Eleven Point River Watershed and Inventory Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fishing on the Eleven Point River

FISHING ON THE ELEVEN POINT RIVER Fishing the Eleven Point National Scenic River is a very popular recreation activity on the Mark Twain National Forest. The river sees a variety of users and is shared by canoes and boats, swimmers, trappers, and anglers. Please use caution and courtesy when encountering another user. Be aware that 25 horsepower is the maximum boat motor size allowed on the Eleven Point River from Thomasville to "the Narrows" at Missouri State Highway 142. Several sections of the river are surrounded by private land. Before walking on the bank, ask the landowners for permission. Many anglers today enjoy the sport of the catch and fight, but release the fish un-harmed. Others enjoy the taste of freshly caught fish. Whatever your age, skill level or desire, you should be aware of fishing rules and regulations, and a little natural history of your game. The Varied Waters The Eleven Point River, because of its variety of water sources, offers fishing for both cold and warm-water fish. Those fishing the waters of the Eleven Point tend to divide the river into three distinctive areas. Different fish live in different parts of the river depending upon the water temperature and available habitat. The upper river, from Thomasville to the Greer Spring Branch, is good for smallmouth bass, longear sunfish, bluegill, goggle-eye (rock bass), suckers, and a few largemouth bass. This area of the river is warmer and its flow decreases during the summer. The river and fish communities change where Greer Spring Branch enters the river. -

Activity Guide 75+ Things to See and Do

Activity Guide 75+ Things to See and Do in and around Pocahontas and Randolph County Arkansas ! USA Experience The Lesmeister, a well- appointed retreat offering a restful escape from your busy life, or an active time spent seeing and doing in a classic American hill town. The choice is yours! • For ambiance, each living area has either a wood-burning stove or gas fireplace. • Bedrooms feature king size beds with high-thread count sheets • Enjoy private bathrooms with heated floors, ultra-clean Sanijet spa tubs, a shower, flat screen TV, towel warmer, toilet with heated seat/Bidet with warmed water, and a skylight to let the natural light come in. Make Secure Online Reservations 24/7 at ArkansasGuestHouse.com 208 N Marr Street, Pocahontas, Arkansas 501-291-1233 The perfect base for a visit to historic Pocahontas! Activity Guide Copyright © 2012-17 by ARSoft LLC. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Things to See & Do in Downtown Pocahontas Historic District Walking Tour. 7 NoMa Art and Entertainment District. 7 Downtown Playhouse.. 7 Bella Piazza Italian Restaurant. 8 Carroll’s Variety Store and Flea Market.. 8 1872 Randolph County Courthouse.. 9 Capture of Confederate General Jeff Thompson. 9 Arkansas’ Only Quilt Trail. 10 Studio B Salon and Day Spa. 11 Black River Beads, Pottery, and Glass Blowing. 11 Randolph County Heritage Museum. 11 The Treasure Trunk Eclectic Shopping. 12 Black River Overlook Park, Lover’s Lock Lane, and The Pocahontas Civil War River Walk Memorial. 12 Futrell’s Old Time Hardware. 14 R. J. Reynolds-Pearcy Art Gallery. 14 Arkansas’ Oldest Barber Shop. -

Fishes of Randolph County, Arkansas Steve M

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 31 Article 8 1977 Fishes of Randolph County, Arkansas Steve M. Bounds Arkansas State University John K. Beadles Arkansas State University Billy M. Johnson Arkansas State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Bounds, Steve M.; Beadles, John K.; and Johnson, Billy M. (1977) "Fishes of Randolph County, Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 31 , Article 8. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol31/iss1/8 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ! Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 31 [1977], Art. 8 Fishes ofRandolph County, Arkansas STEVE M. BOUNDS,' JOHN K.BEADLESand BILLYM.JOHNSON Divisionof Biological Sciences, Arkansas State University I State University, Arkansas 72467 ! ABSTRACT Asurvey of the fishes of Randolph County in northcentral Arkansas was made between June 1973 and March 1977. Field collections, literature records, and museum specimens re- n vealed the ichthyofauna of Randolph County to be composed of 128 species distributed among 24 families. -

Missouri Conservationist July 2021

VOLUME 82, ISSUE 7, JULY 2021 MISSOURI SERVING NATURE & YOU CONSERVATIONIST VIEWING W ILDLIFE HUNTING CAMPING LOUNGING RUNNING & HIKING BIKING ARCHERY & SHOO TING STARGAZING FISHING SWIMMING mdc.mo.gov/NeverLoseTouch For ways to reconnect with nature, visit visit nature, with reconnect to ways For . Never Lose Touch Lose Never . and again, It’s time to make that connection connection that make to time It’s nature and exploring Missouri. exploring and nature to give back while being out in in out being while back give to nature. There are so many ways ways many so are There nature. VIEWING W ILDLIFE HUNTING CAMPING LOUNGING RUNNING & HIKING to helping people connect with with connect people helping to up streams and planting trees trees planting and streams up efforts in Missouri, from cleaning cleaning from Missouri, in efforts huge impact on conservation conservation on impact huge it thriving. Volunteers make a a make Volunteers thriving. it needs to be cared for to keep keep to for cared be to needs Nature is amazing. It also also It amazing. is Nature with nature? with time you connected connected you time When was the last last the was When BIKING ARCHERY & SHOO TING STARGAZING FISHING SWIMMING MISSOURI CONSERVATIONIST JULY 2021 Contents VOLUME 82, ISSUE 7 10 ON THE COVER Bushwhacker Lake Conservation Area : DAVID STONNER 16–35mm lens, f/11 1/15 sec, ISO 100 GOVERNOR Michael L. Parson THE CONSERVATION COMMISSION CHAIR Don C. Bedell VICE CHAIR Wm. L. (Barry) Orscheln SECRETARY Mark L. McHenry MEMBER Steven D. Harrison DIRECTOR Sara -

A Legacy of Neglect: the Ozark National Scenic Riverways

A Legacy of Neglect: The Ozark National Scenic Riverways Susan Flader Missouri’s Current River and its tributary, the Jacks Fork, were the nation’s first fed- erally protected rivers. Congressionally authorized in 1964 as the Ozark National Scenic Riverways (ONSR), they served as a prototype for the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968. But in May 2011 ONSR was identified by American Rivers as one of America’s ten most endangered rivers, owing to a history of inadequate management by the National Park Service (NPS). The spring-fed, bluff-lined Current and Jacks Fork are the preeminent “float streams” in a state where floating, fishing, and camping by johnboat or canoe have long been favorite pastimes (Figure 1). The state’s first Republican governor since Reconstruction, Herbert Hadley, led well-publicized float trips on Current River as early as 1909 in an effort to pro- mote tourism and build support for a state park system. When Missouri acquired its first state parks in 1924, they included Round Spring and Big Spring on the Current River and Alley Spring on the Jacks Fork. The rivers early attracted admirers from afar; Aldo Leopold came from Wisconsin in 1926 to float the Current from Van Buren to Doniphan with his brothers (Leopold 1953; Figure 2), then in 1929 bought a shanty on its bank as a base for annual hunts, years before he acquired his celebrated shack in the sand country of Wisconsin. Like many other rivers that eventually won designation as national wild and scenic rivers, the Current was threatened by proposed hydroelectric dams. -

Fishes of the Eleven Point River Within Arkansas Michael B

Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science Volume 31 Article 19 1977 Fishes of the Eleven Point River Within Arkansas Michael B. Johnson Arkansas State University John K. Beadles Arkansas State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Michael B. and Beadles, John K. (1977) "Fishes of the Eleven Point River Within Arkansas," Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science: Vol. 31 , Article 19. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol31/iss1/19 This article is available for use under the Creative Commons license: Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-ND 4.0). Users are able to read, download, copy, print, distribute, search, link to the full texts of these articles, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science, Vol. 31 [1977], Art. 19 Fishes of the Eleven Point River Within Arkansas B.MICHAELJOHNSON and JOHN K.BEADLES Division of Biological Sciences Arkansas State University State University, Arkansas 72467 ABSTRACT A survey of the fishes of the Eleven Point River and its tributaries was made between 31 January 1976 and 13 February 1977. -

2005 MO Cave Comm.Pdf

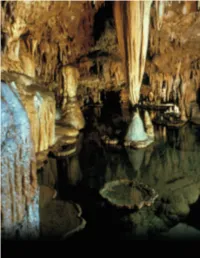

Caves and Karst CAVES AND KARST by William R. Elliott, Missouri Department of Conservation, and David C. Ashley, Missouri Western State College, St. Joseph C A V E S are an important part of the Missouri landscape. Caves are defined as natural openings in the surface of the earth large enough for a person to explore beyond the reach of daylight (Weaver and Johnson 1980). However, this definition does not diminish the importance of inaccessible microcaverns that harbor a myriad of small animal species. Unlike other terrestrial natural communities, animals dominate caves with more than 900 species recorded. Cave communities are closely related to soil and groundwater communities, and these types frequently overlap. However, caves harbor distinctive species and communi- ties not found in microcaverns in the soil and rock. Caves also provide important shelter for many common species needing protection from drought, cold and predators. Missouri caves are solution or collapse features formed in soluble dolomite or lime- stone rocks, although a few are found in sandstone or igneous rocks (Unklesbay and Vineyard 1992). Missouri caves are most numerous in terrain known as karst (figure 30), where the topography is formed by the dissolution of rock and is characterized by surface solution features. These include subterranean drainages, caves, sinkholes, springs, losing streams, dry valleys and hollows, natural bridges, arches and related fea- Figure 30. Karst block diagram (MDC diagram by Mark Raithel) tures (Rea 1992). Missouri is sometimes called “The Cave State.” The Mis- souri Speleological Survey lists about 5,800 known caves in Missouri, based on files maintained cooperatively with the Mis- souri Department of Natural Resources and the Missouri Department of Con- servation. -

Recharge Area of Selected Large Springs in the Ozarks

RECHARGE AREA OF SELECTED LARGE SPRINGS IN THE OZARKS James W. Duley Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Cecil Boswell Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Jerry Prewett Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Abstract parently passing under a gaining segment of the 11 Ongoing work by the Missouri Geological Survey Point River, ultimately emerging more than four kilo- (MGS) is refining the known recharge areas of a number meters to the southeast. This and other findings raise of major springs in the Ozarks. Among the springs be- questions about how hydrology in the study area may ing investigated are: Mammoth Spring (Fulton County, be controlled by deep-seated mechanisms such as basal Arkansas), and the following Missouri springs: Greer faulting and jointing. Research and understanding would Spring (Oregon County), Blue Spring (Ozark County), be improved by 1:24,000 scale geologic mapping and Blue/Morgan Spring Complex (Oregon County), Boze increased geophysical study of the entire area. Mill Spring (Oregon County), two different Big Springs (Carter and Douglas County) and Rainbow/North Fork/ Introduction Hodgson Mill Spring Complex (Ozark County). Pre- In the latter half of the 20th century, the US Forest Ser- viously unpublished findings of the MGS and USGS vice and the National Park Service began serious efforts are also being used to better define recharge areas of to define the recharge areas of some of the largest springs Greer Spring, Big Spring (Carter County), Blue/Morgan in the Ozarks of south central Missouri using water trac- Spring Complex, and the Rainbow/ North Fork/Hodg- ing techniques. -

The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2016–2017 Paddle the Spring-Fed Rivers of Ozark National Forest South of Winona

So Much to Learn: The Ozark National Scenic Riverways and Its Karst Landscape BY QUINTA SCOTT 14 | The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2016–2017 Paddle the spring-fed rivers of Ozark National Forest south of Winona. It has two major tributaries: Scenic Riverways, the Current and its tributary, the Greer Spring and Hurricane Creek, a classic Ozark Jacks Fork. Montauk Spring, Welch Spring, Cave losing stream. Spring, Pulltite Spring, Round Spring, Blue Spring, Use your imagination to understand the and Big Spring are also Current tributaries. A second subterranean drainage of the three rivers. Consider Blue Spring and Alley Spring feed the Jacks Fork. Hurricane Creek, the losing stream with a Put in below at Akers, below Welch Spring, where topographic watershed of 116 square miles. Yes, it’s it is the sixth largest spring in the state and turns the a tributary to the Eleven Point River, but only its last Current from a lazy Ozark stream into a first-class mile carries surface water to the river. The rest seeps float. Don’t forget the Eleven Point, the Wild and into a subterranean system that carries water under Scenic River that flows through Mark Twain National the drainage divide between the Eleven Point and the Current to deliver water to Big Spring. The same holds true for Logan Creek, a losing stream that is a tributary to the Black River. Rain falls on Logan Creek, spills into the subterranean system, crosses under the surface divide between the Black and the Current, and delivers water to Blue Spring. Alley Spring draws from an amazing system of sinkholes and losing streams, including Spring Valley Creek, which becomes a tributary of the Current, once it passes through Round Spring. -

Water Resources of Randolph and Lawrence Counties, Arkansas

Water Resources of Randolph and Lawrence Counties, Arkansas GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1879-B Prepared in cooperation with the Arkansas Geological Commission Water Resources of Randolph and Lawrence Counties, Arkansas By A. G. LAMONDS, MARION S. MINES, and RAYMOND 0. PLEBUCH CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1879-B Prepared in cooperation with the Arkansas Geological Commission UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1969 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Pr'nting Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 30 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract_ ----_-__--_--_--_-_-_--_-____-___----________-_____.-_- Bl Introduction._____________________________________________________ 2 Purpose.__--_____--_-____-__--________________________-___-_- 2 Acknowledgments. _ ___________________________________________ 2 The area.____________________________________________________ ? Surface-water resources.._-----____-_-_-_-___-_-_-_______________--_ ? Availability. __________________________________________________ fi Low-flow frequency._______________________________________ 5 Flow duration___________________________________________ 10 Floods.__________________________________________________ 12 Quality. ________------______--_-____._---____._-__-____-_-_- 14 Chemical and physical quality.-_____-_-___-___-_-_-_____-__ 14 Bacterial quality-_________________________________________ -

Species Status Assessment for Spring River Crayfish

Species Status Assessment Report for the Spring River Crayfish ( Faxonius roberti) Spring River Crayfish; Photo: Christopher Taylor, Illinois Natural History Survey U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service December 7, 2018 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by Trisha Crabill (Missouri Ecological Services Field Office), Laura Ragan (Midwest Regional Office), and Jonathan JaKa (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Headquarters) with assistance from Alyssa Bangs (Arkansas Ecological Services Field Office) and the following individuals from the Missouri Ecological Services Field Office: Scott Hamilton, Joshua Hundley, Ashton Jones, and Kaitlyn Kelly. We greatly appreciate the species experts who provided data and extensive input on various aspects of the SSA analysis, including a technical review of the draft report: Robert DiStefano (Missouri Department of Conservation), Dr. Daniel Magoulick (University of Arkansas), Dr. Christopher Taylor (I llinois Natural History Survey) , Brian Wagner (Arkansas Game and Fish Commission), and Dr. Jacob Westhoff (Missouri Department of Conservation). We also thank Dr. James Fetzner (Carnegie Museum of Natural History) for reviewing the draft report and providing information on the Faxonius wagneri a nd F. roberti s pecies delineations. Lastly, we thank Dr. Zachary Loughman (West Liberty University) and Christopher Rice (Missouri Department of Conservation) for providing a technical review of the draft report. Suggested citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for the Spring River Crayfish (F axonius roberti) . Version 1.0, December 2018. Midwest Region, Bloomington, Minnesota. 64 pp. 2 Executive Summary This report summarizes results of a species status assessment (SSA) conducted for the Spring River Crayfish (F axonius roberti) to assess its viability. -

Truman State University Press

Truman State University Press front_BSAutumn.indd iii 9/29/08 10:05:32 AM Copyright © 2008 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri USA All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover art: Bryan Culpepper. Used by permission. Pen and ink drawings by Bryan Culpepper; used by permission. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Type: Papyrus digitized data © 2001 Agfa Monotype Corporation and Esselte Letraset Ltd.; a trademark of Esselte Corp. ITC Usherwood © 1990 Adobe Systems Inc.; a registered trademark of International Typeface Corp. Printed by: Edwards Brothers, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stepenoff, Bonnie, 1949– Big spring autumn / Bonnie Stepenoff. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-931112-86-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Ozark Mountains Region—Social life and customs. 2. Ozark Mountains Re- gion—Description and travel. 3. Big Spring (Carter County, Mo.) 4. Carter County (Mo.)—Social life and customs. 5. Carter County (Mo.)—Description and travel. 6. Natural history—Ozark Mountains Region. 7. Natural history—Missouri—Carter County. 8. Stepenoff, Bonnie, 1949—Diaries. I. Title. F472.O9S74 2008 977.8'892043092—dc22 [B] 2008032546 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. The paper in this publication meets or exceeds the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1992. front_BSAutumn.indd iv 9/29/08 8:58:29 AM Contents Drawings by Bryan Culpepper . viii Acknowledgments . ix Introduction . xi The Hills . .1 Part 1: Groundwork .