Corruption in Russia; Reiman's Telecommunication Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

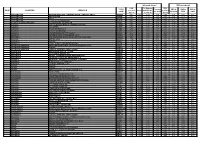

ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR TADIG CODE Calls

Calls made abroad SMS sent abroad Calls To Belgium SMS TADIG To zones SMS to SMS to SMS to ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR received Local and Europe received CODE 2,3 and 4 Belgium EUR ROW abroad (= zone1) abroad 3 AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS COMMUNICATION COMPANY 'AWCC' AFGAW 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN AREEBA MTN AFGAR 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN TDCA AFGTD 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT AFGHANISTAN AFGEA 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 1 ALANDS ISLANDS (FINLAND) ALANDS MOBILTELEFON AB FINAM 0,08 0,29 0,29 2,07 0,00 0,09 0,09 0,54 2 ALBANIA AMC (ALBANIAN MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS) ALBAM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA VODAFONE ALBVF 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA EAGLE MOBILE SH.A ALBEM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA DJEZZY (ORASCOM) DZAOT 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA ATM (MOBILIS) (EX-PTT Algeria) DZAA1 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA WATANIYA TELECOM ALGERIE S.P.A. -

Annual Report 2012 Annual Report

Annual Report 2012 Annual Report Annual Report www.AR2012.megafon.ru/en Chief Executive Officer I.V. Tavrin (signature) Chief Accountant L.N. Strelkina (signature) Annual Report 2012 CONTENTS MEGAFON MegaFon’s business model and key 2012 results 4 Finanсial and operational highlights for 2012 2012 marked a new 8 Our business page in MegaFon’s history STRATEGY Management’s overview of the results p. 14 and vision for growth 14 Letter of the Chairman of the Board LETTER 18 Letter of the CEO OF THE CHAIRMAN 22 Strategy OF THE BOARD 24 The Russian market in 2012 РERFORMANCE MegaFon’s operating and financial results 30 Review of operations 48 Finanсial review GOVERNANCE Free cash flow reached RUB 70.8 billion Corporate governance and risk management systems 52 Risk management p. 48 56 Corporate governance 69 Shareholder’s equity FINANCIAL REVIEW SUSTAINABILITY Our mission is Responsibility to employees to bring Russia and community together through 74 Sustainable development communication technology APPENDICES 82 Management responsibility statement 82 US GAAP Consolidated Financial Statements p. 74 128 Appendices SUSTAINABLE 160 Contacts DEVELOPMENT generated at BeQRious.com This Annual Report focuses principally on our operations in the Russian Federation. While we have operating subsidiaries in the For more information Republics of Tajikistan (TT mobile), Abkhazia (AQUafon-GSM) about MegaFon, see and South Ossetia (OSTELEKOM), they generate only 1% of the company website. our total consolidated revenues. Unless otherwise specifically The report is also indicated, this Annual Report provides consolidated financial and available online operational data www.AR2012.megafon.ru/en Approved Annual General Shareholders Meeting OJSC “MegaFon” Minutes dated 28.06.2013 Preliminarily Approved Board of Directors OJSC “MegaFon” Minutes № 192 (256) dated 14.05.2013 NATIONWIDE 4G AGREEMENT WITH NEW CAPEX LICENCE YOTA ON 4G NETWORK FRAMEWORK P. -

2G 3G 4G 5G > 181,400

Annual report 2019 Operational Results Infrastructure Network expansion MegaFon is the unrivalled leader in Russia 1 by number of base stations, with We are committed to maximising the speed and reliability of communications services for our subscribers, and are continuously investing in infrastructure and innovative technology. > 181,400 stations 2G 3G 4G 5G 1990s 2000s 2010s 2016–2019 Voice and SMS Mobile data and high- Mobile broadband and full- Ultrafast mobile internet, quality voice services scale IP network full-scale support of IoT ecosystems, and ultra-reliability MegaFon was the first in Russia to • provide 2G services in all • roll out a full-scale • launch the first 4G • demonstrate a record Russian regions commercial 3G network network (2012); connection speed • launch a commercial of 2.46 Gbit/s VoLTE network (2016); on a smartphone • demonstrate a data on a 5G network (2019); rate in excess of 1 Gbit/s • launch a 5G on a commercial lab – in collaboration smartphone (2018) with Saint Petersburg State University’s Graduate School of Management (2019) 1 According to Roscomnadzor as of 19 March 2020. 48 About MegaFon 14–35 Strategic report 36–81 Sustainability 82–109 Corporate governance, securities, and risk management 110–147 Financial statements and appendix 148–226 MegaFon’s base stations, ‘000 4G/LTE coverage, % 2019 70.0 50.7 60.7 181.4 2019 82 2018 70.5 49.4 49.6 169.5 2018 79 2017 69.1 48.0 40.6 157.7 2017 74 2G 3G 4G/LTE MegaFon’s strong portfolio of unique high-speed data 4G/LTE networks spectrum assets is an important competitive advantage. -

Telenor 15 Years in Russia

Telenor 15 years in Russia Telenor ASA, the Norwegian Telecommunications group, is happy to announce the start of celebrations of its 15th anniversary on the Russian market. Telenor first invested into the Russian market by establishing modern and digital fixed line connections to Murmansk and the Kola Peninsula in Russia's north. In St. Petersburg, Telenor was an owner from 1994 of North-West GSM, a company that later became MegaFon. Two other acquisitions, in Stavropol and Kaliningrad, were later consolidated into VimpelCom, following Telenor's first investment in that company in 1998. In 2003, Telenor merged the earlier acquired Comincom into the integrated services provider Golden Telecom. Today, Telenor holds 29.9% of the voting shares in VimpelCom and 18.4% of the shares in Golden Telecom. During its 15 years in Russia, Telenor has seen its asset value rise to over $10 billion, thus becoming the largest investor into the Russian telecoms. The Norwegian Minister of Trade and Industry Dag Terje Andersen, who is currently in Moscow to celebrate Telenor Russia's anniversary, said: "Telenor has been a long-term investor in Russia - both during periods of prosperity and periods of periods recession. Telenor has contributed with capital, knowledge, technology and value creation in the Russian telecom sector." He added: "I want to wish Telenor success in Russia in the future and congratulate it with its 15th anniversary in Russia." Telenor's CEO and President Jon Fredrik Baksaas, also in Moscow for the anniversary, added: "This is a great day for our business in Russia. And this is part of a long-term industrial relationship. -

Peterstar?” the Story Seemed Curious Since Just the Day Before It Was Announced in the Media That Mr

1 SUCCEEDING IN THE RUSSIAN TELECOMMUNICATION ENVIRONMENT The Feb 27, 2001 (p. 11) edition of the St. Petersburg Times included a startling story titled “End of the Road for PeterStar?” The story seemed curious since just the day before it was announced in the media that Mr. Sergei Kuznetsov, general director of PeterStar had been made the acting general director of Rostelecom pending almost certain share approval from the shareholders at their meeting scheduled for March 11, 2001. ZAO PeterStar was founded in October 1992 at the dawn of the emergence of the free markets and Perestroika in Russia. PeterStar was formed with the participation of Leningrad City Telephone Network2. Before 1992 all communication services in Russia were controlled directly by the Ministry of Communications without making any distinction between postal services, TV and radio broadcasting and telecommunications. In 1992, the government split up these three sectors while the whole telecommunications sector was restructured, 79 regional telephone companies which provide local services, six local trunk network operators which provide toll switching and one long-distance and international services provider Rostelecom were created. In 1992-93, more than 4000 licenses were granted to private operators. These operators have primarily focused on value added services such as digital overlay networks (Sovintel, Comstar, Combellga, PeterStar), cellular services (Moscow Cellular Communications, Mobile TeleSystems, Vympelcom, Delta Telecom, Northwest GSM etc.) and paging services. These licenses were meant to be the pillars on which the new Russian telecommunication industry was to be built. All these players have been helped by the fact that the existing networks did not posses the necessary technical, human and financial resources to satisfy the growing demand for value added services. -

Teliasonera Acquisition of MCT Corp. Coscom in Uzbekistan Indigo and Somoncom in Tajikistan Roshan in Afghanistan Strategic Acquisition Rationale

TeliaSonera Acquisition of MCT Corp. Coscom in Uzbekistan Indigo and Somoncom in Tajikistan Roshan in Afghanistan Strategic Acquisition Rationale • TeliaSonera will be the leading operator in Central Asian markets – Now: Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan – Existing via Fintur: Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan , Georgia and Moldova – Existing direct & unconsolidated: Turkey (incl. Ukraine indirectly) and Russia (incl. Tajikistan indirectly) • Attractive Growth Opportunity in terms of Addressable TeliaSonera MCT Market (Scandinavia, Baltics) – 10%-20% mobile penetration Fintur Turkcell – Less than 10% Fixed Line Penetration à wireless is attractive Megafon Yoigo • Natural Addition to TeliaSonera’s Eurasian Footprint – Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan complement current map in Central Asia – Significant economic/cultural ties between Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan • Company and Shareholders Honoring International Business Practices – Company’s operations developed by international practices: audited, subject to US rules Acquisition Cost TeliaSonera Acquisition of 100% of MCT Corp for a 100% enterprise value of approximately SEK 2.0 Sonera billion (USD 300 million) holding interest in Holding BV four Eurasian mobile operators: 100% • 99.97% interest in Uzbek-American Joint Venture “Coscom” LLC (Coscom) in MCT Corp. Uzbekistan Delaware Corporation • 60% interest in CJSC “Indigo- Tajikistan” (Indigo-Tajikistan) in Tajikistan and Venture Holdings Local Ventures • 59.4% in CJSC Joint Venture Management and MCT Dev. Corp. “Somoncom” -

Country Code City Code Country Name Rate Per Min 93 Afghanistan 1.575 93 7 Afghanistan-Mobile 1.2411 93 75 Afghanistan-Mobile AT

FirstLight Fiber International Calling Rates - effective April 1, 2017 *Rates are applicable to customers with standard rating voice products & services. Country Code City Code Country Name Rate per min 93 Afghanistan 1.575 93 7 Afghanistan-Mobile 1.2411 93 75 Afghanistan-Mobile AT 0.875 93 70 Afghanistan-Mobile AWCC 1.1634 93 78 Afghanistan-Mobile Etalis 1.12 93 77 Afghanistan-Mobile MTN 0.6496 93 79 Afghanistan-Mobile Roshan 1.1816 355 Albania 0.56 355 68 Albania-Mobile AMC 1.68 355 67 Albania-Mobile Eagle 1.7304 355 66 Albania-Mobile Plus 1.9243 355 69 Albania-Mobile Vodafone 1.47 355 4249 Albania-NGN 1.085 355 4250 Albania-NGN 1.085 355 4251 Albania-NGN 1.085 355 4252 Albania-NGN 1.085 355 422 Albania-Tirana 0.3864 355 423 Albania-Tirana 0.3864 355 424 Albania-Tirana 0.3864 213 Algeria 0.196 213 21 Algeria-Algiers 0.182 213 1 Algeria-CAT 0.196 213 6 Algeria-Mobile AMN 0.924 213 7 Algeria-Mobile Orascom 1.0251 213 5 Algeria-Mobile Wataniya 1.3629 1 684 American Samoa 0.1046 1 6842 American Samoa-Mobile 0.1046 376 Andorra 0.0654 376 3 Andorra-Mobile 0.5558 376 4 Andorra-Mobile 0.5558 376 6 Andorra-Mobile 0.5558 244 Angola 0.2859 244 9 Angola-Mobile 0.2891 1 264 Anguilla 0.3325 1 264235 Anguilla-Mobile CW 1.0955 Updated: April 2017 Page 1 of 236 1 264469 Anguilla-Mobile CW 1.0955 1 264476 Anguilla-Mobile CW 1.0955 1 264729 Anguilla-Mobile CW 1.0955 1 264772 Anguilla-Mobile CW 1.0955 1 26458 Anguilla-Mobile Digicel 1.225 1 264536 Anguilla-Mobile Weblinks 1.225 1 264537 Anguilla-Mobile Weblinks 1.225 1 264538 Anguilla-Mobile Weblinks 1.225 -

Vimpelcom Megafon 2906

Success story High quality local training helps Russian operators boost network performance 02/04 High quality local training helps Russian operators boost network performance Nokia Siemens Networks is committed to high quality training of operators’ staff to help them achieve the effective network operations that are vital in delivering subscriber satisfaction. We also strive to provide training as locally as possible. A new center in Moscow is bringing training closer to Russia’s mobile operators, making it easier and more convenient for them to get the training they need. VimpelCom launched its first and different levels is very good. commercial cellular network in We have the ability to choose Moscow in June 1994 with one particular training matched to our switch and 10 base stations. engineers’ needs. In general, As of April 2007, it operated in the quality is perfect”, says Andrey 78 regions of Russia, with more Gurlenov, Head of Technical Training than 100 switches and about for Beeline University. 20,000 base stations serving more than 57,5 million subscribers. Gurlenov also appreciates the report evaluation forms and statistics that MegaFon, the first all-Russian Nokia Siemens Networks sends mobile operator in the GSM every month, enabling him to assess 900/1800 standard, covers the the success of training. entire territory of the Russian Federation with a population of over “Although it is difficult to evaluate 145 million. Its extensive services accurately the impact of good are targeted at both individual and training in terms of rate of equipment corporate subscribers. failures or other measures, it is clear Andrey Gurlenov, that training is connected to network Head of Technical Training for Beeline University With such rapid expansion, both performance,” believes Gurlenov. -

Megafon Investor Presentation

MegaFon Investor presentation Morgan Stanley European TMT Conference 16-18 November Disclaimer Certain statements and/or other information included in this document may not be historical facts and may constitute “forward looking statements” within the meaning of Section 27A of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933 and Section 2(1)(e) of the U.S. Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. The words “believe”, “expect”, “anticipate”, “intend”, “estimate”, “plans”, “forecast”, “project”, “will”, “may”, “should” and similar expressions may identify forward looking statements but are not the exclusive means of identifying such statements. Forward looking statements include statements concerning our plans, expectations, projections, objectives, targets, goals, strategies, future events, future revenues, operations or performance, capital expenditures, financing needs, our plans or intentions relating to the expansion or contraction of our business as well as specific acquisitions and dispositions, our competitive strengths and weaknesses, the risks we face in our business and our response to them, our plans or goals relating to forecasted production, reserves, financial position and future operations and development, our business strategy and the trends we anticipate in the industry and the political, economic, social and legal environment in which we operate, and other information that is not historical information, together with the assumptions underlying these forward looking statements. By their very nature, forward looking statements involve inherent risks, uncertainties and other important factors that could cause our actual results, performance or achievements to be materially different from results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Such forward-looking statements are based on numerous assumptions regarding our present and future business strategies and the political, economic, social and legal environment in which we will operate in the future. -

Russian Advocacy Coalitions

Russian Advocacy Coalitions A study in Power Resources This study examines the advocacy coalitions in Russia. Using the Advocacy Coalition Framework, it looks at the power resource distribution amongst the coalitions, and how this distribution affects Russian foreign policy. The power resources examined are: Formal Legal Authority; Public Opinion; Information; Mobilizable Troops; and Financial Resources. In addition to this, the study used quantitative and qualitative methods to identify these resources. There are a couple of conclusions we may draw from this study. The method is useful in identifying power resources. It is not enough to use only the distribution of resources amongst coalitions in order to explain policy changes. It is found that the distribution of resources, coupled with coalition interaction, is enough to explain changes in Russian foreign policy. KEYWORDS: Advocacy Coalition Framework, Russia, Power Resources, Natural Gas WORDS: 24,368 Author: Robert Granlund Supervisor: Fredrik Bynander Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 PURPOSE .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 RESEARCH QUESTIONS ............................................................................................................ 2 1.3 OUTLINE.................................................................................................................................. -

Telecoms 150 2020

Telecoms 150 2020The annual report on the most valuable and strongest telecom brands April 2020 Contents. About Brand Finance 4 Get in Touch 4 Brandirectory.com 6 Brand Finance Group 6 Foreword 8 Brand Value Analysis 10 Regional Analysis 16 Brand Strength Analysis 18 Brand Finance Telecoms Infrastructure 10 20 Sector Reputation Analysis 22 Brand Finance Telecoms 150 (USD m) 24 Definitions 28 Brand Valuation Methodology 30 Market Research Methodology 31 Stakeholder Equity Measures 31 Consulting Services 32 Brand Evaluation Services 33 Communications Services 34 Brand Finance Network 36 brandirectory.com/telecoms Brand Finance Telecoms 150 April 2020 3 About Brand Finance. Brand Finance is the world's leading independent brand valuation consultancy. Request your own We bridge the gap between marketing and finance Brand Value Report Brand Finance was set up in 1996 with the aim of 'bridging the gap between marketing and finance'. For more than A Brand Value Report provides a 20 years, we have helped companies and organisations of all types to connect their brands to the bottom line. complete breakdown of the assumptions, data sources, and calculations used We quantify the financial value of brands We put 5,000 of the world’s biggest brands to the test to arrive at your brand’s value. every year. Ranking brands across all sectors and countries, we publish nearly 100 reports annually. Each report includes expert recommendations for growing brand We offer a unique combination of expertise Insight Our teams have experience across a wide range of value to drive business performance disciplines from marketing and market research, to and offers a cost-effective way to brand strategy and visual identity, to tax and accounting. -

Megafon Mobile Network in Moscow Area Brings Exciting Multimedia Messaging Services to Consumers with Nokia Solution

Source: Nokia Oyj October 07, 2002 05:00 ET MegaFon mobile network in Moscow area brings exciting multimedia messaging services to consumers with Nokia solution Nokia is delivering its leading Multimedia Messaging (MMS) solution to ZAO Sonic Duo, which operates in the Moscow area for Russian nationwide mobile network MegaFon. With the Nokia solution MegaFon's customers will be able to enjoy mobile images, sound and text. Deliveries begin during October 2002 and service is expected to be launched in first quarter 2003. The deal further enhances Nokia's track record in MMS - among the wireless industry's most extensive. With over 30 customers to date and an ever-growing number of launched systems, Nokia is helping to make multimedia messaging a reality for today's mobile consumers. "Nokia's vision and ability to provide tailor-made solutions and services proved very attractive to us and we enter this new business segment and move forward toward next-generation services," says Alexey Nichiporenko, General Director, Sonic Duo. "We are always looking for innovative new services and applications to offer our customers in the Capital and MMS is certain to be a big hit," adds Alexey Nichiporenko. The Nokia MMS solution gives mobile subscribers the ability enjoy multimedia services such as content access and person-to-person mobile messaging from MMS-capable handset to e-mail, e-mail to MMS handset or between applications and MMS handsets. The deal comes after Nokia announced on October 1 2002, that it will deliver the Nokia GPRS and MMS solutions to Megafon in the St.