The Brazilian Participation in World War II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To the Ombrone-Orcia Valley

CHAPTER IV ............... To the Ombrone-Orcia Valley r\.T noon on n June Fifth Army pursued the Germans northwestward with two fresh command groups directing operations. IV Corps was on the left and the FEC on the right after completion of their relief of VI Corps and II Corps respectively. Comparatively fresh troops were available for the continuance of the chase, especially in the French zone where the two FEC divisions initially committed, the 1st Motor ized Division and the 3d Algerian Infantry Division, had been out of heavy com bat nearly two weeks. Only one American division, the 36th, was in action on the IV Corps side. It had been following behind the swift advance of Combat Command A of the 1st Armored Division north of Rome. Although its men had been con stantly on the move since passing Rome, it had not been engaged in any extensive righting, its action behind the armor having been confined largely to mopping up operations. The 361st Regimental Combat Team was attached, giving the 36th Di vision four regimental combat teams. The 34th Division was resting in the vicinity of Tarquinia, where it had moved from Civitavecchia to make way for supply depots being set up near the port. The 1st Armored Division was rehabilitating near Bracciano, and the other two French divisions, the 26. Moroccan Infantry Division and the 4th Mountain Division, were in FEC reserve. The 85th and 88th Divisions were en route to rest areas south and west of Rome. Other American and British divisions around Rome were in the process of leaving Fifth Army. -

BRAZILIAN Military Culture

BRAZILIAN Military Culture 2018 Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy | Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center By Luis Bitencourt The FIU-USSOUTHCOM Academic Partnership Military Culture Series Florida International University’s Jack D. Gordon Institute for Public Policy (FIU-JGI) and FIU’s Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center (FIU-LACC), in collaboration with the United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM), formed the FIU-SOUTHCOM Academic Partnership. The partnership entails FIU providing research-based knowledge to further USSOUTHCOM’s understanding of the political, strategic, and cultural dimensions that shape military behavior in Latin America and the Caribbean. This goal is accomplished by employing a military culture approach. This initial phase of military culture consisted of a yearlong research program that focused on developing a standard analytical framework to identify and assess the military culture of three countries. FIU facilitated professional presentations of two countries (Cuba and Venezuela) and conducted field research for one country (Honduras). The overarching purpose of the project is two-fold: to generate a rich and dynamic base of knowledge pertaining to political, social, and strategic factors that influence military behavior; and to contribute to USSOUTHCOM’s Socio-Cultural Analysis (SCD) Program. Utilizing the notion of military culture, USSOUTHCOM has commissioned FIU-JGI to conduct country-studies in order to explain how Latin American militaries will behave in the context -

A “Brazilian Way”? Brazil's Approach to Peacebuilding

ORDER from CHAOS Foreign Policy in a Troubled World GEOECONOMICS AND GLOBAL ISSUES PAPER 5 | FEBRUARY 2017 A “Brazilian way”? Brazil’s approach to peacebuilding CHARLES T. CALL ADRIANA ERTHAL ABDENUR ABOUT THE ORDER FROM CHAOS PROJECT In the two decades following the end of the Cold War, the world experienced an era charac- terized by declining war and rising prosperity. The absence of serious geopolitical competi- tion created opportunities for increased interdependence and global cooperation. In recent years, however, several and possibly fundamental challenges to that new order have arisen— the collapse of order and the descent into violence in the Middle East; the Russian challenge to the European security order; and increasing geopolitical tensions in Asia being among the foremost of these. At this pivotal juncture, U.S. leadership is critical, and the task ahead is urgent and complex. The next U.S. president will need to adapt and protect the liberal international order as a means of continuing to provide stability and prosperity; develop a strategy that encourages cooperation not competition among willing powers; and, if neces- sary, contain or constrain actors seeking to undermine those goals. In response to these changing global dynamics, the Foreign Policy Program at Brookings has established the Order from Chaos Project. With incisive analysis, new strategies, and in- novative policies, the Foreign Policy Program and its scholars have embarked on a two-year project with three core purposes: • To analyze the dynamics in the international system that are creating stresses, challeng- es, and a breakdown of order. • To define U.S. -

Corsa Verso Le Alpi. Parte IX Cap V-3.Pdf

The enemy now seeks to delay our advance while he reassembles his broken and scattered forces in the mountains to the north. You have him against the ropes, and it now only remains for you to keep up the pressure, the relentless pursuit and enveloping tactics to prevent his escape, and to write off as completely destroyed the German armies in Italy. Now is the time for speed. Let no obstacle hold you up, since hours lost now may prolong the war for months. The enemy must be completely destroyed here. Keep relentlessly and everlastingly after him. Cut every route of escape, and final and complete victory will be yours. i. Into the Mountains. (See Map No. j.) The drive the last 6 days as Fifth Army fanned out to finish off the enemy was designed to capture as many enemy as possible in the valley and forestall the formation of the Tyrolean army reportedly being organized in the mountains. The Adige River proved no serious obstacle to our forces, and neither did the nearly unmanned defense line beyond it. The very fact that our forces could practically at will roam across country 20 miles a day indi cates clearly enough the state of the enemy organization. Nonetheless, the Germans still tried to get as many troops as they could out of the valley to the comparative safety of the Alps, and single units often fought fiercely to cover their retreat. In no case, however, did those actions constitute a real threat to the advances of our columns. Not infrequently our rear columns found places reportedly taken and cleared by leading elements again in the hands of the enemy; the simple fact was that no front lines existed, and the countryside literally swarmed with Germans from a wide variety of units, many apathetically awaiting capture and others attempting to pass unobserved through our thin lines and into the mountains. -

The Role and Importance of the Military Diplomacy in Affirming

ESCOLA DE COMANDO E ESTADO-MAIOR DO EXÉRCITO ESCOLA MARECHAL CASTELLO BRANCO Cel Art PAULO CÉSAR BESSA NEVES JÚNIOR The Role and Importance of the Military Diplomacy in affirming Brazil as a Regional Protagonist in South America (O Papel e a importância da Diplomacia Militar na afirmação do Brasil como um Protagonista Regional na América do Sul) Rio de Janeiro 2019 Col Art PAULO CÉSAR BESSA NEVES JÚNIOR The Role and Importance of the Military Diplomacy in affirming Brazil as a Regional Protagonist in South America (O Papel e a importância da Diplomacia Militar na afirmação do Brasil como um Protagonista Regional na América do Sul) Course Completion Paper presented to the Army Command and General Staff College as a partial requirement to obtain the title of Expert in Military Sciences, with emphasis on Strategic Studies. Advisor: Cel Inf WAGNER ALVES DE OLIVEIRA Rio de Janeiro 2019 N518r Neves Junior, Paulo César Bessa The role and importance of the military diplomacy in affirming Brazil as a regional protagonist in Souht America. / Paulo César Bessa Neves Júnior . 一2019. 23 fl. : il ; 30 cm. Orientação: Wagner Alves de Oliveira Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Especialização em Ciências Militares)一Escola de Comando e Estado-Maior do Exército, Rio de Janeiro, 2019. Bibliografia: fl 22-23. 1. DIPLOMACIA MILITAR. 2. AMÉRICA DO SUL. 3. BASE INDUSTRIAL DE DEFESA I. Título. CDD 372.2 Col Art PAULO CÉSAR BESSA NEVES JÚNIOR The Role and Importance of the Military Diplomacy in affirming Brazil as a Regional Protagonist in Souht America (O Papel e a importância da Diplomacia Militar na afirmação do Brasil como um Protagonista Regional na América do Sul) Course Completion Paper presented to the Army Command and General Staff College as a partial requirement to obtain the title of Expert in Military Sciences, with emphasis on Strategic Studies. -

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

Brazil's Returns from the Second World

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Auctus: The ourJ nal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Scholarship 2015 Shares of the Great War Effort: Brazil’s Returns from the Second World War Jon Tyktor Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/auctus Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons © The Author(s) Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/auctus/54 This Social Sciences is brought to you for free and open access by VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Auctus: The ourJ nal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Scholarship by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shares of the Great War Effort: Brazil’s Returns from the Second World War By Jon Tyktor Introduction The first half of the twentieth century was a period so fraught with politi- cal, military, and economic tumult that it is easy to see why several of the world’s most powerful (and some not so powerful) nations turned to totalitarian forms of governance. Indeed, nations like the United Kingdom, the United States, and (temporarily) the Republic of France, where democratic rule of law had been maintained after the 1929 Stock Market Crash, were usually the exception and not the rule. Regimes such as Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and the Estado Novo in Brazil were often established in reaction to the perceived instabilities and often deemed necessary for progress and peace. In the period leading up to the Second World War, however, the dichotomy between the ideologies of governance cre- ated two bases of international power, which provided the original basis for the Axis and Allied powers. -

Third Division World War II Vol One.Pdf

THIRD INFANTRY DIVISION THE VICTORY PATH THROUGH FRANCE AND GERMANY VOLUME ONE 'IVG. WILLIAM MOHR THE VICTORY PATH THROUGH FRANCE AND GERMANY THIRD INFANTRY DIVISION - WORLD WAR II VOLUME ONE A PICTORIAL ACCOUNT BY G. WILLIAM MOHR ABOUT THE COVER There is nothing in front of the Infantry in battle except the enemy. The Infantry leads the way to attack and bears the brunt of the enemy's attack. The primary purpose of the Infan try is to close with the enemy in hand-to-hand fighting. On the side of a house, tommy gunners of this Infantry patrol, 1st Special Service Froce Patrol, one of the many patrols that made possible the present offensive in Italy by feeling out the enemy and discovering his defensive strength, fire from the window of an adjoining building to blast Nazis out. The scene is 400 yards from the enemy lines in the Anzio area, Italy. Fifth Army, 14 April, 1944. The 3rd Infantry Division suffered 27,450 casualties and 4,922 were killed in action. 2 - Yellow Beach, Southern France, August, 1944 3 - Marseilles, France, August, 1944 4 - Montelimar, France, August, 1944 5 - Cavailair, France, August, 1944 6 - Avignon, France, August, 1944 7 - Lacroix, France, August, 1944 8 - Brignolles, France, August, 1944 9 -Aix-En-Provence, France, August, 1944 12 - St. Loup, France, August, 1944 13 - La Coucounde, France, August, 1944 14 - Les Loges Neut, France, August, 1944 15 - Besancon, France, September, 1944 18 - Loue River, Ornans, France, September, 1944 19 - Avonne, France, Septem&er, 1944 20 - Lons Le Sounier, France, September, 1944 21 - Les Belles-Baroques, France, September, 1944 22 - St. -

Introduction: the Lusophone World at War, 1914-1918 and Beyond

Introduction: The Lusophone World at War, 1914-1918 and Beyond Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses1 On March 9, 1916, Germany declared war in Portugal. In response, Lisbon sent a fighting force, the Corpo Expedicionário Português [CEP], to France, where it held a portion of the Western Front until April 9, 1918. In addition, a number of smaller expeditions were dispatched to secure Mozambique and, if possible, participate in the conquest of German East Africa. Both theatres of war were a source of frustration for the Portuguese, and participation in the conflict fell far short of the hopes deposited in it by its defenders. As interventionist politicians slowly lost control over the country’s destiny after the war’s end, the conflict faded from the public’s awareness, its memory kept alive essentially among those who had direct experience with combat. For decades, Portugal’s participation in World War I was generally ignored, or reduced to a historical cul-de-sac, a pointless, if expensive, military episode. However, our understanding of the conflict’s impact on Portugal and its importance in the subsequent course of the country’s history has increased immeasurably over the past twenty years. The centenary commemorations for both the Republic, in 2010, and the Great War itself, starting in 2014, have naturally contributed to this process. In March of 2016, on the hundredth anniversary of Portugal’s intervention in the conflict, a colloquium was held at Brown University as an attempt to insert Portugal’s war experience into a wider, but intimately related, context: that of the Lusophone world. -

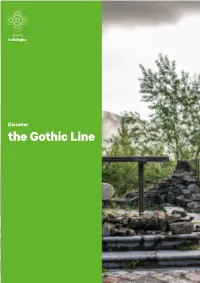

The Gothic Line

Green is Bologna Discover the Gothic Line © Martino Viviani © Martino Viviani Walking along the paths of the Gothic Line means retracing the history and the events that involved the men and women who fought in what was the last German defensive outpost during the Italian Campaign. Between October 1944 and April 1945, the Bologna Apennines were the setting of large battles between the German army and the allied forces advancing from the south of the Italian peninsula. The historic itinerary unwinds from west to east: it starts at Lake Scaffaiolo in the Corno alle Scale Regional Park and arrives in Tossignano in the Park of the Vena del Gesso Romagnolo. Milan Venice Bologna Florence Rome How to find us Bologna is easy to reach using the main means of transport. Bologna Bologna G. Marconi Airport Bologna Central Station Motorways (A1-A14) Gothic Line Trekking Lake Scaffaiolo 1st Stage: Length: 15.8 km Difference in level:+600 -1,800 Duration: 6 h Rocca Corneta 2nd Stage: Length: 14 km Difference in level:+600 -1150 Duration: 5 h Abetaia 3rd Stage: Iola Length: 15,1 km Difference in level:+500 -490 Duration: 5 h Castel d’Aiano 4th Stage: MdSpè Length: 20 km Difference in level:+750 -1,300 Duration: 7 h Vergato 5th Stage: Monte Salvaro Length: 15,6 km Difference in level:+850 -660 Duration: 6 h Monte Sole 6th Stage: Vado Length: 21 km Difference in level:+1050 -1000 Duration: 7 h Brento Livergnano 7th Stage: Monte delle Formiche Length: 16,5 km Difference in level:+1100 -1200 Duration: 6 h Monterenzio 8th Stage: Monte Cerere Length: 21 km Difference in level:+700 -800 Duration: 7 h S. -

Foreign Military Studies Office Publications

WARNING! The views expressed in FMSO publications and reports are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Guerrilla in The Brazilian Amazon by Colonel Alvaro de Souza Pinheiro, Brazilian Army commentary by Mr. William W. Mendel Foreign Military Studies Office, Fort Leavenworth, KS. July 1995 Acknowledgements The authors owe a debt of gratitude to Marcin Wiesiolek, FMSO analyst and translator, for the figures used in this study. Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey B. Demarest and Lieutenant Colonel John E. Sray, FMSO analysts, kindly assisted the authors with editing the paper. PRÉCIS Colonel Alvaro de Souza Pinheiro discusses the historical basis for Brazil's current strategic doctrine for defending the Brazilian Amazon against a number of today's transnational threats. He begins with a review of the audacious adventure of Pedro Teixeira, known in Brazilian history as "The Conqueror of the Amazon." The Teixeira expedition of 1637 discovered and manned the principle tributaries of the Amazon River, and it established an early Portuguese- Brazilian claim to the region. By the decentralized use of his forces in jungle and riverine operations, and through actions characterized by surprise against superior forces, Captain Pedro Teixeira established the Brazilian tradition of jungle warfare. These tactics have been emulated since those early times by Brazil's military leaders. Alvaro explains the use of similar operations in Brazil's 1970 counterguerrilla experience against rural Communist insurgents. The actions to suppress FOGUERA (the Araguaia Guerrilla Force, military arm of the Communist Party of Brazil) provided lessons of joint military cooperation and the integration of civilian agency resources with those of the military. -

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context Andrew Sangster Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy University of East Anglia History School August 2014 Word Count: 99,919 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or abstract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis explores the life and context of Kesselring the last living German Field Marshal. It examines his background, military experience during the Great War, his involvement in the Freikorps, in order to understand what moulded his attitudes. Kesselring's role in the clandestine re-organisation of the German war machine is studied; his role in the development of the Blitzkrieg; the growth of the Luftwaffe is looked at along with his command of Air Fleets from Poland to Barbarossa. His appointment to Southern Command is explored indicating his limited authority. His command in North Africa and Italy is examined to ascertain whether he deserved the accolade of being one of the finest defence generals of the war; the thesis suggests that the Allies found this an expedient description of him which in turn masked their own inadequacies. During the final months on the Western Front, the thesis asks why he fought so ruthlessly to the bitter end. His imprisonment and trial are examined from the legal and historical/political point of view, and the contentions which arose regarding his early release.