Saudi Arabia: Terrorist Financing Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Origination, Organization, and Prevention: Saudi Arabia, Terrorist Financing and the War on Terror”

Testimony of Steven Emerson with Jonathan Levin Before the United States Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs “Terrorism Financing: Origination, Organization, and Prevention: Saudi Arabia, Terrorist Financing and the War on Terror” July 31, 2003 Steven Emerson Executive Director The Investigative Project 5505 Conn. Ave NW #341 Washington DC 20015 Email: [email protected] phone 202-363-8602 fax 202 966 5191 Introduction Terrorism depends upon the presence of three primary ingredients: Indoctrination, recruitment and financing. Take away any one of those three ingredients and the chances for success are geometrically reduced. In the nearly two years since the horrific attacks of 9/11, the war on terrorism has been assiduously fought by the US military, intelligence and law enforcement. Besides destroying the base that Al Qaeda used in Afghanistan, the United States has conducted a comprehensive campaign in the United States to arrest, prosecute, deport or jail those suspected of being connected to terrorist cells. The successful prosecution of terrorist cells in Detroit and Buffalo and the announcement of indictments against suspected terrorist cells in Portland, Seattle, northern Virginia, Chicago, Tampa, Brooklyn, and elsewhere have demonstrated the resolve of those on the front line in the battle against terrorism. Dozens of groups, financial conduits and financiers have seen their assets frozen or have been classified as terrorist by the US Government. One of the most sensitive areas of investigation remains the role played by financial entities and non-governmental organizations (ngo’s) connected to or operating under the aegis of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Since the July 24 release of the “Report of the Joint Inquiry into the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001,” the question of what role Saudi Arabia has played in supporting terrorism, particularly Al Qaeda and the 9/11 attacks, has come under increasing scrutiny. -

Allies, Adversaries & Enemies

Allies, Adversaries & Enemies: AMERICA’S INCREASINGLY COMPLEX ALLIANCES A DIVISION OF THE FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES WASHINGTON, D.C. Copyright © 2014 by FDD Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Edition For more information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to: [email protected], or Permissions, FDD Press, P.O. Box 33249, Washington, D.C. 20033 ISBN: 978-0981971278 Cover design: Beth Singer Design / www.bethsingerdesign.com Publication design: Basis / www.basisbranding.com Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 When U.S. Allies Are Also Adversaries and Enemies: A Growing Trend ........................................................................... 1 Jonathan Schanzer and Daveed Gartenstein-Ross PAKISTAN CHAPTER 2 A Handcuffed Superpower: The U.S., Pakistan, and the Afghanistan War ......................................................................... 13 Daveed Gartenstein-Ross CHAPTER 3 Pakistan’s Proxies, Al-Qaeda’s Allies .......................................... 21 Thomas Joscelyn CHAPTER 4 Back to the Future: The Return to a Pre-9/11 World in Pakistan and Afghanistan .......................................................................... 33 Reuel Marc Gerecht SAUDI ARABIA CHAPTER 5 Sources of American Frustration with Saudi Arabia ................ 43 David Andrew Weinberg CHAPTER 6 The Sequel: How the Saudis are Letting the -

Download the Publication

Viewpoints No. 102 Saudi Arabia Faces the Missing 28 Pages David B. Ottaway Middle East Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Center May 2016 The question of possible Saudi links to the 9/11 hijackers has haunted and soured relations between the United States and Saudi Arabia for 15 years. Now the probable release of 28 classified pages from a congressional probe plus pressure from Congress to strip the Saudi government of its sovereign immunity to allow 9/11 families to sue the kingdom in U.S. courts are forcing yet another examination of the Saudi role in the worst act of terrorism ever perpetuated on American soil. Middle East Program ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ In December 2002, a joint Senate-House intelligence committee published its findings on the horrendous 9/11 terrorist attacks, which included evidence of possible links between the government of Saudi Arabia and some of the 15 Saudis involved in the bombings of the Pentagon and Twin Towers that cost nearly 3,000 American lives. For national security reasons, the 28 pages detailing that information were never published. But they may be shortly and revive yet another intense examination of alleged Saudi support for anti-American terrorism. The famous missing pages, if now declassified, will likely put the former Saudi ambassador to Washington, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, and his wife, Haifa, back in the limelight. Some of the allegations after the attacks focused on the royal couple’s financial aid to the Saudi spouse of a student who appeared to have had contacts with two of the hijackers living in California, Nawaf al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Mihdhar, prior to 9/11. -

The Globalization of Terror Funding

THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 74 The Globalization of Terror Funding Gil Feiler © The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, 52900, Israel http://www.besacenter.org ISSN 0793-1042 September 2007 The Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies The BESA Center for Strategic Studies at Bar-Ilan University was founded by Dr. Thomas O. Hecht, a Canadian Jewish community leader. The Center is dedicated to the memory of Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, who concluded the first Arab-Israel peace agreement. The Center, a non-partisan and independent institute, seeks to contribute to the advancement of Middle East peace and security by conducting policy-relevant research on strategic subjects, particularly as they relate to the national security and foreign policy of Israel. Mideast Security and Policy Studies serve as a forum for publication or re-publication of research conducted by BESA associates. Publication of a work by BESA signifies that it is deemed worthy of public consideration but does not imply endorsement of the author's views or conclusions. BESA Colloquia on Strategy and Diplomacy summarize the papers delivered at conferences and seminars held by the Center, for the academic, military, official and general publics. In sponsoring these discussions, the BESA Center aims to stimulate public debate on, and consideration of, contending approaches to problems of peace and war in the Middle East. A listing of recent BESA publications can be found at the end of this booklet. -

The Miscreants' Global Bust-Out: Preface | Deep Capture

4/12/2019 The Miscreants' Global Bust-Out: Preface | Deep Capture Home About Enter your search keywords Story of Deep Capture Michael Milken and Dendreon The Movie Mitchell Report AntiSocialMedia Data Archive Podcast Categorized | Featured Stories, The Deep Capture Campaign The Miscreants’ Global Bust-Out: Preface Posted on 28 April 2011 by Patrick Byrne “A bust-out is a scheme customarily employed by organized crime to deplete the assets of a legit imate business, thus forcing it into bankruptcy.” State of New Jersey Commission of Investigation 1988 Report, “Subversion By Organized Crime And Other Unscrupulous Elements of the Check Cashing Industry” “BUSTOUT: a confidence scheme in which an established business is taken over, a large stock of merchandise is purchased on credit and quickly sold, and the business is then abandoned or bankruptcy is declared.” – Merriam-Webster Dictionary Mark Mitchell has continued exploring the financial instability of the last four years, including the crash of 2008 and the Flash Crash of 2010. His conclusion is that various activities associated with market manipulation (e.g., naked short selling, high frequency trading, derivatives such as Credit Default Swaps and synthetic CDOs, sponsored access, regulatory capture, press manipulation) follow a familiar leverage-and-loot pattern and can be traced to a fairly cohesive network that includes Italian and Russian organized crime, Sunni extremist financiers with ties to Al Qaeda, the Russian FSB, the Albanian Mafia, agents of the Iranian regime, and close associates of Michael Milken. The result, “The Miscreants’ Global Bust-Out”, is 230 pages long. DeepCapture will be publishing it in approximately 25 installments over the coming weeks. -

The 9/11 Commission Report

THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States official government edition For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 0-16-072304-3 CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

AL QAIDA's SPONSORS and PARTNERS in the BUSINESS COMMUNITY 376. Al Qaida Has Established Numerous For-Profit Businesses Throug

AL QAIDA’S SPONSORS AND PARTNERS IN THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY 376. Al Qaida has established numerous for-profit businesses throughout the world, to augment the funding it receives from its State sponsors, wealthy donors and the charities and banks operating within its infrastructure. 377. Like al Qaida’s charity and banking partners, these businesses operate as fully integrated components of al Qaida’s financial and logistical infrastructure. 378. While in Sudan, Osama bin Laden established numerous businesses to provide income for al Qaida’s operations. These business ventures included: Wadi al- Aqiq Company, Ltd, a holding firm; Ladin International Company, an import/export concern; Taba Investment Company, Ltd., a currency trading firm; al-Hijrah for Construction and Development, a construction enterprise which performed several significant infrastructure projects on behalf of the ruling National Islamic Front; and the Themar al Mubaraka Company, an agricultural concern. 379. Among the projects bin Laden’s al-Hijrah Construction firm performed for the Sudanese Government were the construction of the Tahaddi Road linking Khartoum with Port Sudan, and the construction of a modern international airport near Port Sudan. 380. Osama bin Laden’s al-Hijrah Construction firm received significant support in relation to the projects it performed in Sudan from the Saudi Binladin Group, a Saudi Arabia conglomerate established by bin Laden’s father, Mohamed bin Laden, and owned to this date by members of the bin Laden family, including Osama bin Laden. 381. Saudi Binladin Group is run by Osama bin Laden’s brother, Bakr bin Laden, and the board of directors includes Saleh Gazaz, Mohammed Baharuth, Abdullah bin Said, Mohammed Nur Rahimi, Tarek bin Laden, and Omar bin Laden. -

View/Print Page As PDF

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds Checkbook Jihad by Matthew Levitt May 12, 2011 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Matthew Levitt Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler Fellow and director of the Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence at The Washington Institute. Articles & Testimony The raid that killed Usama bin Laden may finally shed light on the financial network behind al-Qaeda. errorist financiers must be under tremendous stress since news broke that U.S. Navy SEALs killed Osama bin T Laden and seized hard drives and other electronic media from his safe house. Intelligence analysts and document exploitation ("Doc X") specialists are reportedly already sifting through this intelligence treasure trove and have found evidence of notional al Qaeda plots, including aspirational plans to attack the U.S. train system, and more. In all likelihood, the files will include clues pointing to bin Laden's money trail as well. This puts people like Abd al-Hamid al-Mujil in an uncomfortable position. Described by fellow jihadists as the "million-dollar man" for his successful fundraising on behalf of al Qaeda and other jihadi groups, Mujil directed the office of the International Islamic Relief Organization (IIRO), a charity in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Both he and the IIRO office he headed were designated as terrorist entities by the U.S. Treasury Department in 2006. But even if being "named and shamed" forced Mujil out of the terror-finance business, there are many others just like him. Just this week, David Cohen, the head of the Treasury Department's Terrorism and Financial Intelligence branch, told CNN that major donors from the Gulf states remain the key sources of funding for the al Qaeda core. -

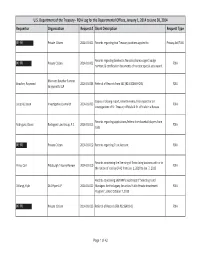

Requestor Organization Request # Short Description Request Type U.S. Department of the Treasury

U.S. Department of the Treasury - FOIA Log for the Departmental Offices, January 1, 2014 to June 30, 2014 Requestor Organization Request # Short Description Request Type (b) (6) Private Citizen 2014-01-001 Records regarding two Treasury positions applied to. Privacy Act/FOIA Records regarding banknote; Narcotics bureau agent badge (b) (6) Private Citizen 2014-01-002 FOIA number; & certification documents of narcotic special acts award. Khorrami Boucher Sumner Boucher, Raymond 2014-01-004 Referral of Records from SEC (#14-00360-FOIA) FOIA Sanguinetti, LLP Copies of closing report, referral memo, final report for all Leopold, Jason Investigative Journalist 2014-01-003 FOIA investigations of Sr. Treasury officials & Sr. officials in a Bureau Records regarding applications/letters from baseball players from Rodriguez, David Rodriguez Law Group, P.C. 2014-01-013 FOIA Cuba (b) (6) Private Citizen 2014-01-012 Records regarding Trust Account FOIA Records concerning the licensing of firms doing business with or in Prine, Carl Pittsburgh Tribune-Review 2014-01-019 FOIA the nation of Iran by OFAC from Jan. 1, 2010 to Jan. 7, 2013 Records concerning SIGTARP's audit report "Selecting Fund DiGangi, Kyle DLA Piper LLP 2014-01-022 Managers for the Legacy Securities Public-Private Investment FOIA Program", dated October 7, 2010 (b) (6) Private Citizen 2014-01-025 Referral of Records (FBI #1216401-0) FOIA Page 1 of 42 U.S. Department of the Treasury - FOIA Log for the Departmental Offices, January 1, 2014 to June 30, 2014 Requestor Organization Request # Short Description Request Type (b) (6) Private Citizen 2014-01-026 Referral of Documents from EOUSA #13-1079 FOIA Lockhart, Randall Federal Defender Office 2014-01-024 Records regarding New South Federal Savings Bank FOIA Congressional correspondence between Department of the (b) (6) Private Citizen 2014-01-021 Treasury and Sen. -

2 the Foundation of the New Terrorism

Final1-4.4pp 7/17/04 9:12 AM Page 47 2 THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 2.1 A DECLARATION OF WAR In February 1998, the 40-year-old Saudi exile Usama Bin Ladin and a fugitive Egyptian physician,Ayman al Zawahiri, arranged from their Afghan headquar- ters for an Arabic newspaper in London to publish what they termed a fatwa issued in the name of a “World Islamic Front.”A fatwa is normally an inter- pretation of Islamic law by a respected Islamic authority,but neither Bin Ladin, Zawahiri, nor the three others who signed this statement were scholars of Islamic law.Claiming that America had declared war against God and his mes- senger, they called for the murder of any American, anywhere on earth, as the “individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it.”1 Three months later, when interviewed in Afghanistan by ABC-TV, Bin Ladin enlarged on these themes.2 He claimed it was more important for Mus- lims to kill Americans than to kill other infidels.“It is far better for anyone to kill a single American soldier than to squander his efforts on other activities,” he said.Asked whether he approved of terrorism and of attacks on civilians, he replied:“We believe that the worst thieves in the world today and the worst terrorists are the Americans. Nothing could stop you except perhaps retalia- tion in kind.We do not have to differentiate between military or civilian. As far as we are concerned, they are all targets.” Note: Islamic names often do not follow the Western practice of the consistent use of surnames. -

Monograph on Terrorist Financing

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States Monograph on Terrorist Financing ________________ Staff Report to the Commission John Roth Douglas Greenburg Serena Wille Preface The Commission staff organized its work around specialized studies, or monographs, prepared by each of the teams. We used some of the evolving draft material for these studies in preparing the seventeen staff statements delivered in conjunction with the Commission’s 2004 public hearings. We used more of this material in preparing draft sections of the Commission’s final report. Some of the specialized staff work, while not appropriate for inclusion in the report, nonetheless offered substantial information or analysis that was not well represented in the Commission’s report. In a few cases this supplemental work could be prepared to a publishable standard, either in an unclassified or classified form, before the Commission expired. This study is on terrorist financing. It was prepared principally by John Roth, Douglas Greenburg, and Serena Wille, with editing assistance from Alice Falk. As in all staff studies, they often relied on work done by their colleagues. This is a study by Commission staff. While the Commissioners have been briefed on the work and have had the opportunity to review earlier drafts of some of this work, they have not approved this text and it does not necessarily reflect their views. Philip Zelikow Terrorist Financing Staff Monograph Table of Contents INTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................ 2 AL QAEDA’S MEANS AND METHODS TO RAISE, MOVE, AND USE MONEY.......................... 17 GOVERNMENT EFFORTS BEFORE AND AFTER THE SEPTEMBER 11 ATTACKS................ 30 COMBATING TERRORIST FINANCING IN THE UNITED STATES: THE ROLE OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS.................................................................................................................