North Korea's SA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

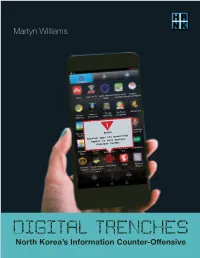

Digital Trenches

Martyn Williams H R N K Attack Mirae Wi-Fi Family Medicine Healthy Food Korean Basics Handbook Medicinal Recipes Picture Memory I Can Be My Travel Weather 2.0 Matching Competition Gifted Too Companion ! Agricultural Stone Magnolia Escpe from Mount Baekdu Weather Remover ERRORTelevision the Labyrinth Series 1.25 Foreign apps not permitted. Report to your nearest inminban leader. Business Number Practical App Store E-Bookstore Apps Tower Beauty Skills 2.0 Chosun Great Chosun Global News KCNA Battle of Cuisine Dictionary of Wisdom Terms DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive DIGITAL TRENCHES North Korea’s Information Counter-Offensive Copyright © 2019 Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior permission of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1001 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 435 Washington, DC 20036 P: (202) 499-7970 www.hrnk.org Print ISBN: 978-0-9995358-7-5 Digital ISBN: 978-0-9995358-8-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019919723 Cover translations by Julie Kim, HRNK Research Intern. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Gordon Flake, Co-Chair Katrina Lantos Swett, Co-Chair John Despres, -

North Korea: U.S. Relations, Nuclear Diplomacy, and Internal Situation Emma Chanlett-Avery, Coordinator Specialist in Asian Affairs

North Korea: U.S. Relations, Nuclear Diplomacy, and Internal Situation Emma Chanlett-Avery, Coordinator Specialist in Asian Affairs Ian E. Rinehart Analyst in Asian Affairs Mary Beth D. Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation January 15, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41259 Summary North Korea has presented one of the most vexing and persistent problems in U.S. foreign policy in the post-Cold War period. The United States has never had formal diplomatic relations with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (the official name for North Korea), although since 2000 contact at a lower level has ebbed and flowed. Negotiations over North Korea’s nuclear weapons program have occupied the past three U.S. administrations, even as some analysts anticipated a collapse of the isolated authoritarian regime. North Korea has been the recipient of over $1 billion in U.S. aid (though none since 2009) and the target of dozens of U.S. sanctions. Negotiations over North Korea’s nuclear weapons program began in the early 1990s under the Clinton Administration. As U.S. policy toward Pyongyang evolved through the 2000s, the negotiations moved from a bilateral format to the multilateral Six-Party Talks (made up of China, Japan, Russia, North Korea, South Korea, and the United States). Although the talks reached some key agreements that laid out deals for aid and recognition to North Korea in exchange for denuclearization, major problems with implementation persisted. The talks have been suspended throughout the Obama Administration. As diplomacy remains stalled, North Korea continues to develop its nuclear and missile programs in the absence of any agreement it considers binding. -

North Korean Strategic Strategy: Combining Conventional Warfare with The

NORTH KOREAN STRATEGIC STRATEGY: COMBINING CONVENTIONAL WARFARE WITH THE ASYMMETRICAL EFFECTS OF CYBER WARFARE By Jennifer J. Erlendson A Capstone Project Submitted to the Faculty of Utica College March, 2013 In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Science – Cybersecurity – Intelligence and Forensics © Copyright 2013 by Jennifer J. Erlendson All Rights Reserved ii Abstract Emerging technologies play a huge role in security imbalances between nation states. Therefore, combining the asymmetrical effects of cyberattacks with conventional warfare can be a force multiplier; targeting critical infrastructure, public services, and communication systems. Cyber warfare is a relatively inexpensive capability which can even the playing field between nations. Because of the difficulty of assessing attribution, it provides plausible deniability for the attacker. Kim Jong Il (KJI) studied the 2003 Gulf War operational successes of the United States (U.S.) and the United Kingdom (U.K.), noting the importance of high-tech weapons and information superiority. KJI realized the only way to compete with the U.S.’technology and information superiority was through asymmetric warfare. During the years that followed, the U.S. continued to strengthen its conventional warfare capabilities and expand its technological dominance, while North Korea (NK) sought an asymmetrical advantage. KJI identified the U.S.’ reliance on information technology as a weakness and determined it could be countered through cyber warfare. Since that time, there have been reports indicating a NK cyber force of 300-3000 soldiers; some of which may be operating out of China. Very little is known about their education, training, or sophistication; however, the Republic of Korea (ROK) has accused NK of carrying out cyber-attacks against the ROK and the U.S since 2004. -

CELL PHONES in NORTH KOREA Has North Korea Entered the Telecommunications Revolution?

CELL PHONES IN NORTH KOREA Has North Korea Entered the Telecommunications Revolution? Yonho Kim ABOUT THE AUTHOR Yonho Kim is a Staff Reporter for Voice of America’s Korea Service where he covers the North Korean economy, North Korea’s illicit activities, and economic sanctions against North Korea. He has been with VOA since 2008, covering a number of important developments in both US-DPRK and US-ROK relations. He has received a “Superior Accomplishment Award,” from the East Asia Pacific Division Director of the VOA. Prior to joining VOA, Mr. Kim was a broadcaster for Radio Free Asia’s Korea Service, focused on developments in and around North Korea and US-ROK alliance issues. He has also served as a columnist for The Pressian, reporting on developments on the Korean peninsula. From 2001-03, Mr. Kim was the Assistant Director of The Atlantic Council’s Program on Korea in Transition, where he conducted in-depth research on South Korean domestic politics and oversaw program outreach to US government and media interested in foreign policy. Mr. Kim has worked for Intellibridge Corporation as a freelance consultant and for the Hyundai Oil Refinery Co. Ltd. as a Foreign Exchange Dealer. From 1995-98, he was a researcher at the Hyundai Economic Research Institute in Seoul, focused on the international economy and foreign investment strategies. Mr. Kim holds a B.A. and M.A. in International Relations from Seoul National University and an M.A. in International Relations and International Economics from the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. -

North Korean Leadership Dynamics and Decision-Making Under Kim Jong-Un a Second Year Assessment

North Korean Leadership Dynamics and Decision-making under Kim Jong-un A Second Year Assessment Ken E. Gause Cleared for public release COP-2014-U-006988-Final March 2014 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the glob- al community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “prob- lem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the follow- ing areas: The full range of Asian security issues The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf Maritime strategy Insurgency and stabilization Future national security environment and forces European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea Latin America The world’s most important navies Deterrence, arms control, missile defense and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

Discrepant Kisses: the Reception and Remediation of North Korean Children’S Performances Circulated on Social Media

Discrepant Kisses: The Reception and Remediation of North Korean Children’s Performances Circulated on Social Media DONNA LEE KWON Abstract This article explores the burgeoning realm of videos uploaded on YouTube generated from content produced in North Korea otherwise known as the DPRK (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea). Through state-sanctioned and individual channels, thousands of videos of North Korean music and dance have been uploaded, some resulting in over 57 million hits on YouTube. Taking a cue from this fascination, I employ digital ethnography to investigate the online reception and remediation of North Korean children’s performances alongside their online comments on YouTube. I also draw from fieldwork conducted in North Korea in 2007. Theories that espouse the democratic participatory effects of social media platforms do not apply in North Korea where most of the uploaded material is produced and controlled by the state. Given this, I argue that North Korea’s engagement with social media is marked by a profound disjuncture where the majority of videos portray ideological North Korean subjects in an online context where very few North Korean citizens are able to engage with this material as social media. I analyze how this disjuncture plays out as international users respond to and remediate these videos in various ways or by creating mash-ups that subvert their original ideological content. A young North Korean girl in a red, babydoll dress sings a song called “Kiss” (Ppo-ppo) [figure 1].1 Another girl, this time in white, extolls the virtues of the “King Potato” (Wang Kamja). Five North Korean boys and girls—noticeably dwarfed by their guitars—perform a song called “Our Kindergarten Teacher” (Yuch’iwŏn uri sŏnsaengnim) garnering over 57 million views on YouTube.2 All three of these memorable children’s performances have become subject to intense online reception and have generated various creative and discrepant remediations. -

Master's Degree Programme – Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004) in Comparative International Relations at Ca' Foscari Universi

1 Master’s Degree programme – Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004) In Comparative International Relations At Ca’ Foscari University of Venice Final Thesis THE TELECOMMUNICATION SYSTEM IN NORTH KOREA Supervisor Ch. Prof. Rosa Caroli Asst. Prof. Vincenza D’urso Graduand Paolo Pedrini Matriculation Number 827084 Academic Year 2015/2016 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduzione in lingua italiana INTRODUCTION 1. CHAPTER ONE 1.1. Introduction 1.2. North Korea’s mobile communication history in a nutshell 1.3. Why Orascom? 1.3.1. A silent divorce? 1.4. Domestic cellphone: Get involved! 1.5. Rate plans and top-up cards 1.6. Handsets and gizmos 1.7. What about foreigners? 1.8. Conclusions 2. CHAPTER TWO 2.1. Introduction 2.2. Black market breakdown 2.3. Deal with it! 2.4. Salaries in North Korea? 2.5. Smuggling into North Korea 2.6. The Jangmadang and grasshopper merchants 2.7. Making connection 2.7.1. Brokers 2.7.2. Calling the South 2.7.3. The surveillance 2.7.4. What happen if you get caught? 2.8. Conclusions 3 INTRODUZIONE IN LINGUA ITALIANA: Quando sfogliamo le notizie di cronaca, ci capita ciclicamente di leggere articoli sulla Corea del Nord: le follie legate al giovane dittatore Kim, i campi di prigionia, le minacce dei missili atomici e via dicendo. Ciò che invece non giunge attraverso i media è una chiara figura in grado di descrivere come realmente vivono i Nord Coreani, i vari strati che compongono la loro società, il loro stile di vita e le diverse attività che caratterizzano la loro quotidianità. -

North Korean Leadership Dynamics and Decision-Making Under Kim Jong-Un a First Year Assessment

North Korean Leadership Dynamics and Decision-making under Kim Jong-un A First Year Assessment Ken E. Gause Cleared for public release COP-2013-U-005684-Final September 2013 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the glob- al community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “prob- lem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the follow- ing areas: The full range of Asian security issues The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf Maritime strategy Insurgency and stabilization Future national security environment and forces European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea Latin America The world’s most important navies Deterrence, arms control, missile defense and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

Connection Denied

CONNECTION DENIED RESTRICTIONS ON MOBILE PHONES AND OUTSIDE INFORMATION IN NORTH KOREA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Cover photo: A woman talks on a mobile phone at the Monument Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under to Party Founding in the capital, Pyongyang. 11 October 2015. a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international © ED JONES/AFP/Getty Images 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 24/3373/2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................. 5 Methodology ................................................................................................................ -

Death and Transfiguration: the Late Kim Jong-Il Aesthetic in North Korean Cultural Production

This is a repository copy of Death and Transfiguration: The Late Kim Jong-il Aesthetic in North Korean Cultural Production. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/95973/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Cathcart, AJ and Korhonen, P (2017) Death and Transfiguration: The Late Kim Jong-il Aesthetic in North Korean Cultural Production. Popular Music and Society, 40 (4). pp. 390-405. ISSN 0300-7766 https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2016.1158987 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Death and Transfiguration: The Late Kim Jong-il Aesthetic in North Korean Cultural Production By Adam Cathcart and Pekka Korhonen Adam Cathcart [[email protected]] Lecturer in Chinese -

Compromising Connectivity Information Dynamics Between the State and Society in a Digitizing North Korea

compromising connectivity information dynamics between the state and society in a digitizing north korea nat kretchun catherine lee seamus tuohy table of contents 1 the continuing evolution of the north korean information environment 4 general media environment 4 sources of information 6 media and communications devices 8 traditional broadcast media 8 television 9 radio 17 digital media 17 content 18 non-networked systems 18 devices 24 government control of media in the kim jong un era 25 bribery 26 the bureaucratic specialization of media control 27 group 118 27 group 109 29 official content 32 mobile phones 32 legal mobile phones in north korea 34 profiles of mobile phone users 38 mobile phones as communication devices 40 mobile phones as media devices InterMedia 44 mobile software–based censorship and the signature system 47 broader mobile phone censorship and surveillance mechanisms 50 software-based censorship and surveillance beyond mobile devices 50 automated censorship 51 tamper resistance 52 surveillance and tracking mechanisms 53 contradictions in digital censorship and surveillance efforts 55 digitally networked spaces 55 intranet and internet 55 development of the internet in north korea 56 general population: the north korean intranet 56 elite access: internet beyond the intranet, albeit limited 58 hyper elite access: full unbridled internet 58 regime’s internet strategy going forward 60 connections to the outside world: chinese mobile phones and cross-border business 60 chinese mobile phones 62 defector links 64 person-to-person -

North Korea's Cultural Diplomacy in the Early Kim Jong-Un

North Korea’s Cultural Diplomacy in the Early Kim Jong-un Era Adam Cathcart and Steven Denney Structured Abstract Article type: research paper Purpose—This article describes and analyzes the DPRK’s cultural diplomacy during the early months of Kim Jong-un’s reign. Methodology—We analyze the recent practice of North Korea’s cultural diplo- macy, using two case studies: the KCNA–Associated Press photo exhibition in New York, and the tour of the Unhasu Orchestra to Paris. Findings—Both initiatives coincided with the first months of Kim Jong-un’s reign, and can provide an alternate perspective on both North Korean foreign pol- icy and the wider debate about how to best engage the DPRK. Originality/value—The article thus adds to the literature on North Korean for- eign relations as well as cultural diplomacy more generally. Keywords: Associated Press, Kim Jong-un, Korean Central News Agency, North Korean cultural diplomacy, North Korean foreign relations, public diplomacy, soft power, Unhasu Orchestra Adam Cathcart, School of History, University of Leeds, West Yorkshire, LS2 9JT, United Kingdom; Office: +(44) 0113-34-35585; [email protected] Steven Denney, University of Toronto, 100 St. George Street, Sidney Smith Hall, Room 3018, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3G3; [email protected]. ca North Korean Review / DOI: 10.3172/NKR.9.2.29 / Volume 9, Number 2 / Fall 2013 / pp. 29–42 / ISSN 1551-2789 (Print) / ISSN 1941-2886 (Online) / © 2013 McFarland & Company, Inc. North Korea’s Cultural Diplomacy in the Early Kim Jong-un Era 29 Introduction Since the accession to power of Kim Jong-un, the North Korean state has lost no time in establishing the appearance of an accelerated internationalization.1 One important element in this process has been what is, by North Korea’s own closed stan- dards, a rather vigorous program of cultural diplomacy.