Life History of Wild Rainbow Trout in Missouri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fishing on the Eleven Point River

FISHING ON THE ELEVEN POINT RIVER Fishing the Eleven Point National Scenic River is a very popular recreation activity on the Mark Twain National Forest. The river sees a variety of users and is shared by canoes and boats, swimmers, trappers, and anglers. Please use caution and courtesy when encountering another user. Be aware that 25 horsepower is the maximum boat motor size allowed on the Eleven Point River from Thomasville to "the Narrows" at Missouri State Highway 142. Several sections of the river are surrounded by private land. Before walking on the bank, ask the landowners for permission. Many anglers today enjoy the sport of the catch and fight, but release the fish un-harmed. Others enjoy the taste of freshly caught fish. Whatever your age, skill level or desire, you should be aware of fishing rules and regulations, and a little natural history of your game. The Varied Waters The Eleven Point River, because of its variety of water sources, offers fishing for both cold and warm-water fish. Those fishing the waters of the Eleven Point tend to divide the river into three distinctive areas. Different fish live in different parts of the river depending upon the water temperature and available habitat. The upper river, from Thomasville to the Greer Spring Branch, is good for smallmouth bass, longear sunfish, bluegill, goggle-eye (rock bass), suckers, and a few largemouth bass. This area of the river is warmer and its flow decreases during the summer. The river and fish communities change where Greer Spring Branch enters the river. -

2005 MO Cave Comm.Pdf

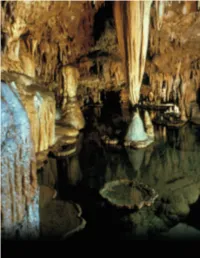

Caves and Karst CAVES AND KARST by William R. Elliott, Missouri Department of Conservation, and David C. Ashley, Missouri Western State College, St. Joseph C A V E S are an important part of the Missouri landscape. Caves are defined as natural openings in the surface of the earth large enough for a person to explore beyond the reach of daylight (Weaver and Johnson 1980). However, this definition does not diminish the importance of inaccessible microcaverns that harbor a myriad of small animal species. Unlike other terrestrial natural communities, animals dominate caves with more than 900 species recorded. Cave communities are closely related to soil and groundwater communities, and these types frequently overlap. However, caves harbor distinctive species and communi- ties not found in microcaverns in the soil and rock. Caves also provide important shelter for many common species needing protection from drought, cold and predators. Missouri caves are solution or collapse features formed in soluble dolomite or lime- stone rocks, although a few are found in sandstone or igneous rocks (Unklesbay and Vineyard 1992). Missouri caves are most numerous in terrain known as karst (figure 30), where the topography is formed by the dissolution of rock and is characterized by surface solution features. These include subterranean drainages, caves, sinkholes, springs, losing streams, dry valleys and hollows, natural bridges, arches and related fea- Figure 30. Karst block diagram (MDC diagram by Mark Raithel) tures (Rea 1992). Missouri is sometimes called “The Cave State.” The Mis- souri Speleological Survey lists about 5,800 known caves in Missouri, based on files maintained cooperatively with the Mis- souri Department of Natural Resources and the Missouri Department of Con- servation. -

Recharge Area of Selected Large Springs in the Ozarks

RECHARGE AREA OF SELECTED LARGE SPRINGS IN THE OZARKS James W. Duley Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Cecil Boswell Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Jerry Prewett Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Abstract parently passing under a gaining segment of the 11 Ongoing work by the Missouri Geological Survey Point River, ultimately emerging more than four kilo- (MGS) is refining the known recharge areas of a number meters to the southeast. This and other findings raise of major springs in the Ozarks. Among the springs be- questions about how hydrology in the study area may ing investigated are: Mammoth Spring (Fulton County, be controlled by deep-seated mechanisms such as basal Arkansas), and the following Missouri springs: Greer faulting and jointing. Research and understanding would Spring (Oregon County), Blue Spring (Ozark County), be improved by 1:24,000 scale geologic mapping and Blue/Morgan Spring Complex (Oregon County), Boze increased geophysical study of the entire area. Mill Spring (Oregon County), two different Big Springs (Carter and Douglas County) and Rainbow/North Fork/ Introduction Hodgson Mill Spring Complex (Ozark County). Pre- In the latter half of the 20th century, the US Forest Ser- viously unpublished findings of the MGS and USGS vice and the National Park Service began serious efforts are also being used to better define recharge areas of to define the recharge areas of some of the largest springs Greer Spring, Big Spring (Carter County), Blue/Morgan in the Ozarks of south central Missouri using water trac- Spring Complex, and the Rainbow/ North Fork/Hodg- ing techniques. -

The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2016–2017 Paddle the Spring-Fed Rivers of Ozark National Forest South of Winona

So Much to Learn: The Ozark National Scenic Riverways and Its Karst Landscape BY QUINTA SCOTT 14 | The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2016–2017 Paddle the spring-fed rivers of Ozark National Forest south of Winona. It has two major tributaries: Scenic Riverways, the Current and its tributary, the Greer Spring and Hurricane Creek, a classic Ozark Jacks Fork. Montauk Spring, Welch Spring, Cave losing stream. Spring, Pulltite Spring, Round Spring, Blue Spring, Use your imagination to understand the and Big Spring are also Current tributaries. A second subterranean drainage of the three rivers. Consider Blue Spring and Alley Spring feed the Jacks Fork. Hurricane Creek, the losing stream with a Put in below at Akers, below Welch Spring, where topographic watershed of 116 square miles. Yes, it’s it is the sixth largest spring in the state and turns the a tributary to the Eleven Point River, but only its last Current from a lazy Ozark stream into a first-class mile carries surface water to the river. The rest seeps float. Don’t forget the Eleven Point, the Wild and into a subterranean system that carries water under Scenic River that flows through Mark Twain National the drainage divide between the Eleven Point and the Current to deliver water to Big Spring. The same holds true for Logan Creek, a losing stream that is a tributary to the Black River. Rain falls on Logan Creek, spills into the subterranean system, crosses under the surface divide between the Black and the Current, and delivers water to Blue Spring. Alley Spring draws from an amazing system of sinkholes and losing streams, including Spring Valley Creek, which becomes a tributary of the Current, once it passes through Round Spring. -

U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017

A Product of the Water Availability and Use Science Program Prepared in cooperation with the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Texas at San Antonio and hosted by the Student Geological Society and student chapters of the Association of Petroleum Geologists and the Association of Engineering Geologists U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017 Edited By Eve L. Kuniansky and Lawrence E. Spangler Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5023 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Kuniansky, E.L., and Spangler, L.E., eds., 2017, U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5023, 245 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20175023. -

Developing a New Lead District in Missouri: a Conflict Between Maintaining a Mining Heritage and Preserving Ecological Integrity on the Ozark Highland

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1992 Developing a new lead district in Missouri: A conflict between maintaining a mining heritage and preserving ecological integrity on the Ozark Highland Douglas J. Hawes-Davis The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hawes-Davis, Douglas J., "Developing a new lead district in Missouri: A conflict between maintaining a mining heritage and preserving ecological integrity on the Ozark Highland" (1992). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4746. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4746 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY Copying allowed as provided under provisions of the Fair Use Section of the U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW, 1976. Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author’s written consent. MontanaUniversity of DEVELOPING A NEW LEAD DISTRICT IN MISSOURI: A CONFLICT BETWEEN MAINTAINING A MINING HERITAGE AND PRESERVING ECOLOGICAL INTEGRITY ON THE OZARK HIGHLAND by Douglas J. Hawes-Davis B.A. DePauw University, Greencastle, Indiana, 1989 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1992 Approved-by ^ t S. -

A Study of Missouri Springs

Scholars' Mine Professional Degree Theses Student Theses and Dissertations 1935 A study of Missouri springs Harry Cloyd Bolon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/professional_theses Part of the Civil Engineering Commons Department: Recommended Citation Bolon, Harry Cloyd, "A study of Missouri springs" (1935). Professional Degree Theses. 242. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/professional_theses/242 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Degree Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF MISSOURI SPRINGS by liarry C. Bolon A ,T HE SIS submitted to the £aoulty of the SCIDOL OF MINES AND METALLURGY OF TEE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI in partial fulfillment of the work required for tbe DEGREE OF CIVIL ENGINEER Rolla, Mo. 1955 <3Te~.'~_r;fJ /d~~_. Approved b:Y:_--.,.. __ __.-....-__ ~ . Professor of Civil Engineering TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Introduction•••••••••••.••-••.•-. •••••.•..••.••.••• .. • . • • 1 Importance of Springs and Their Worth to Missouri........ 2 Recreation••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ~ •••• 2 Power••••••••••••••••'. •••••••••••••••••••••••• •.• • • • • 5 Watar Supply........................................ 5 Commercial Uses.................................... -

Missouri's Pioneer in Sustainable Forestry

Pioneer Forest, Missouri’s largest private landholding at some 150,000 acres, has been a lodestar of sustainability during more than half a century of dramatic oscillation in forest management goals and techniques nationwide. Its owner, Leo Drey, initially intended to demonstrate the potential for developing a viable natural resource-based economy in the Missouri Ozarks. But through his remarkably consistent vision and well documented management by single-tree selection, the forest came to represent a model of sustainability for other private forest holdings and a workable alternative to even-aged management regimes being promulgated on federal and state forests. On July 6, 2004, Leo Drey and his wife Kay signed over virtually the entire forest to the L-A-D Foundation, the most spectacular gift of real estate ever in Missouri, in order to assure that the forest will continue to lead and inspire into the future. Missouri’s Pioneer in Sustainable Forestry eo Drey purchased his first tract of Ozark timberland in eastern Shannon County on March 8, 1951. It was 1407 acres of oak, much of it butt rotten, Lbut it had some pine reproduction plus some larger pines; there was not much grazing, there were no squatters or tenants, and theft was not bad. The owner wanted about $4 an acre. So said Drey’s notes, to the treasurer of a shoe company before deciding to follow his scratched in pencil on an envelope, along with a sketch map of calling to forest conservation. His father had died when Leo was parcels that were included or not. -

A Geochemical and Statistical Investigation of the Big Four Springs Region in Southern Missouri

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Summer 2020 A Geochemical and Statistical Investigation of the Big Four Springs Region in Southern Missouri Jordan Jasso Vega Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Applied Statistics Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Geology Commons, Hydrology Commons, Multivariate Analysis Commons, and the Statistical Models Commons Recommended Citation Vega, Jordan Jasso, "A Geochemical and Statistical Investigation of the Big Four Springs Region in Southern Missouri" (2020). MSU Graduate Theses. 3558. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3558 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A GEOCHEMICAL AND STATISTICAL INVESTIGATION OF THE BIG FOUR SPRINGS REGION IN SOUTHERN MISSOURI -

2013 Annual Report of the L-A-D Foundation October 2013 1

Annual Report 2013 Annual Report of the L-A-D Foundation October 2013 1 COVER PHOTO: Dillard Mill State Historic Site in early morning light, 2012, by Phil Kamp and printed with permission. The mill and surrounding property is owned by the L-A-D Foundation and, since 1975, has been leased to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources to operate as a Missouri State Park. 2013 Annual Report of the L-A-D Foundation 2 ANNUAL REPORT of the L-A-D Foundation October 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS From the President 5 Pioneer Forest Management 6 Land Consolidation 10 TO BE UPDATE . Research 11 Education and Outreach 14 Recreation and Natural Areas 16 Grantmaking and Community Support 24 Public Policy Issues 27 Administrative Issues 30 Appendices 32 Glossary of Terms 35 PHOTOGRAPHS AND IMAGES: Photo and image credit information used in this report is found with each image; all are printed from digital files, and those not originating with the Foundation have been given to us for our use and are reproduced here with permission. The maps we have used are taken from digital map files of Missouri that are renderings of the U.S. Geological Survey topographic quadrangles and are produced using ArcMap software from ESRI. Other maps are produced using ArcGIS 10.1, National Geographic TOPO! Software, Google Maps, or Google Earth. 2013 Annual Report of the L-A-D Foundation 3 L-A-D Foundation “Incorporated in 1962, the L-A-D Foundation is a Missouri private operating foundation dedicated to sustainable forest management, protection of exemplary natural and cultural areas in Missouri, and providing support and advocacy for projects and policies that have a positive influence in the Missouri Ozark region.” Leo Drey began acquisition of forest land in the Missouri Ozarks in 1951. -

Missouri Springs: Power, Purity and Promise

Missouri Springs: Power, Purity and Promise By Loring Bullard © Watershed Press Design by: Kelly Guenther Missouri Springs: Power, Purity and Promise By: Loring Bullard Introduction It is a bragging right that may be as old as This property of springs—their sudden land ownership itself. “I have a spring on my and hitherto unexplainable appearance— place that never runs dry.” The intimation is adds to their mysterious aura. Among that of all the springs around, there is some- our ancestors, speculation about spring thing unique—something special—about my origins formed a rather sizeable body of spring. Landowners have perhaps always folklore. While scientists can now explain viewed springs differently than nearby creeks. most of these formerly mystifying Unlike a creek that arises surreptitiously on the properties, the allure of springs remains. property of others before passing through their People will probably always be land, a spring begins on their property. They intrigued—even mesmerized—by springs. can say that they own it. From an unseen, un- The human attraction to springs is obvious source, it literally springs, full blown, extremely durable. Springs guided the from the depths of the earth. A spring can truly habitation patterns and movements of be the source of a creek. Native Americans, just as they did the Marker at Liberty, Missouri (Photo by Author) Missouri Springs: Power, Purity and Promise 3 Introduction An Ozark Spring (Courtesy Western Historical Manuscript Collection) later arriving settlers. Indian villages and hunting public water supplies. After all, these camps were usually located near perennial fortuitous emanations from the earth springs. -

Species Status Assessment Report for The

Species Status Assessment Report for the Coldwater Crayfish ( Faxonius eupunctus ) and Eleven Point River Crayfish ( Faxonius wagneri ) Coldwater Crayfish (left); Photo: Chris Lukhaup, Missouri Department of Conservation Eleven Point River Crayfish (right); Photo: Christopher Taylor, Illinois Natural History Survey U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service December 7, 2018 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by Trisha Crabill (Missouri Ecological Services Field Office), Laura Ragan (Midwest Regional Office), and Jonathan JaKa (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Headquarters) with assistance from Alyssa Bangs (Arkansas Ecological Services Field Office), Scott Hamilton (Missouri Ecological Services Field Office), Joshua Hundley (Missouri Ecological Services Field Office), Ashton Jones (Missouri Ecological Services Field Office), and Rachel Croft (Missouri Ecological Services Field Office). We greatly appreciate the following species experts who provided data and extensive input on various aspects of the SSA analysis, including a technical review of the draft report: Robert DiStefano (Missouri Department of Conservation), Dr. Daniel Magoulick (University of Arkansas), Dr. Christopher Taylor ( Illinois Natural History Survey) , Brian Wagner (Arkansas Game and Fish Commission), and Dr. Jacob Westhoff (Missouri Department of Conservation). We also thank Dr. James Fetzner (Carnegie Museum of Natural History) for reviewing the draft report and providing information on the Faxonius wagneri and F. roberti species delineations. Lastly, we thank Dr. Zachary Loughman (West Liberty University) and Christopher Rice (Missouri Department of Conservation) for providing a technical review of the draft report. Suggested citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for the Coldwater Crayfish (F axonius eupunctus) and Eleven Point River Crayfish (F axonius wagneri ). Version 1.0, December 2018.