The State of Britain's Larger Moths Report 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; Download Unter

©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Entomofauna ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ENTOMOLOGIE Band 28, Heft 28: 377-388 ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. November 2007 Phytophagous Noctuidae (Lepidoptera) of the Western Black Sea Region and their ichneumonid parasitoids Z. OKYAR & M. YURTCAN Abstract Eleven agricultural and silviculturally important species of Noctuidae and their parasitoids were determined in 33 localities from the Western Black Sea region between 2001 and 2004. The ichneumonid biological control agents Enicospilus ramidulus, Barylypa amabilis and Itoplectis alternans were obtained by rearing the host larvae. K e y w o r d s : Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, parasitoidism, Western Black Sea Region, Turkey Zusammenfassung 11 land- und forstwirtschaftlich bedeutende Noctuidae-Arten einschließlich ihrer Parasitoide aus 33 Standorten des Gebietes des westlichen Schwarzen Meeres wurden im Zeitraum 2001 bis 2004 studiert. Ichneumonidae der Arten Enicospilus ramidulus, Barylypa amabilis and Itoplectis alternans konnten durch Aufzucht der Wirtslarven festgestellt werden. 377 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Introduction The Noctuidae is the largest family of the Lepidoptera. Larvae of some species are par- ticularly harmful to agricultural and silvicultural regions worldwide. Consequently, for years intense efforts have been carried out to control them through chemical, biological, and cultural methods (LIBURD et al. 2000; HOBALLAH et al. 2004; TOPRAK & GÜRKAN 2005). In the field, noctuid control is often carried out by parasitoid wasps (CHO et al. 2006). Ichneumonids are one of the most prevalent parasitoid groups of noctuids but they also parasitize on other many Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Diptera and Araneae (KASPARYAN 1981; FITTON et al. 1987, 1988; GAULD & BOLTON 1988; WAHL 1993; GEORGIEV & KOLAROV 1999). -

Scope: Munis Entomology & Zoology Publishes a Wide Variety of Papers

732 _____________Mun. Ent. Zool. Vol. 7, No. 2, June 2012__________ STRUCTURE OF LEPIDOPTEROCENOSES ON OAKS QUERCUS DALECHAMPII AND Q. CERRIS IN CENTRAL EUROPE AND ESTIMATION OF THE MOST IMPORTANT SPECIES Miroslav Kulfan* * Department of Ecology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Comenius University, Mlynská dolina B-1, SK-84215 Bratislava, SLOVAKIA. E-mail: [email protected] [Kulfan, M. 2012. Structure of lepidopterocenoses on oaks Quercus dalechampii and Q. cerris in Central Europe and estimation of the most important species. Munis Entomology & Zoology, 7 (2): 732-741] ABSTRACT: On the basis of lepidopterous larvae a total of 96 species on Quercus dalechampii and 58 species on Q. cerris were recorded in 10 study plots of Malé Karpaty and Trnavská pahorkatina hills. The families Geometridae, Noctuidae and Tortricidae encompassed the highest number of found species. The most recorded species belonged to the trophic group of generalists. On the basis of total abundance of lepidopterous larvae found on Q. dalechampii from all the study plots the most abundant species was evidently Operophtera brumata. The most abundant species on Q. cerris was Cyclophora ruficiliaria. Based on estimated oak leaf area consumed by a larva it is shown that Lymantria dispar was the most important leaf-chewing species of both Q. dalechampii and Q. cerris. KEY WORDS: Slovakia, Quercus dalechampii, Q. cerris, the most important species. About 300 Lepidoptera species are known to damage the assimilation tissue of oaks in Central Europe (Patočka, 1954, 1980; Patočka et al.1999; Reiprich, 2001). Lepidoptera larvae are shown to be the most important group of oak defoliators (Patočka et al., 1962, 1999). -

Contributions to Knowledge of the Geometrid Fauna of Bulgaria and Greece, with Four Species New for the Greek Fauna (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) (Plate 12)

Esperiana Band 18: 221- 224 Bad Staffelstein; Schwanfeld, 02. Dezember 2013 ISBN 978-3-938249-04-8 Contributions to knowledge of the geometrid fauna of Bulgaria and Greece, with four species new for the Greek fauna (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) (plate 12) Balázs TÓTH, János BABICS & Balázs BENEDEK Abstract During a tour led by the authors to Bulgaria and Greece in March, 2013, a total of 19 geometrid species were observed at five localities. Biston achyra WEHRLI, 1936, Agriopis marginaria (FABRICIUS, 1776), A. leucophaearia ([DENIS & SCHIffERMÜLLER], 1775) and Erannis ankeraria (STAUDINGER, 1861) were found for the first time in Greece. An entirely new habitat type is included to the biotope range of E. ankeraria, arousing the possibility of this species being widespread in the Mediterranean countries. The authors hope that these observations will encourage attention to the exploration of the populations, thereby contributing to the more efficient protection of this species. Checklists are given to each collecting events. Key words: Biston, Agriopis, Erannis, Bulgaria, Greece, new data, oak woodland, macchia-scrub, soil types Introduction Biston achyra WEHRLI, 1936 was described from Asia Minor and subsequently found in Ukraine (KOSTJUK, 1990), the Levant (KOSTJUK, 1991) and Russia (SINEV, 2008). This species can be distinguished from its relative B. strataria (HUFNAGEL, 1767) by its considerably smaller size, more elongated forewing, and the presence of discal spot on the hindwing. Agriopis marginaria (FABRICIUS, 1776) and A. leucophaearia ([DENIS & SCHIFFERMÜLLER], 1775) are both frequent and widespread in Europe. The former species is distributed from the Iberian Peninsula to the Urals and the Caucasus Mts., and is also present in Asia Minor. -

List of UK BAP Priority Terrestrial Invertebrate Species (2007)

UK Biodiversity Action Plan List of UK BAP Priority Terrestrial Invertebrate Species (2007) For more information about the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) visit https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/uk-bap/ List of UK BAP Priority Terrestrial Invertebrate Species (2007) A list of the UK BAP priority terrestrial invertebrate species, divided by taxonomic group into: Insects, Arachnids, Molluscs and Other invertebrates (Crustaceans, Worms, Cnidaria, Bryozoans, Millipedes, Centipedes), is provided in the tables below. The list was created between 1995 and 1999, and subsequently updated in response to the Species and Habitats Review Report published in 2007. The table also provides details of the species' occurrences in the four UK countries, and describes whether the species was an 'original' species (on the original list created between 1995 and 1999), or was added following the 2007 review. All original species were provided with Species Action Plans (SAPs), species statements, or are included within grouped plans or statements, whereas there are no published plans for the species added in 2007. Scientific names and commonly used synonyms derive from the Nameserver facility of the UK Species Dictionary, which is managed by the Natural History Museum. Insects Scientific name Common Taxon England Scotland Wales Northern Original UK name Ireland BAP species? Acosmetia caliginosa Reddish Buff moth Y N Yes – SAP Acronicta psi Grey Dagger moth Y Y Y Y Acronicta rumicis Knot Grass moth Y Y N Y Adscita statices The Forester moth Y Y Y Y Aeshna isosceles -

Download List of Notable Species in Edinburgh

Group Scientific name Common name International / UK status Scottish status Lothian status marine mammal Balaenoptera acutorostrata Minke Whale HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 marine mammal Delphinus delphis Common Dolphin Bo HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 marine mammal Halichoerus grypus Grey Seal Bo HSD marine mammal Lagenorhynchus albirostris White-beaked Dolphin Bo HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 marine mammal Phocoena phocoena Common Porpoise Bo GVU HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 marine mammal Tursiops truncatus Bottle-Nosed Dolphin Bo HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 terrestrial mammal Arvicola terrestris European Water Vole PS W5 SBL Sc5 terrestrial mammal Erinaceus europaeus West European Hedgehog PS terrestrial mammal Lepus europaeus Brown Hare PS SBL Sc5 terrestrial mammal Lepus timidus Mountain Hare HSD PS SBL Sc5 terrestrial mammal Lutra lutra European Otter HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 terrestrial mammal Meles meles Eurasian Badger BA SBL SO1 terrestrial mammal Micromys minutus Harvest Mouse PS E? terrestrial mammal Myotis daubentonii Daubenton's Bat Bo HSD W5 SBL terrestrial mammal Myotis nattereri Natterer's Bat Bo HSD W5 SBL terrestrial mammal Pipistrellus pipistrellus Pipistrellus pipistrellus Bo HSD W5 terrestrial mammal Pipistrellus pygmaeus Soprano Pipistrelle PS SBL terrestrial mammal Plecotus auritus Brown Long-eared Bat Bo HSD PS W5 SBL terrestrial mammal Sciurus vulgaris Eurasian Red Squirrel PS W5 SBL SO1 bird Accipiter nisus Eurasian Sparrowhawk Bo bird Actitis hypoleucos Common Sandpiper Bo bird Alauda arvensis Sky Lark BCR BD SBL bird Alcedo atthis Common Kingfisher BCA W1 SBL bird Anas -

Buletinul Известия Journal

Buletinul AŞM. Ştiinţele vieţii. Nr. 3(330) 2016 Buletinul AŞM. Ştiinţele vieţii. Nr. 3(330) 2016 ISSN 1857-064X Categoria B BULETINUL ACADEMIEI DE ŞTIINŢE A MOLDOVEI Ştiinţele vieţii ИЗВЕСТИЯ АКАДЕМИИ НАУК МОЛДОВЫ Науки о жизНи JOURNAL OF ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF MOLDOVA LIFE SCIENCES 3 (330) 2016 Chişinău Buletinul AŞM. Ştiinţele vieţii. Nr. 3(330) 2016 Buletinul AŞM. Ştiinţele vieţii. Nr. 3(330) 2016 COLEGIUL DE REDACŢIE Redactor-şef Valentina CIOCHINĂ Teodor FURDUI Institutul de Fiziologie şi Sanocreatologie al Aca- Institutul de Fiziologie şi Sanocreatologie al Aca- demiei de Ştiinţe a Moldovei, Laboratorul Fiziolo- demiei de Ştiinţe a Moldovei, Laboratorul Fiziolo- gia stresului, adaptării şi Sanocreatologie generală, gia stresului, adaptării şi Sanocreatologie generală, doctor, conferenţiar. Adresa: str. Academiei, 1, MD- academician, doctor habilitat, profesor. Adresa: str. 2028 Chişinău, Republica Moldova. Tel.: (+373)22 Academiei, 1, MD-2028 Chişinău, Republica Mol- 725152; E-mail: [email protected] dova. Tel.: (+373)22 725209; (+373) 069972538 Gheorghe DUCA Redactor-şef adjunct Institutul de Chimie al Academiei de Ştiinţe a Moldovei, Centrul Chimie Fizică şi Nanocompozite, Ion TODERAŞ academician, doctor habilitat, profesor. Adresa: Institutul de Zoologie al Academiei de Ştiinţe bd.Ştefan cel Mare, 1, MD-2001 Chişinău, a Moldovei, Centrul de Cercetare a Invaziilor Republica Moldova. Tel/Fax.: (+373)22 271478; Biologice, Laboratorul de Sistematică şi Filogenie E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] moleculară, academician, doctor habilitat, profesor. Adresa: str. Academiei, 1, MD-2028 Chişinău, Maria DUCA Republica Moldova. Tel.: (+373)22 731255; Universitatea Academiei de Ştiinţe a Moldovei, E-mail:[email protected] Centrul universitar Genetică funcţională, Secretar responsabil academician, doctor habilitat, profesor. -

Somerset's Ecological Network

Somerset’s Ecological Network Mapping the components of the ecological network in Somerset 2015 Report This report was produced by Michele Bowe, Eleanor Higginson, Jake Chant and Michelle Osbourn of Somerset Wildlife Trust, and Larry Burrows of Somerset County Council, with the support of Dr Kevin Watts of Forest Research. The BEETLE least-cost network model used to produce Somerset’s Ecological Network was developed by Forest Research (Watts et al, 2010). GIS data and mapping was produced with the support of Somerset Environmental Records Centre and First Ecology Somerset Wildlife Trust 34 Wellington Road Taunton TA1 5AW 01823 652 400 Email: [email protected] somersetwildlife.org Front Cover: Broadleaved woodland ecological network in East Mendip Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Policy and Legislative Background to Ecological Networks ............................................ 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 Government White Paper on the Natural Environment .............................................. 3 National Planning Policy Framework ......................................................................... 3 The Habitats and Birds Directives ............................................................................. 4 The Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010 .................................. -

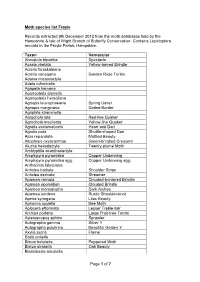

Page 1 of 7 Moth Species List Froyle Records

Moth species list Froyle Records extracted 9th December 2012 from the moth databases held by the Hampshire & Isle of Wight Branch of Butterfly Conservation. Contains Lepidoptera records in the Froyle Parish, Hampshire. Taxon Vernacular Abrostola tripartita Spectacle Acasis viretata Yellow-barred Brindle Acleris forsskaleana Acleris variegana Garden Rose Tortrix Adaina microdactyla Adela rufimitrella Agapeta hamana Agonopterix arenella Agonopterix heracliana Agriopis leucophaearia Spring Usher Agriopis marginaria Dotted Border Agriphila straminella Agrochola lota Red-line Quaker Agrochola macilenta Yellow-line Quaker Agrotis exclamationis Heart and Dart Agrotis puta Shuttle-shaped Dart Alcis repandata Mottled Beauty Allophyes oxyacanthae Green-brindled Crescent Alucita hexadactyla Twenty-plume Moth Amblyptilia acanthadactyla Amphipyra pyramidea Copper Underwing Amphipyra pyramidea agg. Copper Underwing agg. Anthophila fabriciana Anticlea badiata Shoulder Stripe Anticlea derivata Streamer Apamea crenata Clouded-bordered Brindle Apamea epomidion Clouded Brindle Apamea monoglypha Dark Arches Apamea sordens Rustic Shoulder-knot Apeira syringaria Lilac Beauty Aphomia sociella Bee Moth Aplocera efformata Lesser Treble-bar Archips podana Large Fruit-tree Tortrix Asteroscopus sphinx Sprawler Autographa gamma Silver Y Autographa pulchrina Beautiful Golden Y Axylia putris Flame Batia unitella Biston betularia Peppered Moth Biston strataria Oak Beauty Blastobasis adustella Page 1 of 7 Blastobasis lacticolella Cabera exanthemata Common Wave Cabera -

Agrochola Circellaris Hufn

OchrOna ŚrOdOwiska i ZasObów naturalnych vOl. 28 nO 2(72): 41-45 EnvirOnmEntal PrOtEctiOn and natural rEsOurcEs 2017 dOi 10.1515 /OsZn-2017-0014 Jolanta Bąk-Badowska *, Ilona Żeber-Dzikowska**, Jarosław Chmielewski*** The impact of brick (Agrochola circellaris Hufn.) and owlet moths (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on the health of seeds of field elms (Ulmus minor Mill.) in the landscape parks of the Świętokrzyskie Province Wpływ zrzenicówki wiązowej (Agrochola circellaris Hufn.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) na zdrowotność nasion wiązu polnego (Ulmus minor Mill.) w parkach krajobrazowych województwa świętokrzyskiego *Dr hab. Jolanta Bąk-Badowska, Institute of Biology, The Jan Kochanowski ***Dr Jarosław Chmielewski, Institute of Environmental Protection-National University, Świętokrzyska 15 St., 25-406 Kielce, e-mail: [email protected] Research, Krucza 5/11d St., 00-548 Warsaw, e-mail: [email protected] **Dr hab. Ilona Żeber-Dzikowska, Prof. Nadzw., Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, The State School of Higher Professional Education in Płock, Gałczyńskiego 28 St., 09-400 Płock; Institute of Biology, The Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce, Świetokrzyska 15 St., 25-406 Kielce; e-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Ulmus minor, seed pests, Agrochola circellaris, stand density, landscape parks, the Świętokrzyskie Province Słowa kluczowe: Ulmus minor, szkodniki nasion, Agrochola circellaris, zwarcie drzewostanu, parki krajobrazowe, województwo świętokrzyskie Abstract Streszczenie In the period of 2012–2013, a research was conducted to W latach 2012-2013 przeprowadzono badania dotyczące investigate the insects damaging the seeds of field elm (Ulmus owadów uszkadzających nasiona wiązu polnego (Ulmus minor minor Mill.). The aim of the research was to specify the damages Mill.). -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Tese Final Sandro.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE DE ÉVORA ESCOLA DE CIÊNCIAS E TECNOLOGIA Departamento de Biologia Aspetos morfológicos dos insetos e sua importância na polinização Sandro Melo Cerqueira Orientador: Anabela Belo Mestrado em Biologia da Conservação Dissertação Évora, 2015 UNIVERSIDADE DE ÉVORA ESCOLA DE CIÊNCIAS E TECNOLOGIA Departamento de Biologia UNIVERSIDADE DE ÉVORA ESCOLA DE CIÊNCIAS E TECNOLOGIA Aspetos morfológicos dos insetos e sua importância na polinização Sandro Melo Cerqueira Orientador: Anabela Belo Mestrado em Biologia da Conservação Dissertação Évora, 2015 ―O que torna as coisas desconcertantes é o seu grau de complexidade, não a sua dimensão; uma estrela é mais simples do que um inseto‖ - Martin Rees, 1999. In ―Evolution of Insects‖, David Grimaldi and Michael S. Engel, Cambridge University Press Agradecimentos Em primeiro lugar gostaria de agradecer á Associação ―A Rocha‖ pela disponibilidade em fornecer os meios logísticos e técnicos necessários para a execução deste trabalho, em especial á Prof. Paula Banza pela sua ajuda e disponibilidade, por me ter passado o seu conhecimento e me ter acompanhado ao longo de todo o trabalho. Obrigado Jens D‘Haeseleer pela ajuda na identificação dos insetos e Drª Renata Medeiros pela ajuda na parte estatística. Quero agradecer á Prof. Anabelo Belo pela sua orientação, apoio e comentários. E por fim, aos meus pais e ao meu irmão, por todo o apoio financeiro e incentivo dado. A todas as pessoas que de algum modo contribuíram para que fosse possível a realização desta dissertação, muito obrigado. Índice A. Índice de Tabelas --------------------------------------------------------------------------6 B. Índice de Figuras---------------------------------------------------------------------------7 C. Resumo---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------9 D. Abstract ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------10 1. Introdução-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------11 2. -

Climatic Condition in Mandi Distric

Research Paper Volume : 4 | Issue : 1 | January 2015 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 Taxonomic Studies on Light Trap Collected Biotechnology Species of Abraxas Leach Under Agro- KEYWORDS : Taxonomic, Genitalia, Wing, Adeagus Climatic Condition in Mandi District of Himachal Pradesh Forest Protection Division, Himalayan Forest Research Institute, Conifer Campus VIKRANT THAKUR Panthaghati, Shimla Himachal Pradesh 171009 MANOJ KUMAR Faculty of Biotechnology, Shoolini university, Solan HP-172230 ABSTRACT The light trap collection by using mercury lamp indicated that Abraxas Leach under agro-climatic condition of Mandi district of Himachal Pradesh is comprises of three species viz. Abraxas picaria Moore, Abraxas leucostola Hampson and Abraxas sylvata Scopoli. These species obatain their peak in July- August . Abraxas leucostola Hampson was found most abundant followed by Abraxas picaria Moore and Abraxas sylvata Scopoli on the basis of daily catches. The taxonomic study on these spe- cies carried out and described in detail. A key to the species of Abraxas Leach has also been provided for their easy identification. Introduction: DEX (Beccaloni et.al. 2003). The hierarchy of different moth is This moth is mostly white with brownish patches across all of given by Van Nieukerken et al. (2011) the wings. There are small areas of pale gray on the forewings and hind wings. They resemble bird droppings while resting on Result: the upper surface of leaves. The adults fly from late May to early Abraxas picaria Moore August. They are attracted to light. The wingspan is 38 mm. to picariaMoore, 1868, Proc. zool. Soc. Lond. 1893(2): 393 (Abraxas). 48 mm. The moth is nocturnal and is easy to find during the day.