Finding Nefertiti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 King's Chamber

Revelation Research Foundation, Inc. Hamburg, NJ 07419, USA © 2015 Contents Author’s and Editor’s Notes . v Photo/Illustration Acknowledgments . vi Pyramid Chart . vii Chapter 1: God’s Stone Witness in Egypt . 1 Chapter 2: Chart of Interior Chambers and Passage System . 13 Chapter 3: The Entrance . 19 Chapter 4: Well Shaft and Grotto . 21 Chapter 5: Grand Gallery and Antechamber . 29 Chapter 6: King’s Chamber . 39 Chapter 7: Construction Chambers . 47 Chapter 8: Horizontal Passage and Queen’s Chamber . 53 Chapter 9: The Top Stone . 59 Chapter 10: Chronology of the Passage System . 63 Chapter 11: Three Pyramids of the Gizeh Plateau . 71 Chapter 12: The Sphinx . 75 Chapter 13: Ararat . 77 Chapter 14: Great Pyramid and Mount Ararat . 81 Song of Praise . 87 Appendix A: The Garden Tomb . 89 Appendix B: Queen Hatshepsut and Her Mortuary Temple . 93 Appendix C: The Solar Boat . 97 Appendix D: Location of Noah’s Ark . 101 Appendix E: Great Seal of the United States . 103 Appendix F: Pharaoh of the Exodus . 109 iii Appendix G: Twelfth Dynasty of Manetho . 115 Appendix H: The Abydos Tablets . 119 Appendix I: Planes of Perfection . 123 Appendix J: Granite Fragments in Great Pyramid . 125 Appendix K: Excavation at Top of Well Shaft . 127 Addendum: Origin of the Pyramid . 129 iv AUTHOR’S NOTE When properly understood, the title and subject matter of this work, A Rock of the Ages: The Great Pyramid, do no injustice to the theme of that grand old hymn “Rock of Ages,” for the Great Pyramid of Egypt clearly accentuates the centricity of Christ in abolishing death and bringing to light the two salvations—life and immortality (2 Tim. -

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

Hotep 0059A May-Jun21.Pdf

The newsletter of The Southampton HOTEP Issue 59: May-June 2021 Ancient Egypt Society Review of May meeting Other well-known objects found at the temple site were the large and small May’s lecture was given by Liam copper statues form the sixth dynasty. The McNamara on ‘Exploring the Dynastic larger one is inscribed for Pepi I but the Town and Temple at Hierakonpolis.’ smaller, which was found inside the torso of Liam is the Lisa and Bernard Selz Curator for the larger, is not. It has generally been Ancient Egypt and Sudan at the Ashmolean thought to be the son of Pepi I, Merenre. Museum and Director of the Griffith Institute However, Liam said that the pair is now at the University of Oxford. He is also the thought to be related to the Pepi I’s Heb Assistant Director of the Ashmolean’s Sed, with the smaller one representing the Expedition to Hierakonpolis and Elkab, and reborn king. his experience with this expedition was the focus of his talk. Liam began by showing a map of the site which is to the north of Edfu and on the west bank of the Nile. The ancient Egyptian name for the site was Nekhen and on the opposite bank is Elkab. The first major excavations on the town site were undertaken by Frederick Green and James Quibell, between 1897-9. It was during this excavation that the Main Deposit was discovered. This assemblage of ritual and votive objects, which included the Narmer palette, was referred to by Green as ‘Holy Rubbish’. -

ROYAL STATUES Including Sphinxes

ROYAL STATUES Including sphinxes EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD Dynasties I-II Including later commemorative statues Ninutjer 800-150-900 Statuette of Ninuter seated wearing heb-sed cloak, calcite(?), formerly in G. Michaelidis colln., then in J. L. Boele van Hensbroek colln. in 1962. Simpson, W. K. in JEA 42 (1956), 45-9 figs. 1, 2 pl. iv. Send 800-160-900 Statuette of Send kneeling with vases, bronze, probably made during Dyn. XXVI, formerly in G. Posno colln. and in Paris, Hôtel Drouot, in 1883, now in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 8433. Abubakr, Abd el Monem J. Untersuchungen über die ägyptischen Kronen (1937), 27 Taf. 7; Roeder, Äg. Bronzefiguren 292 [355, e] Abb. 373 Taf. 44 [f]; Wildung, Die Rolle ägyptischer Könige im Bewußtsein ihrer Nachwelt i, 51 [Dok. xiii. 60] Abb. iv [1]. Name, Gauthier, Livre des Rois i, 22 [vi]. See Antiquités égyptiennes ... Collection de M. Gustave Posno (1874), No. 53; Hôtel Drouot Sale Cat. May 22-6, 1883, No. 53; Stern in Zeitschrift für die gebildete Welt 3 (1883), 287; Ausf. Verz. 303; von Bissing in 2 Mitteilungen des Kaiserlich Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung xxxviii (1913), 259 n. 2 (suggests from Memphis). Not identified by texts 800-195-000 Head of royal statue, perhaps early Dyn. I, in London, Petrie Museum, 15989. Petrie in Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland xxxvi (1906), 200 pl. xix; id. Arts and Crafts 31 figs. 19, 20; id. The Revolutions of Civilisation 15 fig. 7; id. in Anc. Eg. (1915), 168 view 4; id. in Hammerton, J. A. -

II. 9 RELATIVE CHRONOLOGY of DYN. 21 Karl Jansen-Winkeln At

II. 9 RELATIVE CHRONOLOGY OF DYN. 21 Karl Jansen-Winkeln At the beginning of Dyn. 21 Egypt was split in two, with two centres of power, each ruled individually. UE, whose northern frontier was located in the region of Herakleopolis, was governed by a military com- mander who, at the same time was HPA of Thebes.1 In texts and depictions some of these UE regents (Herihor, Pinudjem I and Menkheperre) assume in varying degrees attributes which are reserved for a king. Kings reigned in LE, but at least two of them (Psusennes and Amenemope) occasionally bear the title of “HPA”. Contemporaneous documents of which only a small number survived do not give any direct indication as to the reason for this partition of Egypt.2 The only large group of finds are the graves of the kings in Tanis and the col- lective interments in the Theban necropolis (including replacements and re-interments of older mummies). Among these Theban funeral sites various dated objects can be found, but unfortunately most dates are anonymous and not ascribed to any explicit regent. Of this twofold line of regents, Manetho lists only the kings of LE, namely (1) Smendes, (2) Psusennes [I], (3) Nepherkheres, (4) Amenophthis, (5) Osochor, (6) Psinaches, (7) Psusennes [II]. Contemporary documents contain ample reference of the kings Psusennes (P#-sb#-¢'j-m-nwt; only in LE), Amenemope ( Jmn-m-Jpt) and Siamun (Z#-Jmn) (both in LE and UE). The first two kings can be straightforwardly identified as Manetho’s Psusennes (I) and Amenophthis. A king named Smendes (Ns-b#-nb-ddt) is attested by only a few, undated inscriptions, but the history of Wenamun shows clearly that he was a contemporary of Herihor and thus the first king of Dyn. -

House of Eternity: Tomb of Nefertari

- - - OUSE OF ETERNITY The Tomb of Nefertari John K. McDonald The Getty Conservation Institute and the J. Paul Getty Museum Los Angeles Cover/title page: Detail a/Queen Nefertari 0/'1 the north wall of Chamber G. All photographs are by Guillermo Aldana unless credited otherwise. The Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to further the appreciation and preservation of the world's cultural heritage for the enrichment and use of present and future generations. This is the first volume in the Conservation and Cultural Heritage series, which aims to provide in a popular format information about selected culturally significant sites throughout the world. © 1996 The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in Singapore Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McDonald. John K. House of eternity: the tomb of Nefertari I John K. McDonald. p. cm. ISBN 0-89236-415-7 1. Nefertari. Queen. consort of Rameses II. King of Egypt-Tomb. 2. Mural painting and decoration. Egyptian. 3. Tombs-Egypt. 4. Valley of the Queens (Egypt) I. Title. DT73· v34M35 1996 932-dc20 96-24123 C1P Contents Foreword 5 Introduction Dynasties of Ancient Egypt II Nefertari: Radiant Queen A Letter from Nefertari The Queen's Titles and Epithets 19 The Valley of the Queens Ernesto Schiaparelli 25 Conveyance to Eternal Life: The Royal Tombs of Egypt Tomb Paints and Materials 33 The Tomb Builders' Village 37 After Nefertari's Burial 41 Resurrection and Recurrent Risks 47 The King of the Dead and His Divine Family Divine Guidance 55 Among the Immortals: A Walk through the "House of Eternity" The Texts in the Tomb III Conclusion 116 Acknowledgments II HOUSE OF ETER ITY an honored and < > beloved queen, still in the prime of earthly existence, set off upon a voyage to the netherworld, in quest of eternal life. -

Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 47, 1961

THE JOURNAL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME47 DECEMBER 1961 PUBLISHED BY THE JOURNAL OF Egyptian Archaeology VOLUME 47 PUBLISHED BY THE EGYPT EXPLORATION SOCIETY 2 HINDE STREET, MANCHESTER SQUARE, LONDON, W.l I961 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL FOREWORD ....... 1 THE STELA OF MERER IN CRACOW .... Jaroslav Cerny 5 AN UNUSUAL STELA FROM ABYDOS .... K. A. Kitchen 10 A FRAGMENT OF A PUNT SCENE ..... Nina M. Davies 19 THE PLAN OF TOMB 55 IN THE VALLEY OF THE KINGS Elizabeth Thomas 24 ONCE AGAIN THE SO-CALLED COFFIN OF AKHENATEN H. W. Fairman 25 THE TOMB OF AKHENATEN AT THEBES .... Cyril Aldred 4i APPENDIX . A. T. Sandison 60 FINDS FROM 'THE TOMB OF QUEEN TIYE' IN THE SWANSEA MUSEUM ........ Kate Bosse-Griffiths 66 SOME SEA-PEOPLES ....... G. A. Wainwright 7I THE EGYPTIAN MEMNON ...... Sir Alan Gardiner 91 THE ALLEGED SEMITIC ORIGINAL OF THE Wisdom of Amenemope ........ Ronald J. Williams 100 NOTES ON PTOLEMAIC CHRONOLOGY. II ... T. C. Skeat 107 THE DEATH OF CLEOPATRA VII J. Gwyn Griffiths "3 '0 "KAPAKAAAOS" KOSMOKPATQP . Abd el-Mohsen el-Khachab 119 THE AIOAK02 OF ALEXANDRIA P. M. Fraser BIBLIOGRAPHY: GRAECO-ROMAN EGYPT: GREEK INSCRIP 134 TIONS (I960) . P. M. Fraser J BRIEF COMMUNICATIONS : Note on the supposed beginning of a Sothic period under Sethos I 39 by Jaroslav Cerny, p. 150; A supplement to Janssen's list of dogs' names, by Henry G Fischer, p. 152; Hry-r a word for infant, by Hans Goedicke, p. 154; Seth as a fool, by Hans Goedicke, p. 154; A sportive writing of the interrogative in + m, by Hans Goedicke, P-I55- REVIEWS SIEGFRIED MORENZ, Agyptische Religion Reviewed by J. -

Pyramid of Unas : 11 Unas (Unis)(C. 2356

11 : Pyramid of Unas . Unas (Unis)(c. 2356 - 2323 BC) was the last king of the Fifth Dynasty. The pyramid dedicated to this king lies to the south of the Step Pyramid. The Pyramid of Unas (Unis) is in poor condition however, the burial chambers are worth the visit. In this chamber, you will find the earliest Egyptian funerary texts carved into the walls and filled with a blue pigment. These are referred to as the Pyramid Texts. They are the rituals and hymns that were said during the in the walls of the pyramids. burial. Before this time, nothing was engraved The pyramid, when it was complete stood about 62 ft (18.5 m). The core of the pyramid was loose blocks and rubble and the casing was of limestone. Today it looks like a pile of dirt and rubble, especially from the east side. Although the outside of the pyramid is in ruin, the inside is still sound. You may enter the pyramid from the north side. Trying to block the way, are three huge slabs of granite. Once inside the chamber, you will find the Pyramid Texts that were intended to help the pharaoh's soul in the afterworld. They were to help the soul find Re, the sun god. 12 : Pyramid of Pepi II . South Saqqara is completely separate from Saqqara. It is located about 1km south of the pyramid of Sekhemkhet, which is the most southern of all the pyramids in Saqqara. South Saqqara was founded in the 6th Dynasty (2345 - 2181 BC) by the pharaohs. -

Catalog SCIROCCO

Главная Назад Каталог пирамид. Каталог ШИРОКО Дата публикации: 2013г. Версия 3 от 13.09.2013 [email protected] Кат. N: PYReg001.GIZ01.LpsIV Название: Пирамида фараона Хеопса (Cheops) Другие названия: Куфу(Khufu), Великая(Great); Лепсиуса IV(Lepsius IV), Kheops Координаты: 29°58'45.03''N 31°08'03.69''E Ориентир: Египет, Каир, Гиза (Egypt, Cairo, Giza) Форма: гладкая, наклон: 51.89° Материал: , камень (известняк) Размеры,м: 230x230x146.5 Азимут, °: 0 Коментарий:Самая большая из рукотворных пирамид M01, M02 000, 001, 002, 003, 004, 005, 006, Кат. N: PYReg002.GIZ02.LpsVIII Название: Пирамида фараона Хафры (Khafre) Другие названия: Хефрена(Khephren); Урт-Хафра (Hurt-Khafre); Лепсиус VIII(Lepsius VIII) Координаты: 29°58'34"N 31°07'51"E Ориентир: Египет, Каир, Гиза (Egypt, Cairo, Giza) Форма: гладкая, наклон: 53.12° Материал: , камень (известняк) Размеры, м: 215.3x215.3x143.5 Азимут, °: 0 Коментарий: M01, M02 000, 001, 002, 003 004, 005, Кат. N: PYReg003.GIZ03.LpsIX Название: Пирамида фараона Менкаура(Menkaure) Другие названия: Микерина (Menkaure), Лепсиус IX (Lepsius IX); Херу; Координаты: 29°58'21"N 31°07'42"E Ориентир: Египет, Каир, Гиза (Egypt, Cairo, Giza) Форма: гладкая, наклон: 51.72° Материал: , камень (известняк) Размеры, м: 102.2x104.6x65.5 Азимут, °: 0 Коментарий: M01, M02 000, 001, 002, 003, 004, 005, 006, 007, 008, 009, 010, 011, 012, 013, 014, 015, 016, 017, 018, Кат. N: PYReg004.GIZ04.LpsV Название:Пирамида царицы Хетепхерес I (Hetepheres I) фараона Хеопса. Другие названия: Царица Хетепхерес I (Queen Hetepheres I) ; G I-a; Лепсиус V (Lepsius V); Координаты: 29°58'43.80"N, 31° 8'10.23"E Ориентир: Египет, Каир, Гиза (Egypt, Cairo, Giza) Форма: гладкая, наклон: 51.72° Материал: , камень Размеры, м: 47.5x47.5x30.1(?) Азимут, °: 0 Коментарий: M01, M02 000, 001, 002, 003, 004, 005, 006, 007, 008, 009, Кат. -

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour

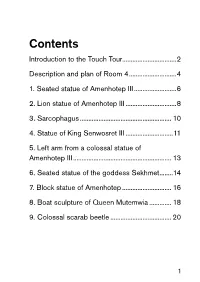

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour................................2 Description and plan of Room 4 ............................4 1. Seated statue of Amenhotep III .........................6 2. Lion statue of Amenhotep III ..............................8 3. Sarcophagus ...................................................... 10 4. Statue of King Senwosret III ............................11 5. Left arm from a colossal statue of Amenhotep III .......................................................... 13 6. Seated statue of the goddess Sekhmet ........14 7. Block statue of Amenhotep ............................. 16 8. Boat sculpture of Queen Mutemwia ............. 18 9. Colossal scarab beetle .................................... 20 1 Introduction to the Touch Tour This tour of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery is a specially designed Touch Tour for visitors with sight difficulties. This guide gives you information about nine highlight objects in Room 4 that you are able to explore by touch. The Touch Tour is also available to download as an audio guide from the Museum’s website: britishmuseum.org/egyptiantouchtour If you require assistance, please ask the staff on the Information Desk in the Great Court to accompany you to the start of the tour. The sculptures are arranged broadly chronologically, and if you follow the tour sequentially, you will work your way gradually from one end of the gallery to the other moving through time. Each sculpture on your tour has a Touch Tour symbol beside it and a number. 2 Some of the sculptures are very large so it may be possible only to feel part of them and/or you may have to move around the sculpture to feel more of it. If you have any questions or problems, do not hesitate to ask a member of staff. -

Who Was Who at Amarna

1 Who was Who at Amarna Akhenaten’s predecessors Amenhotep III: Akhenaten’s father, who ruled for nearly 40 years during the peak of Egypt’s New Kingdom empire. One of ancient Egypt’s most prolific builders, he is also known for his interest in the solar cult and promotion of divine kingship. He was buried in WV22 at Thebes, his mummy later cached with other royal mummies in the Tomb of Amenhotep II (KV 35) in the Valley of the Kings. Tiye: Amenhotep III’s chief wife and the mother of Akhenaten. Her parents Yuya and Tjuyu were from the region of modern Akhmim in Egypt’s south. She may have lived out her later years at Akhetaten and died in the 14th year of Akhenaten’s reign. Funerary equipment found in the Amarna Royal Tomb suggests she was originally buried there, although her mummy was later moved to Luxor and is perhaps to be identified as the ‘elder lady’ from the KV35 cache. Akhenaten and his family Akhenaten: Son and successor of Amenhotep III, known for his belief in a single solar god, the Aten. He spent most of his reign at Akhetaten (modern Amarna), the sacred city he created for the Aten. Akhenaten died of causes now unknown in the 17th year of his reign and was buried in the Amarna Royal Tomb. His body was probably relocated to Thebes and may be the enigmatic mummy recovered in the early 20th century in tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings. Nefertiti: Akhenaten’s principal queen. Little is known of her background, although she may also have come from Akhmim. -

Who's Who in Ancient Egypt

Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Available from Routledge worldwide: Who’s Who in Ancient Egypt Michael Rice Who’s Who in the Ancient Near East Gwendolyn Leick Who’s Who in Classical Mythology Michael Grant and John Hazel Who’s Who in World Politics Alan Palmer Who’s Who in Dickens Donald Hawes Who’s Who in Jewish History Joan Comay, new edition revised by Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok Who’s Who in Military History John Keegan and Andrew Wheatcroft Who’s Who in Nazi Germany Robert S.Wistrich Who’s Who in the New Testament Ronald Brownrigg Who’s Who in Non-Classical Mythology Egerton Sykes, new edition revised by Alan Kendall Who’s Who in the Old Testament Joan Comay Who’s Who in Russia since 1900 Martin McCauley Who’s Who in Shakespeare Peter Quennell and Hamish Johnson Who’s Who in World War Two Edited by John Keegan Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Michael Rice 0 London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. © 1999 Michael Rice The right of Michael Rice to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.