannath culture along with a number of castes, tribes, religions, languages and regional disparity which shows the multicultural nature of the state. But the regional disparities in terms of economic and political development pose a grave challenge to the state politics in Odisha. Thus, multiculturalism in Odisha can be defined as the territorial division of the state into different sub-regions and in terms of regionalism and sub- regional identity. The paper attempts to assess Odisha as a multicultural state by highlighting its cultural diversity and tries to establish the idea that multiculturalism is manifested in sub- regionalism. Bringing out the major areas of sub-regional disparity that lead to secessionist movement and the response of state government to it, the paper concludes with some suggestive measures. INTRODUCTION The concept of multiculturalism has attracted immense attention of the academicians as well as researchers in present times for the fact that it not only involves the question of citizenship, justice, recognition, identities and group differentiated rights of cultural disadvantaged minorities, it also offers solutions to the challenges arising from the diverse cultural groups. It endorses the idea of difference and heterogeneity which is manifested in the cultural diversity. -

EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY No. 647, CUTTACK, SATURDAY, APRIL 21, 2018 / BAISAKHA 1, 1940 HOME (ELECTIONS) DEPAR

EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 647, CUTTACK, SATURDAY, APRIL 21, 2018 / BAISAKHA 1, 1940 HOME (ELECTIONS) DEPARTMENT NOTIFICATION The 3rd April, 2018 No. 3154– VE(A)-61/2018 /Elec.– The following Notification, dated the 12th March, 2018 of Election Commission of India, New Delhi is hereby republished in the Extraordinary Gazette of Odisha for general information. Sd/- SURENDRA KUMAR Chief Electoral Officer, Odisha ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi-110001 Dated 12 th March,2018 21, Phalguna, 1939 (Saka) NOTIFICATION No. 82/ECI/LET/TERR/ES-II/OR-LA/ (20 & 17/2014)/2018: - In pursuance of Section 106 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (43 of 1951), the Election Commission hereby published the Order of the High Court of Orissa, dated 30.01.2018 passed in Election Petition No. 20 of 2014 (Sri Sahadev Xaxa -Vrs- Jogesh Kumar Singh & others) and Election Petition No. 17 of 2014 (Sri Ajay Kumar Patel Vrs Sri Jogesh Kumar Singh & others related to the 9-Sundargarh (ST) Assembly Constituency. 2 HIGH COURT OF ORISSA: CUTTACK ELPET NO.20 OF 2014 & ELPET NO.17 OF 2014 In the matter of an application under Section 80 to 84 read with Sections 100,101 of the Representation of People Act, 1951 read with Orissa High Court Rules to regulate proceedings under the' Representation of People Act.1951. ………………….. ELPET NO.20 OF 2014 Sahadev Xaxa …. ….. Petitioner Versus Jogesh K. Singh & Others … … Respondents For Petitioner : M/s. Gopal Agarwal, K. K. Mishra & T. Mishra For opp. Parties : Mr. Pitambar Acharya, Senior Advocate. ELPET NO.17 OF 2014 Ajay Ku. -

REJECTED LIST.Xlsx

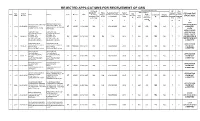

REJECTED APPLICATIONS FOR RECRUITMENT OF GRS Educational Qualification PHYSICAL ME HSC DISABILITY ( Photo Residentail Proof( Year of Intermediate/+2 passed Passed Appl. Date of 10th/ REASON FOR Sl No Name Address Caste Gender DOB Certificate Submitte He/She must belong Passing HSC Marks Computer(Y/ If Higher with Odia with Odia Sl.No Receipt Matric(Y/ Total submitted Y/N & d(Y/N) to Kalahandi) Exam secured N) Qualification Language Language REJECTION percentage N) Marks without 4th (Y/N) (Y/N) optional 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 10TH KESI MAJHI S/O- RAJA KESI MAJHI AT- JAMULI PO- CERTIFICATE NOT ,MAJHI AT- JAMULI PO- 1 2169 MOHANGIRI VIA- 26.04.2021 MOHANGIRI VIA- M.RAMPUR ST MALE 31.12.1999 NO Y KALAHANDI 2016 Y 600 250 YES NO Y Y SUBMIITED. M.RAMPUR PIN- 766102 PIN- 766103 GIVEN UNDERTAKING GOPINATH NAIK GOPINATH NAIK APPLICATION S/O-INDRAMANI NAIK S/O-INDRAMANI NAIK FORM , CASTE AT-PABLI, PO- AT-PABLI, PO- 2 1458 22.04.21 BADKARLAKOT BADKARLAKOT NA MALE 10.10.1993 NA NA NA 2012 Y 600 348 YES NO Y Y AND RESIDENCE VIA-JAIPATNA, DIST- VIA-JAIPATNA, DIST- CERTIFICATE NOT KALAHANDI, ODISHA KALAHANDI, ODISHA SUBMITTED PIN-766018, MOB- PIN-766018, MOB-6381221741 SUBHASMITA NAIK SUBHASMITA NAIK APPLICATION D/O-SANTOST KU NAYAK D/O-SANTOST KU NAYAK 3 656 13.04.21 AT/PO-NARLA AT/PO-NARLA OBC FEMALE 03.07.2000 NO Y KALAHANDI 2015 Y 600 327 YES BA Y Y FORM NOT PIN-766100, MOB-766100 PIN-766100, MOB-766100 SUBMITTED AMULYA MAJHI AMULYA MAJHI S/O-HARU MAJHI S/O-HARU MAJHI APPLICATION AT-GODRAMASKA,PO- AT-GODRAMASKA,PO- 4 740 13.04.21 BIRIKOT -

Annexure V - Caste Codes State Wise List of Castes

ANNEXURE V - CASTE CODES STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE TAMIL NADU CODE CASTE 1 ADDI DIRVISA 2 AKAMOW DOOR 3 AMBACAM 4 AMBALAM 5 AMBALM 6 ASARI 7 ASARI 8 ASOOY 9 ASRAI 10 B.C. 11 BARBER/NAI 12 CHEETAMDR 13 CHELTIAN 14 CHETIAR 15 CHETTIAR 16 CRISTAN 17 DADA ACHI 18 DEYAR 19 DHOBY 20 DILAI 21 F.C. 22 GOMOLU 23 GOUNDEL 24 HARIAGENS 25 IYAR 26 KADAMBRAM 27 KALLAR 28 KAMALAR 29 KANDYADR 30 KIRISHMAM VAHAJ 31 KONAR 32 KONAVAR 33 M.B.C. 34 MANIGAICR 35 MOOPPAR 36 MUDDIM 37 MUNALIAR 38 MUSLIM/SAYD 39 NADAR 40 NAIDU 41 NANDA 42 NAVEETHM 43 NAYAR 44 OTHEI 45 PADAIACHI 46 PADAYCHI 47 PAINGAM 48 PALLAI 49 PANTARAM 50 PARAIYAR 51 PARMYIAR 52 PILLAI 53 PILLAIMOR 54 POLLAR 55 PR/SC 56 REDDY 57 S.C. 58 SACHIYAR 59 SC/PL 60 SCHEDULE CASTE 61 SCHTLEAR 62 SERVA 63 SOWRSTRA 64 ST 65 THEVAR 66 THEVAR 67 TSHIMA MIAR 68 UMBLAR 69 VALLALAM 70 VAN NAIR 71 VELALAR 72 VELLAR 73 YADEV 1 STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE MADHYA PRADESH CODE CASTE 1 ADIWARI 2 AHIR 3 ANJARI 4 BABA 5 BADAI (KHATI, CARPENTER) 6 BAMAM 7 BANGALI 8 BANIA 9 BANJARA 10 BANJI 11 BASADE 12 BASOD 13 BHAINA 14 BHARUD 15 BHIL 16 BHUNJWA 17 BRAHMIN 18 CHAMAN 19 CHAWHAN 20 CHIPA 21 DARJI (TAILOR) 22 DHANVAR 23 DHIMER 24 DHOBI 25 DHOBI (WASHERMAN) 26 GADA 27 GADARIA 28 GAHATRA 29 GARA 30 GOAD 31 GUJAR 32 GUPTA 33 GUVATI 34 HARJAN 35 JAIN 36 JAISWAL 37 JASODI 38 JHHIMMER 39 JULAHA 40 KACHHI 41 KAHAR 42 KAHI 43 KALAR 44 KALI 45 KALRA 46 KANOJIA 47 KATNATAM 48 KEWAMKAT 49 KEWET 50 KOL 51 KSHTRIYA 52 KUMBHI 53 KUMHAR (POTTER) 54 KUMRAWAT 55 KUNVAL 56 KURMA 57 KURMI 58 KUSHWAHA 59 LODHI 60 LULAR 61 MAJHE -

ANSWERED ON:25.07.2016 Inclusion in ST List Gopal Dr

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA TRIBAL AFFAIRS LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO:119 ANSWERED ON:25.07.2016 Inclusion in ST List Gopal Dr. K.;Majhi Shri Balabhadra Will the Minister of TRIBAL AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) The criteria and procedure being followed for inclusion/exclusion from and for carrying out other modifications in Scheduled Tribes (ST) List; (b) whether the Government has received proposals from various State Governments including Odisha for inclusion of various communities in the list of STs, and if so, the details thereof; (c) the action taken by the Government thereon along with the names of communities included in the list of STs during the last three years and the current year, State/UT-wise; (d) whether a number of proposals including those from Odisha for inclusion of tribes in the list of Scheduled Tribes are still pending with the Government for approval; and (e) if so, the details thereof and the reasons therefore along with the present status thereof and the time by which these proposals are likely to be approved, State/UT-wise? Answer MINISTER OF TRIBAL AFFAIRS (SHRI JUAL ORAM) (a) to (e) : A statement is laid on the table of the House. **** STATEMENT IN REFERENCE TO LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO. 119 FOR 25-7-2016 REGARDING INCLUSION IN ST LIST BY SHRI BALABHADRA MAJHI AND DR. K. GOPAL. (a)Criteria followed for specification of a community as a Scheduled Tribe (ST) are: (i) indications of primitive traits, (ii) distinctive culture, (iii) geographical isolation, (iv) shyness of contact with the community at large, and (v) backwardness. -

Social Anthropology of Orissa: a Critique

International Journal of Cross-Cultural Studies Vol. 2 No. 1 (June, 2016) ISSN: 0975-1173 www.mukpublications.com Social Anthropology of Orissa: A Critique Nava Kishor Das Anthropological Survey of India India ABSTRACT Orissa is meeting place of three cultures, Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, and Munda and three ethno- linguistic sections. There are both indigenous and immigrant components of the Brahmans, Karna, who resemble like the Khatriyas, and others. The theory that Orissa did not have a viable Kshatriya varna has been critically considered by the historian -anthropologists. We will also see endogenous and exogenous processes of state formation. The Tribespeople had generally a two-tier structure of authority- village chief level and at the cluster of villages (pidha). Third tier of authority was raja in some places. Brahminism remained a major religion of Orissa throughout ages, though Jainism and Buddhism had their periods of ascendancy. There is evidence when Buddhism showed tendencies to merge into Hinduism, particularly into Saivism and Saktism. Buddhism did not completely die out, its elements entered into the Brahmanical sects. The historians see Hinduisation process intimately associated with the process of conversion, associated with the expansion of the Jagannatha cult, which co-existed with many traditions, and which led to building of Hindu temples in parts of tribal western Orissa. We notice the co-existence of Hinduisation/ peasantisation/ Kshatriyaisation/ Oriyaisation, all operating variously through colonisation. In Orissa, according to Kulke it was continuous process of ‘assimilation’ and partial integration. The tribe -Hindu caste intermingling is epitomised in the Jagannatha worship, which is today at the centre of Brahminic ritual and culture, even though the regional tradition of Orissa remaining tribal in origin. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1Introduction 1. Phakirmohana Senapati, Atma-Jivana-Carita (My Times and I), Translated by John Boulton, (Bhubaneswar: Orissa Sahitya Akademi, [1917], 1985) pp 28–9. 2. Senapati, Atma-Jivana Carita, p 29. 3. Poverty is an indeterminate term that has many distinct meanings (See, for example, B. Baulch (ed.), ‘Editorial: the New Poverty Agenda: a Disputed Consensus’, in IDS Bulletin, 27, 1, 1996, p 2 and other articles in this special issue on Poverty, Policy and Aid). The same is true for hunger. The concept of ‘poverty’ is commonly used in association with terms such as ‘insecurity’, ‘vulnerability’, ‘destitution’, ‘incapacity’, ‘powerlessness’, and ‘ill-being’, to imply constraints on a person’s ability to act or to fulfill their aims or goals (see Chapter 2 and 3 of this volume). Hunger engenders similar images of ‘incapacity’ and ‘insecurity’ through limitations on one’s ability to act created by one’s limited access to a suitable quantity and balance of nutri- ents. In India, poverty is defined by the Planning Commission in terms of a nutrtional baseline measured in calories (the ‘food energy method’). The Planning Commission defines India’s ‘poverty line’ to be a per capita monthly expenditure of Rs49 for rural areas and Rs57 in urban areas at 1973–4 all-India prices; corresponding to a total household per capita expenditure sufficient to provide a daily intake of 2 400 calories per person in rural areas and 2 100 in urban areas in addition to basic non-food items (e.g. clothing, transport). See further in World Bank, India: Achievements and Challenges in Reducing Poverty: a World Bank Country Study (Washington DC: World Bank, 1997), p 3ff. -

Name Capital Salute Type Existed Location/ Successor State Ajaigarh State Ajaygarh (Ajaigarh) 11-Gun Salute State 1765–1949 In

Location/ Name Capital Salute type Existed Successor state Ajaygarh Ajaigarh State 11-gun salute state 1765–1949 India (Ajaigarh) Akkalkot State Ak(k)alkot non-salute state 1708–1948 India Alipura State non-salute state 1757–1950 India Alirajpur State (Ali)Rajpur 11-gun salute state 1437–1948 India Alwar State 15-gun salute state 1296–1949 India Darband/ Summer 18th century– Amb (Tanawal) non-salute state Pakistan capital: Shergarh 1969 Ambliara State non-salute state 1619–1943 India Athgarh non-salute state 1178–1949 India Athmallik State non-salute state 1874–1948 India Aundh (District - Aundh State non-salute state 1699–1948 India Satara) Babariawad non-salute state India Baghal State non-salute state c.1643–1948 India Baghat non-salute state c.1500–1948 India Bahawalpur_(princely_stat Bahawalpur 17-gun salute state 1802–1955 Pakistan e) Balasinor State 9-gun salute state 1758–1948 India Ballabhgarh non-salute, annexed British 1710–1867 India Bamra non-salute state 1545–1948 India Banganapalle State 9-gun salute state 1665–1948 India Bansda State 9-gun salute state 1781–1948 India Banswara State 15-gun salute state 1527–1949 India Bantva Manavadar non-salute state 1733–1947 India Baoni State 11-gun salute state 1784–1948 India Baraundha 9-gun salute state 1549–1950 India Baria State 9-gun salute state 1524–1948 India Baroda State Baroda 21-gun salute state 1721–1949 India Barwani Barwani State (Sidhanagar 11-gun salute state 836–1948 India c.1640) Bashahr non-salute state 1412–1948 India Basoda State non-salute state 1753–1947 India -

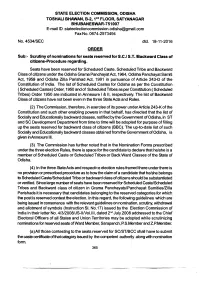

ORDER Sub:- Scrutiny of Nominations for Seats Reserved for SC

STATE ELECTION COMMISSION, ODISHA TOSHALIBHAWAN, B-2,1ST FLOOR, SATYANAGAR BHUBANESWAR-751007 E-mail ID :[email protected] Fax No. 0674-2573494 No. 4534/SEC dtd. 18-11-2016 ORDER Sub:- Scrutiny of nominations for seats reserved for S.C./ S.T. /Backward Class of citizens-Procedure regarding. Seats have been reserved for Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe and Backward Class of citizens under the Odisha Grama Panchayat Act, 1964, Odisha Panchayat Samiti Act, 1959 and Odisha Zilla Parishad Act, 1991 in pursuance of Article 243-D of the Constitution of India. The list of Scheduled Castes for Odisha as per the Constitution ( Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950 and of Scheduled Tribes as per Constitution ( Scheduled Tribes) Order 1950 are indicated in Annexure I & II, respectively. The list of Backward Class of citizens have not been even in the three State Acte and Rules. (2) The Commission, therefore, in exercise of its power under Article 243-K of the Constitution and such other enabling powers in that behalf, has directed that the list of Socially and Educationally backward classes, notified by the Government of Odisha, in ST and SC Development Department from time to time will be adopted for purpose of filling up the seats reserved for backward class of citizens (BBC). The up-to-date list of such Socially and Educationally backward classes obtai ned from the Government of Odisha, is given inAnnexure III. (3) The Commission has further noted that in the Nomination Forms prescribed under the three election Rules, there is space for the candidate to declare that he/she is a member of Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribes or Back Ward Classes of the State of Odisha.