The Battle for Monte Cassino a History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Truth': Representations of Intercultural 'Translations'

eScholarship California Italian Studies Title Sleights of Hand: Black Skin and Curzio Malaparte's La pelle Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0xr9d2gm Journal California Italian Studies, 3(1) Author Escolar, Marisa Publication Date 2012 DOI 10.5070/C331012084 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Sleights of Hand: Black Fingers and Curzio Malaparte’s La pelle Marisa Escolar La pelle [1949], written towards the end of Curzio Malaparte’s rather colorful political career,1 has long been used as a litmus test for its author, helping critics confirm their belief in a range of divergent and often contradictory interpretations. At one end of the spectrum is the view that he was an unscrupulous “chameleon” who distorted the reality of the Allies’ Liberation of Italy to suit his own interests.2 At the other is the claim that he was a true artist whose representations of the horrors of war absorb historical details into what is a consummately literary work.3 In other words, La pelle has been read either as a vulgar deformation or a poetic transcendence of the historical moment it purports to represent.4 And yet Malaparte’s narrative of the myriad social transformations following the Armistice actually combines concrete historical events (the Allies’ arrival in Naples and in Rome, the eruption of Vesuvius on March 22, 1944, and the battle of 1 Malaparte, born Kurt Erich Suckert, joined the Partito Nazionale Fascista in September 1922 and resigned in January, 1931 just before moving to France. Upon his return to Italy in October 1931, he was expelled from the party (despite having already left it) and sentenced to political exile on Lipari for five years of which he served less than two (Martellini Opere scelte xcii-xciv). -

“Marocchinate” Denunciano La Francia. Andrea Cionci

Le vittime delle “marocchinate” denunciano la Francia. Andrea Cionci Furono 300.000 gli stupri di donne, uomini e bambini italiani compiuti dal 1943 al ‘44 dalle truppe coloniali del Corp Expeditionnaire Français. Quella pagina si storia di riapre. Reparto di goumiers marocchini accampati Il nostro giornale lo aveva annunciato il 6 marzo scorso e l’Associazione Vittime delle Marocchinate presieduta da Emiliano Ciotti ha depositato, tramite lo studio legale dell’Avv. Luciano Randazzo, formale denuncia contro la Francia per le atrocità compiute dalle truppe coloniali francesi ai danni dei civili italiani durante l’ultima guerra. L’atto è stato presentato presso la Procure di Frosinone e Latina, presso la Procura Militare di Roma, il Comando Generale dei Carabinieri e l’Ambasciata di Francia. Furono 300.000 gli stupri di donne, uomini e bambini italiani compiuti dal 1943 al ‘44 dalle truppe coloniali del Cef (Corp Expeditionnaire Français) costituito per il 60% da marocchini, algerini e senegalesi e per il restante da francesi europei, per un totale di 111.380 uomini. A tali violenze seguirono spesso torture inimmaginabili e brutali omicidi, sia delle vittime, sia di tutti coloro che tentavano di opporvisi. Furono poi moltissimi i casi di malattie e infezioni veneree tanto da costituire una vera e propria emergenza sanitaria, come risulta dall’interpellanza parlamentare della deputata comunista Maria Maddalena Rossi dell’aprile 1952. La prime violenze si verificarono dopo lo sbarco in Sicilia, dove i magrebini del 4° tabor stuprarono donne e bambini presso Capizzi. Dopo lo sfondamento della Linea Gustav, in Ciociaria si toccò il culmine dell’aberrazione, ma le violenze proseguirono fino in Toscana. -

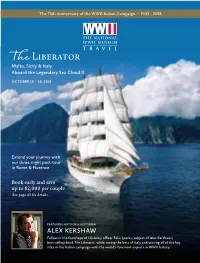

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

IL DOLORE DELLA MEMORIA Ciociaria 1943-1944

LUCIA FABI ANGELINO LOFFREDI IL DOLORE DELLA MEMORIA Ciociaria 1943-1944 1 LUCIA FABI ANGELINO LOFFREDI IL DOLORE DELLA MEMORIA Ciociaria 1943-1944 2 3 A SAMIRA 4 5 Sommario 1 L’ARMISTIZIO ..................................................................................................... 22 1.1 La BPD di Ceccano ..................................................................................................... 24 1.2 Rinasce il concetto di Patria ........................................................................................ 29 2 LA RESISTENZA ................................................................................................ 32 2.1 La Resistenza in Ciociaria ........................................................................................... 35 2.2 I due gruppi partigiani di Ceccano ................................................................................ 40 2.3 Le disavventure familiari di Romolo Battista. ................................................................ 47 3 L’ OCCUPAZIONE E LE REQUISIZIONI TEDESCHE ..................................... 53 3.1 Frosinone ................................................................................................................... 53 3.2 Patrica ........................................................................................................................ 54 3.3 Pofi ............................................................................................................................. 55 3.4 Villa Santo Stefano..................................................................................................... -

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context Andrew Sangster Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy University of East Anglia History School August 2014 Word Count: 99,919 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or abstract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis explores the life and context of Kesselring the last living German Field Marshal. It examines his background, military experience during the Great War, his involvement in the Freikorps, in order to understand what moulded his attitudes. Kesselring's role in the clandestine re-organisation of the German war machine is studied; his role in the development of the Blitzkrieg; the growth of the Luftwaffe is looked at along with his command of Air Fleets from Poland to Barbarossa. His appointment to Southern Command is explored indicating his limited authority. His command in North Africa and Italy is examined to ascertain whether he deserved the accolade of being one of the finest defence generals of the war; the thesis suggests that the Allies found this an expedient description of him which in turn masked their own inadequacies. During the final months on the Western Front, the thesis asks why he fought so ruthlessly to the bitter end. His imprisonment and trial are examined from the legal and historical/political point of view, and the contentions which arose regarding his early release. -

Advocate Winter 2016-2017 Asian American Community Celebrates Veterans Day in Nations Capital Col Bruce Hollywood, USAF (Ret)

Japanese American Veterans Association Winter 2016-2017 JAVA ADVOCATE Volume XXIV, Issue IV Inside This Issue: Veterans Day in the Capital 1 List of JAVA Officers 2 Welcome New Members 3 LCDR Osuga Moves to Tokyo 3 Ishimoto Speaks on Counterterrorism 3 2016 JAVA Memorial Scholarships 4 History of 100th & 442nd Infantry Units 6 Thank you Donors 7 Westdale Appears in 2 TV Specials 10 Postage Stamp Campaign Progress 11 Meet the Generals and Admirals 12 History: Two Recent Books 14 President Barack Obama and JAVA President COL Michael Cardarelli, Obituaries 15 USA (Ret) at the annual Veterans Day Breakfast for veteran service organizations at the White House. White House photo. Three WWII Nisei Linguists Honored 16 Asian American Community Celebrates Veterans Day in MIS Unit and Individual Awards 18 Nations Capital Fmr. Sen. Akaka Celebrates 92nd Bday 19 Col Bruce Hollywood, USAF (Ret) Michael Yaguchi Recognized 19 On a beautiful, calm, and sunny autumn afternoon, four Asian Pacific American organizations co-sponsored the 16th Annual Veterans Day NPS and JAVA Oral History Project 19 event on November 11, 2016 at the Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism in WWII, located in Washington, DC near the US Capitol. Upcoming Events 20 The four organizations were JAVA; National Japanese American Memorial Foundation (NJAMF); Pan-Pacific American Leaders and Call for Poetry Submissions 20 Mentors (PPALM); and the Japanese American Citizens League, DC Chapter (JACL). (continued on page 2…) WWW.JAVA.WILDAPRICOT.ORG JAVA Advocate Winter 2016-2017 Asian American Community Celebrates Veterans Day in Nations Capital Col Bruce Hollywood, USAF (Ret) (…continued from page 1) Major General Tony Taguba, US Army (Retired) was the keynote speaker and provided an inspirational message honoring WWII Nisei Soldiers of the 100th Infantry Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and Military Intelligence Service (MIS). -

Nato Unclassified Public Disclosed

ORGANISATION DU TRAITÉ DE L'ATLANTIQUE NORD NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY ORGANIZATION PALAIS DE CHAILLOT NATO UNCLASSIFIED P AR! S-XVl and Tel. : KLEbcr 50-20 PUBLIC DISCLOSED ORIGINAL: FRENCH NATO UNCLASSIFIED PO/ 56/1 "1 34- TOt Permanent Representatives FROM: Secretary General Resolution adopted "b.y the Steering Committee of the "Association Française pour la Communauté Atlantique" I have heen requested hy Mr. Pierre Mahias, Secretary' General of the Association Française pour la Communauté Atlantique'1, to forward to the North Atlantic Council the attached text of a resolution adopted hy the Steering Committee of that Association at a recent meeting. (Signed) ISMAY DECLASSIFIED - PUBLIC DISCLOSURE / DÉCLASSIFIÉ - MISE EN LECTURE PUBLIQUE LECTURE EN - MISE / DÉCLASSIFIÉ DISCLOSURE - PUBLIC DECLASSIFIED 11th December, 1956 ASSOCIATION FRANÇAISE POUR LA COMMUNAUTE ATLANTIQUE (Régie par la Loi de 1901) Président. : M. Georges BIDAULT comité de Patronage: MM. Jacques BARDOUX, EdwardCORNIGLION- MOLINIER, Alfred COSTE-FLORET, René COURTIN, Alphonse JUIN, Maréchal: de France, René MAYER, Antoine PINAY, Paul RAMADIER 185, rue de la Pompe Paris, 16° - KLE,.15-08 C.C.P. Paris 13.^68-58 -- L'ASSOCIATION FRAITO AI SE POUR LA COMMUNAUTE ATLANTIQUE. conscious of the serious rift which the recent crisis has produced in the Atlantic Alliance calls for the adoption of a common attitude hy member countries of the Alliance where their vital interests are concerned; . the creation of a joint executive "body responsible for defending the higher interests of -

Atti Parlamentari — 37905 — Camera Dei Deputati

Atti Parlamentari — 37905 — Camera dei Deputati XVII LEGISLATURA — ALLEGATO B AI RESOCONTI — SEDUTA DEL 20 MAGGIO 2016 628. Allegato B ATTI DI CONTROLLO E DI INDIRIZZO INDICE PAG. PAG. ATTI DI INDIRIZZO: Ottobre .................................... 4-13261 37917 Furnari ................................... 4-13264 37923 Risoluzioni in Commissione: Pini Gianluca ......................... 4-13265 37924 III Commissione: Ambiente e tutela del territorio e del mare. Di Stefano Manlio ................ 7-01002 37907 Interrogazione a risposta orale: V Commissione: Galgano ................................... 3-02272 37925 Fanucci ................................... 7-01003 37908 Interrogazioni a risposta in Commissione: VII Commissione: Carrescia ................................. 5-08737 37927 Coscia ...................................... 7-01001 37909 Burtone ................................... 5-08756 37928 XI Commissione: Interrogazione a risposta scritta: Boccuzzi ................................. 7-00999 37911 Maestri Andrea ...................... 4-13271 37929 Miccoli .................................... 7-01000 37912 Rizzetto ................................... 7-01004 37913 Beni e attività culturali e turismo. Interrogazioni a risposta scritta: ATTI DI CONTROLLO: Prodani ................................... 4-13263 37930 Presidenza del Consiglio dei ministri. Bragantini Matteo ................. 4-13267 37932 Interrogazione a risposta in Commissione: Difesa. Businarolo .............................. 5-08751 37915 Interrogazione a risposta -

US Fifth Army History

FIFTH ARMY HISTORY 5 JUNE - 15 AUGUST 1944^ FIFTH ARMY HISTORY **.***•* **• ••*..•• PART VI "Pursuit to the ^rno ************* CONFIDENTIAL t , v-.. hi Lieutenant General MARK W. CLARK . commanding CONTENTS. page CHAPTER I. CROSSING THE TIBER RIVE R ......... i A. Rome Falls to Fifth Army i B. Terrain from Rome to the Arno Ri\ er . 3 C. The Enemy Situation 6 CHAPTER II. THE PURSUIT IS ORGANIZED 9 A. Allied Strategy in Italy 9 B. Fifth Army Orders 10 C. Regrouping of Fifth Army Units 12 D. Characteristics of the Pursuit Action 14 1. Tactics of the Army 14 2. The Italian Partisans .... .. 16 CHAPTER III. SECURING THE FIRST OBJECTIVES 19 A. VI Corps Begins the Pursuit, 5-11 June 20 1. Progress along the Coast 21 2. Battles on the Inland Route 22 3. Relief of VI Corps 24 B. II Corps North of Rome, 5-10 June 25 1. The 85th Division Advances 26 2. Action of the 88th Division 28 CHAPTER IV. TO THE OMBRONE - ORCIA VALLEY .... 31 A. IV Corps on the Left, 11-20 June 32 1. Action to the Ombrone River 33 2. Clearing the Grosseto Area 36 3. Right Flank Task Force 38 B. The FEC Drive, 10-20 June 4 1 1. Advance to Highway 74 4 2 2. Gains on the Left .. 43 3. Action on the Right / • • 45 C. The Capture of Elba • • • • 4^ VII page CHAPTER V. THE ADVANCE 70 HIGHWAY 68 49 A. IV Corps along the Coast, 21 June-2 July 51 1. Last Action of the 36th Division _^_ 5 1 2. -

Two Women Is a 1960 Italian Film Directed by Vittorio De Sica. It Tells the Story of a Woman Trying to Protect Her Young Daughter from the Horrors of War

La Ciociara (1960) Two Women is a 1960 Italian film directed by Vittorio De Sica. It tells the story of a woman trying to protect her young daughter from the horrors of war. The film stars Sophia Loren, Jean- Paul Belmondo, Raf Vallone, Eleonora Brown, Carlo Ninchi, and Andrea Checchi. The film was adapted by De Sica and Cesare Zavattini from the novel of the same name written by Alberto Moravia. The story is fictional, but based on actual events of 1944 in Rome and rural Lazio, during what Italians call the Marocchinate. Loren’s performance received critical acclaim, winning her the Academy Award for Best Actress. Plot Cesira is a widowed shopkeeper, raising her devoutly religious twelve-year-old daughter, Rosetta, in Rome during World War II. In July 1943, following the Allied bombing of Rome, mother and daughter flee to Cesira’s native Ciociaria, a rural, mountainous province of central Italy. The night before they go, Cesira sleeps with Giovanni, a coal dealer in her neighbourhood, who agrees to look after her store in her absence. After they arrive at Ciociaria, Cesira attracts the attention of Michele, a young local intellectual with communist sympathies. Rosetta sees Michele as a father figure and develops a strong bond with him. Michele is later taken prisoner by German soldiers, who force him to act as a guide through the mountainous terrain. After the Allies capture Rome, in June 1944, Cesira and Rosetta decide to head back to that city. On the way, the two are gang-raped inside a church by a group of Moroccan Goumiers – soldiers attached to the invading Allied Armies in Italy. -

The Attack Will Go on the 317Th Infantry Regiment in World War Ii

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2003 The tta ack will go on the 317th Infantry Regiment in World War II Dean James Dominique Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Dominique, Dean James, "The tta ack will go on the 317th Infantry Regiment in World War II" (2003). LSU Master's Theses. 3946. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3946 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ATTACK WILL GO ON THE 317TH INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts In The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Dean James Dominique B.S., Regis University, 1997 August 2003 i ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MAPS........................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT................................................................................................................. iv INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1 -

Lunedì 7 Dicembre 2015

1 LUNEDÌ 7 DICEMBRE 2015 Ore 17:00 Chiesa di San Pietro Apostolo S. Messa Ore 17:45 Fiaccolata con l’edicola della Madonna della Pace verso la chiesa di Santa Maria Assunta. Ore 19:00 Lectio Divina sul Salmo 84, 11: “Misericordia e verità s’incontreranno, giustizia e pace si baceranno”. Relatore: Padre Gianmatteo Rogio Segretario Pontificia Facoltà Teologica Servi di Maria 2 MERCOLEDÌ 6 GENNAIO 2016 Ore 16:30 Collegiata Santa Maria Assunta CONCERTO PER LA PACE Band: The ensemble for peace 3 SABATO 9 GENNAIO 2016 Ore 16:00 (Sala del Terzo Giorno) Convegno: LA DONNA • Vergine Maria, Madre di Cristo e della Chiesa, Regina della Pace Relatore: Salvatore Perrella Preside Pontificia Facoltà Teologica Servi di Maria • Il ruolo della donna nella società moderna Relatore: Emilia Zarrilli Prefetto di Frosinone • Donna e lavoro: ancora discriminazioni? Relatore: Giulia Rodano Casa Internazionale delle Donne - Roma • Diversità e conciliazione dei ruoli Relatore: Annamaria Girolami Sindaco di Morolo 4 SABATO 18 GENNAIO 2016 / LUNEDÌ 18 APRILE 2016 CONCORSO “COSTRUIRE LA PACE É POSSIBILE” Riservato alla Scuola Primaria e Secondaria di I grado 5 SABATO 13 FEBBRAIO 2016 Ore 16:00 (Sala del Terzo Giorno) Convegno: L’ACCOGLIENZA • “Gesù, Maria e Giuseppe costretti a fuggire in Egitto minacciati dalla sete di potere di Erode” Relatore: Card. Antonio Maria Vegliò Presidente Pontificio Consiglio della Pastorale per i Migranti e gli Itineranti • “Rifiuto discriminazione, sfruttamento, dolore e morte, questa è la realtà dei migranti d’oggi” Relatore: Paolo Lojudice Vescovo Ausiliare Diocesi di Roma • Il problema dell’immigrazione: invasione o ricerca di un futuro? Relatore: Paolo Marozzo Università Urbino • La ridistribuzione della ricchezza.