Food Production, Processing and Distribution in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uk Licensed Products Nov 2020

UK LICENSED PRODUCTS NOV 2020 Product Brand Product Name Company number Alara Wholefoods Alara Wholefoods OATS-GB-001-009 Organic Gluten Free Scottish Oats Porridge Ltd Green's Beers GB-004-001 Discovery Greens Beers Green's Beers GB-004-002 Dry Hopped Lager Green's Beers GB-004-003 Pilsner Green's Beers GB-004-004 Golden Ale Green's Beers GB-004-005 Blond Green's GB-004-007 Dark Ale Green's Beers GB-004-007 Dark Green's Beers GB-004-008 India Pale Ale Green's Beers GB-004-009 Tripel Green's Beers GB-004-010 Dubbel Lovemore GB-006-002 Apple and Sultana cookies x2 Welsh Hills Bakery Lovemore GB-006-005 Chocolate Brownie Slices x2 Lovemore GB-006-006 Chocolate Brownie Slice Lovemore GB-006-007 Chocolate Chip Cookies Lovemore GB-006-008 Chocolate Chip Cookies Lovemore GB-006-010 Deep Filled Mince Pies Lovemore GB-006-011 Digestive Biscuits Lovemore GB-006-014 Gingerbread Men Lovemore GB-006-017 Lemon Cake Slices Lovemore GB-006-018 Fruit Cake mini slice Lovemore GB-006-019 Fruit Cake Slices Lovemore GB-006-021 Apple Pies Lovemore GB-006-022 Cherry Bakewells Lovemore GB-006-023 Chocolate Celebration Cake Lovemore GB-006-024 Chocolate Muffins Lovemore GB-006-025 Crispbreads Lovemore GB-006-026 Custard Creams Lovemore GB-006-027 Double Chocolate Cookies Lovemore GB-006-028 Jammy Wheels Lovemore GB-006-029 Chocolate Cake mini slice Lovemore GB-006-030 Madeira Cake mini slice Lovemore OATS-GB-006-031 Oat Crunch Cookies Lovemore GB-006-032 O'Chocos Lovemore GB-006-033 Shortbread Fingers Welsh Hills Bakery GB-006-034 Dundee Welsh Hills Bakery GB-006-036 -

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 20 July 2017 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:34 P.M., 20 July 2017). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 10 Social Tariffs: Torfaen 19 ATTORNEY GENERAL 10 Taxation: Electronic Hate Crime: Prosecutions 10 Government 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Technology and Innovation INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 10 Centres 20 Business: Broadband 10 UK Consumer Product Recall Review 20 Construction: Employment 11 Voluntary Work: Leave 21 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: CABINET OFFICE 21 Mass Media 11 Brexit 21 Department for Business, Elections: Subversion 21 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Electoral Register 22 Staff 11 Government Departments: Directors: Equality 12 Procurement 22 Domestic Appliances: Safety 13 Intimidation of Parliamentary Economic Growth: Candidates Review 22 Environment Protection 13 Living Wage: Jarrow 23 Electrical Safety: Testing 14 New Businesses: Newham 23 Fracking 14 Personal Income 23 Insolvency 14 Public Sector: Blaenau Gwent 24 Iron and Steel: Procurement 17 Public Sector: Cardiff Central 24 Mergers and Monopolies: Data Public Sector: Ogmore 24 Protection 17 Public Sector: Swansea East 24 Nuclear Power: Treaties 18 Public Sector: Torfaen 25 Offshore Industry: North Sea 18 Public Sector: Wrexham 25 Performing Arts 18 Young People: Cardiff Central -

Plymouth to Bude 12 Via Saltash | St Melllion | Callington | Stoke Climsland | Launceston | Whitstone

Plymouth to Bude 12 via Saltash | St Melllion | Callington | Stoke Climsland | Launceston | Whitstone Mondays to Saturdays except bank holidays Plymouth Royal Parade A7 0500 0600 0610 0700 0740 0800 0900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1400 1500 1520* 1605 1705 1805 1910 2110 2310 Railway Station Saltash Road 0504 0604 0614 0704 0744 0804 0904 1004 1104 1204 1304 1404 1404 1504 1609 1709 1809 1914 2114 2313 Milehouse Alma Road 0507 0607 0617 0707 0747 0807 0907 1007 1107 1207 1307 1407 1407 1507 1612 1712 1812 1917 2117 2316 St Budeaux Square SB1 0514 0614 0626 0716 0756 0816 0916 1016 1116 1216 1316 1416 1416 1516 1621 1721 1821 1924 2124 2321 Saltash Fore Street 0519 0619 0631 0721 0801 0821 0921 1021 1121 1221 1321 1421 1421 1521 1626 1726 1826 1929 2129 2326 Broad Walk Saltash School 0805 1510 Cornwall College Church Road 0807 1513 34 Callington Road shops 0522 0622 0634 0724 0809 0824 0924 1024 1124 1224 1324 1424 1424 1515 1524 1629 1729 1829 1932 2132 2329 Gilston Road Junction 0524 0624 0636 0726 0811 0826 0926 1026 1126 1226 1326 1426 1426 1517 1526 1631 1731 1831 1934 2134 2330 Carkeel Dirty Lane 0527 0627 0640 0730 0815 0830 0930 1030 1130 1230 1330 1430 1430 1521 1530 1635 1735 1835 1937 2137 2332 Hatt Bus Shelter 0530 0630 0644 0734 0819 0834 0934 1034 1134 1234 1334 1434 1434 1525 1534 1639 1739 1839 1940 2140 2334 St Mellion Coryton Arms 0535 0635 0649 0739 0824 0839 0939 1039 1139 1239 1339 1439 1439 1539 1644 1744 1844 1945 2145 2339 Tavistock Road opp Ginsters 0542 0642 Callington New Road arr 0545 0645 0656 0746 0831 0846 -

SHLAA2 Report Draft

Cornwall Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment Cornwall Council February 2015 1 Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................... 4 1.1 Background ................................................................................. 4 1.2 Study Area .................................................................................. 4 1.3 Purpose of this Report ................................................................... 5 1.4 Structure of the Report ................................................................. 6 2. Planning Policy Context ...................................................................... 7 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................. 7 2.2 National Planning Policy Framework (2012) ..................................... 7 2.3 Emerging Cornwall Local Plan ......................................................... 8 2.4 Determining Cornwall’s Housing Need ........................................... 10 2.5 Determining the Buffer for Non-Delivery ........................................ 11 2.6 Summary .................................................................................. 12 3. Methodology ................................................................................... 13 3.1 Introduction ............................................................................... 13 3.2 Baseline Date ............................................................................. 13 3.3 A Partnership -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local

Title: CIoS Local Enterprise Partnership Board Date: Wednesday 28 July 2021 Time: 10.00 to 13.00 Venue: : - Council Offices, Chy Trevail, Bodmin, PL31 2FR Livestream Link: https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup- join/19%3ameeting_NmFkNzY4NWMtNmVjMy00YTgxLWFhZTMtMDZlZDRlZGIyNTU5 %40thread.v2/0?context=%7b%22Tid%22%3a%22efaa16aa-d1de-4d58-ba2e- 2833fdfdd29f%22%2c%22Oid%22%3a%22fa9d3751-6eb5-4308-b8c3- 006db67ed9ac%22%2c%22IsBroadcastMeeting%22%3atrue%7d&btype=a&role=a Agenda Item Lead Action 1. 10.00 Welcome and Introductions Apologies for Absence Directors: Louis Mathers Officers: Phil Mason, John Curnow 2. 10.05 Declarations of Interest ALL 3. 10.10 LEP Board (31 March 2021) 3 .1 Minutes (Pages 3 - 11) MD To note 3 .2 Action Summary (Page 12) GCG To note 4. Strategic Matters 4 .1 10.20 Chair Update MD To note 4 .2 10.30 CEO Report, with a focus on: (Pages 13 - 65) GCG To note/ Labour market and skills challenges presentation Green Industrial Revolution 4 .3 11.25 Fishing Sector Update (Pages 66 - 68) MD/NC Decision Page 1 4 .4 11.50 Nominations Committee Update (Pages 69 - GCG Decision 122) 4 .5 12.15 Audit & Assurance Committee Update (Pages GCG Decision 123 - 198) 4 .6 12.25 Enterprise Zones Board Update (Pages 199 - SJ/GCG To note 202) 4 .7 12.35 Any other business 5. Exclusion of Press and Public 5 .1 12.40 Investment & Oversight Panel Update (Pages MD/GCG To note 203 - 206) 5 .2 12.50 Any other confidential business ALL Page 2 Agenda No. 3.1 Information Classification: CONTROLLED CORNWALL AND ISLES OF SCILLY LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP MINUTES of a Meeting of the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership held in the Online - Virtual Meeting on Wednesday 31 March 2021 commencing at 10.00 am. -

Lezant Parish Magazine Issue 120 April 2020

LEZANT PARISH MAGAZINE ISSUE 120 APRIL 2020 EDITORS: JILL, JO AND ROB TEL 01579 370835, 01579 371073, 01579 370151 EMAIL: [email protected] ADVERTISING and ACCOUNTS: Pam West TEL 01579 371167 EMAIL: [email protected] DISTRIBUTION: Jill Price TEL 01579 370835 EMAIL:[email protected] Trekenner School’s Songfest group 2020 We are now on Facebook, search Lezant Parish Magazine 36 Welcome to the Lezant Parish Magazine for April. It is my pleasure to join the LIST OF ADVERTISERS editorial team —please bear with me; I am sure there will be some errors as I Page find my feet. Do you recognize the person on the front page? Ed Rowe aka Ker- ACORN EQUINE RUG WASH 34 now King visited Trekenner School during March. He brought along a replica of A J DESIGN (Andy Paton) Chartered Architectural Technician 22 Cornish mining engineer Richard Trevithick‘s Puffin Devil locomotive. You can A N JEWELL Painter and Decorator 23 read more about it on page 19. My family moved to the Parish five years ago and CBL STOVE & CHIMNEY SPECIALISTS 25 although I grew up near Launceston I am very much in my infancy when it comes C L BUILDING SERVICES 13 to Cornish history, particularly our local history. The LPAG are doing great work ESG BOILERCARE 12 in formalizing much of our local history and are about to begin recording oral GLEBE VETERINARY SURGERY 26 history for future generations, see their report on page 21. GROUP TRAVEL Coach Hire and Excursions 29 Speaking of past and present, the future of this magazine is in the hands of the JACQUELINE DONAHUE Beauty and Cosmetic Clinic 23 residents of the parish and in order for it to continue we really need another JOHN CLARK Carpentry/Painting/Decorating 22 person to join the editorial team. -

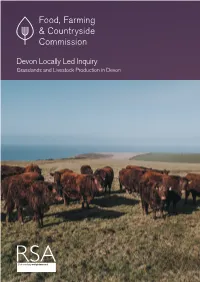

Devon Locally Led Inquiry Grasslands and Livestock Production in Devon Contents

Devon Locally Led Inquiry Grasslands and Livestock Production in Devon Contents Preface 3 Key messages 4 Introduction 5 Flying the flag for grass 6 Grasslands’ contribution to agriculture 8 Agriculture in the regional economy 10 Nutrition related to grass-based livestock production 12 Climate-related complexities 14 Recommendations 17 References 18 Thanks The RSA Food, Farming and Countryside Commission would like to thank: Beth Dooley and Matt Lobley for their invaluable work enabling the working groups turn their research ideas into action; David Fursdon for chairing the Devon Committee so ably; Members of the Committee for their generosity in volunteering their time and expertise: Andrew Butler, Elaine Cook, Kevin Cox, Stephen Criddle, Keri Denton, Tim Dudgeon, Henri Greig, Peter Greig, Catherine Mead, Richard Pocock, Mary Quicke, Mel Squires, and the many additional stakeholders who shared their insights and networks. Preface Launched in November 2017, the RSA Food, from Devon and neighbouring Cornwall. This Farming and Countryside Commission is a major, Committee identified four key issues: Health and two-year independent inquiry, funded by Esmée Thriving Communities; New Entrants; Devon’s Fairbairn Foundation. Grasslands, and Environment and Biodiversity. Each of these were explored by their own working Chaired by Sir Ian Cheshire, with fourteen group, chaired by a member of the Committee. Commissioners from across sectors, the Work took place between June 2018 and May Commission is tasked with creating mandate for 2019. change across our food system, farming sector The Devon Committee were ably assisted by and in rural communities; shaping a long term Professor Matt Lobley and Beth Dooley from the vision for the future that’s fairer, stands the test University of Exeter who acted as lead researchers of time and aligns more closely with changing and authors. -

March 2011 at 7.0Pm and Thereafter on the Following 5 Thursdays 17Th., 24Th

Your free magazine—please take one Springtime and Lent THE MYLOR MAGAZINE , MARCH, 2011 A magazine for Church and Community The Mylor Magazine [email protected] Published by: The PCC of St Mylor and All Saints Editor: Revd. Roger Nicholls 01326 374408 Production & Design: David Eastburn 01326 374237 John Clark 01872 865974 Community & Advertising : Val Jeans-Jakobsson 01326 374767 Photography : Geoff Adams 01326 374197 Finance: Ruth Bray Proofing & PCC: Judy Menage Printing: Good Impressions, Redruth 01209 314451 Deadline dates for Copy for 2011 April — March 12th May - April 16th June - May 14th Advertising in the Parish Magazine Rates — per issue (artwork supplied) Full page (A5) £15.00 Half page £9.00 Quarter page £5.00 E-mail: [email protected] for further details 2 Parish of St Mylor with the Mission Church of All Saints Church Mylor Bridge Services for March, 2011 Regular services Sundays 8am Holy Communion, 1662, St Mylor. 9am Holy Communion, CW, All Saints 10.30am Parish Eucharist, St Mylor 4pm BCP Evening Prayer , All Saints Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays 9am Morning Prayer, All Saints, Mylor Bridge Wednesdays Holy Communion, 10 am, St Mylor—11 am, All Saints Diary for March Tue 1 Women’s Fellowship. (MMC 2:00 pm) Mrs Morwenna Bennett Wed 2 Local History Group AGM (TH 7:30pm) All welcome Fri 4 Women’s World Day of Prayer (AS 2:30) Mon 7 Mylor Flower Club (OS 7:30) Let’s Move On Mrs Diane Bate Friends of St Mylor AGM (AS 7:30) Thu 10 Lent Course (St Peter’s, Flushing 7:00) Soul Spark Angela Brown Mon 14 Mylor Gardening Club (OS 7:30) Greek Islands’ Plants Trevor Wiltshire Tue 15 Women’s Fellowship. -

Underactive Thyroid

Underactive Thyroid PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 21 Jun 2012 14:27:58 UTC Contents Articles Thyroid 1 Hypothyroidism 14 Nutrition 22 B vitamins 47 Vitamin E 53 Iodine 60 Selenium 75 Omega-6 fatty acid 90 Borage 94 Tyrosine 97 Phytotherapy 103 Fucus vesiculosus 107 Commiphora wightii 110 Nori 112 Desiccated thyroid extract 116 References Article Sources and Contributors 121 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 124 Article Licenses License 126 Thyroid 1 Thyroid thyroid Thyroid and parathyroid. Latin glandula thyroidea [1] Gray's subject #272 1269 System Endocrine system Precursor Thyroid diverticulum (an extension of endoderm into 2nd Branchial arch) [2] MeSH Thyroid+Gland [3] Dorlands/Elsevier Thyroid gland The thyroid gland or simply, the thyroid /ˈθaɪrɔɪd/, in vertebrate anatomy, is one of the largest endocrine glands. The thyroid gland is found in the neck, below the thyroid cartilage (which forms the laryngeal prominence, or "Adam's apple"). The isthmus (the bridge between the two lobes of the thyroid) is located inferior to the cricoid cartilage. The thyroid gland controls how quickly the body uses energy, makes proteins, and controls how sensitive the body is to other hormones. It participates in these processes by producing thyroid hormones, the principal ones being triiodothyronine (T ) and thyroxine which can sometimes be referred to as tetraiodothyronine (T ). These hormones 3 4 regulate the rate of metabolism and affect the growth and rate of function of many other systems in the body. T and 3 T are synthesized from both iodine and tyrosine. -

Psychological Science

Psychological Science http://pss.sagepub.com/ Sensory-Specific Satiety Is Intact in Amnesics Who Eat Multiple Meals Suzanne Higgs, Amy C. Williamson, Pia Rotshtein and Glyn W. Humphreys Psychological Science 2008 19: 623 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02132.x The online version of this article can be found at: http://pss.sagepub.com/content/19/7/623 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Association for Psychological Science Additional services and information for Psychological Science can be found at: Email Alerts: http://pss.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://pss.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com at University of Aberdeen on August 24, 2010 PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Report Sensory-Specific Satiety Is Intact in Amnesics Who Eat Multiple Meals Suzanne Higgs, Amy C. Williamson, Pia Rotshtein, and Glyn W. Humphreys University of Birmingham ABSTRACT—What is the relationship between memory and Despite these intriguing findings, little is known about the appetite? We explored this question by examining prefer- mechanisms underlying multiple-meal eating in amnesia. ences for recently consumed food in patients with amnesia. Because the procedure in previous studies has been to offer the Although the patients were unable to remember having same meals in succession, one explanation is that the usual eaten, and were inclined to eat multiple meals, we found decline in palatability and intake of a food that has been eaten to that sensory-specific satiety was intact in these patients. satiety is disrupted in amnesia (Rolls, Rolls, Rowe, & Sweeney, The data suggest that sensory-specific satiety can occur in 1973). -

Freshpoint-Select-2019-Edition-1.Pdf

Contents Dairy Fresh Cornish Milk & Alpro Page 3 Cornish Clotted Cream & Liquid Cream Page 4 Crème Fraiche & Other Creams Page 5 Butter & Spreads Page 5 Cornish Cheese Page 6 British & Continental Cheese Page 7 Yogurts Page 8 Fresh & Liquid Eggs Page 9 Fruit Juices Page 9 Bakery Hovis Page 10 Prima Bakery Pasties Page 10 Handmade Bread & Sliced Bread Page 11 Grocery Tomatoes, Baked Beans & Peas Page 12 Peppers, Pesto & Olives Page 12 Oils & Vinegars Page 13 Rice, Pasta, Pulses & Grains Page 14 Mushrooms, Mustard, Mayo & More Page 14 Sugar, Flour & Baking Essentials Page 15 Sea Salt, Seaweed, Seasoning & Sea Peppers Page 16 Jam, Marmalade & Honey Page 17 Tea Page 18 Cooking Wines, Spirits & Cider Page 18 Biscuits & Confectionery Page 19 Drinks Cornish Wines & Spirits Page 21 Hampers The Cornwall Hamper Company Page 22 Prices are correct at time of publication but are subject to change without notice FreshPoint Select – 2019 – Edition 1 2 Cornish Milk Cornish Semi-Skimmed Milk 500ml 39p 1 litre 59p 2 litre 99p 13.5 litre pergal £6.99 Cornish Skimmed Milk 500ml 39p 1 litre 59p 2 litre 99p Cornish Whole Milk 500ml 39p 1 litre 59p 2 litre 99p 13.5 litre pergal £6.99 Trewithen Dairy Buttermilk is much sought-after by bakers and caterers. It’s not just a perfect base for delicious pastries and sweets, it helps give a lighter texture to scones. Buttermilk 2 litre £3.75 Non-Dairy Alternative Alpro Almond Original 1 litre £1.39 8 x 1 litre £10.50 Alpro Coconut 1 litre £1.39 8 x 1 litre £10.50 Alpro Professional Soya 1 litre £1.09 12 x 1 litre £12.49 Alpro Rice 1 litre £1.30 8 x 1 litre £10.50 FreshPoint Select – 2019 – Edition 1 3 Cornish Clotted & Liquid Creams ** Pre-order by 2pm for Next Day Delivery** Rodda’s Cornish Clotted Cream 56g (2oz) ** £0.51 113g (4oz) ** £0.84 227g (8oz) £1.59 453g (1lb) ** £3.15 907g (2lb) £6.19 80 x 56g portions ** £35.09 48 x 40g portions ** £15.90 Rodda’s Liquid Cream Rodda’s Double Cream 2 litre ** £7.99 Rodda’s Single Cream 2 litre ** £6.49 Rodda’s Whipping Cream 2 litre ** £7.19 +++ Pre-order by 2pm on Day 1 for Delivery on Day 3 e.g. -

TJ's Traditional Christmas Pudding Lemon Posset Rich Chocolate Box

Tommy’s crab bisque Roasted cornish turkey with brandy cream & croutons Slow roasted cornish turkey Roast potatoes, parsnip puree, TJ’s traditional Christmas pudding Flash fried cold smoked chantenay carrots, roasted chestnuts, with brandy cream and sugar topping venison loin pigs in blanket & stuffing with honey roasted parsnip & orzo pasta Lemon posset Sous vide sirloin of beef Pressed chicken & artichoke Chateau potatoes, cornish pudding, Rich chocolate box terrine watercress, cauliflower & chantenay carrots Cornish cheese board Goats cheese pannacotta Cornish blue, cornish yarg and with beetroot carpaccio Chorizo encrusted monkfish davidstow cheddar Ratta potatoes, leek and samphire polenta & cherry vine tomatoes FINISH WITH COFFEE AND Quince and apple sorbet PETIT FOURS Homemade sautéed potato BOOK YOUR TABLE TODAY: gnocchi Celeriac & apple puree with baby turnip TO BOOK YOUR TABLE SIMPLY CALL 01288 356013 5th, 6th, 12th, 13th, 19th, 20th December TJ’s slow roasted tomato soup Roasted cornish turkey TJ’s Christmas pudding with Basil, crème fraiche & ciabatta croutons Roast potatoes, seasonal vegetables brandy sauce & roast gravy Homemade chicken liver pate Hazelnut parfait with shortbread Wrapped in prosciutto crudo, served Roasted cod fillet biscuit with port wine jelly & walnut bread Paella risotto, prawns, mussels & watercress Cornish cheese board - Melted red onion filo tart Cornish blue, yarg and davidstow Baked goats cheese, balsamic shallots Savoury pancakes cheddar served with celery, grapes Ratatouille, herbed cream cheese, and crackers tomato sauce FINISH WITH COFFEE AND PETIT FOURS Christmas Party - room rates £55 Standard Double/£62 Superior Double/£70 Luxury/Family. All rates based on 2 people sharing & include breakfast Tommy Jacks Beach Hotel, Crooklets Beach, Bude, Cornwall, EX23 8NF T.