The People's Hospital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Mission School to Bantu Education: a History of Adams College

FROM MISSION SCHOOL TO BANTU EDUCATION: A HISTORY OF ADAMS COLLEGE BY SUSAN MICHELLE DU RAND Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the Department of History, University of Natal, Durban, 1990. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Page i ABSTRACT Page ii ABBREVIATIONS Page iii INTRODUCTION Page 1 PART I Page 12 "ARISE AND SHINE" The Founders of Adams College The Goals, Beliefs and Strategies of the Missionaries Official Educational Policy Adams College in the 19th Century PART II Pase 49 o^ EDUCATION FOR ASSIMILATION Teaching and Curriculum The Student Body PART III Page 118 TENSIONS. TRANSmON AND CLOSURE The Failure of Mission Education Restructuring African Education The Closure of Adams College CONCLUSION Page 165 APPENDICES Page 170 BIBLIOGRAPHY Page 187 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Paul Maylam for his guidance, advice and dedicated supervision. I would also like to thank Michael Spencer, my co-supervisor, who assisted me with the development of certain ideas and in supplying constructive encouragement. I am also grateful to Iain Edwards and Robert Morrell for their comments and critical reading of this thesis. Special thanks must be given to Chantelle Wyley for her hard work and assistance with my Bibliography. Appreciation is also due to the staff of the University of Natal Library, the Killie Campbell Africana Library, the Natal Archives Depot, the William Cullen Library at the University of the Witwatersrand, the Central Archives Depot in Pretoria, the Borthwick Institute at the University of York and the School of Oriental and African Studies Library at the University of London. -

An African American in South Africa: the Travel Notes of Ralph J Bunche, 28 September 1937-1 January 1938'

H-SAfrica Mkhize on Bunche, 'An African American in South Africa: The Travel Notes of Ralph J Bunche, 28 September 1937-1 January 1938' Review published on Saturday, September 1, 2001 Ralph J. Bunche. An African American in South Africa: The Travel Notes of Ralph J Bunche, 28 September 1937-1 January 1938. Edited by Robert R Edgar. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2001. xv + 398 pp. $24.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-8214-1394-4. Reviewed by Sibongiseni Mkhize (Durban Local History Museums, South Africa) Published on H- SAfrica (September, 2001) I have found that my Negro ancestry is something that can be exploited here I have found that my Negro ancestry is something that can be exploited here This book is an edited version of Ralph Bunche's notes which he wrote while on a three month tour of South Africa. The book was first published in hardback in 1992 and it has been re-issued in paperback in 2001. Ralph Bunche was born in Detroit in 1904 and grew up in Los Angeles. He began his tertiary studies at the University of California in Los Angeles in 1927, and later moved on to Harvard University in 1928. After graduating with an MA degree at Harvard, Bunche was offered a teaching post at Howard University where he established the Department of Political Science. In 1932 he went back to Harvard, where he began studying for his doctorate--his topic was French Administration in Togoland and Dahomey--which he obtained in 1934. His initial interest was to compare mixed-race experiences in Brazil and America. -

The Legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli's Christian-Centred Political

Faith and politics in the context of struggle: the legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli’s Christian-centred political leadership Simangaliso Kumalo Ministry, Education & Governance Programme, School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa Abstract Albert John Mvumbi Luthuli, a Zulu Inkosi and former President-General of the African National Congress (ANC) and a lay-preacher in the United Congregational Church of Southern Africa (UCCSA) is a significant figure as he represents the last generation of ANC presidents who were opposed to violence in their execution of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. He attributed his opposition to violence to his Christian faith and theology. As a result he is remembered as a peace-maker, a reputation that earned him the honour of being the first African to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Also central to Luthuli’s leadership of the ANC and his people at Groutville was democratic values of leadership where the voices of people mattered including those of the youth and women and his teaching on non-violence, much of which is shaped by his Christian faith and theology. This article seeks to examine Luthuli’s legacy as a leader who used peaceful means not only to resist apartheid but also to execute his duties both in the party and the community. The study is a contribution to the struggle of maintaining peace in the political sphere in South Africa which is marked by inter and intra party violence. The aim is to examine Luthuli’s legacy for lessons that can be used in a democratic South Africa. -

“The Struggle for Survival:”* Adams College's Battle with the Bantu

“The struggle for survival:”* Adams College’s battle with the Bantu Education Act Percy Ngonyama Honours Research Proposal, Department of Historical Studies University of KwaZulu-Natal Introduction “Adams was the home of inter-racial conferences and gatherings, and its school arrangements were made, not to exemplify apartheid, but to the glory of God. Therefore it became in the eyes of the government an ‘unnational school’, an alien institution, and therefore it had to go.”1 Subsequent to failed attempts to register as an independent school in the wake of the Bantu Education Act of 1953, on 02 December 1956, after more than a century of existence, Adams College, combining a high school, a music school, a teachers training college, and an industrial school, held its final assembly. When Adams reopened in January 1957, with most of the staff having left, including George Copeland Grant-principal of the College from 1949-1956,it had been renamed ‘Amanzimtoti Zulu College’, and was now under the authority of the Nationalist Party government’s department of Native Affairs’ Bantu Education subdivision. The process culminating in what must have been, for many, an extremely emotional occasion on December 02, had begun in 1949 with the constitution of the Eiselen Commission, headed by Dr W.W.M Eiselen- inspector of Native Education in the Transvaal Province- whose report, two years later, paved the way for the passing of the infamous Bantu Education Act, which was, inter alia, aimed at transferring education of the so-called “Bantu” from Missions, the main source of black education prior to the passing of the Bantu Education Act, to the department of Bantu Affairs. -

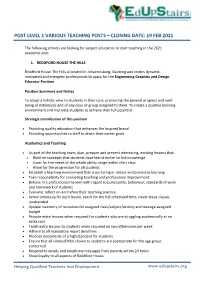

Post Level 1 Various Teaching Posts – Closing Date: 19 Feb 2021

POST LEVEL 1 VARIOUS TEACHING POSTS – CLOSING DATE: 19 FEB 2021 The following schools are looking for subject educators to start teaching in the 2021 academic year: 1. REDDFORD HOUSE THE HILLS Reddford House The Hills is located in Johannesburg, Gauteng and invites dynamic, motivated and energetic professionals to apply for the Engineering Graphics and Design Educator Position Position Summary and Duties To adopt a holistic view to students in their care, promoting the general progress and well- being of individuals and of any class or group assigned to them. To create a positive learning environment and motivate students to achieve their full potential. Strategic contribution of this position Providing quality education that enhances the Inspired brand Providing opportunities to staff to attain their career goals Academics and Teaching As part of the teaching team, plan, prepare and present interesting, exciting lessons that: Build on concepts that students have learnt earlier to link knowledge Cater for the needs of the whole ability range within their class Allow for the progression for all students Establish a teaching environment that is nurturing in nature and promotes learning Take responsibility for evaluating teaching and professional improvement Behave in a professional manner with regard to punctuality, behaviour, standards of work and homework of students Evaluate, reflect on and refine their teaching practice Arrive timeously for each lesson, teach for the full scheduled time; never leave classes unattended Update -

African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper 15 (Part 2); Ton Dietz South Africa: NATAL: Part 2: Postmarks a -D; Version January 2017

African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper 15 (Part 2); Ton Dietz South Africa: NATAL: Part 2: Postmarks A -D; Version January 2017 African Studies Centre Leiden African Postal Heritage APH Paper Nr 15, part 2 Ton Dietz NATAL: POSTMARKS A-D Version January 2017 Introduction Postage stamps and related objects are miniature communication tools, and they tell a story about cultural and political identities and about artistic forms of identity expressions. They are part of the world’s material heritage, and part of history. Ever more of this postal heritage becomes available online, published by stamp collectors’ organizations, auction houses, commercial stamp shops, online catalogues, and individual collectors. Virtually collecting postage stamps and postal history has recently become a possibility. These working papers about Africa are examples of what can be done. But they are work-in-progress! Everyone who would like to contribute, by sending corrections, additions, and new area studies can do so by sending an email message to the APH editor: Ton Dietz ([email protected]). You are welcome! Disclaimer: illustrations and some texts are copied from internet sources that are publicly available. All sources have been mentioned. If there are claims about the copy rights of these sources, please send an email to [email protected], and, if requested, those illustrations will be removed from the next version of the working paper concerned. 96 African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper 15 (Part 2); Ton Dietz South Africa: NATAL: Part 2: Postmarks A -D; Version January 2017 African Studies Centre Leiden P.O. -

R603 (Adams) Settlement Plan & Draft Scheme

R603 (ADAMS) SETTLEMENT PLAN & DRAFT SCHEME CONTRACT NO.: 1N-35140 DEVELOPMENT PLANNING ENVIRONMENT AND MANAGEMENT UNIT STRATEGIC SPATIAL PLANNING BRANCH 166 KE MASINGA ROAD DURBAN 4000 2019 FINAL REPORT R603 (ADAMS) SETTLEMENT PLAN AND DRAFT SCHEME TABLE OF CONTENTS 4.1.3. Age Profile ____________________________________________ 37 4.1.4. Education Level ________________________________________ 37 1. INTRODUCTION _______________________________________________ 7 4.1.5. Number of Households __________________________________ 37 4.1.6. Summary of Issues _____________________________________ 38 1.1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT ____________________________________ 7 4.2. INSTITUTIONAL AND LAND MANAGEMENT ANALYSIS ___________________ 38 1.2. PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ______________________________________ 7 4.2.1. Historical Background ___________________________________ 38 1.3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ________________________________________ 7 4.2.2. Land Ownership _______________________________________ 39 1.4. MILESTONES/DELIVERABLES ____________________________________ 8 4.2.3. Institutional Arrangement _______________________________ 40 1.5. PROFESSIONAL TEAM _________________________________________ 8 4.2.4. Traditional systems/practices _____________________________ 41 1.6. STUDY AREA _______________________________________________ 9 4.2.5. Summary of issues _____________________________________ 42 1.7. OUTLINE OF THE REPORT ______________________________________ 10 4.3. SPATIAL TRENDS ____________________________________________ 42 2. LEGISLATIVE -

Stella Aurorae: Establishing Kwazulu-Natal's First University

Stella Aurorae: Establishing KwaZulu-Natal’s First University The early quest for university it might develop into a ‘young men’s uni- education versity’. By the 1850s there were already KwaZulu-Natal’s first fully-fledged uni- more than 500 such Institutes in Britain, versity, the University of Natal, was originating in Glasgow for the purpose established sixty years ago, on 15 March of providing working men with part-time 1949. The Natal University College from adult education. Like so many of them, which it developed came into existence a their Durban counterpart became no more century ago, on 11 December 1909. Such than a literary, recreational and social club an institution had first been envisaged before its subsequent closure. It did, how- as early as the mid-nineteenth century, ever, provide the basis for the city’s first though from the beginning, given the co- public library.1 lonial time and place, the intention was to In 1858 the more established and afflu- advance white (and initially male) educa- ent Cape Colony took the first meaningful tion. The issue of contention was where step towards the creation of a university the university should be sited – in Durban in southern Africa when it set up a Board or Pietermaritzburg. In September 1853 a of Public Examiners. Its function was to group of prominent citizens launched the examine and issue certificates to candi- Durban Mechanics’ Institute and, within dates prepared by secondary schools in three years, there were expectations that the fields of Literature and Science, Law 65 Natalia 39 (2009), Bill Guest pp. -

Kwazulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal Municipality Ward Voting District Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830014 INDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.99047 29.45013 NEXT NDAWANA SENIOR SECONDARY ELUSUTHU VILLAGE, NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830025 MANGENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.06311 29.53322 MANGENI VILLAGE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830081 DELAMZI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09754 29.58091 DELAMUZI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830799 LUKHASINI PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.07072 29.60652 ELUKHASINI LUKHASINI A/A UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830878 TSAWULE JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.05437 29.47796 TSAWULE TSAWULE UMZIMKHULU RURAL KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830889 ST PATRIC JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.07164 29.56811 KHAYEKA KHAYEKA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11830890 MGANU JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -29.98561 29.47094 NGWAGWANE VILLAGE NGWAGWANE UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305001 11831497 NDAWANA PRIMARY SCHOOL -29.98091 29.435 NEXT TO WESSEL CHURCH MPOPHOMENI LOCATION ,NDAWANA A/A UMZIMKHULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830058 CORINTH JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.09861 29.72274 CORINTH LOC UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830069 ENGWAQA JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.13608 29.65713 ENGWAQA LOC ENGWAQA UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830867 NYANISWENI JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL -30.11541 29.67829 ENYANISWENI VILLAGE NYANISWENI UMZIMKULU KZN435 - Umzimkhulu 54305002 11830913 EDGERTON PRIMARY SCHOOL -30.10827 29.6547 EDGERTON EDGETON UMZIMKHULU -

ILITHA HIA DESKTOP.Pdf

Page 1 of 19 A DESKTOP STUDY FOR THE PLACEMENT AND OPERATION OF THE AERIAL FIBRE OPTIC NETWORK IN KWAMASHU, INANDA, PHOENIX, AND NTUZUMA, ETHEKWINI MUNICIPALITY FOR ILITHA TELECOMMUNICATIONS (PTY) LTD DATE: 14 FEBRUARY 2021 By Gavin Anderson Umlando: Archaeological Surveys and Heritage Management PO Box 10153, Meerensee, 3901 Phone: 035-7531785 Cell: 0836585362 [email protected] ILITHA HIA DESKTOP Umlando 22/03/2021 Page 2 of 19 Abbreviations HP Historical Period IIA Indeterminate Iron Age LIA Late Iron Age EIA Early Iron Age ISA Indeterminate Stone Age ESA Early Stone Age MSA Middle Stone Age LSA Late Stone Age HIA Heritage Impact Assessment PIA Palaeontological Impact Assessment ILITHA HIA DESKTOP Umlando 22/03/2021 Page 3 of 19 INTRODUCTION Ilitha Telecommunications (Pty) Ltd (Ilitha), is finalising financing from the Development Bank of South Africa (DBSA) for the placement and operation of the aerial fibre optic network in KwaMashu, Inanda, Phoenix, and Ntuzuma, in the eThekwini Municipality. Aerial deployment of a fibre optic network offers significant cost reductions compared to traditional trenching methods. Design of the Ilitha aerial fibre network will closely resemble the existing electricity distribution network in most residential areas. This will enable pricing to be more affordable compared to traditional data providers. The footprint of the Ilitha fibre roll out will stretch across a 96.2 km2 area which covers communities in KwaMashu, Inanda, Phoenix, and Ntuzuma... The project area is situated approximately 12 kilometres north of Durban and is bordered by Reservoir Hills & Newlands East to the south, KwaDabeka & Molweni to the west, Mount Edgecombe & Blackburn Estate to the east and Mawothi & Trenance Park to the north. -

At Adams College

Welcome Address by Mayor of eThekwini, Cllr Zandile Gumede at the Opening of New Classes at Adams College Programme Director, His Excellency- President Jacob Zuma, Premier of KwaZulu-Natal – Hon Willies Mchunu, The Former Chairperson of the African Union, Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, Ministers Present, MEC Present, Amakhosi nezinduna, Adams College Development Trust Chairperson, Prof Sihawukele Ngubane, The Principal of Adams College, Mr Thulani Khumalo and all staff and learners Sanibona Adams College stands out as one of the most important institutions that shaped the development of black people in the country and the region. This is the only school in this country that has produced two African Heads of State and Government and key leaders, the former President of Botswana, Sir Seretse Khama and a former President Milton Obote of Uganda and also Mr Joshua Nkomo of Zimbabwe. It has produced four African National Congress Presidents: Dr. JL Dube, Dr. Pixley ka Isaka Seme, Mr. JT Gumede and Chief Albert Luthuli. It produced the First ANC Youth League President, Mr. Anton Lembede. Adams college also prides itself on having produced Prof ZK Matthews, the father of the Freedom Charter, the First African medical doctor, Dr. John Nembula; musical genius, Prof Khabi Mngoma, the late former Chief Justice Pius Langa and also its ambassador, the AU Commission Chairperson Dr Dlamini-Zuma. Adams college also produced the presidents of two political parties in the country, Inkosi Mangosuthu Buthelezi of the IFP and the late Zephania Mothopheng of the PAC. It also prides itself on having two Attorneys-Generals of African States as former students, Herbert Chitepo of Zimbabwe and Charles Njonjo of Kenya. -

Kwazulu-Natal School Co-Ordinates - Alphabetical

KwaZulu-Natal School Co-ordinates - Alphabetical Longitude - EAST Latitude - SOUTH School Schooltype Health District Degrees Minutes Seconds Degrees Minutes Seconds AANGELEGEN P Primary Amajuba 30 18 38.16 27 29 12.228 ABAMBO P Primary eThekwini Municipality 30 47 17.88 29 44 19.5 ABANTUNGWA H Secondary Uthukela 29 42 38.592 29 5 46.5 ABAQULUSI H Secondary Zululand 31 2 18.24 27 28 22.512 ABATHWA JP Primary Zululand 30 54 6.192 28 16 42.6 ACACIA P Primary eThekwini Municipality 31 0 51.552 29 39 21.348 ACACIAVALE P Primary Uthukela 29 48 8.928 28 35 39.84 ACTON HOMES PUBLIC Primary Uthukela 29 24 27.108 28 38 43.26 ADAMS COLLEGE Secondary eThekwini Municipality 30 49 2.892 30 1 48.252 ADAMS SP Primary eThekwini Municipality 30 49 20.892 30 1 39.108 ADDINGTON P Primary eThekwini Municipality 31 1 8.04 29 49 47.856 AI KAJEE P Primary uMgungundlovu 29 59 56.148 29 12 30.492 AJ MWELASE S Secondary eThekwini Municipality 30 56 8.88 29 56 3.12 ALBERT FALLS P Primary uMgungundlovu 30 25 44.76 29 25 6.708 ALBERT S Secondary Sisonke 29 27 47.34 30 24 33.372 ALBINI H Secondary eThekwini Municipality 30 41 13.56 29 50 9.78 ALDINVILLE SP Primary Ilembe 31 15 9.648 29 23 19.788 ALDORA P Primary uMgungundlovu 30 13 37.488 29 22 52.572 ALENCON P Primary eThekwini Municipality 30 53 56.652 29 59 15.972 ALEXANDRA H Secondary uMgungundlovu 30 23 16.26 29 36 58.68 ALIPORE P Primary eThekwini Municipality 30 57 49.968 29 56 44.448 ALLANDALE P (Pietermaritzburg) Primary uMgungundlovu 30 24 38.88 29 33 58.248 ALLERTON P Primary uMgungundlovu 30 9 23.4 29 26