Bill Guest STELLA AURORAE: the HISTORY of a SOUTH AFRICAN UNIVERSITY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIPE-002633.Pdf

.0 . EDmON SOUTH AFRICA. CATEWA.YOr TIlE C""trI'& 0' t;OO1J Hon SOUTH AFRICA (THE CAPE COLONY, NATAL, ORANGE FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICAN . REPPBLIG, RHODESIA, AND ALL OTHER TERRITORIES SOUTH OF THE ZAMBESI) BY GEORGE M'CALL THEAL, D.Lrf., LL.D. NINTH IMPRESSION (SIXTH EDITION) 1on~on T. FISHER UNWIN PATBa.NOS1"Sa. SQUAIS COPVRJ(;HT BY T. FISHER UNWIN, 1894 (For Great Britain). CopfiRlGHT BY G. P. PUTNAM'S, 1894 (For the United Stal~ of America) Vb] (~ PREFACE TO FIFTH EDITION. THE chapters in this volume upon the Cape Colony before 1848, Natal before 1845, and the Orange Free State, South African Republic, Zulu land, and Basutoland before 1872, contain an outline of my History of South Africa, which has been published in -England in five octavo volumes. In that work my authorities are given, so they need not be repeated here. The remaining c~apters have been written merely from general acquaintance with South African affairs acquired during many years' residence -in the country, and have not the same claim to be regarded as absolutely correct, though I have endeavoured to make them reliable. In prep,!ring the book I was guided by the principle that truth should tie told, regardless of nationalities or parties, and I strove to the utmost. to avoid anything like favour or prejudice. The above was the preface to the first edition of this book, which was __ puJ:>lished in September, 1893. As successive edition!;" aRB"ared the volume was enlarged, and nov: it has been my task to add the saddest chapter of the whole, the one in which is recorded the bc~inning. -

Click Here to Download

The Project Gutenberg EBook of South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I, by J. Castell Hopkins and Murat Halstead This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I Comprising a History of South Africa and its people, including the war of 1899 and 1900 Author: J. Castell Hopkins Murat Halstead Release Date: December 1, 2012 [EBook #41521] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SOUTH AFRICA AND BOER-BRITISH WAR *** Produced by Al Haines JOSEPH CHAMBERLAIN, Colonial Secretary of England. PAUL KRUGER, President of the South African Republic. (Photo from Duffus Bros.) South Africa AND The Boer-British War COMPRISING A HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA AND ITS PEOPLE, INCLUDING THE WAR OF 1899 AND 1900 BY J. CASTELL HOPKINS, F.S.S. Author of The Life and Works of Mr. Gladstone; Queen Victoria, Her Life and Reign; The Sword of Islam, or Annals of Turkish Power; Life and Work of Sir John Thompson. Editor of "Canada; An Encyclopedia," in six volumes. AND MURAT HALSTEAD Formerly Editor of the Cincinnati "Commercial Gazette," and the Brooklyn "Standard-Union." Author of The Story of Cuba; Life of William McKinley; The Story of the Philippines; The History of American Expansion; The History of the Spanish-American War; Our New Possessions, and The Life and Achievements of Admiral Dewey, etc., etc. -

The DHS Herald

The DHS Herald 23 February 2019 Durban High School Issue 07/2019 Head Master : Mr A D Pinheiro Our Busy School! It has been a busy week for a 50m pool, we have been asked School, with another one coming to host the gala here at DHS. up next week as we move from the summer sport fixtures to the This is an honour and we look winter sport fixtures. forward to welcoming the traditional boys’ schools in Durban This week our Grade 9 boys to our beautiful facility on attended their Outdoor Leadership Wednesday 27 February. The Gala excursion at Spirit of Adventure, starts at 4pm. Shongweni Dam. They had a great deal of fun, thoroughly enjoying Schools participating are: their adventure away from home, Contents participating in a wide range of Westville Boys’ High School activities. A full report will be in Kearsney College Our Busy School! 1 next week’s Herald. Clifton College Sport Results 2 Glenwood High School Weeks Ahead 3 The Chess boys left early Thursday Northwood School This Weekend’s Fixtures 3 morning for Bloemfontein to Durban High School participate in the Grey College MySchool 3 Chess Tournament. This is a The Gala is to be live-streamed by D&D Gala @ DHS 4 prestigious tournament, with 16 of DHS TV, so you can catch all the Rugby Fixtures 2019 4 our boys from Grades 10 to 12 action live if you are not able to competing against 22 schools from attend. Go to www.digitv.co.za to around the country. A full report sign up … it’s free! of their tour will also be found in next week’s Herald. -

Mounted Troops in Zululand Brian M

Mounted Troops in Zululand Brian M. Best ____________________________________________________________________________________________ With Britain’s attention taken up with the events in Afghanistan during 1878, the War Office concentrated all available Imperial regiments on the North West Frontier. These naturally included units of cavalry sent to act as the eyes for the huge columns that began their advance during November. At the same time in South Africa, unbeknown to the British Government, Sir Bartle Frere, the High Commissioner, and Lord Chelmsford, the Army Commander, was preparing to invade Zululand. Chelmsford was relying on the Imperial regiments with which he had successfully defeated the Gaikas and Gcalekas during the recent Frontier War. These were infantry battalions only, for there were no cavalry stationed in South Africa. In order to fill this gap, volunteers were taken from the 3rd, 13th, 24th, 80th and 90th Regiments and formed into two squadrons of Mounted Infantry with a total strength of 300 men. Many of these men were generally experienced with horses from their former civilian occupations, having been grooms, ostlers etc. Others, however, were not and it took sometime to train these would-be cavalrymen. Once proficient, the Mounted Infantry acquitted themselves very well. The men were dressed as normal infantrymen, except that they wore cord breeches and calf-length leather gaiters. Instead of pouches, they carried their ammunition in bandoliers draped across the chest. Unlike other mounted troops, the mounted infantrymen were armed with a Martini-Henry rifle instead of the shorter carbine. For the officers, the transition was an easy one as they were all mounted as a matter of course. -

Throughout the 1950S the Liberal Party of South Africa Suffered Severe Internal Conflict Over Basic Issues of Policy and Strategy

Throughout the 1950s the Liberal Party of South Africa suffered severe internal conflict over basic issues of policy and strategy. On one level this stemmed from the internal dynamics of a small party unequally divided between the Cape, Transvaal and Natal, in terms of membership, racial composftion and political traditon. This paper and the larger work from which it is taken , however, argue inter alia that the conflict stemmed to a greater degree from a more fundamental problem, namely differing interpretations of liberalism and thus of the role of South African liberals held by various elements within the Liberal Party (LP). This paper analyses the political creed of those parliamentary and other liberals who became the early leaders of the LP. Their standpoint developed in specific circumstances during the period 1947-1950, and reflected opposition to increasingly radical black political opinion and activity, and retreat before the unfolding of apartheid after 1948. This particular brand of liberalism was marked by a rejection of extra- parliamentary activity, by a complete rejection of the univensal franchise, and by anti-communism - the negative cgaracteristics of the early LP, but also the areas of most conflict within the party. The liberals under study - including the Ballingers, Donald Molteno, Leo Marquard, and others - were all prominent figures. All became early leaders of the Liberal Party in 1953, but had to be *Ihijackedffigto the LP by having their names published in advance of the party being launched. The strategic prejudices of a small group of parliamentarians, developed in the 1940s, were thus to a large degree grafted on to non-racial opposition politics in the 1950s through an alliance with a younger generation of anti-Nationalists in the LP. -

The People's Hospital

THE PEOPLE’S HOSPITAL: A HISTORY OF McCORDS, DURBAN, 1890s–1970s Julie Parle and Vanessa Noble Occasional Publications of the Natal Society Foundation PIETERMARITZBURG 2017 The People’s Hospital: A History of McCords, Durban, 1890s–1970s © Julie Parle and Vanessa Noble 2017 Published in 2017 in Pietermaritzburg by the Trustees of the Natal Society Foundation under its imprint ‘Occasional Publications of the Natal Society Foundation’. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without reference to the publishers, the trustees of the Natal Society Foundation, Pietermaritzburg. Natal Society Foundation website: http://www.natalia.org.za/ ISBN 978-0-9921766-9-3 Editor: Christopher Merrett Proofreader: Cathy Rich Munro Cartographer: Marise Bauer Indexer: Christopher Merrett Design & layout: Jo Marwick Body text: Times New Roman 11pt Front and footnotes: Times New Roman 9pt Front cover: McCord Hospital: ward scene, c.1918 (PAR, A608, American Board of Missions Collection, photograph C.5529); ‘The people’s hospital’ (Post (Natal edition) 24 February 1963). Back cover: The McCord Hospital emblem (CC, MHP, Boxes 7 and 8 (2007) – McCords 7 and 8, ALP, Series II: McCord Hospital Documents: Golden Jubilee 1909–1959: A Report on McCord Zulu Hospital) Printed by CPW Printers, Pietermaritzburg CONTENTS Abbreviations and acronyms List of maps and figures Preface Acknowledgements Introduction Chapter 1 ‘Bringing light to the nation?’: missionaries and medicine in Natal and Zululand 1 -

From Mission School to Bantu Education: a History of Adams College

FROM MISSION SCHOOL TO BANTU EDUCATION: A HISTORY OF ADAMS COLLEGE BY SUSAN MICHELLE DU RAND Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the Department of History, University of Natal, Durban, 1990. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Page i ABSTRACT Page ii ABBREVIATIONS Page iii INTRODUCTION Page 1 PART I Page 12 "ARISE AND SHINE" The Founders of Adams College The Goals, Beliefs and Strategies of the Missionaries Official Educational Policy Adams College in the 19th Century PART II Pase 49 o^ EDUCATION FOR ASSIMILATION Teaching and Curriculum The Student Body PART III Page 118 TENSIONS. TRANSmON AND CLOSURE The Failure of Mission Education Restructuring African Education The Closure of Adams College CONCLUSION Page 165 APPENDICES Page 170 BIBLIOGRAPHY Page 187 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Paul Maylam for his guidance, advice and dedicated supervision. I would also like to thank Michael Spencer, my co-supervisor, who assisted me with the development of certain ideas and in supplying constructive encouragement. I am also grateful to Iain Edwards and Robert Morrell for their comments and critical reading of this thesis. Special thanks must be given to Chantelle Wyley for her hard work and assistance with my Bibliography. Appreciation is also due to the staff of the University of Natal Library, the Killie Campbell Africana Library, the Natal Archives Depot, the William Cullen Library at the University of the Witwatersrand, the Central Archives Depot in Pretoria, the Borthwick Institute at the University of York and the School of Oriental and African Studies Library at the University of London. -

An African American in South Africa: the Travel Notes of Ralph J Bunche, 28 September 1937-1 January 1938'

H-SAfrica Mkhize on Bunche, 'An African American in South Africa: The Travel Notes of Ralph J Bunche, 28 September 1937-1 January 1938' Review published on Saturday, September 1, 2001 Ralph J. Bunche. An African American in South Africa: The Travel Notes of Ralph J Bunche, 28 September 1937-1 January 1938. Edited by Robert R Edgar. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2001. xv + 398 pp. $24.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-8214-1394-4. Reviewed by Sibongiseni Mkhize (Durban Local History Museums, South Africa) Published on H- SAfrica (September, 2001) I have found that my Negro ancestry is something that can be exploited here I have found that my Negro ancestry is something that can be exploited here This book is an edited version of Ralph Bunche's notes which he wrote while on a three month tour of South Africa. The book was first published in hardback in 1992 and it has been re-issued in paperback in 2001. Ralph Bunche was born in Detroit in 1904 and grew up in Los Angeles. He began his tertiary studies at the University of California in Los Angeles in 1927, and later moved on to Harvard University in 1928. After graduating with an MA degree at Harvard, Bunche was offered a teaching post at Howard University where he established the Department of Political Science. In 1932 he went back to Harvard, where he began studying for his doctorate--his topic was French Administration in Togoland and Dahomey--which he obtained in 1934. His initial interest was to compare mixed-race experiences in Brazil and America. -

EASTERN CAPE NARL 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive)

EASTERN CAPE NARL 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Andrew (Andrew Whitfield) 2 Nosimo (Nosimo Balindlela) 3 Kevin (Kevin Mileham) 4 Terri Stander 5 Annette Steyn 6 Annette (Annette Lovemore) 7 Confidential Candidate 8 Yusuf (Yusuf Cassim) 9 Malcolm (Malcolm Figg) 10 Elza (Elizabeth van Lingen) 11 Gustav (Gustav Rautenbach) 12 Ntombenhle (Rulumeni Ntombenhle) 13 Petrus (Petrus Johannes de WET) 14 Bobby Cekisani 15 Advocate Tlali ( Phoka Tlali) EASTERN CAPE PLEG 2014 (Approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Athol (Roland Trollip) 2 Vesh (Veliswa Mvenya) 3 Bobby (Robert Stevenson) 4 Edmund (Peter Edmund Van Vuuren) 5 Vicky (Vicky Knoetze) 6 Ross (Ross Purdon) 7 Lionel (Lionel Lindoor) 8 Kobus (Jacobus Petrus Johhanes Botha) 9 Celeste (Celeste Barker) 10 Dorah (Dorah Nokonwaba Matikinca) 11 Karen (Karen Smith) 12 Dacre (Dacre Haddon) 13 John (John Cupido) 14 Goniwe (Thabisa Goniwe Mafanya) 15 Rene (Rene Oosthuizen) 16 Marshall (Marshall Von Buchenroder) 17 Renaldo (Renaldo Gouws) 18 Bev (Beverley-Anne Wood) 19 Danny (Daniel Benson) 20 Zuko (Prince-Phillip Zuko Mandile) 21 Penny (Penelope Phillipa Naidoo) FREE STATE NARL 2014 (as approved by the Federal Executive) Rank Name 1 Patricia (Semakaleng Patricia Kopane) 2 Annelie Lotriet 3 Werner (Werner Horn) 4 David (David Christie Ross) 5 Nomsa (Nomsa Innocencia Tarabella Marchesi) 6 George (George Michalakis) 7 Thobeka (Veronica Ndlebe-September) 8 Darryl (Darryl Worth) 9 Hardie (Benhardus Jacobus Viviers) 10 Sandra (Sandra Botha) 11 CJ (Christian Steyl) 12 Johan (Johannes -

To the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005)

Index to the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005) Adams, Ryan Author "Return to The Marvelous Land of Oz Producer In Search of Dorothy (review): One Hundred Years Later": "Answering Bell" (Music Video): 2005:49:1:32-33 2004:48:3:26-36 2002:46:1:3 Apocrypha Baum, Dr. Henry "Harry" Clay (brother Adventures in Oz (2006) (see Oz apocrypha): 2003:47:1:8-21 of LFB) Collection of Shanower's five graphic Apollo Victoria Theater Photograph: 2002:46:1:6 Oz novels.: 2005:49:2:5 Production of Wicked (September Baum, Lyman Frank Albanian Editions of Oz Books (see 2006): 2005:49:3:4 Astrological chart: 2002:46:2:15 Foreign Editions of Oz Books) "Are You a Good Ruler or a Bad Author Albright, Jane Ruler?": 2004:48:1:24-28 Aunt Jane's Nieces (IWOC Edition "Three Faces of Oz: Interviews" Arlen, Harold 2003) (review): 2003:47:3:27-30 (Robert Sabuda, "Prince of Pop- National Public Radio centennial Carodej Ze Zeme Oz (The ups"): 2002:46:1:18-24 program. Wonderful Wizard of Oz - Czech) Tribute to Fred M. Meyer: "Come Rain or Come Shine" (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 2004:48:3:16 Musical Celebration of Harold Carodejna Zeme Oz (The All Things Oz: 2002:46:2:4 Arlen: 2005:49:1:5 Marvelous Land of Oz - Czech) All Things Oz: The Wonder, Wit, and Arne Nixon Center for Study of (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 Wisdom of The Wizard of Oz Children's Literature (Fresno, CA): Charobnak Iz Oza (The Wizard of (review): 2004:48:1:29-30 2002:46:3:3 Oz - Serbian) (review): Allen, Zachary Ashanti 2005:49:2:33 Convention Report: Chesterton Actress The Complete Life and -

MEMORY of the WORLD REGISTER the Wizard of Oz

MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming 1939), produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer REF N° 2006-10 PART A – ESSENTIAL INFORMATION 1 SUMMARY In 1939, as the world fell into the chaos of war, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released a film that espoused kindness, charity, friendship, courage, fortitude, love and generosity. It was dedicated to the “young, and the young in heart” and today it remains one of the most beloved works of cinema, embraced by audiences of all ages throughout the world. It is one of the most widely seen and influential films in all of cinema history. The Wizard of Oz (1939) has become a true cinema classic, one that resonates with hope and love every time Dorothy Gale (the inimitable Judy Garland in her signature screen performance) wistfully sings “Over the Rainbow” as she yearns for a place where “troubles melt like lemon drops” and the sky is always blue. George Eastman House takes pride in nominating The Wizard of Oz for inclusion in the Memory of the World Register because as custodian of the original Technicolor 3-strip nitrate negatives and the black and white sequences preservation negatives and soundtrack, the Museum has conserved these precious artefacts, thus ensuring the survival of this film for future generations. Working in partnership with the current legal owner, Warner Bros., the Museum has made it possible for this beloved film classic to continue to enchant and delight audiences. The original YCM negatives have been conserved at the Museum since 1975, and Warner Bros. recently completed our holdings of the film by assigning the best surviving preservation elements of the opening and closing black and white sequences and the soundtrack to our care. -

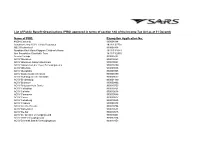

List of Section 18A Approved PBO's V1 0 7 Jan 04

List of Public Benefit Organisations (PBO) approved in terms of section 18A of the Income Tax Act as at 31 December 2003: Name of PBO: Exemption Application No: 46664 Concerts 930004984 Aandmymering ACVV Tehuis Bejaardes 18/11/13/2738 ABC Kleuterskool 930005938 Abraham Kriel Maria Kloppers Children's Home 18/11/13/1444 Abri Foundation Charitable Trust 18/11/13/2950 Access College 930000702 ACVV Aberdeen 930010293 ACVV Aberdeen Aalwyn Ouetehuis 930010021 ACVV Adcock/van der Vyver Behuisingskema 930010259 ACVV Albertina 930009888 ACVV Alexandra 930009955 ACVV Baakensvallei Sentrum 930006889 ACVV Bothasig Creche Dienstak 930009637 ACVV Bredasdorp 930004489 ACVV Britstown 930009496 ACVV Britstown Huis Daniel 930010753 ACVV Calitzdorp 930010761 ACVV Calvinia 930010018 ACVV Carnarvon 930010546 ACVV Ceres 930009817 ACVV Colesberg 930010535 ACVV Cradock 930009918 ACVV Creche Prieska 930010756 ACVV Danielskuil 930010531 ACVV De Aar 930010545 ACVV De Grendel Versorgingsoord 930010401 ACVV Delft Versorgingsoord 930007024 ACVV Dienstak Bambi Versorgingsoord 930010453 ACVV Disa Tehuis Tulbach 930010757 ACVV Dolly Vermaak 930010184 ACVV Dysseldorp 930009423 ACVV Elizabeth Roos Tehuis 930010596 ACVV Franshoek 930010755 ACVV George 930009501 ACVV Graaff Reinet 930009885 ACVV Graaff Reinet Huis van de Graaff 930009898 ACVV Grabouw 930009818 ACVV Haas Das Care Centre 930010559 ACVV Heidelberg 930009913 ACVV Hester Hablutsel Versorgingsoord Dienstak 930007027 ACVV Hoofbestuur Nauursediens vir Kinderbeskerming 930010166 ACVV Huis Spes Bona 930010772 ACVV