Muscle Length of the Hamstrings Using Ultrasonography Versus Musculoskeletal Modelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hip Extensor Mechanics and the Evolution of Walking and Climbing Capabilities in Humans, Apes, and Fossil Hominins

Hip extensor mechanics and the evolution of walking and climbing capabilities in humans, apes, and fossil hominins Elaine E. Kozmaa,b,1, Nicole M. Webba,b,c, William E. H. Harcourt-Smitha,b,c,d, David A. Raichlene, Kristiaan D’Aoûtf,g, Mary H. Brownh, Emma M. Finestonea,b, Stephen R. Rossh, Peter Aertsg, and Herman Pontzera,b,i,j,1 aGraduate Center, City University of New York, New York, NY 10016; bNew York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology, New York, NY 10024; cDepartment of Anthropology, Lehman College, New York, NY 10468; dDivision of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024; eSchool of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; fInstitute of Ageing and Chronic Disease, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L7 8TX, United Kingdom; gDepartment of Biology, University of Antwerp, 2610 Antwerp, Belgium; hLester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes, Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago, IL 60614; iDepartment of Anthropology, Hunter College, New York, NY 10065; and jDepartment of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708 Edited by Carol V. Ward, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO, and accepted by Editorial Board Member C. O. Lovejoy March 1, 2018 (received for review September 10, 2017) The evolutionary emergence of humans’ remarkably economical their effects on climbing performance or tested whether these walking gait remains a focus of research and debate, but experi- traits constrain walking and running performance. mentally validated approaches linking locomotor -

Iliopsoas Tendonitis/Bursitis Exercises

ILIOPSOAS TENDONITIS / BURSITIS What is the Iliopsoas and Bursa? The iliopsoas is a muscle that runs from your lower back through the pelvis to attach to a small bump (the lesser trochanter) on the top portion of the thighbone near your groin. This muscle has the important job of helping to bend the hip—it helps you to lift your leg when going up and down stairs or to start getting out of a car. A fluid-filled sac (bursa) helps to protect and allow the tendon to glide during these movements. The iliopsoas tendon can become inflamed or overworked during repetitive activities. The tendon can also become irritated after hip replacement surgery. Signs and Symptoms Iliopsoas issues may feel like “a pulled groin muscle”. The main symptom is usually a catch during certain movements such as when trying to put on socks or rising from a seated position. You may find yourself leading with your other leg when going up the stairs to avoid lifting the painful leg. The pain may extend from the groin to the inside of the thigh area. Snapping or clicking within the front of the hip can also be experienced. Do not worry this is not your hip trying to pop out of socket but it is usually the iliopsoas tendon rubbing over the hip joint or pelvis. Treatment Conservative treatment in the form of stretching and strengthening usually helps with the majority of patients with iliopsoas bursitis. This issue is the result of soft tissue inflammation, therefore rest, ice, anti- inflammatory medications, physical therapy exercises, and/or injections are effective treatment options. -

The Effect of Stretching Hamstring, Gastrocnemius, Iliopsoas

Open Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 2015, 3, 139-145 Published Online November 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojtr http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojtr.2015.34019 The Effect of Stretching Hamstring, Gastrocnemius, Iliopsoas and Back Muscles on Pain and Functional Activities in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Hamada E. Seif1, Aqeel Alenazi2, Sahar Mahmoud Hassan1, Shaji John Kachanathu3, Ashraf R. Hafez1* 1Cairo UniversityHospital, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt 2Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Department, College of Applied Medical Sciences, Salman Bin Abdulaziz University, Alkharj, Saudi Arabia 3Collage of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Received 15 September 2015; accepted 6 November 2015; published 9 November 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract A back pain lasting more than 12 weeks has been defined as a chronic low back pain (LBP) [1]. More than half of people suffer from LBP [1]. The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of gastrocnemius muscle stretching in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Methods: Forty pa- tients with chronic low back pain, ages ranging from 25 to 40 years, were recruited and divided randomly into two groups. The control group followed a physical therapy program that included stretching exercises for back, hamstring and iliopsoas muscles. Strengthening exercises for abdo- minal muscle and postural instructions for activities of daily living were also performed. The ex- perimental group followed the same control-group exercises with the addition of stretching exer- cises for gastrocnemius muscles. -

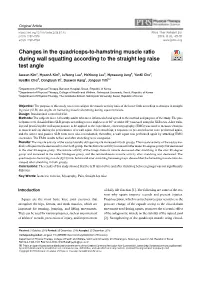

Changes in the Quadriceps-To-Hamstring Muscle

Original Article https://doi.org/10.14474/ptrs.2019.8.1.45 Phys Ther Rehabil Sci pISSN 2287-7576 2019, 8 (1), 45-51 eISSN 2287-7584 www.jptrs.org Changes in the quadriceps-to-hamstring muscle ratio http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.14474/ptrs.2019.8.1.45&domain=pdf&date_stamp=2019-3-25 during wall squatting according to the straight leg raise test angle Jaeeun Kima, HyeonA Kimb, JuYeong Leeb, HoYoung Leeb, Hyoseung Jungb, YunKi Chob, HyeMin Choib, Donghyun Yic, Daewon Kangc, Jongeun Yimb,c a Department of Physical Therapy, Barosun Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea b Department of Physical Therapy, College of Health and Welfare, Sahmyook University, Seoul, Republic of Korea c Department of Physical Therapy, The Graduate School, Sahmyook University, Seoul, Republic of Korea Objective: The purpose of this study was to investigate the muscle activity ratio of the lower limb according to changes in straight leg raise (SLR) test angles on hamstring muscle shortening during squat exercises. Design: Randomized controlled trial. Methods: The subjects were 14 healthy adults who were informed of and agreed to the method and purpose of the study. The par- ticipants were classified into SLR groups according to two angles (over 80° or under 80°) assessed using the SLR tests. After train- ing and practicing the wall squat posture to be applied to the experiment, electromyography (EMG) was used to measure changes in muscle activity during the performance of a wall squat. After stretching, a sequence of pre-stretch tests were performed again, and the active and passive SLR tests were also reconducted; thereafter, a wall squat was performed again by attaching EMG electrodes. -

Fundamentals of Biomechanics Duane Knudson

Fundamentals of Biomechanics Duane Knudson Fundamentals of Biomechanics Second Edition Duane Knudson Department of Kinesiology California State University at Chico First & Normal Street Chico, CA 95929-0330 USA [email protected] Library of Congress Control Number: 2007925371 ISBN 978-0-387-49311-4 e-ISBN 978-0-387-49312-1 Printed on acid-free paper. © 2007 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. 987654321 springer.com Contents Preface ix NINE FUNDAMENTALS OF BIOMECHANICS 29 Principles and Laws 29 Acknowledgments xi Nine Principles for Application of Biomechanics 30 QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS 35 PART I SUMMARY 36 INTRODUCTION REVIEW QUESTIONS 36 CHAPTER 1 KEY TERMS 37 INTRODUCTION TO BIOMECHANICS SUGGESTED READING 37 OF UMAN OVEMENT H M WEB LINKS 37 WHAT IS BIOMECHANICS?3 PART II WHY STUDY BIOMECHANICS?5 BIOLOGICAL/STRUCTURAL BASES -

Quadriceps and Hamstrings Coactivation in Exercises Used in Prevention And

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/574210; this version posted March 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Quadriceps and hamstrings coactivation in exercises used in prevention and 2 rehabilitation of hamstring strain injury in young soccer players 3 Gonzalo Torres1¶; David Chorro1¶; Archit Navandar2¶; Javier Rueda1¶; Luís 4 Fernández3¶; Enrique Navarro1*¶ 5 6 1Faculty of Sport Sciences, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Madrid, Spain. 7 2Faculty of Sport Sciences, Universidad Europea de Madrid, Madrid, Madrid, Spain. 8 3Medical Services of Atlético de Madrid, Club Atlético de Madrid, Madrid, Madrid, 9 Spain. 10 11 12 *Corresponding author 13 E-mail: [email protected] (EN) 14 15 ¶These authors contributed equally to this work. 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/574210; this version posted March 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 25 Abstract 26 This study aimed to study the co-activation of hamstring-quadriceps muscles 27 during submaximal strength exercises without the use of maximum voluntary isometric 28 contraction testing and compare (i) the inter-limb differences in muscle activation, (ii) the 29 intra-muscular group activation pattern, and (iii) the activation during different phases of 30 the exercise. -

The Volume and Distribution of Blood in the Human Leg Measured in Vivo. I. the Effects of Graded External Pressure

THE VOLUME AND DISTRIBUTION OF BLOOD IN THE HUMAN LEG MEASURED IN VIVO. I. THE EFFECTS OF GRADED EXTERNAL PRESSURE Julius Litter, J. Edwin Wood J Clin Invest. 1954;33(5):798-806. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI102951. Research Article Find the latest version: https://jci.me/102951/pdf THE VOLUME AND DISTRIBUTION OF BLOOD IN THE HUMAN LEG MEASURED IN VIVO. I. THE EFFECTS OF GRADED EXTERNAL PRESSURE 1, 2 By JULIUS LITTER AND J. EDWIN WOOD (From the Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine and the Evans Memorial, Massachusetts Memorial Hospitals, Boston, Mass.) (Submitted for publication July 1, 1953; accepted January 27, 1954) Venous pressure-volume curves obtained by ve- sumption that the volume of a blood vessel varies nous congestion may be useful for the study of ve- directly with the effective intravascular pressure, nous tone in human extremities. However, such if other factors are controlled. This assumption pressure-volume curves should be measured from has been thoroughly validated by Ryder, Molle, and a constant reference point or baseline of venous Ferris using isolated veins (6). volume and effective venous pressure. The purpose of this paper is to show that such a APPARATUS constant baseline is obtained when an external The water plethysmograph (Figure 1) described by pressure equal to or greater than the natural local Wilkins and Eichna (7) was modified at the open ends venous pressure is applied to the leg. This has by replacing the rubber diaphragms (formerly cemented to the skin) with a loose-fitting, thin rubber sleeve (8). been demonstrated by measuring the volume of The ends of the sleeve were everted and permanently sealed blood in the human leg, in vivo, at graded external to the flanges at each end of the plethysmograph. -

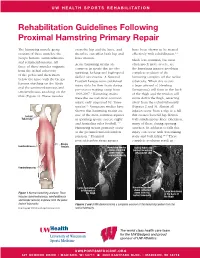

Rehabilitation Guidelines Following Proximal Hamstring Primary Repair

UW HEALTH SPORTS REHABILITATION Rehabilitation Guidelines Following Proximal Hamstring Primary Repair The hamstring muscle group cross the hip and the knee, and have been shown to be treated consists of three muscles: the therefore can affect both hip and effectively with rehabilitation.1, 8 biceps femoris, semitendinosus knee motion. Much less common, but most and semimembranosus. All Acute hamstring strains are often much more severe, are three of these muscles originate common in sports that involve the hamstring injuries involving from the ischial tuberosity sprinting, kicking and high-speed complete avulsion of the of the pelvis and then insert skilled movements. A National hamstring complex off the ischial below the knee with the biceps Football League team published tuberosity. When this occurs femoris attaching on the fibula injury data for their team during a large amount of bleeding and the semimembranosus and pre-season training camp from (hematoma) will form in the back semitendinosus attaching on the 1998-2007.1 Hamstring strains of the thigh and the tendon will tibia (Figure 1). These muscles were the second most common move down the thigh, retracting injury, only surpassed by “knee away from the ischial tuberosity sprains”.1 Numerous studies have (Figures 2 and 3). Almost all shown that hamstring strains are injuries occur from a slip or a fall Ischial one of the most common injuries that creates forceful hip flexion Tuberosity in sprinting sports, soccer, rugby with simultaneous knee extension, and Australian rules football.1-12 -

Hamstring Muscle Injuries

DISEASES & CONDITIONS Hamstring Muscle Injuries Hamstring muscle injuries — such as a "pulled hamstring" — occur frequently in athletes. They are especially common in athletes who participate in sports that require sprinting, such as track, soccer, and basketball. A pulled hamstring or strain is an injury to one or more of the muscles at the back of the thigh. Most hamstring injuries respond well to simple, nonsurgical treatments. Anatomy The hamstring muscles run down the back of the thigh. There are three hamstring muscles: Semitendinosus Semimembranosus Biceps femoris They start at the bottom of the pelvis at a place called the ischial tuberosity. They cross the knee joint and end at the lower leg. Hamstring muscle fibers join with the tough, connective tissue of the hamstring tendons near the points where the tendons attach to bones. The hamstring muscle group helps you extend your leg straight back and bend your knee. Normal hamstring anatomy. The three hamstring muscles start at the bottom of the pelvis and end near the top of the lower leg. Description A hamstring strain can be a pull, a partial tear, or a complete tear. Muscle strains are graded according to their severity. A grade 1 strain is mild and usually heals readily; a grade 3 strain is a complete tear of the muscle that may take months to heal. Most hamstring injuries occur in the thick, central part of the muscle or where the muscle fibers join tendon fibers. In the most severe hamstring injuries, the tendon tears completely away from the bone. It may even pull a piece of bone away with it. -

A Thesis Entitled Relationship Between Hamstring Strength And

A Thesis entitled Relationship Between Hamstring Strength and Agonist-Antagonist Co-Activation by Meghan Gregoire Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Exercise Science with a Concentration in Athletic Training ___________________________________________ Grant Norte, PhD, AT, ATC, CSCS, Committee Chair ___________________________________________ Neal Glaviano, PhD, AT, ATC, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Amanda Murray, PT, DPT, PhD, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Lucinda Bouillon, PT, DPT, PhD, Committee Member ___________________________________________ Cyndee Gruden, PhD, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo May 2019 Copyright 2019, Meghan Gregoire This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of Relationship Between Hamstring Strength and Agonist-Antagonist Co-Activation by Meghan Gregoire Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Exercise Science The University of Toledo May 2019 Introduction: Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury is common among females due to several neuromuscular risk factors. Decreased hamstrings to quadriceps (H:Q) ratio is one neuromuscular factor that place females at an increased risk of ACL injury. Increased activation of the hamstrings during functional tasks help assist the static stabilizes of the knee, decrease strain on the ACL and reduce anterior tibial translation. Objectives: The objective of this study was to (1) identify the relationship between H:Q strength and co- activation ratio in the medial and lateral compartments of the knee during the stance phase of walking gait as well as (2) compare H:Q ratio between high and low groups. -

Anatomical Variation of the Semitendinosus Muscle Origin

eISSN 1308-4038 International Journal of Anatomical Variations (2013) 6: 225–227 Case Report Anatomical variation of the semitendinosus muscle origin Published online December 28th, 2013 © http://www.ijav.org Patrick Richard FRASER Abstract Addison Reed WOOD During a routine dissection of an 87-year-old female cadaver, an aberrant muscle attachment (AMA) of the right semitendinosus (ST) muscle origin was discovered medial to the primary Armando Aviles ROSALES muscle origin. This attachment originated from the medial portion of the ischial tuberosity and inferior to the sacrotuberous ligament attachment site. It then traveled distally in the long axis Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, University of of the femur to join the ST muscle, which showed no other variations in structure. Variation in hamstring muscle origins has been shown to predispose patients to hamstring strains and North Texas Health Science Center, 3500 Camp Bowie posterior thigh pain. This study describes a previously undocumented variation of the ST Boulevard, Fort Worth, Texas, 76107-2699, USA. origin that could predispose a patient to the aforementioned thigh pain, as well as pelvic floor pain. Patients presenting with recurrent pain or dysfunction in these areas should prompt an investigation into possible variations of hamstring muscle origins. Armando Rosales, MD © Int J Anat Var (IJAV). 2013; 6: 225–227. Department of Cell Biology & Anatomy University of North Texas Health Science Center 3500 Camp Bowie Boulevard Fort Worth, TX 76107-2699, USA. +1 (817) 735-2032 [email protected] Received February 26th, 2013; accepted August 22nd, 2013 Key words [semitendinosus] [variation] [strain] [hamstring] [muscle] Introduction 2). -

Analysis of Reaction Forces in Human Ankle Joint During Gait

MATEC Web of Conferences 112, 07019 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/matecconf/20171120701 9 IManE&E 2017 Analysis of reaction forces in human ankle joint during gait Daniel Ganea, Elena Mereuta, Silvia Veresiu, Madalina Rus, and Valentin Amortila* “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati, Department of Mechanical Engineering, 111 Domnească Street, Romania Abstract. The paper aims to analyze the human ankle joint reaction forces with a multibody system approach, using MSC Adams software and its features. The paper presents the results provided by the simulation of a spatial mechanical structure, which replicates the human’s locomotion system in terms of bone structure. The mechanical structure used for determining the human ankle joint reaction forces consists of 7 kinematic elements linked by 6 spherical joints constrained to 1 DOF each. 1 Introduction The study of joints forces in human body joints is extremely important for physiotherapists, coaches and athletes. It is often difficult to determine these internal forces using noninvasive methods. However, the inverse dynamics analysis can provide with good approximation the forces in human joints. While direct dynamics is used for determining how human body actuators are used, the inverse dynamic analysis is widely used in estimating joints moments and reaction forces [1, 2]. Using the inverse dynamics approach in human body motion analysis the computational effort is considerable reduced by avoiding the numerical integration of state equations. Unfortunately, the approach is poorly explored in biomechanics [2, 3]. The same method was use by some authors to estimate the force developed by human body actuators [4]. They have used a multibody model with 5 degrees of freedom.