View Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting to Know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE FOUR ORDERS: BOOK EXCERPT Getting to know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism hundreds ofyears that the four main been codified by Tibetan intellectual historians, who categorize Buddha's teachings in terms of three distinct of Tibetan Buddhism — Nyingma, vehicles — the Lesser Vehicle (Hinayana), the Great Vehicle akya, and Gelug — have evolved out of (Mahayana), and the Vajra Vehicle (Vajrayana) — each of which was intended to appeal to the spiritual capacities of their common roots in India, a wide array of particular groups. divergent practices, beliefs, and rituals have • Hinayana was presented to people intent on personal salvation in which one transcends come into being. However, there are signifi- suffering and is liberated from cyclic existence. • The audience of Mahayana teachings included cant underlying commonalities between the trainees with the capacity to feel compassion for different traditions, such as the importance the sufferings of others who wished to seek awakening in order to help sentient beings over- of overcoming attachment to the phenomena come their sufferings. of cyclic existence, and the idea that it is • Vajrayana practitioners had a strong interest in the welfare of others, coupled with determination necessary for trainees to develop an attitude to attain awakening as quickly as possible, and the spiritual capacity to pursue the difficult practices of sincere renunciation. John Powers' fasci- of tantra. nating and comprehensive book, Introduction Indian Buddhism is also commonly divided by scholars of the four Tibetan orders into four main schools of tenets to Buddhism, re-issued by Snow Lion in — Great Exposition School, Sutra School, Mind Only School, September 2007, contains a lucid explanation and Middle Way School. -

Under Memberships

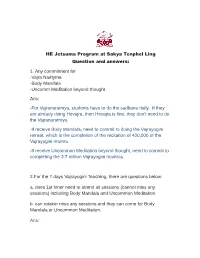

HE Jetsuma Program at Sakya Tenphel Ling Question and answers: 1. Any commitment for -Vajra Nairtyma -Body Mandala -Uncomm Meditation beyond thought Ans: -For Vajranaratmya, students have to do the sadhana daily. If they are already doing Hevajra, then Hevajra is fine, they don’t need to do the Vajranaratmya. -If receive Body Mandala, need to commit to doing the Vajrayogini retreat, which is the completion of the recitation of 400,000 of the Vajrayogini mantra. -If receive Uncommon Meditation beyond thought, need to commit to completing the 3.7 million Vajrayogini mantras. 2.For the 7 days Vajrayogini Teaching, there are questions below: a. does 1st timer need to attend all sessions (cannot miss any sessions) including Body Mandala and Uncommon Meditation. b. can retaker miss any sessions.and they can come for Body Mandala or Uncommon Meditation. Ans: a. Students who want to receive the proper transmission should attend all the sessions. However, if they don’t wish to receive the commitments of retreat and mantra accumulation (3.7 million), as is required if receive the body mandala and uncommon meditation beyond thought, they can skip those relevant sessions. b. For old timers who received the entire set before, it is their choice. However, Jetsun Kushok thinks it is beneficial to receive the teachings in its entirety without selectively choosing and skipping. 3.a For those new ones who.has taken 2 days Vajra Nairatyma empowerment, can they continue to take Vajrayogini Chin Lab and then go to the 7 days teaching? b. For those who.have taken 2 days Hevajra cause empowerment, they can come for Vajra Nairatyma empowerment and no need be one of the 25 new takers. -

Women in Cambodia – Analysing the Role and Influence of Women in Rural Cambodian Society with a Special Focus on Forming Religious Identity

WOMEN IN CAMBODIA – ANALYSING THE ROLE AND INFLUENCE OF WOMEN IN RURAL CAMBODIAN SOCIETY WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON FORMING RELIGIOUS IDENTITY by URSULA WEKEMANN submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY in the subject MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR D C SOMMER CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF R W NEL FEBRUARY 2016 1 ABSTRACT This study analyses the role and influence of rural Khmer women on their families and society, focusing on their formation of religious identity. Based on literature research, the role and influence of Khmer women is examined from the perspectives of history, the belief systems that shape Cambodian culture and thinking, and Cambodian social structure. The findings show that although very few Cambodian women are in high leadership positions, they do have considerable influence, particularly within the household and extended family. Along the lines of their natural relationships they have many opportunities to influence the formation of religious identity, through sharing their lives and faith in words and deeds with the people around them. A model based on Bible storying is proposed as a suitable strategy to strengthen the natural influence of rural Khmer women on forming religious identity and use it intentionally for the spreading of the gospel in Cambodia. KEY WORDS Women, Cambodia, rural Khmer, gender, social structure, family, religious formation, folk-Buddhism, evangelization. 2 Student number: 4899-167-8 I declare that WOMEN IN CAMBODIA – ANALYSING THE ROLE AND INFLUENCE OF WOMEN IN RURAL CAMBODIAN SOCIETY WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON FORMING RELIGIOUS IDENTITY is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. -

Chapter II * Place of Hevajra Tantraj in Tantric Literature

Chapter II * Place of Hevajra Tantraj in Tantric Literature 4 1. Buddhist Tantric Literature Lama Anagarik Govinda wrote: “the word ‘Tantrd is related to the concept of weaving and its derivatives (thread, web, fabric, etc.), hinting at the interwovenness of things and actions, the interdependence of all that exists, the continuity in the interaction of cause and effect, as well as in spiritual and'traditional development, which like a thread weaves its way through the fabric of history and of individual lives. The scriptures which in Buddhism go under the name of Tantra (Tib.: rgyud) are invariably of a mystic nature, i.e., trying to establish the inner relationship of things: the parallelism of microcosm and macrocosm, mind and universe, ritual and reality, the world of matter and the world of the spirit.”99 Scholars like N.N. Bhattacharyya and also Pranabananda Jash, regard Tantra as a religious system or science (Sastra) dealing with the means (sadhana) of attaining success (siddhi) in secular or religious efforts.100 N.N. Bhattacharyya mentions that “Tantra came to mean the essentials of any religious system and, subsequently, special doctrines and rituals found only in certain forms of various religious systems. This change in the meaning, significance, and character of the word ‘Tantra' is quite striking and is likely to reveal many hitherto unnoticed elements that have characterised the social fabric of India through the ages.”101 It is must be noted that the Tantrika tradition is not the work of a day, it has a long history behind it. Creation, maintenance and dissolution, 99 Lama Anagarika Govinda, Foundations of Tibetan Myticism (Maine: Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1969), p.93. -

Chinese and Tibetan Tantric Buddhism

THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM THE ISRAEL INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES International Research Conference of the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies (IIAS) and the Israel Science Foundation with additional support from the Louis Freiberg Center for East Asian Studies and the Confucius Institute, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem CHINESE AND TIBETAN TANTRIC BUDDHISM June 16-18, 2014 All lectures will take place at the Feldman Building, on the Edmond J. Safra, Givat Ram Campus, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Organizers: Yael Bentor (The Hebrew University) Meir Shahar (Tel Aviv University) PROGRAM Monday, June 16 9:30 Gathering 10:00 Greetings: Michal Linial (Director, IIAS) 10:30-12:00 ESOTERIC BUDDHISM AND CHINESE RELIGION Robert H. Sharf (University of California, Berkeley) Esoteric Buddhist Influence on the Emergence of Chan in Eighth Century China Meir Shahar (Tel Aviv University & IIAS) The Tantric Origins of the Horse King: Hayagrīva and the Chinese Horse Cult Vincent Durand-Dastès (INALCO, Centre d’études chinoises, Equipe ASIEs, Paris) Esoteric Buddhism, Violence and Salvation in Ming-Qing Vernacular Novels 12:00-13:30 Lunch break 13:30-15:00 TIBETAN TANTRIC SCRIPTURES Jacob P. Dalton (University of California, Berkeley) Observations on the Ārya-tattvasaṃgraha-sādhanopāyikā and Its Commentary from Dunhuang Yael Bentor (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem & IIAS) Conflicting Positions over the Interpretation of the Body Maṇḍala Jampa Samten (Central University for Tibetan Studies, Varanasi & IIAS) The Secret Signs (Chommaka) -

A STUDY of the NAMES of MONUMENTS in ANGKOR (Cambodia)

A STUDY OF THE NAMES OF MONUMENTS IN ANGKOR (Cambodia) NHIM Sotheavin Sophia Asia Center for Research and Human Development, Sophia University Introduction This article aims at clarifying the concept of Khmer culture by specifically explaining the meanings of the names of the monuments in Angkor, names that have existed within the Khmer cultural community.1 Many works on Angkor history have been researched in different fields, such as the evolution of arts and architecture, through a systematic analysis of monuments and archaeological excavation analysis, and the most crucial are based on Cambodian epigraphy. My work however is meant to shed light on Angkor cultural history by studying the names of the monuments, and I intend to do so by searching for the original names that are found in ancient and middle period inscriptions, as well as those appearing in the oral tradition. This study also seeks to undertake a thorough verification of the condition and shape of the monuments, as well as the mode of affixation of names for them by the local inhabitants. I also wish to focus on certain crucial errors, as well as the insufficiency of earlier studies on the subject. To begin with, the books written in foreign languages often have mistakes in the vocabulary involved in the etymology of Khmer temples. Some researchers are not very familiar with the Khmer language, and besides, they might not have visited the site very often, or possibly also they did not pay too much attention to the oral tradition related to these ruins, a tradition that might be known to the village elders. -

Self-Initiation Text

The Quick Path to Great Bliss: The Uncommon Sadhana of Venerable Vajrayogini Naro Khechari Together with the Self-Initiation Ritual, The Mandala Rite, Banquet of Great Bliss Arranged Simply and Clearly for the Sake of Easy Verbal Recitation Even if you have received [a highest yoga tantra] initiation and the blessing [initiation] of Vajrayogini, if you have not received the profound instructions on the two stages, refrain from reading this. With great respect, I prostrate to the feet of the guru, inseparable from Venerable Vajrayogini. With your great compassion, please care for me. A. Prepara@on Yogas 1, 2, and 3 To start, perform the first yoga of sleeping, the second yoga of waking, and the third yoga of tas@ng nectar. 4. Yoga of Immeasurables Sit with the physical essen@als [of the seven-fold posture] and recite: Dün gyi nam khar la ma khor lo dom pa yab yum la tsa gyü kyi la ma yi dam chhog sum ka dö sung mäi tshog kyi kor nä zhug par gyur In the space before me are Guru Chakrasamvara father and mother, encircled by the assemblies of root and lineage gurus, yidams, the Three Jewels, Dharma protectors, and guardians. Taking Refuge Imagine yourself and all sen@ent beings going for refuge: Dag dang dro wa nam khäi tha dang nyam päi sem chän tham chä dü di nä zung te ji si jang chhub nying po la chhi kyi bar du I and all living beings, equaling the limits of space, from now unAl reaching the essence of enlightenment, Päl dän la ma dam pa nam la kyab su chhi o Go for refuge to the glorious holy gurus; Dzog päi sang gyä chom dän dä nam la kyab su chhi o We go for refuge to the complete buddha bhagavans; Dam päi chhö nam la kyab su chhi o We go for refuge to the holy Dharma; Phag päi gen dün nam la kyab su chhi o (3x) We go for refuge to the arya Sangha. -

{Download PDF} the Last King of Angkor

THE LAST KING OF ANGKOR WAT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graeme Base | 36 pages | 16 Sep 2014 | Abrams Books For Young Readers | 9781419713545 | English | United States Angkor Wat | Description, Location, History, Restoration, & Facts | Britannica A foot metre bridge allows access to the site. The temple is reached by passing through three galleries, each separated by a paved walkway. The temple walls are covered with bas-relief sculptures of very high quality, representing Hindu gods and ancient Khmer scenes as well as scenes from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. When he built a new capital nearby, Angkor Thom, he dedicated it to Buddhism. Thereafter, Angkor Wat became a Buddhist shrine, and many of its carvings and statues of Hindu deities were replaced by Buddhist art. In the early 15th century Angkor was abandoned. Still Theravada Buddhist monks maintained Angkor Wat, which remained an important pilgrimage site and continued to attract European visitors. In the 20th century various restoration programs were undertaken, but they were suspended amid the political unrest that engulfed Cambodia in the s. When work resumed in the mids, the required repairs were extensive. Notably, sections had to be dismantled and rebuilt. In the ensuing years, restoration efforts increased, and Angkor was removed from the danger list in Today Angkor Wat is one of the most important pilgrimage shrines in Southeast Asia and a popular tourist attraction. The temple complex appears on the Cambodian flag. Print Cite. Facebook Twitter. Give Feedback External Websites. Let us know if you have suggestions to improve this article requires login. External Websites. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. -

A Brief Summary of the History of Hevajra in Cambodia

Spencer Ames 2/19/19 A Brief Summary of the History of Hevajra in Cambodia The Khmer kingdom (12th – 13th century): King Jayavarman VII and his Wife Indradevi. I first encountered the ruins of Cambodia’s ancient kingdoms on a family trip many years ago. My brother and I were climbing through thick vines and over giant tree roots entwining ancient carved stones. There were Buddha images throughout the intricately carved ruins, most of them decapitated or worn down to being almost unrecognizable by time and the overgrown jungle. I was a Buddhist myself and these ruins spoke to me at a deep level. My little bit of research at that time into these amazing ruins hinted that the Mahayana and Vajrayana were once practiced there. Twelve years passed and I found myself about to move to Cambodia for a year, and my initial curiosity was sparked again. While living there I dove into whatever research I could find on ancient and modern Buddhism in Cambodia and discovered a surprising link to my own Drikung Kagyu Tibetan Buddhist lineage. In the 12-13th century in Cambodia, and perhaps up to a few centuries before that, the Heruka tantras of Hevajra and Chakrasamvara made their way to the Khmer kingdom in Cambodia. There is little information that has survived to the present from these Vajrayana lineages, due to the secret nature of the teachings, and later to a nearly complete suppression and destruction of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism by successive Hinayana, Hindu and Communist rulers. The small amount of information we do know primarily comes to us from the time of King Jayavarman VII (1125–1218 AD) who is generally considered Cambodia’s most famous and powerful king. -

Readingsample

Contributions to Tibetan Studies 6 Hevajra and Lam’bras Literature of India and Tibet as Seen Through the Eyes of A-mes-zhabs Bearbeitet von Jan-Ulrich Sobisch 1. Auflage 2008. Buch. ca. 264 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 89500 652 4 Format (B x L): 17 x 24 cm Gewicht: 616 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Religion > Buddhismus > Tibetischer Buddhismus Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. General introduction to the transmission of the Hevajra teachings In the following, I would like to provide an introduction to this study of the Hevajra teachings (and subsequent to that to the Path with Its Fruit teachings) that is accessible to both those who do read the Tibetan language and those who do not. I have therefore abstained in these two introductory chapters from using the regular Wylie transliteration of Tibetan names, and I have translated an abbreviated form of all titles of Tibetan works mentioned. I am sure that all names, which I have rendered here in an approximate phonetic transliteration, will be easily recognizable to the expert. To ensure, furthermore, the expert’s recognition of the translated titles of works, I have added the Tibetan abbreviated form of titles in Wylie transcription in brackets. For all bibliographical references, please refer to the main part of the book. -

Medieval Khmer Society: the Life and Times of Jayavarman VII (Ca

John Carroll University Carroll Collected 2019 Faculty Bibliography Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage 2019 Medieval Khmer Society: The Life and Times of Jayavarman VII (ca. 1120–1218) Paul K. Nietupski John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2019 Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the Hindu Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nietupski, Paul K., "Medieval Khmer Society: The Life and Times of Jayavarman VII (ca. 1120–1218)" (2019). 2019 Faculty Bibliography. 34. https://collected.jcu.edu/fac_bib_2019/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Bibliographies Community Homepage at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2019 Faculty Bibliography by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Article How to Cite: Nietupski, Paul. 2019. Medieval Khmer Society: The Life and Times of Jayavarman VII (ca. 1120–1218). ASIANetwork Exchange, 26(1), pp. 33–74. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/ane.280 Published: 19 June 2019 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of ASIANetwork Exchange, which is a journal of the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: ASIANetwork Exchange is a peer-reviewed open access journal. -

Archaeology Unit Archaeology Report Series

#8 NALANDA–SRIWIJAYA CENTRE ARCHAEOLOGY UNIT ARCHAEOLOGY REPORT SERIES Tonle Snguot: Preliminary Research Results from an Angkorian Hospital Site D. KYLE LATINIS, EA DARITH, KÁROLY BELÉNYESY, AND HUNTER I. WATSON A T F Archaeology Unit 6870 0955 facebook.com/nalandasriwijayacentre Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute F W 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace, 6778 1735 Singapore 119614 www.iseas.edu.sg/centres/nalanda-sriwijaya-centre E [email protected] The Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre Archaeology Unit (NSC AU) Archaeology Report Series has been established to provide an avenue for publishing and disseminating archaeological and related research conducted or presented within the Centre. This also includes research conducted in partnership with the Centre as well as outside submissions from fields of enquiry relevant to the Centre's goals. The overall intent is to benefit communities of interest and augment ongoing and future research. The NSC AU Archaeology Report Series is published Citations of this publication should be made in the electronically by the Nalanda–Sriwijaya Centre of following manner: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. Latinis, D. K., Ea, D., Belényesy, K., and Watson, H. I. (2018). “Tonle Snguot: Preliminary Research Results from an © Copyright is held by the author/s of each report. Angkorian Hospital Site.” Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Archaeology Unit Archaeology Report Series No. 8. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute accepts no responsibility for facts presented and views expressed. Responsibility Cover image: Natalie Khoo rests exclusively with the individual author or authors. Authors have agreed that permission has been obtained from appropriate sources to include any Editor : Foo Shu Tieng content in the publication such as texts, images, maps, Cover Art Template : Aaron Kao tables, charts, graphs, illustrations, and photos that are Layout & Typesetting : Foo Shu Tieng not exclusively owned or copyrighted by the authors.