The Struggle to Belong Dealing with Diversity in 21 Century Urban Settings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

FULLNAME CATEGORYTALUKA NAMRATA LAXIMI NARSHIV KAVLEKAR CFF Bardez

FULLNAME CATEGORYTALUKA NAMRATA LAXIMI NARSHIV KAVLEKAR CFF Bardez PRACHI SHIVDAS GAWANDALKER CFF Bardez SANJANA SOMNATH KANDOLKAR CFF Bardez DIKSHITA RAMJI NAIK CFF Bardez MANOJ KALLAPA TORALKAR CFF Bardez SHRIKRISHNA CHANDRAKANT HINDE CFF Bicholim VIDHYA DIPAK SHIRODKAR CFF Bicholim SHIVAJI BHIKAJI SATARDEKAR CFF Bicholim SANTOSH GOVIND NAIK CFF Canacona SURYAKANT HARISCHANDRA PAI CFF Canacona SAMPADA DHARMANAND SHET VEREKAR CFF Pernem RESHMA PURUSHOTTAM SHET NARVEKAR CFF Ponda RUPALI MAHESHWAR PAI CFF Ponda BIREN AUDUMBAR SHINKRE CFF Ponda LITA YESHWANT VERENKAR CFF Ponda SATISH VASSANT BUDHOLKAR CFF Salcete BHAKTI UMANATH VARKEKAR CFF Salcete SALMAN SHAIKH CFF Salcete BYRON CHARLES KEVIN RODRIGUES CFF Salcete NARAYAN SHUBASCHANDRA KARMALI CFF Salcete PRASAD RAMA NAIK DESAI CFF Salcete GAJANAN ARJUN GODLEKAR CFF Sanguem SHAMA RAMESH JOSHI CFF Sattari DASHARATH SURYA NAIK CFF Tiswadi JASMIN KISHOR PARSEKAR CFF Tiswadi SUNITA SUNIL KHATEKAR Ex SM Dharbandora RAMESH LAKAPPA IVANAGI Ex SM Mormugao SURESH KUMAR PAL Ex SM Mormugao OM PRAKASH Ex SM Mormugao SIDDHIKA MANGALDAS SHIRODKAR Ex SM Ponda SANIKA SANTOSH ADEL Ex SM Salcete SHILPA RAJU HEGDE Ex SM Salcete SUPRIYA KRISHNA HALANKAR General Bardez ARJUN ANKUSH GAWAS General Bardez JOSHUA LOBO General Bardez RUPESH BASURAJ HARIJAN General Bardez BLOSSOM MARTIN General Bardez SANTOSHI GURUDAS DHARGALKAR General Bardez MAYURSHI PANDURANG SALKAR General Bardez KIRTI SHIVAJI SHINDE General Bardez EMENDRA MONIZ General Bardez SIDDESH VITHAL SALGAONKAR General Bardez TANVI CHANDRAKANT NAIK General -

Periodical Report Periodical Report

ICTICT IncideIncidentsnts DatabaseDatabase PeriodicalPeriodical ReportReport January 2012 2011 The following is a summary and analysis of terrorist attacks and counter-terrorism operations that occurred during the month of January 2012, researched and recorded by the ICT database team. Among others: Irfan Ul Haq, 37 was sentenced to 50 months in prison on 5 January, for providing false documentation and attempting to smuggle a suspected Taliban member into the USA. On 5 January, Eyad Rashid Abu Arja, 47, a male Palestinian with dual Australian-Jordanian nationality, was sentenced to 30 months in prison in Israel for aiding Hamas. On 6 January, a bomb exploded in Damascus, Syria killing 26 people and wounding 63 others. ETA militant Andoni Zengotitabengoa, was sentenced on 6 January to 12 years in prison for the illegal possession of weapons, as well car theft, falsification of documents, assault and resisting arrest. On 9 January, Sami Osmakac, 25, was charged with plotting to attack crowded locations in Florida, USA. On 10 January, a car bomb exploded at a bus stand outside a shopping bazaar in Jamrud, northwestern Pakistan killing 26 people and injuring 72. Jermaine Grant, 29, a British man and three Kenyans were charged on 13 January in Mombasa, Kenya with possession of bomb-making materials and plotting to explode a bomb. On 13 January Thai police arrested Hussein Atris, 47, a Lebanese-Swedish man, who was suspected of having links to Hizballah. He was charged three days later with the illegal possession of explosive materials. On 14 January, a suicide bomber, disguised in a military uniform, killed 61 people and injured 139, at a checkpoint outside Basra, Iraq. -

Office of the Commissioner of Police, Mumbai - 1

Office of the Commissioner of Police, Mumbai - 1 - I N D E X Section 4(1)(b) I to XVII Topic B) Information given on topics Page No. Nos. The particulars of the Police Commissionerate organization, functions I 2 – 3 & duties II The Powers and duties of officers and employees 4 – 8 The procedure followed in decision-making process including channels of III 9 supervision and accountability. IV The norms set for the discharge of functions 10 The rules, regulations, instructions manuals and records held or used by V 11-13 employees for discharging their functions. VI A statement of categories and documents that are held or under control 14 The Particulars of any arrangement that exists for consultation with or VII representation by the members of the public in relation to the formulation 15 of policy or implementation thereof; A statement of the boards, councils, committees and bodies consisting of two or more persons constituted as its part for the purpose of its advice, VIII and as to whether meetings of those board, councils, committees and other 16 bodies are open to the public, or the minutes of such meetings are accessible for public; IX Directory of Mumbai Police Officials -2005. 17-23 The monthly remuneration received by each of the officers and X employees including the system of compensation as provided in the 24 regulations. The budget allocated to each agency, indicating the particulars of all plans 25-31 XI proposed, expenditures and reports of disbursements made; The manner of execution of subsidy programmes, including the amounts -

Bollywood Lens Syllabus

Bollywood's Lens on Indian Society Professor Anita Weiss INTL 448/548, Spring 2018 [email protected] Mondays, 4-7:20 pm 307 PLC; 541 346-3245 Course Syllabus Film has the ability to project powerful images of a society in ways conventional academic mediums cannot. This is particularly true in learning about India, which is home to the largest film industries in the world. This course explores images of Indian society that emerge through the medium of film. Our attention will be focused on the ways in which Indian society and history is depicted in film, critical social issues being explored through film; the depicted reality vs. the historical reality; and the powerful role of the Indian film industry in affecting social orientations and values. Course Objectives: 1. To gain an awareness of the historical background of the subcontinent and of contemporary Indian society; 2. To understand the sociocultural similarities yet significant diversity within this culture area; 3. To learn about the political and economic realities and challenges facing contemporary India and the rapid social changes the country is experiencing; 4. To learn about the Indian film industry, the largest in the world, and specifically Bollywood. Class format Professor Weiss will open each class with a short lecture on the issues which are raised in the film to be screened for that day. We will then view the selected film, followed by a short break, and then extensive in- class discussion. Given the length of most Bollywood films, we will need to fast-forward through much of the song/dance and/or fighting sequences. -

Drugs Main Source of Financing Terror in Region: US

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:X Issue No:36 Price: Afs.15 Weekend Issue, Sponsored by Etisalat FRIDAY . AUGUST 28. 2015 -Sunbula 06, 1394 H.S www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimes www.twitter.com/ afghanistantime Kabul renames Mojadedi condemns neighbors interferes Salma Dam as Kabul- Ashgabad signed five MoUs on his support to the government Afghan-India economy, energy, science and sports Former Mujahideen leaders formed Jihadi and National Par- and added that JNPHC as one friendship ities High Council (JNPHC) to support the government and of independent council, which Turkmen President says his government wants to launch some mega national security forces will support the government. dam He said they will never let projects in the fields of energy and railway construction Abdul Zuhoor Daesh and Taliban to turn Af- KABUL: The government of ghanistan into the nest of ter- By Akhtar M.Nikzad KABUL: Former Afghan Presi- need of the hour for tackling ter- Afghanistan has renamed the dent Sebghatulla Mojadedi on rorism, Mojadedi added. ror once again. Khalili called name of Salama dam to Afghan- Thursday lashed at a neighboring The JNPHC is comprised of on the Taliban they if they call KABUL: In response to the invi- however he vowed that Ashgabad commitment of Turkmenistan to themselves to be true Afghans India friendship dam follow- tation by the Afghan government, was ready to facilitate peace talks increase the power supply to Af- country for interfering in Afghans eight jihadi parties however its ing a robust investment by In- internal affairs. -

India 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Mumbai

India 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Mumbai This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Consulate General in Mumbai. OSAC encourages travelers to use this report to gain baseline knowledge of security conditions in India. For more in-depth information, review OSAC’s India-specific webpage for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses most of India at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution due to crime and terrorism. Some areas have increased risk: do not travel to the state of Jammu and Kashmir (except the eastern Ladakh region and its capital, Leh) due to terrorism and civil unrest; and do not travel to within ten kilometers of the border with Pakistan due to the potential for armed conflict. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System Overall Crime and Safety Situation The Consulate represents the United States in Western India, including the states of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Goa. Crime Threats The U.S. Department of State has assessed Mumbai as being a MEDIUM-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government. Although it is a city with an estimated population of more than 25 million people, Mumbai remains relatively safe for expatriates. Being involved in a traffic accident remains more probable than being a victim of a crime, provided you practice good personal security. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Lions Film Awards 01/01/1993 at Gd Birla Sabhagarh

1ST YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 01/01/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR TAPAS PAUL for RUPBAN BEST ACTRESS DEBASREE ROY for PREM BEST RISING ACTOR ABHISEKH CHATTERJEE for PURUSOTAM BEST RISING ACTRESS CHUMKI CHOUDHARY for ABHAGINI BEST FILM INDRAJIT BEST DIRECTOR BABLU SAMADDAR for ABHAGINI BEST UPCOMING DIRECTOR PRASENJIT for PURUSOTAM BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR MRINAL BANERJEE for CHETNA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER USHA UTHUP BEST PLAYBACK SINGER AMIT KUMAR BEST FILM NEWSPAPER CINE ADVANCE BEST P.R.O. NITA SARKAR for BAHADUR BEST PUBLICATION SUCHITRA FILM DIRECTORY SPECIAL AWARD FOR BEST FILM PREM TELEVISION BEST SERIAL NAGAR PARAY RUP NAGAR BEST DIRECTOR RAJA SEN for SUBARNALATA BEST ACTOR BHASKAR BANERJEE for STEPPING OUT BEST ACTRESS RUPA GANGULI for MUKTA BANDHA BEST NEWS READER RITA KAYRAL STAGE BEST ACTOR SOUMITRA CHATTERHEE for GHATAK BIDAI BEST ACTRESS APARNA SEN for BHALO KHARAB MAYE BEST DIRECTOR USHA GANGULI for COURT MARSHALL BEST DRAMA BECHARE JIJA JI BEST DANCER MAMATA SHANKER 2ND YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 24/12/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR CHIRANJEET for GHAR SANSAR BEST ACTRESS INDRANI HALDER for TAPASHYA BEST RISING ACTOR SANKAR CHAKRABORTY for ANUBHAV BEST RISING ACTRESS SOMA SREE for SONAM RAJA BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS RITUPARNA SENGUPTA for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST FILM AGANTUK OF SATYAJIT ROY BEST DIRECTOR PRABHAT ROY for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR BABUL BOSE for MON MANE NA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER INDRANI SEN for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER SAIKAT MITRA for MISTI MADHUR BEST CINEMA NEWSPAPER SCREEN BEST FILM CRITIC CHANDI MUKHERJEE for AAJKAAL BEST P.R.O. -

Recruiter's Handbook 2020

Recruiter’s Handbook 2020 VISION To create a state-of-the-art institution that sets new standards of world-class education in film, communication and creative arts. MISSION Benchmarking quality, inspiring innovation, encouraging creativity & moulding minds, by leading from the front in the field of film, media and entertainment education. ONE OF THE TEN BEST FILM SCHOOLS IN THE WORLD - THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER Degree & Diploma 5.5 ACRE programmes CAMPUS acceredited by the TISS 1300+ 2200+ STUDENTS Media & Film industry Alumni campus SCHOOL OF EVENT MANAGEMENT Subhash Ghai Founder & Chairman, Whistling Woods International Chairman, Mukta Arts Limited Member, Executive Committee, Film & Television Producers Guild of India Member, United Producers Forum Education Evangelist Karamveer Chakra Awardee Chairman, MESC Subhash Ghai is a globally renowned filmmaker having directed 19 films over a four-decade career, with 14 of them being blockbusters. Recipient of many national and international awards, he has also been honoured by the United States Senate. He has been a former Chairman of the Entertainment Committee of Trade body CII and also a member of FICCI, NASSCOM and TIE Global & its alliances. He has been invited to address various forums and seminars on corporate governance and the growth of Media & Entertainment industry globally and in India. He is presently serving as the Chairman of Media and Entertainment Skills Council (MESC). Message from the Founder & Chairman My journey as a filmmaker in the Media & Entertainment (M&E) industry has been a long and cherished one. Over the years, the one factor that has grounded me and contributed to my success is the basic film education I received from the film institute I studied in, coupled with my strong desire to learn and re-learn from my days as part of the Indian film industry. -

C1-27072018-Section

TATA CHEMICALS LIMITED LIST OF OUTSTANDING WARRANTS AS ON 27-08-2018. Sr. No. First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio / BENACC Amount 1 A RADHA LAXMI 106/1, THOMSAN RAOD, RAILWAY QTRS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI DELHI 110002 00C11204470000012140 242.00 2 A T SRIDHAR 248 VIKAS KUNJ VIKASPURI NEW DELHI 110018 0000000000C1A0123021 2,200.00 3 A N PAREEKH 28 GREATER KAILASH ENCLAVE-I NEW DELHI 110048 0000000000C1A0123702 1,628.00 4 A K THAPAR C/O THAPAR ISPAT LTD B-47 PHASE VII FOCAL POINT LUDHIANA NR CONTAINER FRT STN 141010 0000000000C1A0035110 1,760.00 5 A S OSAHAN 545 BASANT AVENUE AMRITSAR 143001 0000000000C1A0035260 1,210.00 6 A K AGARWAL P T C P LTD AISHBAGH LUCKNOW 226004 0000000000C1A0035071 1,760.00 7 A R BHANDARI 49 VIDYUT ABHIYANTA COLONY MALVIYA NAGAR JAIPUR RAJASTHAN 302017 0000IN30001110438445 2,750.00 8 A Y SAWANT 20 SHIVNAGAR SOCIETY GHATLODIA AHMEDABAD 380061 0000000000C1A0054845 22.00 9 A ROSALIND MARITA 505, BHASKARA T.I.F.R.HSG.COMPLEX HOMI BHABHA ROAD BOMBAY 400005 0000000000C1A0035242 1,760.00 10 A G DESHPANDE 9/146, SHREE PARLESHWAR SOC., SHANHAJI RAJE MARG., VILE PARLE EAST, MUMBAI 400020 0000000000C1A0115029 550.00 11 A P PARAMESHWARAN 91/0086 21/276, TATA BLDG. SION EAST MUMBAI 400022 0000000000C1A0025898 15,136.00 12 A D KODLIKAR BLDG NO 58 R NO 1861 NEHRU NAGAR KURLA EAST MUMBAI 400024 0000000000C1A0112842 2,200.00 13 A RSEGU ALAUDEEN C 204 ASHISH TIRUPATI APTS B DESAI ROAD BOMBAY 400026 0000000000C1A0054466 3,520.00 14 A K DINESH 204 ST THOMAS SQUARE DIWANMAN NAVYUG NAGAR VASAI WEST MAHARASHTRA THANA -

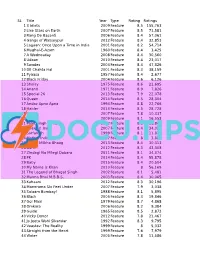

Aspirational Movie List

SL Title Year Type Rating Ratings 1 3 Idiots 2009 Feature 8.5 155,763 2 Like Stars on Earth 2007 Feature 8.5 71,581 3 Rang De Basanti 2006 Feature 8.4 57,061 4 Gangs of Wasseypur 2012 Feature 8.4 32,853 5 Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India 2001 Feature 8.2 54,714 6 Mughal-E-Azam 1960 Feature 8.4 3,425 7 A Wednesday 2008 Feature 8.4 30,560 8 Udaan 2010 Feature 8.4 23,017 9 Swades 2004 Feature 8.4 47,326 10 Dil Chahta Hai 2001 Feature 8.3 38,159 11 Pyaasa 1957 Feature 8.4 2,677 12 Black Friday 2004 Feature 8.6 6,126 13 Sholay 1975 Feature 8.6 21,695 14 Anand 1971 Feature 8.9 7,826 15 Special 26 2013 Feature 7.9 22,078 16 Queen 2014 Feature 8.5 28,304 17 Andaz Apna Apna 1994 Feature 8.8 22,766 18 Haider 2014 Feature 8.5 28,728 19 Guru 2007 Feature 7.8 10,337 20 Dev D 2009 Feature 8.1 16,553 21 Paan Singh Tomar 2012 Feature 8.3 16,849 22 Chakde! India 2007 Feature 8.4 34,024 23 Sarfarosh 1999 Feature 8.1 11,870 24 Mother India 1957 Feature 8 3,882 25 Bhaag Milkha Bhaag 2013 Feature 8.4 30,313 26 Barfi! 2012 Feature 8.3 43,308 27 Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara 2011 Feature 8.1 34,374 28 PK 2014 Feature 8.4 55,878 29 Baby 2015 Feature 8.4 20,504 30 My Name Is Khan 2010 Feature 8 56,169 31 The Legend of Bhagat Singh 2002 Feature 8.1 5,481 32 Munna Bhai M.B.B.S.