THE WIGAN COALFIELD in 1851 A1ONG the Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horwich Locomotive Works Conservation Area

Horwich Locomotive Works Horwich, Bolton ConservationDraft Conservation Area Management Area Management Plan Plan www.bolton.gov.uk Contents 6.0 Protecting Special Interest; 1.0 Introduction 3 Policies 18 6.1 Introduction 2.0 Summary of Special Interest 4 6.2 Buildings at risk and protection from demolition 3.0 Significant Buildings 7 6.3 Maintenance guidance 3.1 Unlisted buildings that make a 6.4 Urban design guidance for new positive contribution to the character development of the Conservation Area 6.5 Managing building alterations 3.2 Buildings and structures that are less 6.6 Protecting views and vistas significant and have a neutral impact 6.7 Open spaces and landscaping on the character of the Conservation 6.8 Monitoring change Area 6.9 Recording buildings and features 3.3 Buildings and structures that have a negative impact on the character of 7.0 Enhancement 21 the Conservation Area 7.1 Regeneration strategy 7.2 Buildings – repairs 4.0 Managing Change 13 7.3 Buildings – new uses 4.1 Horwich Locomotive Works in the 7.4 Open spaces and landscaping 21st Century – a summary of the 7.5 Linkages issues 7.6 Interpretation and community 4.2 Philosophy for change involvement 4.3 Strategic aims 8.0 The Wider Context 23 5.0 Identifying the issues that 15 Threaten the Character of the 9.0 Next Steps 24 Conservation Area 5.1 Buildings at risk, demolition and Bibliography & Acknowledgements 25 under-use 5.2 Condition of building fabric Appendices 26 5.3 Vacant sites Appendix 1: Contacts 5.4 Details – doors, windows, roofs and Appendix 2: Relevant Unitary historic fixtures Development Plan Policies 5.5 Extensions and new buildings Appendix 3: Condition audit of significant 5.6 Building services and external buildings alterations Appendix 4: 1911 plan of the works 5.7 Views and spatial form 5.8 Landscape and boundaries 5.9 Access to and around the Conservation Area Conservation Area Management Plan prepared for Bolton Council by The Architectural History Practice, June 2006. -

GMPR04 Bradford

Foreword B Contents B Bradford in East Manchester still exists as an electoral ward, yet its historical identity has waned Introduction 3 and its landscape has changed dramatically in The Natural Setting ...........................................7 recent times. The major regeneration projects that The Medieval Hall ...........................................10 created the Commonwealth Games sports complex Early Coal Mining ............................................13 and ancillary developments have transformed a The Ashton-under-Lyne Canal ........................ 17 former heavily industrialised area that had become Bradford Colliery ............................................. 19 run-down. Another transformation commenced Bradford Ironworks .........................................29 much further back in time, though, when nearly 150 The Textile Mills ..............................................35 years ago this area changed from a predominantly Life in Bradford ...............................................39 rural backwater to an industrial and residential hub The Planning Background ...............................42 of the booming city of Manchester, which in the fi rst Glossary ...........................................................44 half of the nineteenth century became the world’s Further Reading ..............................................45 leading manufacturing centre. By the 1870s, over Acknowledgements ..........................................46 15,000 people were living cheek-by-jowl with iconic symbols of the -

Soft-Bodied Fossils from the Roof Shales of the Wigan Four Foot Coal Seam, Westhoughton, Lancashire, UK

Geol. Mag. 135 (3), 1999. pp. 321-329. Printed in the United Kingdom © 1999 Cambridge University Press 321 Soft-bodied fossils from the roof shales of the Wigan Four Foot coal seam, Westhoughton, Lancashire, UK L. I. ANDERSON*, J. A. DUNLOPf, R. M. C. EAGARJ, C. A. HORROCKS§ & H. M. WILSON]] "Department of Geology and Petroleum Geology, Meston Building, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, AB24 3UE, UK tlnstitiit fiir Systematische Zoologie, Museum fiir Naturkunde, Invalidenstrasse, D-10115, Berlin, Germany ^Honorary Research Associate, The Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester, M13 9PL, UK §24 Lower Monton Road, Eccles, Manchester, M30 ONX, UK ^Department of Earth Sciences, Keele University, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK (Received 10 September 1998; accepted21 January 1999) Abstract - Exceptionally preserved fossils are described from the Westhoughton opencast coal pit near Wigan, Lancashire, UK (uppermost Westphalian A, Lower Modiolaris Chronozone, regularis faunal belt). The fossils occur within sideritic concretions in a 1.5-metre zone above the Wigan Four Foot coal seam. Arthropods dominate the fauna and include arachnids, arthropleurids, crustaceans, eurypterids, euthycarcinoids, millipedes and xiphosurans. Vertebrates are represented by a single palaeoniscid fish, numerous disarticulated scales and coprolites. Upright Sigillaria trees, massive bedded units and a general lack of trace fossils in the roof shales of the Wigan Four Foot coal seam suggest that deposi tion of the beds containing these concretions was relatively rapid. Discovery of similar faunas at the equivalent stratigraphic level some distance away point to regional rather than localized controls on exceptional preservation. Prior to Anderson et al. (1997), it was generally 1. Introduction believed that exceptionally preserved fossils in Recent investigations of new Upper Carboniferous Lancashire were restricted to the Sparth Bottoms fossil localities in the West Lancashire Coalfield have brick clay pit, Rochdale and the Soapstone bed of the produced significant results (Anderson et al. -

Jubilee Colliery, Shaw, Oldham

Jubilee Colliery, Shaw, Oldham Community-led Archaeological Investigation Oxford Archaeology North November 2014 Groundwork Oldham and Rochdale Issue No: 2014-15/1583 OA North Job No: L10748 NGR: 394310 410841 Jubilee Colliery, Shaw, Oldham: Community-led Archaeological Investigation 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................ 4 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Circumstances of Project............................................................................... 5 1.2 Location and Geology................................................................................... 6 2. METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................. 8 2.1 Aims and Objectives ..................................................................................... 8 2.2 Excavation Trenches..................................................................................... 8 2.3 Finds............................................................................................................. 8 2.4 Archive......................................................................................................... 8 3. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................................ 9 3.1 Background -

UK Coal Resource for New Exploitation Technologies Final Report

UK Coal Resource for New Exploitation Technologies Final Report Sustainable Energy & Geophysical Surveys Programme Commissioned Report CR/04/015N BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Commissioned Report CR/04/015N UK Coal Resource for New Exploitation Technologies Final Report *Jones N S, *Holloway S, +Creedy D P, +Garner K, *Smith N J P, *Browne, M.A.E. & #Durucan S. 2004. *British Geological Survey +Wardell Armstrong # Imperial College, London The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/1999 Key words Coal resources, UK, maps, undergound mining, opencast mining, coal mine methane, abandoned mine methane, coalbed methane, underground coal gasification, carbon dioxide sequestration. Front cover Cleat in coal Bibliographical reference Jones N S, Holloway S, Creedy D P, Garner K, Smith N J P, Browne, M.A.E. & Durucan S. 2004. UK Coal Resource for New Exploitation Technologies. Final Report. British Geological Survey Commissioned Report CR/04/015N. © NERC 2004 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2004 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a reference collection www.bgs.ac.uk of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA Desks. -

Astley Green Project Plan

SAVING LANCASHIRE’S MINING HERITAGE THE LANCASHIRE MINING MUSEUM @ Astley Green Colliery Page !1 HISTORY The colliery at Astley Green was begun in 1908 by the Pilkington Colliery Company, a subsidiary of the Clifton & Kersley Coal Company.The first sod was cut by Lady Pilkington and the mine opened for extraction of coal in 1912. In 1928 the colliery was amalgamated with a number of local pits to form part of the consortium called Manchester Collieries. In 1947 the coal industry was nationalised and this led to considerable modernisation of the mine. After 23 years of operation under the National Coal Board the mine was closed in 1970. It is now a museum. The monument includes the pit headgear for the number 1 shaft, the concrete thrust pillar for the 'tubbing' which supports the headgear and the steam winding engine in its original engine house for the number 1 shaft. The first shaft on the site (the number 1 shaft) was sunk in 1908. Because the ground was unstable and wet the shaft was sunk using a pioneering method known as a 'drop shaft' in which the hole is dropped using forged iron rings with a cutting shoe at the bottom of each ring. These 'tubbing' rings were forced into the underlying ground by the use of 13 hydraulic jacks braced under an iron pressure ring which was locked into the 2000 ton brick pillar which now supports the headgear.The headgear is a steel lattice construction, rivetted together, and stands 24.4 metres high. It was built by Head Wrightson of Stockton on Tees and completed in 1912. -

Coal a Chronology for Britain

BRITISH MINING No.94 COAL A CHRONOLOGY FOR BRITAIN by ALAN HILL MONOGRAPH OF THE NORTHERN MINE RESEARCH SOCIETY NOVEMBER 2012 CONTENTS Page List of illustrations 4 Acknowledgements 5 Introduction 6 Coal and the Industrial Revolution 6 The Properties of Coal 7 The constituents of coal 7 Types of Coal 8 Calorific Value 10 Proximate and ultimate analysis 10 Classification of Coal 11 By-products of Coal 12 Weights and Measures used for Coal 15 The Geology of Coal 17 The Coalfields of Great Britain 20 Scotland 20 North East England 25 Cumbria 29 Yorkshire, Lancashire and Westmorland 31 Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire 33 Lancashire and Cheshire 36 East Midlands 39 West Midlands 40 Shropshire 47 Somerset and Gloucester 50 Wales 53 Devonshire coalfield 57 Kent coalfield 57 A coal mining chronology 59 Appendix - Coal Output of Great Britain 24 8 Bibliography 25 3 Index 25 6 3 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Simplified Seyler coal chart for bituminous and anthracite coals. 12 2. The coalfields of England, Scotland and Wales. 19 3. The Scottish Coalfield between Ayr and Fife. 22 4. The Northumberland and Durham Coalfield. 27 5. The West Cumberland Coalfield showing coastal collieries. 30 6. Minor coalfields of the Askrigg Block and the Lancaster Basin. 32 7. The Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire Coalfield 34 8. The Lancashire and Cheshire Coalfield. 37 9. The Leicestershire and South Derbyshire Coalfields. 39 10. The Potteries Coalfield. 41 11. The Cannock Chase and South Staffordshire Coalfields. 43 12. The Warwickshire Coalfield. 46 13. The Shrewsbury, Coalbrookdale, Wyre Forest and Clee Hills Coalfields. -

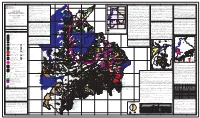

Mineral Resources Map for Lancashire

10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 904 00000 10 20 30 40 Topography reproduced from the OS map by British Geological Survey with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of The BGS maps covering Lancashire, Blackburn with Darwen and Blackpool CRUSHED ROCK AGGREGATES BUILDING STONE BRICK CLAY (including FIRECLAY) Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence A variety of hard rocks are, when crushed, suitable for use as aggregates. Their technical suitability for different applications depends on Historically, Lancashire has a very long tradition of using locally quarried stone for building purposes. The oldest rocks of the county are 'Brick clay' is the term used to describe clay used predominantly in the manufacture of bricks and, to a lesser extent, roof tiles, clay number: 100037272 2006. 49 50 their physical characteristics, such as crushing strength and resistance to impact and abrasion. Higher quality aggregates are required the limestones of the Lower Carboniferous succession and these have been quarried locally along much of their outcrop, notably around pipes and decorative pottery. These clays may also be used in cement manufacture, as a source of constructional fill and for lining and for coating with bitumen for road surfacing, or for mixing with cement to produce concrete. For applications such as constructional fill Carnforth and Clitheroe. sealing landfill sites. The suitability of a clay for the manufacture of bricks depends principally on its behaviour during shaping, drying 80 Digital SSSI, NNR, SAC, SPA and RAMSAR boundaries © English Nature 2004. -

Mineral Resources Map for Merseyside

90 300000 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 400000 BGS maps covering Liverpool, Knowsley, Sefton, St. Helens and Wirral 450 2 74 Inactive or unproductive Deep coal at more than 1200 m coalfield Petroleum Exploration and Shallow coal with less than PEDL Development Licence issued 50 m overburden under the Petroleum (Production) Act 1934 (as at Nov. 2005) Deep coal between 50 m MERSEYSIDE FORMBY G13 and 1200 m Hydrocarbon well (comprising City of Liverpool, Boroughs of 83 30 84 30 Knowsley, Sefton, St. Helens and Wirral) FORMBY 5 FRESHFIELD G2 Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, FRESHFIELD G1 FORMBY G38 FORMBY 6 FORMBY G37 FORMBY G46 Regional and Local Planning FORMBY G102 FORMBY 4 Mineral Resources FORMBY G59 FORMBY G101/101A Scale 1:100 000 SEFTON FLEA MOSS G2 PEDL134 FLEA MOSS G1 FORMBY G22 MUSTANG LITTLE CROSBY ST. HELENS 400 EXL273 PEDL101 GREENPARK 96 97 MUSTANG KNOWSLEY CROXTETH 2 2 2 3 LIVERPOOL Ribble Estuary CROXTETH 1 Foreshore (SiS) (Southport Shore) (SiS) EXL253 WIRRAL EASTERN/PEG EXL273 20 GREENPARK 20 PEDL116 STRATAGAS PEDL145 ISLAND GAS 425 450 EXL276 PEDL038 BIOGAS Production of this map was commissioned and funded by the Office of the ALKANE Deputy Prime Minister (Contract MP0677). PEDL038 ALKANE 1:63 360 or 1:50 000 map published Current digital availability of these sheets can be found on the British Geological Survey website: www.bgs.ac.uk SAND & GRAVEL 450 Superficial deposits Sub-alluvial: Inferred resources Glaciofluvial deposits PEAT 400 400 10 10 BRICK CLAY Carboniferous Brick clay and Fireclay coincident -

The Tunnels of Wet Earth

WET EARTH COLLIERY SCRAPBOOK. Compiled by Dave Lane. This publication may be printed out free of charge for your own personal use. Any use of the contents for financial gain is strictly prohibited. Edition 2. January 2003 Introduction. For many years I have waited for someone to write a book about the colliery of Wet Earth at Clifton , near Manchester. As no book has so far materialised yet people are always asking for more details about the mine, I have put together this brief collection of articles, information sheets and photographs to satisfy both myself and others who are interested both in the colliery and the general area. This scrapbook has been produced only for my own interest and will not be “published” in any proper sense of this word, although I may run off a few copies for friends and the odd person who has expressed interest. A copy of it will be placed on the Internet. The scrapbook is NOT a “book” about Wet Earth. One hopes that such a volume may eventually materialise - authored by someone who knows a lot more than I do about the subject - and who is better at writing! In the meantime, just dip into this publication! Although parts of this book have been written by the compiler, a great deal of material is merely extracts from the work of others. Credit has been given to the writers if known. Extracts have also been taken from the Information boards which used to exist all around the site (but which have been repeatedly vandalised and now no longer exist) and also from some information sheets I have come across. -

The History of Astley Green Colliery

The History Of Astley Green Colliery J.G.Isherwood 9/9/1990 The History of the Astley Green Colliery (Writing in 1990) Introduction The Astley Green Colliery was situated 3 miles east of Leigh and 8 miles west of Manchester, about 500 yards to the South of the East Lancashire Road. Today all that can be seen of this once thriving concern is the Engine House of its No.1 Shaft, the Shaft Headgear, and two other buildings. Visitors to the site often look around and say "Why - was there a colliery here ?" so effective has been the land reclamation. It is only through good fortune that anything remains at all. For Astley has some claims to fame, the remaining engine house contains what was and now is one of the largest steam winding engines ever to have been installed in this country - and certainly the largest built and erected in Lancashire. At the eleventh hour when the colliery closed in 1970 and the demolition contractors moved in, far sighted officials in Manchester and Wigan managed to get the N.C.B. to leave the engine alone along with its headgear and outbuildings. Unfortunately at the time, apart from boarding up the windows that was all that was done and so the engine remained locked away, prey to vandals and the weather alike until some ten years later a group of steam engine enthusiasts were given permission to move onto the site in the hope that eventually a heritage museum of some kind might be developed on the site, around the old pit head. -

Radcliffe Heritage Project Volunteer Research

Radcliffe Heritage Project Volunteer Research The Geology and Stratigraphy of Radcliffe Tower and the Surrounding Area Draft Version 1 Client: Bury Council Technical Report: Samantha Mayo Report No: 17/2014 © CfAA: Radcliffe Heritage Project Volunteer Research: The geology of the Tower 2014 (17) 1 Contents 1. The Geology and Stratigraphy of Radcliffe 3 2. The Geology of Radcliffe Tower 4 3. Possible Sources of the Building Stone 5 4. Conclusion 6 5. Sources 7 Illustrations 8 © CfAA: Radcliffe Heritage Project Volunteer Research: The geology of the Tower 2014 (17) 2 1. The Geology and Stratigraphy of Radcliffe The area of Radcliffe, like much of northwest England, is sited upon late Carboniferous, Pennine middle coal measures as a part of the Lancashire coalfield complex. While there are some outcrops of exposed coal seams, much of the coal measure itself, including parts of the Radcliffe area, is overlain by sedimentary rock. These upper sedimentary rock layers are commonly composed of sand, clay and gravel deposits from quaternary glaciation. Radcliffe town is situated within the Irwell valley area, north of the river Irwell, lying where the stratigraphy alters to thick beds of red sandstone. It is this distinctive colouring that is visible on exposed outcrops, opposite the town on the banks of the river Irwell, which supposedly contributed to the name Radcliffe, meaning Red Cliffs. © CfAA: Radcliffe Heritage Project Volunteer Research: The geology of the Tower 2014 (17) 3 2. The Geology of Radcliffe Tower Radcliffe tower itself comprises of many different rock types, with stones cut in varying sizes, from various stages of repair and alterations, such as the infilling of the doorways.