A History of Al- Berta’S German-Speaking Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

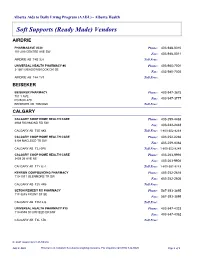

Soft Supports (Ready Made) Vendors

Alberta Aids to Daily Living Program (AADL) - Alberta Health Soft Supports (Ready Made) Vendors AIRDRIE PHARMASAVE #338 Phone: 403-948-0010 101-209 CENTRE AVE SW Fax: 403-948-0011 AIRDRIE AB T4B 3L8 Toll Free: UNIVERSAL HEALTH PHARMACY #6 Phone: 403-980-7001 3-1861 MEADOWBROOK DR SE Fax: 403-980-7002 AIRDRIE AB T4A 1V3 Toll Free: BEISEKER BEISEKER PHARMACY Phone: 403-947-3875 701 1 AVE Fax: 403-947-3777 PO BOX 470 BEISEKER AB T0M 0G0 Toll Free: CALGARY CALGARY COOP HOME HEALTH CARE Phone: 403-299-4488 4938 RICHMOND RD SW Fax: 403-242-2448 CALGARY AB T3E 6K4 Toll Free: 1-800-352-8249 CALGARY COOP HOME HEALTH CARE Phone: 403-252-2266 9309 MACLEOD TR SW Fax: 403-259-8384 CALGARY AB T2J 0P6 Toll Free: 1-800-352-8249 CALGARY COOP HOME HEALTH CARE Phone: 403-263-9994 3439 26 AVE NE Fax: 403-263-9904 CALGARY AB T1Y 6L4 Toll Free: 1-800-352-8249 KENRON COMPOUNDING PHARMACY Phone: 403-252-2616 110-1011 GLENMORE TR SW Fax: 403-252-2605 CALGARY AB T2V 4R6 Toll Free: SETON REMEDY RX PHARMACY Phone: 587-393-3895 117-3815 FRONT ST SE Fax: 587-393-3899 CALGARY AB T3M 2J6 Toll Free: UNIVERSAL HEALTH PHARMACY #10 Phone: 403-547-4323 113-8555 SCURFIELD DR NW Fax: 403-547-4362 CALGARY AB T3L 1Z6 Toll Free: © 2021 Government of Alberta July 9, 2021 This list is in constant flux due to ongoing revisions. For inquiries call (780) 422-5525 Page 1 of 6 Alberta Aids to Daily Living Program (AADL) - Alberta Health Soft Supports (Ready Made) Vendors CALGARY WELLWISE BY SHOPPERS DRUG MART Phone: 403-255-2288 25A-180 94 AVE SE Fax: 403-640-1255 CALGARY AB T2J 3G8 -

Larocque Investments Ltd June 21, 2019

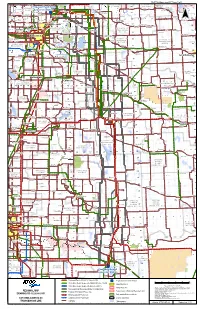

Unreserved Public Real Estate Auction Larocque Investments Ltd Will be sold to the highest bidder 1 Parcel of Real Estate – Potential Development Land – 48± Title Acres June 21, 2019 0.8 km of Hwy #2 Frontage – 1850± Sq Ft Home – Aldersyde, AB Edmonton Auction Site N Glenevis Stanger Morinville Lac Sainte Anne Mundare Entwistle 16 Lavoy Edmonton Beaverhill Lake AB/Hamlet of Aldersyde Cynthia Auction Location Nisku Ryley Viking Lodgepole Millet Breton Pigeon Lake Camrose Parcel 1 – PNE-6-20-28-W4 – 48± Title Acres – Potential Development Land Winfield Bawlf 2 Wetaskiwin 2 Killam Bluffton Ponoka ▸ 0.8 km of Hwy #2 frontage, located adjacent to Aldersyde Industrial Area Rimbey Heisler Bashaw Saunders Leedale Bentley Donalda Alliance Ferrier Mirror ▸ 1850± sq ft home, (4) bedroom, (3) bath, attached garage, power, Condor Alix Stettler N. Saskatchewan Strachan natural gas, water well, septic field system, livestock fenced Red Deer Ardley Castor Caroline Big Valley Bowden Innisfall Huxley Auction Property Scapa ▸ Currently Zoned A – Agricultural Potential Sundre Olds Maple Leaf Rd E Development Land Morrin Red Deer R. 2 Twining Current Hanna ▸ Taxes $2649.99. Industrial Land Water Valley Drumheller Beiseker East Coulee Crossfield 9 Red Deer R. 2A Banff Cochrane Rosebud Bow R. Calgary Standard 2 Exshaw Hussar Priddis 1 1 Aldersyde Bassano Princess Auction Property 2 Shouldice Brooks Longview 2A High River Milo Vulcan Directions to Property From Calgary, AB, go South on Hwy #2 for approx. 20 km to Exit 209, Hwy 7 West Okotoks, then South on Hwy 2A for 2.5 km to Aldersyde, then East on Maple Leaf Road for 0.8 km, property is on the South side. -

2018 Municipal Affairs Population List | Cities 1

2018 Municipal Affairs Population List | Cities 1 Alberta Municipal Affairs, Government of Alberta November 2018 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List ISBN 978-1-4601-4254-7 ISSN 2368-7320 Data for this publication are from the 2016 federal census of Canada, or from the 2018 municipal census conducted by municipalities. For more detailed data on the census conducted by Alberta municipalities, please contact the municipalities directly. © Government of Alberta 2018 The publication is released under the Open Government Licence. This publication and previous editions of the Municipal Affairs Population List are available in pdf and excel version at http://www.municipalaffairs.alberta.ca/municipal-population-list and https://open.alberta.ca/publications/2368-7320. Strategic Policy and Planning Branch Alberta Municipal Affairs 17th Floor, Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: (780) 427-2225 Fax: (780) 420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 780-420-1016 Toll-free in Alberta, first dial 310-0000. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2018 Municipal Census Participation List .................................................................................... 5 Municipal Population Summary ................................................................................................... 5 2018 Municipal Affairs Population List ....................................................................................... -

The French Canadians in Western Canada Their Churches

The French Canadians in Western Canada Their Churches Archives nationales du Québec Centre d'archives de Montréal Édifice Gilles-Hocquart 535, avenue Viger Est Montréal (Québec) H2L 2P3 Tél. : 514 873-1100, option 4 Téléc. : 514 873-2980 web: http://www.banq.qc.ca/a_propos_banq/informations_pratiques/centres _archives/index.html email: [email protected] This document was compiled by Jacques Gagne- [email protected] The Archives nationales du Québec in Montréal on Viger Avenue are the repository of a wonderful and unique collection of books of marriages, baptisms, deaths of French Canadian families who left the Province of Québec between 1840 and 1930 for destinations in Western Canada, especially in Alberta and Manitoba. Monsieur Daniel Olivier, former archivist at the Bibliothèque de la Ville de Montréal on Sherbrooke Street East, the latter no longer in operation, referred to for years as Salle Gagnon was responsible with the assistance of his associates for the acquisition of many of the books of marriages, baptisms, deaths, burials outlined in this research guide. www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?id_nbr=7384 Madame Estelle Brisson, former archivist at the Archives nationales du Québec on Viger Avenue East in Montréal with the assistance of her associates was also responsible for the acquisition of many of the books of marriages, baptisms, deaths, burials outlined in this research guide. dixie61.chez.com/brissoncanada1.html Alberta http://www.electricscotland.com/history/canada/alberta/vol1chap14.htm http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Separate_school -

St2 St9 St1 St3 St2

! SUPP2-Attachment 07 Page 1 of 8 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! .! ! ! ! ! ! SM O K Y L A K E C O U N T Y O F ! Redwater ! Busby Legal 9L960/9L961 57 ! 57! LAMONT 57 Elk Point 57 ! COUNTY ST . P A U L Proposed! Heathfield ! ! Lindbergh ! Lafond .! 56 STURGEON! ! COUNTY N O . 1 9 .! ! .! Alcomdale ! ! Andrew ! Riverview ! Converter Station ! . ! COUNTY ! .! . ! Whitford Mearns 942L/943L ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 56 ! 56 Bon Accord ! Sandy .! Willingdon ! 29 ! ! ! ! .! Wostok ST Beach ! 56 ! ! ! ! .!Star St. Michael ! ! Morinville ! ! ! Gibbons ! ! ! ! ! Brosseau ! ! ! Bruderheim ! . Sunrise ! ! .! .! ! ! Heinsburg ! ! Duvernay ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! 18 3 Beach .! Riviere Qui .! ! ! 4 2 Cardiff ! 7 6 5 55 L ! .! 55 9 8 ! ! 11 Barre 7 ! 12 55 .! 27 25 2423 22 ! 15 14 13 9 ! 21 55 19 17 16 ! Tulliby¯ Lake ! ! ! .! .! 9 ! ! ! Hairy Hill ! Carbondale !! Pine Sands / !! ! 44 ! ! L ! ! ! 2 Lamont Krakow ! Two Hills ST ! ! Namao 4 ! .Fort! ! ! .! 9 ! ! .! 37 ! ! . ! Josephburg ! Calahoo ST ! Musidora ! ! .! 54 ! ! ! 2 ! ST Saskatchewan! Chipman Morecambe Myrnam ! 54 54 Villeneuve ! 54 .! .! ! .! 45 ! .! ! ! ! ! ! ST ! ! I.D. Beauvallon Derwent ! ! ! ! ! ! ! STRATHCONA ! ! !! .! C O U N T Y O F ! 15 Hilliard ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! N O . 1 3 St. Albert! ! ST !! Spruce ! ! ! ! ! !! !! COUNTY ! TW O HI L L S 53 ! 45 Dewberry ! ! Mundare ST ! (ELK ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! . ! ! Clandonald ! ! N O . 2 1 53 ! Grove !53! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ISLAND) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ardrossan -

2019 Land Ownership

120°12'0"W 120°10'0"W 120°8'0"W 120°6'0"W 120°4'0"W 120°2'0"W 120°0'0"W 119°58'0"W 119°56'0"W 119°54'0"W 119°52'0"W 119°50'0"W 119°48'0"W 119°46'0"W 119°44'0"W 119°42'0"W 119°40'0"W 119°38'0"W 119°36'0"W 119°34'0"W 119°32'0"W 119°30'0"W 119°28'0"W 119°26'0"W 119°24'0"W 119°22'0"W 119°20'0"W 119°18'0"W 119°16'0"W 119°14'0"W 119°12'0"W 119°10'0"W 119°8'0"W 119°6'0"W 119°4'0"W 119°2'0"W 119°0'0"W 118°58'0"W 118°56'0"W 118°54'0"W 118°52'0"W 118°50'0"W 118°48'0"W 118°46'0"W 118°44'0"W 118°42'0"W 118°40'0"W 118°38'0"W 118°36'0"W 118°34'0"W 118°32'0"W 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 3 3 3 3 1 0 2 2 2 2 0 2 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 9 9 0 0 9 9 9 8 0 8 8 8 8 7 7 7 7 7 6 6 6 6 6 5 5 5 5 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 N 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 2 1 0 9 " 8 7 6 5 E E E E E E E E E 0 E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E D D D E E E E E ' D D D D D E E E E N D D D D E E E E D D D D E E D D D D 1 D D D D G G G G D D D D D 1 G G G G G D D D D D 1 G G G G D D D G G G G D D D D G G G G D D D R R R 1 G G G G " R R R R R G G G G R R R R G G G G G R R R R G G G G R R R R G G G G 4 R R R R G G R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R R 0 R R 2 ' E E ° E E E E 4 E E E D D D D D 6 D D D G D 2 G G G G G G R G R G R R 5 R ° R R R R R R R R R R R R R 6 5 M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M M 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W W 3 2 2 1 1 0 0 9 9 8 8 7 7 6 6 5 5 4 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 E E E E E E E E E E E E E E -

Published Local Histories

ALBERTA HISTORIES Published Local Histories assembled by the Friends of Geographical Names Society as part of a Local History Mapping Project (in 1995) May 1999 ALBERTA LOCAL HISTORIES Alphabetical Listing of Local Histories by Book Title 100 Years Between the Rivers: A History of Glenwood, includes: Acme, Ardlebank, Bancroft, Berkeley, Hartley & Standoff — May Archibald, Helen Bircham, Davis, Delft, Gobert, Greenacres, Kia Ora, Leavitt, and Brenda Ferris, e , published by: Lilydale, Lorne, Selkirk, Simcoe, Sterlingville, Glenwood Historical Society [1984] FGN#587, Acres and Empires: A History of the Municipal District of CPL-F, PAA-T Rocky View No. 44 — Tracey Read , published by: includes: Glenwood, Hartley, Hillspring, Lone Municipal District of Rocky View No. 44 [1989] Rock, Mountain View, Wood, FGN#394, CPL-T, PAA-T 49ers [The], Stories of the Early Settlers — Margaret V. includes: Airdrie, Balzac, Beiseker, Bottrell, Bragg Green , published by: Thomasville Community Club Creek, Chestermere Lake, Cochrane, Conrich, [1967] FGN#225, CPL-F, PAA-T Crossfield, Dalemead, Dalroy, Delacour, Glenbow, includes: Kinella, Kinnaird, Thomasville, Indus, Irricana, Kathyrn, Keoma, Langdon, Madden, 50 Golden Years— Bonnyville, Alta — Bonnyville Mitford, Sampsontown, Shepard, Tribune , published by: Bonnyville Tribune [1957] Across the Smoky — Winnie Moore & Fran Moore, ed. , FGN#102, CPL-F, PAA-T published by: Debolt & District Pioneer Museum includes: Bonnyville, Moose Lake, Onion Lake, Society [1978] FGN#10, CPL-T, PAA-T 60 Years: Hilda’s Heritage, -

The Relationship Between Religious and National Identity in the Case Of

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN RELIGIOUS AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN THE CASE OF TRANSYLVANIAN SAXONS 1933-1944 By Cristian Cercel Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Advisor: Prof. András Kovacs External Research Advisor: Dr. Stefan Sienerth (Institut für deutsche Kultur und Geschichte Südosteuropas, Munich) CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2007 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the IKGS (Institut für deutsche Kultur und Geschichte Südosteuropas) in Munich whose financial assistance enabled me to do the necessary research for this thesis. Georg Aescht, Marius Babias and Matthias Volkenandt deserve all my gratitude for their help in assuring me a fruitful and relaxed stay in Munich. I am also grateful to Peter Motzan for his encouragement and insightful suggestions regarding the history of the Transylvanian Saxons. The critical contribution of Dr. Stefan Sienerth has definitely improved this thesis. Its imperfections, hopefully not many, belong only to me. I am also thankful to Isabella Manassarian for finding the time to read and make useful and constructive observations on the text. CEU eTD Collection i Preface This thesis analyzes the radicalization undergone by the Transylvanian Saxon community between 1933 and 1940 from an identity studies perspective. My hypothesis is that the Nazification of the Saxon minority in Romania was accompanied by a relegation of the Lutheran religious affiliation from the status of a criterion of identity to that of an indicium. In order to prove the validity of the argument, I resorted to the analysis of a various number of sources, such as articles from the official periodical of the Lutheran Church, diaries and contemporary documents. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00830-4

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00830-4 - The German Minority in Interwar Poland Winson Chu Index More information Index Agrarian conservativism, 71 Beyer, Hans Joachim, 212 Alldeutscher Verband. See Pan-German Bielitz. See Bielsko League Bielitzer Kreis, 174 Allgemeiner Schulverein, 36 Bielsko, 25, 173, 175, 203 Alltagsgeschichte, 10 Bielsko Germans, 108, 110, 111 Ammende, Ewald, 136 Bierschenk, Theodor, 137, 216, 224 Anschluß question, 51, 52 Bjork, James, 17 Anti-Communism, 165 Blachetta-Madajczyk, Petra, 9, 130, 136 Anti-Germanism, 214, 244, 245 Black Palm Sunday, 213–217 Anti-Semitism, 38, 79, 151, 159, 166, 178, Blanke, Richard, 9, 65, 76, 90, 136, 162 212, 215, 244, 260 Boehm, Max Hildebert, 31, 39, 46, 54, 88, Association for Germandom Abroad. See 97, 99, 110, 205 Verein fur¨ das Deutschtum im Ausland Border Germans and Germans Abroad, 44 Auslandsdeutsche, 98, 206.SeealsoReich Brackmann, Albert, 45, 208 Germans; Reich Germans, former Brauer, Leo, 221 Auslands-Organisation der NSDAP, 180, Brest-Litovsk Treaty, 42 205 Breuler, Otto, 103 Austria, 34, 165, 173, 207 Breyer, Albert, 153, 155, 212 annexation of, 51 Breyer, Richard, 155, 216, 272, 274 Austrian Silesia. See Teschen Silesia Briand, Aristide, 50 Bromberg. See Bydgoszcz Baechler, Christian, 53 Bromberg Bloody Sunday. See Bromberger Baltic Germans, 268 Blutsonntag Baltic Institute, 45, 208 Bromberger Blutsonntag, 4, 249 Bartkiewicz, Zygmunt, 118 Bromberger Volkszeitung, 134 Bauernverein, 72 Broszat, Martin, 205 Behrends, Hermann, 231 Brubaker, Rogers, 9, 26, 34, 63, 86, -

German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Paper HEC No. 2004/1 The Expulsion of the ‘German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War Edited by STEFFEN PRAUSER and ARFON REES BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO (FI) All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author(s). © 2004 Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees and individual authors Published in Italy December 2004 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50016 San Domenico (FI) Italy www.iue.it Contents Introduction: Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees 1 Chapter 1: Piotr Pykel: The Expulsion of the Germans from Czechoslovakia 11 Chapter 2: Tomasz Kamusella: The Expulsion of the Population Categorized as ‘Germans' from the Post-1945 Poland 21 Chapter 3: Balázs Apor: The Expulsion of the German Speaking Population from Hungary 33 Chapter 4: Stanislav Sretenovic and Steffen Prauser: The “Expulsion” of the German Speaking Minority from Yugoslavia 47 Chapter 5: Markus Wien: The Germans in Romania – the Ambiguous Fate of a Minority 59 Chapter 6: Tillmann Tegeler: The Expulsion of the German Speakers from the Baltic Countries 71 Chapter 7: Luigi Cajani: School History Textbooks and Forced Population Displacements in Europe after the Second World War 81 Bibliography 91 EUI WP HEC 2004/1 Notes on the Contributors BALÁZS APOR, STEFFEN PRAUSER, PIOTR PYKEL, STANISLAV SRETENOVIC and MARKUS WIEN are researchers in the Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute, Florence. TILLMANN TEGELER is a postgraduate at Osteuropa-Institut Munich, Germany. Dr TOMASZ KAMUSELLA, is a lecturer in modern European history at Opole University, Opole, Poland. -

Germany's Policy Vis-À-Vis German Minority in Romania

T.C. TURKISH- GERMAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES EUROPE AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT GERMANY’S POLICY VIS-À-VIS GERMAN MINORITY IN ROMANIA MASTER’S THESIS Yunus MAZI ADVISOR Assoc. Prof. Dr. Enes BAYRAKLI İSTANBUL, January 2021 T.C. TURKISH- GERMAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES EUROPE AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT GERMANY’S POLICY VIS-À-VIS GERMAN MINORITY IN ROMANIA MASTER’S THESIS Yunus MAZI 188101023 ADVISOR Assoc. Prof. Dr. Enes BAYRAKLI İSTANBUL, January 2021 I hereby declare that this thesis is an original work. I also declare that I have acted in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct at all stages of the work including preparation, data collection and analysis. I have cited and referenced all the information that is not original to this work. Name - Surname Yunus MAZI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Enes Bayraklı. Besides my master's thesis, he has taught me how to work academically for the past two years. I would also like to thank Dr. Hüseyin Alptekin and Dr. Osman Nuri Özalp for their constructive criticism about my master's thesis. Furthermore, I would like to thank Kazım Keskin, Zeliha Eliaçık, Oğuz Güngörmez, Hacı Mehmet Boyraz, Léonard Faytre and Aslıhan Alkanat. Besides the academic input I learned from them, I also built a special friendly relationship with them. A special thanks goes to Burak Özdemir. He supported me with a lot of patience in the crucial last phase of my research to complete the thesis. In addition, I would also like to thank my other friends who have always motivated me to successfully complete my thesis. -

Domesticating the German East: Nazi Propaganda and Women's Roles in the “Germanization” of the Warthegau During World Wa

DOMESTICATING THE GERMAN EAST: NAZI PROPAGANDA AND WOMEN’S ROLES IN THE “GERMANIZATION” OF THE WARTHEGAU DURING WORLD WAR II Madeline James A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the History Department in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Konrad Jarausch Karen Auerbach Karen Hagemann © 2020 Madeline James ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Madeline James: Domesticating the German East: Nazi Propaganda And Women’s Roles in the “Germanization” of the Warthegau during World War II (Under the direction of Konrad Jarausch and Karen Auerbach) This thesis utilizes Nazi women’s propaganda to explore the relationship between Nazi gender and racial ideology, particularly in relation to the Nazi Germanization program in the Warthegau during World War II. At the heart of this study is an examination of a paradox inherent in Nazi gender ideology, which simultaneously limited and expanded “Aryan” German women’s roles in the greater German community. Far from being “returned to the home” by the Nazis in 1933, German women experienced an expanded sphere of influence both within and beyond the borders of the Reich due to their social and cultural roles as “mothers of the nation.” As “bearers of German culture,” German women came to occupy a significant role in Nazi plans to create a new “German homeland” in Eastern Europe. This female role of “domesticating” the East, opposite the perceived “male” tasks of occupation, expulsion, and resettlement, entailed cultivating and reinforcing Germanness in the Volksdeutsche (ethnic German) communities, molding them into “future masters of the German East.” This thesis therefore also examines the ways in which Reich German women utilized the notion of a distinctly female cultural sphere to stake a claim in the Germanizing mission.