ETHICS of SEEING – Paper Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Europe

NAZI PLANS for EASTE RN EUR OPE A Study of Lebensraum Policies SECRET NAZI PLANS for EASTERN EUROPE A Study of Lebensraum Policies hy Ihor Kamenetsky ---- BOOKMAN ASSOCIATES :: New York Copyright © 1961 by Ihor Kamenetsky Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 61-9850 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY UNITED PRINTING SERVICES, INC. NEW HAVEN, CONN. TO MY PARENTS Preface The dawn of the twentieth century witnessed the climax of imperialistic competition in Europe among the Great Pow ers. Entrenched in two opposing camps, they glared at each other over mountainous stockpiles of weapons gathered in feverish armament races. In the one camp was situated the Triple Entente, in the other the Triple Alliance of the Central Powers under Germany's leadership. The final and tragic re sult of this rivalry was World War I, during which Germany attempted to realize her imperialistic conception of M itteleuropa with the Berlin-Baghdad-Basra railway project to the Near East. Thus there would have been established a transcontinental highway for German industrial and commercial expansion through the Persian Gull to the Asian market. The security of this highway required that the pressure of Russian imperi alism on the Middle East be eliminated by the fragmentation of the Russian colonial empire into its ethnic components. Germany· planned the formation of a belt of buffer states ( asso ciated with the Central Powers and Turkey) from Finland, Beloruthenia ( Belorussia), Lithuania, Poland to Ukraine, the Caucasus, and even to Turkestan. The outbreak and nature of the Russian Revolution in 1917 offered an opportunity for Imperial Germany to realize this plan. -

German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Germany on Their Minds”? German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Anne Clara Schenderlein Committee in charge: Professor Frank Biess, Co-Chair Professor Deborah Hertz, Co-Chair Professor Luis Alvarez Professor Hasia Diner Professor Amelia Glaser Professor Patrick H. Patterson 2014 Copyright Anne Clara Schenderlein, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Anne Clara Schenderlein is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii Dedication To my Mother and the Memory of my Father iv Table of Contents Signature Page ..................................................................................................................iii Dedication ..........................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................v -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Arani, Miriam Y. "Photojournalism As a Means of Deception in Nazi-Occupied Poland, 1939– 45." Visual Histories of Occupation: a Transcultural Dialogue

Arani, Miriam Y. "Photojournalism as a means of deception in Nazi-occupied Poland, 1939– 45." Visual Histories of Occupation: A Transcultural Dialogue. Ed. Jeremy E. Taylor. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 159–182. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 23 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350167513.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 23 September 2021, 13:56 UTC. Copyright © Jeremy E. Taylor 2021. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 7 Photojournalism as a means of deception in Nazi-occupied Poland, 1939–45 Miriam Y. Arani Introduction Outside Europe, the conflicting memories of Germans, Poles and Jews are hard to understand. They are informed by conflicts before and during the Second World War. In particular, the impact of Nazism in occupied Poland (1939–45) – including the Holocaust – is difficult to understand without considering the deceitful propaganda of Nazism that affected visual culture in a subliminal but crucial way. The aim of this chapter is to understand photographs of the Nazi occupation of Poland as visual artefacts with distinct meanings for their contemporaries in the framework of a specific historical and cultural context. I will discuss how Nazi propaganda deliberately exploited the faith in still photography as a neutral depiction of reality, and the extent of that deceit through photojournalism by the Nazi occupiers of Poland. In addition, I will outline methods through which to evaluate the reliability of photographic sources. For the purposes of reliability and validity, I use a large, randomized sample with all kinds of photographs from archives, libraries and museums in this study. -

Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1

* pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. These films shed light on the way Ger- many chose to remember its recent past. A body of twenty-five films is analysed. For insight into the understanding and reception of these films at the time, hundreds of film reviews, censorship re- ports and some popular history books are discussed. This is the first rigorous study of these hitherto unacknowledged war films. The chapters are ordered themati- cally: war documentaries, films on the causes of the war, the front life, the war at sea and the home front. Bernadette Kester is a researcher at the Institute of Military History (RNLA) in the Netherlands and teaches at the International School for Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Am- sterdam. She received her PhD in History FilmFilm FrontFront of Society at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. She has regular publications on subjects concerning historical representation. WeimarWeimar Representations of the First World War ISBN 90-5356-597-3 -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00830-4

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00830-4 - The German Minority in Interwar Poland Winson Chu Index More information Index Agrarian conservativism, 71 Beyer, Hans Joachim, 212 Alldeutscher Verband. See Pan-German Bielitz. See Bielsko League Bielitzer Kreis, 174 Allgemeiner Schulverein, 36 Bielsko, 25, 173, 175, 203 Alltagsgeschichte, 10 Bielsko Germans, 108, 110, 111 Ammende, Ewald, 136 Bierschenk, Theodor, 137, 216, 224 Anschluß question, 51, 52 Bjork, James, 17 Anti-Communism, 165 Blachetta-Madajczyk, Petra, 9, 130, 136 Anti-Germanism, 214, 244, 245 Black Palm Sunday, 213–217 Anti-Semitism, 38, 79, 151, 159, 166, 178, Blanke, Richard, 9, 65, 76, 90, 136, 162 212, 215, 244, 260 Boehm, Max Hildebert, 31, 39, 46, 54, 88, Association for Germandom Abroad. See 97, 99, 110, 205 Verein fur¨ das Deutschtum im Ausland Border Germans and Germans Abroad, 44 Auslandsdeutsche, 98, 206.SeealsoReich Brackmann, Albert, 45, 208 Germans; Reich Germans, former Brauer, Leo, 221 Auslands-Organisation der NSDAP, 180, Brest-Litovsk Treaty, 42 205 Breuler, Otto, 103 Austria, 34, 165, 173, 207 Breyer, Albert, 153, 155, 212 annexation of, 51 Breyer, Richard, 155, 216, 272, 274 Austrian Silesia. See Teschen Silesia Briand, Aristide, 50 Bromberg. See Bydgoszcz Baechler, Christian, 53 Bromberg Bloody Sunday. See Bromberger Baltic Germans, 268 Blutsonntag Baltic Institute, 45, 208 Bromberger Blutsonntag, 4, 249 Bartkiewicz, Zygmunt, 118 Bromberger Volkszeitung, 134 Bauernverein, 72 Broszat, Martin, 205 Behrends, Hermann, 231 Brubaker, Rogers, 9, 26, 34, 63, 86, -

Germany's Policy Vis-À-Vis German Minority in Romania

T.C. TURKISH- GERMAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES EUROPE AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT GERMANY’S POLICY VIS-À-VIS GERMAN MINORITY IN ROMANIA MASTER’S THESIS Yunus MAZI ADVISOR Assoc. Prof. Dr. Enes BAYRAKLI İSTANBUL, January 2021 T.C. TURKISH- GERMAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES EUROPE AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT GERMANY’S POLICY VIS-À-VIS GERMAN MINORITY IN ROMANIA MASTER’S THESIS Yunus MAZI 188101023 ADVISOR Assoc. Prof. Dr. Enes BAYRAKLI İSTANBUL, January 2021 I hereby declare that this thesis is an original work. I also declare that I have acted in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct at all stages of the work including preparation, data collection and analysis. I have cited and referenced all the information that is not original to this work. Name - Surname Yunus MAZI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Enes Bayraklı. Besides my master's thesis, he has taught me how to work academically for the past two years. I would also like to thank Dr. Hüseyin Alptekin and Dr. Osman Nuri Özalp for their constructive criticism about my master's thesis. Furthermore, I would like to thank Kazım Keskin, Zeliha Eliaçık, Oğuz Güngörmez, Hacı Mehmet Boyraz, Léonard Faytre and Aslıhan Alkanat. Besides the academic input I learned from them, I also built a special friendly relationship with them. A special thanks goes to Burak Özdemir. He supported me with a lot of patience in the crucial last phase of my research to complete the thesis. In addition, I would also like to thank my other friends who have always motivated me to successfully complete my thesis. -

Nazi Visual Anti-Semitic Rhetoric

It’s Them or Us: Killing the Jews in Nazi Propaganda1 Randall Bytwerk Calvin College Why did the Nazis talk about killing the Jews and how did they present the idea to the German public? “Revenge. Go where you wanted me, you evil spirit.” (1933) Between 1919 and 1945, the core Nazi anti-Semitic argument was that Jews threatened the existence of Germany and the Germans, using nefarious and often violent means to reach their ultimate goal of world domination. Germans, on the other hand, were reacting in self-defense and resorted to violence only when driven to it by necessity. This essay considers a subset of Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda: images depicting either violence by Jews against Germans or violence by Germans 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Texas A & M University Conference on Symbolic Violence, March 2012. Nazi Symbolic Violence 2 against Jews.2 Although Nazi verbal rhetoric against Jews increased in vehemence over the years (particularly after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941), violent visual rhetoric declined both in frequency and vividness. The more murderous the Nazis became in practice, the less propaganda depicted violence by or against Jews. I divide the essay into three sections: the period before the Nazi takeover in 1933, from 1933 to the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, and from that invasion to the end of the war. I will take examples from a wide range of sources over the period, including posters, official Nazi party publications like Der Angriff in Berlin, the Nazi Party’s weekly illustrated magazine (the Illustrierter Beobachter), daily newspapers, two weekly humor publications, the prestige weekly Das Reich, several contemporary films, and Julius Streicher’s weekly anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer.3 Prelude to Power: 1923-1933 Before Hitler took power in 1933, the Nazis presented everyone in Germany as victims of Jewish power. -

Domesticating the German East: Nazi Propaganda and Women's Roles in the “Germanization” of the Warthegau During World Wa

DOMESTICATING THE GERMAN EAST: NAZI PROPAGANDA AND WOMEN’S ROLES IN THE “GERMANIZATION” OF THE WARTHEGAU DURING WORLD WAR II Madeline James A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the History Department in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Konrad Jarausch Karen Auerbach Karen Hagemann © 2020 Madeline James ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Madeline James: Domesticating the German East: Nazi Propaganda And Women’s Roles in the “Germanization” of the Warthegau during World War II (Under the direction of Konrad Jarausch and Karen Auerbach) This thesis utilizes Nazi women’s propaganda to explore the relationship between Nazi gender and racial ideology, particularly in relation to the Nazi Germanization program in the Warthegau during World War II. At the heart of this study is an examination of a paradox inherent in Nazi gender ideology, which simultaneously limited and expanded “Aryan” German women’s roles in the greater German community. Far from being “returned to the home” by the Nazis in 1933, German women experienced an expanded sphere of influence both within and beyond the borders of the Reich due to their social and cultural roles as “mothers of the nation.” As “bearers of German culture,” German women came to occupy a significant role in Nazi plans to create a new “German homeland” in Eastern Europe. This female role of “domesticating” the East, opposite the perceived “male” tasks of occupation, expulsion, and resettlement, entailed cultivating and reinforcing Germanness in the Volksdeutsche (ethnic German) communities, molding them into “future masters of the German East.” This thesis therefore also examines the ways in which Reich German women utilized the notion of a distinctly female cultural sphere to stake a claim in the Germanizing mission. -

Zwischen Propaganda Und Unterhaltung

16 Uhr Programm • Tamara Ehs: Politik und Recht der Entnazifizierung: Staatskünstler/innen Zwischen Propaganda SYMPOSIUM zwischen Amnesie und Amnestie und Unterhaltung SAMSTAG, 22. NOVEMBER 2014 • Diskussion Moderation Ines Steiner Zwischen Propaganda 12.30 Uhr 17.15 Uhr Symposium, 22. und 23. November 2014 • Begrüßung und Einführung • Frank Stern: Einführung zu AUFRUHR IN DAMASKUS und »Reichspogrom: METRO Kinokulturhaus, Johannesgasse 4 und Unterhaltung • Armin Loacker: Zur Biografie Gustav Ucickys Der Schauspieler Joachim Gottschalk«. • Frank Stern: Goebbels über Ucickys »ergreifende Kunstwerke« • Filmvorführung AUFRUHR IN DAMASKUS, D 1938, 84 Min. Der Regisseur Gustav Ucicky Alle Vorträge bei freiem Eintritt. 13 Uhr • Diskussion und Publikumsgespräch Für Symposiumsteilnehmer auch freier Entritt bei den begeleitenden • Thomas Koebner: Unpolitische Filme? 19.30 Uhr Filmprogrammen. Der Film HEIMKEHR kann nur im Doppelprogramm Gustav Ucickys FLÖTENKONZERT VON SANSSOUCI (D 1930), mit VERBOTENE FILME besucht werden. • Klaus Davidowicz: »So spricht das Volk nicht« MENSCH OHNE NAMEN (D 1932) und DER POSTMEISTER (D 1940) – MORGENROT zwischen Nationalismus und Militarismus mit einem kurzen Seitenblick auf die Filme von Willi Forst in den dreißiger Jahren Um Anmeldung unter [email protected] oder 01/216 13 00 • Filmvorführung MORGENROT, D 1933, 81 Min. • Ines Steiner: Mir tut das Mutterkreuz so weh wird gebeten. • Diskussion und Publikumsgespräch Gustav Ucickys Frauenbilder • Diskussion Moderation Armin Loacker 16 Uhr Referentinnen und Referenten Retrospektive Gustav Ucicky • Felix Moeller: Ufa, Tobis, Wien-Film Goebbels und die Filmproduktionsfirmen im Dritten Reich Christoph Brecht Literatur- und Filmwissenschaft - Felix Moeller Historiker, Politik- und Kommunikati - 20. November 2014 bis 11. Jänner 2015 ler. Forschungsschwerpunkte: Europäische Moderne, er - onswissenschaftler. Zahlreiche Publikationen zur (Film-) 17 Uhr zähltheoretische Aspekte von Literatur und Film, Kultur - Geschichte, darunter »Der Filmminister – Goebbels und semiotik, Medienkomparatistik. -

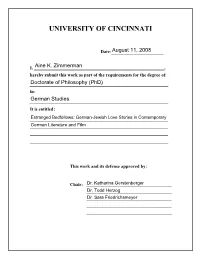

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Estranged Bedfellows: German-Jewish Love Stories in Contemporary German Literature and Film A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies at the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2008 by Aine K. Zimmerman Master of Arts, University of Washington, 2000 Bachelor of Arts, University of Cincinnati, 1997 Committee Chair: Professor Katharina Gerstenberger Abstract This dissertation is a survey and analysis of German-Jewish love stories, defined as romantic entanglements between Jewish and non-Jewish German characters, in German literature and film from the 1980s to the 21st century. Breaking a long-standing taboo on German-Jewish relationships since the Holocaust, there is a spate of such love stories from the late 1980s onward. These works bring together members of these estranged groups to spin out the consequences, and this project investigates them as case studies that imagine and comment on German-Jewish relations today. Post-Holocaust relations between Jews and non-Jewish Germans have often been described as a negative symbiosis. The works in Chapter One (Rubinsteins Versteigerung, “Aus Dresden ein Brief,” Eine Liebe aus nichts, and Abschied von Jerusalem) reinforce this description, as the German-Jewish couples are connected yet divided by the legacy of the Holocaust. -

A History of Al- Berta’S German-Speaking Communities

Biographical directory of clergy in Alberta’s German-speaking communities: From the 1880s to the present i Introduction This reference book deals with the lives and work of hundreds of pastors in eleven religious groups who have ministered to their German-speaking congregations in Alberta since the 1880s and have provided spiritual guidance and comfort. In their dedication the pioneering pastors often not only served, but led, bringing their faithful to Alberta and assisting them in establishing their families in the new homeland. They preached and taught, visited and counseled, performed the rites of passage, administered and di- rected, provided practical leadership in establishing the new congregations and played a pivotal role in developing their internal cohesion. No doubt, these pastors fulfilled an essential function in the settle- ment history of Albertans of German origin. Each of the eleven chapters commences with an outline of the early settlement history in Alberta of immi- grants of German origin before introducing the German-language pastors themselves. This Introduction attempts to examine and document in some detail the wider context in which the mem- bers of these religious groups and the pioneer pastors came to settle in Alberta (a more exhaustive exami- nation of the issues is available in several books by the compiler on the cultural history of the German- speaking communities in Alberta1). Three themes will be addressed: the reasons that brought these fami- lies to Alberta from countries in central and eastern Europe, the United States and Canadian provinces; the settlement history of immigrants of German origin in localities across the province and their religious affiliation; and the groups that facilitated their immigration to Canada.