Block Statue تماثيل الكتلة

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

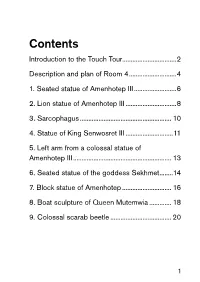

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour................................2 Description and plan of Room 4 ............................4 1. Seated statue of Amenhotep III .........................6 2. Lion statue of Amenhotep III ..............................8 3. Sarcophagus ...................................................... 10 4. Statue of King Senwosret III ............................11 5. Left arm from a colossal statue of Amenhotep III .......................................................... 13 6. Seated statue of the goddess Sekhmet ........14 7. Block statue of Amenhotep ............................. 16 8. Boat sculpture of Queen Mutemwia ............. 18 9. Colossal scarab beetle .................................... 20 1 Introduction to the Touch Tour This tour of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery is a specially designed Touch Tour for visitors with sight difficulties. This guide gives you information about nine highlight objects in Room 4 that you are able to explore by touch. The Touch Tour is also available to download as an audio guide from the Museum’s website: britishmuseum.org/egyptiantouchtour If you require assistance, please ask the staff on the Information Desk in the Great Court to accompany you to the start of the tour. The sculptures are arranged broadly chronologically, and if you follow the tour sequentially, you will work your way gradually from one end of the gallery to the other moving through time. Each sculpture on your tour has a Touch Tour symbol beside it and a number. 2 Some of the sculptures are very large so it may be possible only to feel part of them and/or you may have to move around the sculpture to feel more of it. If you have any questions or problems, do not hesitate to ask a member of staff. -

A Social and Religious Analysis of New Kingdom Votive Stelae from Asyut

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Display and Devotion: A Social and Religious Analysis of New Kingdom Votive Stelae from Asyut A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures by Eric Ryan Wells 2014 © Copyright by Eric Ryan Wells ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Display and Devotion: A Social and Religious Analysis of New Kingdom Votive Stelae from Asyut by Eric Ryan Wells Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Jacco Dieleman, Chair This dissertation is a case study and analysis of provincial religious decorum at New Kingdom Asyut. Decorum was a social force that restricted and defined the ways in which individuals could engage in material displays of identity and religious practice. Four-hundred and ninety-four votive stelae were examined in an attempt to identify trends and patters on self- display and religious practice. Each iconographic and textual element depicted on the stelae was treated as a variable which was entered into a database and statistically analyzed to search for trends of self-display. The analysis of the stelae revealed the presence of multiple social groups at Asyut. By examining the forms of capital displayed, it was possible to identify these social groups and reconstruct the social hierarchy of the site. This analysis demonstrated how the religious system was largely appropriated by elite men as a stage to engage in individual competitive displays of identity and capital as a means of reinforcing their profession and position in society and the II patronage structure. -

Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part XXXVII: Human Stone Statues Industry (Third Intermediate and Late Periods)

International Journal of Recent Engineering Science (IJRES), ISSN: 2349-7157, volume31 January 2017 Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part XXXVII: Human Stone Statues Industry (Third Intermediate and Late Periods) Galal Ali Hassaan Emeritus Professor, Department of Mechanical Design & Production, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt ABSTRACT: The objective of this paper is to Udjahorresnet (519-510 BC) [4] investigate the development of mechanical Wikipedia (2016) wrote two articles about engineering in ancient Egypt through the Pharaohs Shabata (721-707 BC) and Taharqa (690- production of human stone statues during the Third 664 BC) of the 25th Dynasty. They presented a Intermediate and Late Periods. This study covers stone head and a broken statue for Pharaoh the design and production of stone statues Shabaka in display in the Louvre Museum at Paris. from the 21st to the 31st Dynasties showing the For Pharaoh Taharqa, they presented a granite type and characteristics of each statue. The sphinx from Kawa in Sudan, a kneeling statue offering jars to Falcon-God Hemen and a Shabti for decoration, inscriptions and beauty aspects of him [5,6]. Hassaan (2016,2017) investigated the each statue were highlighted. evolution of mechanical engineering in ancient Egypt through studying the industry of the human Keywords –Mechanical engineering history, stone statues in periods extending from the Predynastic down to the 20th Dynasty. He presents stone statues, Third Intermediate Period, Late too many examples of human stone statues from Period. each period focusing on the mechanical characteristics of each statue [7-10]. I. INTRODUCTION Ancient Egyptians built a great stone industry for II. -

In the Tomb of Nefertari: Conservation of the Wall Paintings

IN THE TOMB OF NEFERTAR1 IN THE TOMB OF NEFERTARI OF CONSERVATION THE WALL PAINTINGS THE J.PAUL GETTY MUSEUM AND THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTTE 1992 © 1992 The j. Paul Getty Trust Photo Credits: Guillermo Aldana, figs. I, 2, 4, 8-17, 30, 34-36, 38, cover, 401 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 900 endsheets, title page, copyright page, table of contents; Archives of Late Egyp Santa Monica, California 90401 -1455 tian Art, Robert S. Bianchi, New York, figs. 18, 20, 22-27, 31-33,37; Cleveland Museum of Art, fig. 29; Image processing by Earthsat, fig. 7; Metropolitan Kurt Hauser, Designer Museum of Art, New York, figs. 6, 19, 28; Museo Egizio, Turin, figs. 5, 21 (Lovera Elizabeth Burke Kahn, Production Coordinator Giacomo, photographer), half-title page. Eileen Delson, Production Artist Beverly Lazor-Bahr, Illustrator Cover: Queen Nefertari. Chamber C, south wall (detail), before treatment was completed. Endsheets: Ceiling pattern, yellow five-pointed stars on dark blue Typography by Wilsted & Taylor, Oakland, California ground. Half-title page: Stereo view of tomb entrance taken by Don Michele Printing by Westland Graphics, Burbank, California Piccio/Francesco Ballerini, circa 1904. Title page: View of Chamber K, looking Library of Congress Catalogmg-in-Publication Data north. Copyright page: Chamber C, south wall, after final treatment-Table of In the tomb of Nefertari : conservation of the wall paintings, Contents page: Chamber C, south wall (detail), after final treatment. Tomb of p. cm. Nefertari, Western Thebes, Egypt. "Published on the occasion of an exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Published on the occasion of an exhibition atthej. -

Amenhotep Son of Hapu: Self-Presentation Through Statues and Their Texts in Pursuit of Semi-Divine Intermediary Status

AMENHOTEP SON OF HAPU: SELF-PRESENTATION THROUGH STATUES AND THEIR TEXTS IN PURSUIT OF SEMI-DIVINE INTERMEDIARY STATUS By ELEANOR BETH SIMMANCE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Master of Research (Egyptology) Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham April 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The name of Amenhotep son of Hapu is well-known to scholars. He was similarly distinguished in ancient times as one who reached extraordinary heights during life and whose memory was preserved for centuries after death. This thesis engages with the premise that an individual constructed monuments for commemoration and memorialisation, and thus that the individual was governed by this motive during their creation. Two statues of Amenhotep in particular are believed to have served as mediators between human and god, and by exploring the ways in which he presented himself on the nine contemporary statues which are currently known (all but one originating at Karnak) it is argued that he deliberately portrayed himself as a suitable intermediary, encouraging this form of remembrance. -

Block Statue in the Cairo Museum JE 37185 from Karnak Cachette, Excavation Number K.382 Eman Abu-Zaid*

Studies on the Arab World monuments 18 Block Statue in the Cairo Museum JE 37185 from Karnak Cachette, Excavation Number K.382 Eman Abu-Zaid* Abstract: In the Ismailia Museum1 is a block statue No. JE 371852 of a certain @r, who was the son of Jy-m-ḥtp and Kr-hb. This statue has not been published previously3, It was found by Legrain in the Karnak Cache4 on 4/6/1904. Now, this object is stored in the magazine of Ismailia Museum in a good state of preservation, except for some shattering in the palm of the left hand with his elbow. The wide back pillar and the front of the statue keeping complete inscriptions, except the last line on the front. the present study will discuss the statue, the scenes and the inscriptions that carved on its surface. Key words: Karnak Cache, Block statue, Ismailia Museum. ألقى البحث بالنيابة أ.نيرة أحمد جﻻل الدين * Associate Professor at the Faculty of Archaeology, Egyptology Dept., South Valley University, Qena. Email: [email protected] 1 It was transferred to Ismailia Museum from Cairo museum in 2004. 2 I would like to express my appreciation to the Director of the Ismailia Museum for permission to publish the statue herein. 3 This statue has not been published previously, though it was referred to by De Meulenaere,“La prosopographie thébaine de l’époque ptolémaïque à la lumière des sources hiéroglyphiques”, in S.P. Vleeming (ed.), Hundred-gates Thebes : Acts of a colloquium on Thebes and the Theban area in the Graeco-roman period, 9-11 september 1992. -

A Shabti of “Tjehebu the Great:” Tjainhebu (7Ay-N-Hbw) and Related Names from Middle Kingdom to Late Period

A Shabti of “Tjehebu the Great:” Tjainhebu (7Ay-n-Hbw) and Related Names from Middle Kingdom to Late Period Lloyd D. Graham Section 1 of this paper describes a pottery shabti of the Third Intermediate Period and recounts the early stages of the project to understand the name of its owner. Sections 2- 7 describe the outcome of the analysis. This covers both the name itself (its variants, orthographies and possible meanings) and a survey of those individuals who bore it in ancient Egypt, ordered by time-period. 7-Hbw-aA seems to be a variant of the name 7A- n-Hb aA and to denote “Tjainhebu the Great;” 7A(y)-n-Hb.w may originally have meant something like “the man of the festivals.” The earliest known Tjainhebu dates to the Middle Kingdom and was probably called “the Great” to reflect his physical size. Precedents are discussed for the unusual orthography of the name on the shabti and its cognates. Some later names of similar form employ different types of h and therefore differ in meaning; for example, the name of Tjainehebu, Overseer of the King’s Ships in the 26th Dynasty, may have meant “Descendant of the ibis.” In the Late Period, both male and female forms of the name are known and seem to relate strongly to Lower Egypt: for men, to Memphis; for women, to Behbeit el-Hagar and Khemmis of the Delta. Faces can be put to two of the men, leading to a discussion of the verisimilitude of ancient Egyptian likenesses. Overall, the article presents an unpublished shabti with six known parallels that imply at least three moulds. -

OLA265 Jurman

University of Birmingham Impressions of what is lost Jurman, Claus License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Jurman, C 2018, Impressions of what is lost: A study on four Late Period seal impressions in Birmingham and London. in C Jurman, B Bader & D Aston (eds), A true scribe of Abydos: Essays on First Millennium Egypt in Honour of Anthony Leahy. vol. 265, Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, vol. 265, Peeters Publishers, Leuven, Paris, Bristol, CT, pp. 239-272. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility 15/06/2018 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. -

In Situ Fall 2019

In Situ Fall 2019 News and Events of the Harvard Standing Committee on Archaeology Ayn Sokhna camp on the Red Sea coast; see page 19 In this issue: Projects focusing on China, Egypt, Fenno-Scandinavia, Israel, Peru, Spain, Sudan, and USAFall 2019 1 In Situ Note from the Chair News and Events of the Harvard Standing Committee on Archaeology Fall Semester 2019 fter a publication hiatus in 2018–2019, this Anew issue of In Situ provides an informal news- Contents letter describing some of the diverse activities and achievements by archaeologists across the Harvard community and beyond. The following pages briefly Note from the Chair 2 summarize eleven different projects, some taking Archaeological heritage in Pre-Hispanic place right here on the Harvard campus, others as far Cajamarca; “El pasado importa” away as China. We are particularly happy to high- Solsire Cusicanqui 3 light graduate student work, and I encourage you to explore the wide range of technologies they are The Tao River Archaeology Project—2019 applying to their research questions. 6 SU Xin In addition, we list the many events related to the Modeling Royal Nubian Landscapes: Bringing the Standing Committee on Archaeology’s mission on “Drone Revolution” to Northern Sudan campus this past semester, even as we look ahead to Katherine Rose 7 a busy and no doubt productive spring 2020. For fundamental support, both logistical and Sámi Collections at the Smithsonian Institution moral, we thank the Dean of Social Sciences, Prof. 11 Matthew Magnani Lawrence Bobo, and the Dean of Humanities, Prof. Together at Last: Ankh-khonsu Regains his Robin Kelsey. -

The Life of Meresamun Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu The life of MeresaMun oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu The life of MeresaMun a temple singer in ancient egypt edited by eMily TeeTer and JaneT h. Johnson The orienTal insTiTuTe MuseuM publicaTions • nuMber 29 The orienTal insTiTuTe of The universiTy of chicago oi.uchicago.edu The life of meresamun Library of Congress Control Number: 2008942017 ISBN-10: 1-885923-60-0 ISBN-13: 978-1-885923-60-8 © 2009 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2009. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago This volume has been published in conjunction with the exhibition The Life of Meresamun: A Temple Singer in Ancient Egypt, presented at The Oriental Institute Museum, February 10–December 6, 2009. Oriental Institute Museum Publications No. 29 The Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban would like to thank Sabahat Adil and Kaye Oberhausen for their help in the production of this volume. Published by The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 1155 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 USA oi.uchicago.edu Meresamun’s name appears in hieroglyphs on the title page. This publication has been made possible in part by the generous support of Philips Healthcare. Printed by M&G Graphics, Chicago, Illinois. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Service — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984 ∞ 4 oi.uchicago.edu a Temple singer in ancienT egypT TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword. Gil J. Stein ................................................................................................................................... 7 Preface. Geoff Emberling .............................................................................................................................. -

G:\Lists Periodicals\Periodical Lists B\British Museum Magazine.Wpd

British Museum Magazine Past and present members of the staff of the Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Stelae, Reliefs and Paintings, especially R. L. B. Moss and E. W. Burney, have taken part in the analysis of this periodical and the preparation of this list at the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford This pdf version (situation on 23 November 2009): Jaromir Malek (Editor), Diana Magee, Elizabeth Fleming and Alison Hobby (Assistants to the Editor) Jones, M. in British Museum Magazine 1 (1990), fig. on 28 [upper] Thebes. Dra Abû-Naga. Finds. i2.612A Seated statue of Queen Tetisheri, in London, British Museum EA 22558. Jones, M. in British Museum Magazine 1 (1990), fig. on 28 [lower left] Sidmant. Tomb of Meryre-hashetef. iv.115A Ebony statuette of deceased as youth, in British Museum EA 55722. Jones, M. in British Museum Magazine 1 (1990), fig. on 28 [lower right] Omit. Wooden statue-base with a forged statue, Middle Kingdom, in British Museum EA 55584. see British Museum Magazine 1 (1990), 47 8 Relief, lower part of King, temp. Amenophis IV, in British Museum EA 71571. see British Museum Magazine 3 (1990), 27 Gîza. Tomb LG 98. Dyn. IV-V. iii2.276A Red granite sarcophagus, in British Museum. British Museum Magazine 3 (1990), fig. on 27 [left] 801-447-330 Male head, black steatite, probably 2nd half Dyn. XII in British Museum EA 71645. Reeve, J. in British Museum Magazine 4 (1990), fig. on 13 [left lower] Gebel Barkal. Temples B.1100 and 1200. vii.212A Granite lion of Amenophis III, in British Museum EA 1.