Jun 1 4 2007 Libraries I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Barcelona Intensive Course Abroad Itinerary Draft: Subject to Updating

2019 BARCELONA INTENSIVE COURSE ABROAD ITINERARY DRAFT: SUBJECT TO UPDATING Sunday Arrival in BarCelona Sept. 8 Morning Transport from El Prat Airport: Take the train* to Plaça de Sants; transfer to Metro* Line 1 (direction Fondo); take metro to Marina; walk to the residencia THS Campus Marina (address below).* A sinGle, 1 zone ticket costs 2 €, a Group can share a T-10 ticket (10 rides for 9.25 €). For more transit information, Go to: www.tmb.cat/en/el-teu- transport. NOTE: Prepare today for the week’s transit needs: ** purchase a 5- day travel card, to be initiated on the morning of Sunday, September 6th. ** Points of sale: www.tmb.cat/en/bitllets-i-tarifes/-/bitllet/52 - Metro automatic vendinG machines Intensive Course Abroad beGins in Barcelona at our accommodations: THS Campus Marina Carrer Sancho de Ávila, 22 08018 Barcelona, Spain Telephone: + 34 932178812 Web: www.melondistrict.com/en/location Metro: L1-Marina Afternoon Meet for an orientation; Walk to: 15:00 Museu del Disseny de BarCelona Architecture: MBM Studio (Martorell-BohiGas-Mackay), 2013 Plaça de les Glories Catalanes, 37 Dinner Group dinner (paid for by program), location to be determined 19:00 pm Monday Exploring great designs by Gaudi and DomèneCh; The Sept. 9 Contemporary City around the Plaça de las Glòries Catalanes, the Avinguda Diagonal, and DistriCt 22@bcn. Lobby 8:15 BrinG Metro Card and Articket. Early start! Morning BasiliCa de la Sagrada Familia 9:00-12:00 Architect: Antoni Gaudí, 1883-1926, onGoinG work by others Visit/SketChing Carrer de Mallorca, 401 1 Metro: L2+5 SaGrada Familia (open daily 9am-8pm / 13 or 14,30 € ) LunCh Many fast food options nearby 12:00-12:45 Afternoon Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau 13:00-14:00 Architect: Lluís Domènech i Montaner, 1901-1930 (under renovation as a museum and cultural center, access currently limited) Sant Pau Maria Claret, 167. -

THE VIVA GUIDE Barcelona Welcome To

THE VIVA GUIDE Barcelona Welcome to_ This guide was produced for you by the Viva Barcelona team. Graphic Design by Carmen Galán [carmengalan.com] BARCELONA Barcelona is the 10th most visited city in the world and the third most visited in Europe after London and Paris, with several million tourists every year. With its ‘Rambles’, Barcelona is ranked the most popular city to visit in Spain and it now attracts some 7.5 million tourists per year. Barcelona has a typical Mediterranean climate. The winter is relatively mild and the summer is hot and humid. The rainy seasons are the once in between autumn and spring. There are very few days of extreme temperature, heat or cold. Every 24th September, Barcelona celebrates it’s annual festival, La Mercè – corresponding to the day of its patron saint. It comprises of some 600 events, from concerts and all kinds of local, cultural attractions including the human tower building, els Castellers, erected by groups of women, men and children, representing values such as solidarity, effort and the act of achievement. Children are the real stars of this tradition, they climb to the very top of the human castell expressing strength over fragility. 4 5 Since 1987, the city has been Passeig de Gràcia being the most Districts divided into 10 administrative important avenue that connects the districts: Ciutat Vella, Eixample, central Plaça Catalunya to the old Sants- Montjuic, Les Corts, town of Gràcia, while Avinguda Sarriá-Sant Gervasi, Gràcia, Diagonal cuts across the grid Horta-Guinardò, Nou Barris, diagonally and Gran Via de les Corts Sant Andreu, Sant Martì. -

Download Presentation Notes

2020.02.17 Barcelona/Bilbao Tour Presentation (30 min.) Some slides of the architecture we will see on the tour. Present slides chronologically which is different from the trip itinerary, this is a brief preview of the class teaching this summer (Gaudi’s 5 key dates), which was structured to be a prelude for the trip. Beautiful itinerary of Gaudi: playful Batlló/Mila, Vicens; mag.opus Sagrada; essence Dragon/Crypt; serene Park; finale Bilbao. Many other treats: Barcelona Rambla, ancient bullfighting ring, Barcelona Pavilion, 92 Olympic village/park, Miró museum. Catalan brickwork Trencadis discarded parabolic signatures metalwork 1885 Pavellons Güell Dragon Gate (Tue.) first use of Trencadis Mosaic, where we see Gaudi’s resourcefulness, frugality, creativity. A study of Gaudi’s work explores this human trait that will be needed for our survival on a rapidly changing planet. By use of discarded, broken, fragmented materials as decoration, Gaudi finds redemption, a humility willing to consider all. corner cast/wrought plasticity ventilators Mudéjar contraptions Casa Vicens (Mon. - interior) 1883-1888 organic form discarded personalized Park Güell bench (Wed. - interior) 1903-1914 mosaic ventilators parabolic Jean Nouvel: Agbar Tower (Tue.) 1999-2004 Norman Foster: Bilbao Underground Station (Fri.) 1995 parabolic natural honest (+7 min.) 1892 Sagrada Familia Nativity Façade (Mon. – interior) experiments Natural Form [honest truth, taboos, answers in nature] honest organic natural mosaic honest Mies: Barcelona Pavilion (Wed. - interior) 1928-1929 IMB: Vizcaya Foral Library (Sat.) 2007 inclined reuse contraption weight (+9 min.) 1898 Colònia Güell Crypt model (Tue. - interior) equilibriated structures gravity thrusts passive tree work with, not against Park Güell colonade viaduct (Wed. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

The Ship of Theseus Identity and the Barcelona Pavilion(S)

The Ship of Theseus Identity and the Barcelona Pavilion(s) Lance Hosey NewSchool of Architecture & Design Built in 1929 and demolished in 1930, the Figure 1. Opposite page, top: Barcelona Pavilion, 1929 and 1986 (photographed 2009). Viewed from Barcelona Pavilion was rebuilt on the original the northeast. The German tricolor flag flew over the 1929 pavilion; the flag of Barcelona flies over the site in 1986. Is it the “same” building? Many current structure. (Left: Photograph by Berliner Bild Bericht. Opposite page, right: Photograph by Pepo architects and critics question the reconstruction’s Segura. Courtesy of Fundació Mies van der Rohe.) authenticity, dismissing it as a “fake.” Why the Figure 2. Opposite page, middle: Barcelona Pavilion, 1929 and 1986 (photographed 2009). pavilion has inspired such doubt is an important North courtyard with George Kolbe sculpture, Alba (“Dawn”). The original cast was plaster; the WRSLFEHFDXVHLWUHODWHVWRWKHYHU\GH¿QLWLRQV current cast is bronze. (Left: Photograph by Berliner Bild Bericht. Right: Photograph by Pepo Segura. of architecture. What determines a building’s Courtesy of Fundació Mies van der Rohe.) identity—form, function, context, material, or Figure 3. Opposite page, bottom: Barcelona Pavilion, 1929 and 1986 (photographed 2009). something else? As a historically important View across the podium reflecting pool from the southeast. (Left: Photograph by Berliner work that has existed in more than one instance, Bild Bericht. Right: Photograph by Pepo Segura. Courtesy of Fundació Mies van der Rohe.) the Barcelona Pavilion offers an extraordinary opportunity to consider this question. Examining Goldberger.¡ The architects of the reconstruction—Ignasi Solà-Morales, the distinctions between the two structures Cristian Cirici, and Fernando highlights conventional standards of critical Ramos—admitted their own “tremor of doubt,” writing that rebuilding such evaluation, exposing architecture’s core values a familiar landmark was a “traumatic and interrogating the very concept of preservation. -

Descriptive Memory

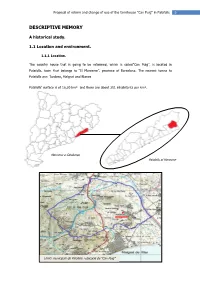

Proposal of reform and change of use of the farmhouse "Can Puig" in Palafolls 9 DESCRIPTIVE MEMORY A historical study. 1.1 Location and environment. 1.1.1 Location. The country house that is going to be reformed, which is called"Can Puig", is located in Palafolls, town that belongs to “El Maresme”, province of Barcelona. The nearest towns to Palafolls are: Tordera, Malgrat and Blanes Palafolls’ surface is of 16,20 km² and there are about 251 inhabitants per km². Maresme a Catalunya Palafolls al Maresme Límits municipals de Palafolls i ubicació de “Can Puig” 10 Proposal for reform and change of use of the house "Can Puig" in Palafolls FIXED AND LOCATION OF SITE Name of the farmhouse Can Puig The Building Typology Isolated Region Maresme Municipality Palafolls Geographical height 16 m above the sea level Seismicity Low City Limits Tordera limited to the north, to the North for spite, east to Blanes (I) to the North West Santa Susana County boundaries Bounded to the north by Valles to the Eastern Mediterranean by sea, by Barcelona to the South and West-east forest. 1.1.2 Geography Relief: Palafolls is located to the northeastern border in the Maresme region (Barcelona) by Tordera limit of frontier with the region of La Selva and while the province of Girona. The Municipal term is 3.16 km ², and it’s 16 m above the sea level.. The first of December of 2006 population was 8,102 inhabitants. The most popular occupation in Palafoll is teh tourism industry. The central core is called Ferreries and two of the main neirhborhoods are Sta. -

Ideas and Practices for the European City

JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURAL CULTURE 2017 JOELHO # 08 IDEAS AND PRACTICES FOR THE EUROPEAN CITY —— Guest Editors: José António Bandeirinha Luís Miguel Correia Nelson Mota Ákos Moravánszky Irina Davidovici Matthew Teissmann Alexandre Alves Costa Chiara Monterumisi Harald Bodenschatz Joana Capela de Campos Vitor Murtinho Platon Issaias Kasper Lægring Nuno Grande Roberto Cremascoli Exhibition History of Architecture III / IV Biographies of Power: Personalities and Architectures Jorge Figueira and Bruno Gil EDARQ JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURAL CULTURE 2017 JOELHO # J08 IDEAS AND PRACTICES FOR THE EUROPEAN CITY —— Guest Editors: José António Bandeirinha Luís Miguel Correia Nelson Mota Ákos Moravánszky Irina Davidovici Matthew Teissmann Alexandre Alves Costa Chiara Monterumisi Harald Bodenschatz Joana Capela de Campos Vitor Murtinho Platon Issaias Kasper Lægring Nuno Grande Roberto Cremascoli Exhibition History of Architecture III / IV Biographies of Power: Personalities and Architectures Jorge Figueira and Bruno Gil em cima do joelho série II: Joelho Editores / Editors JOELHO Edição / Publisher Tipografia / Typography Contactos / Contacts Jorge Figueira (CES, DARQ, UC) e|d|arq – Editorial do Departamento Logótipo Joelho: Garage, Desenhada [email protected] Gonçalo Canto Moniz (CES, DARQ, UC) de Arquitectura Faculdade de em 1999 por Thomas Hout-Marchand, [email protected] — Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Editada pela sua editora 256TM — JOELHO 8 de Coimbra / Department of Joelho Website Ideas and Practices for Architecture, Faculty of Sciences and JOELHO VIII: Neutraface Slab, http://impactum-journals.uc.pt/index. the European City Technology, University of Coimbra desenhada em 2009 por Susana php/joelho/index — — Carvalho e Kai Bernau, sob direcção https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/ Editores convidados / Guest Editors Design artistica de Christian Schwartz e Ken node/84925 José António Bandeirinha R2 · www.r2design.pt Barber. -

FDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC$23.03 Appendicestwo Cn Western Art, Two on Architect Ire, and One Each on Nonwestern Art, Nonwestern Musi

DOCDPENT RESUME ED 048 316 24 TE 499 838 AUTHOR Colwell, Pichard TTTLE An Approach to Aesthetic Education, Vol. 2. Final Report. INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana, Coll. of Education. SPCNS AGENCY Office of Education (DREW), Washington, D.0 Bureau of Research. 'aUREAU NO BR-6-1279 PUB DATE Sep 70 CONTRACT OEC-3-6-061279-1609 NOTE 680p. EERS PRICE FDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC$23.03 DESCRIPTORS *Architecture, *Art Education, *Cultural Enrichment, *Dance, Film Study, Inst,.uctional Materials, Lesson Plans, Literature, Music Education, Non Western Civilization, *Teaching Techniques, Theater Arts, Western Civilization ABSTRACT Volume 2(See also TE 499 637.) of this aesthetic education project contains the remiinirig 11 of 17 report appendicestwo cn Western art, two on architect ire, and one each on Nonwestern art, Nonwestern music, dance, theatre, ana a blif outline on film and literature--offering curriculum materials and sample lesson plans.The. last two appendices provide miscellaneous informatics (e.g., musi,:al topics not likely to be discussed with this exemplar approach) and a "uorking bibliography." (MF) FINACVPORT Contract Number OEC3,6-061279-1609 AN APPROACH TO AESTHETIC EDUCATION VOLUME II September 1970 el 111Q1 7). ,f; r ri U.S. DepartmentDepartment of Health, Education, and Welfore Office of Education COLLEGE OF EDUCATION rIVERSITY 01. ILLINOIS Urbana - Champaign Campus 1 U S DEPARTMENT Of HEALTH, EDUCATION A WELFARE OFFICE Of EDUCATION THIS DOCUMikl HAS REIN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE POISON OP OOGANITATION ORIOINATIOLS IT POINTS Of VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE Of EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. AN APPROACH TO AESTHETIC EDUCATION Contract Number OEC 3-6-061279-1609 Richard Colwell, Project Director The research reported herein was performed pursuant to a contract with the Offices of Education, U.S. -

Committee Approval Form

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ HERMENEUTICS OF ARCHITECTURAL INTERPRETATION: THE WORK IN THE BARCELONA PAVILION A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Department of Architecture and Interior Design of the College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning 2002 By Maroun Ghassan Kassab B Arch, Lebanese American University Jbeil, Lebanon 1999 Committee: Professor John E. Hancock (Chair) James Bradford, Adj. Instructor Aarati Kanekar, Assistant Professor ABSTRACT Architectural interpretation has always been infiltrated by the metaphysics of Presence. This is due to the interpreter’s own background that uses the vocabulary of metaphysics, and due to the predetermined set of presuppositions the interpreter inherited from the metaphysical tradition itself. As a consequence what is to be interpreted has constantly been taken -

Art and Politics at the Neapolitan Court of Ferrante I, 1458-1494

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: KING OF THE RENAISSANCE: ART AND POLITICS AT THE NEAPOLITAN COURT OF FERRANTE I, 1458-1494 Nicole Riesenberger, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Professor Meredith J. Gill, Department of Art History and Archaeology In the second half of the fifteenth century, King Ferrante I of Naples (r. 1458-1494) dominated the political and cultural life of the Mediterranean world. His court was home to artists, writers, musicians, and ambassadors from England to Egypt and everywhere in between. Yet, despite its historical importance, Ferrante’s court has been neglected in the scholarship. This dissertation provides a long-overdue analysis of Ferrante’s artistic patronage and attempts to explicate the king’s specific role in the process of art production at the Neapolitan court, as well as the experiences of artists employed therein. By situating Ferrante and the material culture of his court within the broader discourse of Early Modern art history for the first time, my project broadens our understanding of the function of art in Early Modern Europe. I demonstrate that, contrary to traditional assumptions, King Ferrante was a sophisticated patron of the visual arts whose political circumstances and shifting alliances were the most influential factors contributing to his artistic patronage. Unlike his father, Alfonso the Magnanimous, whose court was dominated by artists and courtiers from Spain, France, and elsewhere, Ferrante differentiated himself as a truly Neapolitan king. Yet Ferrante’s court was by no means provincial. His residence, the Castel Nuovo in Naples, became the physical embodiment of his commercial and political network, revealing the accretion of local and foreign visual vocabularies that characterizes Neapolitan visual culture. -

THE BARCELONA PAVILION AS LANDSCAPE GARDEN: MODERNITY and the PICTURESQUE Author(S): Caroline Constant Source: AA Files, No

THE BARCELONA PAVILION AS LANDSCAPE GARDEN: MODERNITY AND THE PICTURESQUE Author(s): Caroline Constant Source: AA Files, No. 20 (Autumn 1990), pp. 46-54 Published by: Architectural Association School of Architecture Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29543706 . Accessed: 26/09/2014 12:50 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Architectural Association School of Architecture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to AA Files. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Fri, 26 Sep 2014 12:50:54 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE BARCELONA PAVILION AS LANDSCAPE GARDEN MODERNITY AND THE PICTURESQUE Caroline Constant 'A work of architecture must not stand as a finished and self afforded Mies the freedom to pursue the expressive possibilities of sufficient object. True and pure imagination, having once entered the discipline. During the 1920s he had begun to abandon the formal the stream of the idea that it expresses, has to expand forever logic of the classical idiom, with itsmimesis of man and nature, in beyond thiswork, and itmust venture out, leading ultimately to the favour of specifically architectural means. -

RAFAEL GUASTAVINO MORENO Inventiveness in 19Th Century Architecture by Jaume Rosell Colomina

RAFAEL GUASTAVINO MORENO Inventiveness in 19th century architecture by Jaume Rosell Colomina This article was published in Catalan in pa. 494-522 by CAMARASA, Josep M.; ROCA, Antoni (dir.): Ciència i Tècnica als Països Catalans : una aproximació biogràfica (2v). Fundació Catalana per a la Recerca. Barcelona, 1995. The English version, revised by the author, was translated by Edward Krasny. An English version of this text was published in pp. 45-49 by TARRAGÓ, Salvador (editor): Guastavino Co. (1885-1962) : Catalogue of works in Catalonia and America. Col·legi d'Arquitectes de Catalunya. Barcelona, 2002. (ISBN 84-88258-65-8). Revised version, January 2010. Catalan and Spanish version in: https://upcommons.upc.edu/e-prints/browse?type=author&value=Rosell%2C+Jaume In memory of my father, Pere Rosell i Millach RAFAEL GUASTAVINO MORENO València, 1842 – Black Mountains, North Carolina, 1908 Key words: architecture, industrial architecture, cement, construction, cohesive construction, iron, brick, flat brick masonry, master builders, Modernisme, fire resistance, vaults. The contribution of Valencian Rafael Guastavino Moreno to Architecture was especially important in the technical area. He was the leading moderniser of an ancient building technique using flat brick masonry techniques, above all to erect vaults. Guastavino would later transfer these techniques from Catalonia to the United States of America, where he founded a family company that built, over two generations, more than one thousand buildings, many of them of great importance. These two accomplishments represent a notable contribution to contemporary Architecture: more so if we take into account a series of technological reflections and proposals that also constitute a contribution to the modernisation of construction, insofar as they entail an effort to understand the behaviour of and ways in which the new materials worked.