The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2016–2017 Paddle the Spring-Fed Rivers of Ozark National Forest South of Winona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fishing on the Eleven Point River

FISHING ON THE ELEVEN POINT RIVER Fishing the Eleven Point National Scenic River is a very popular recreation activity on the Mark Twain National Forest. The river sees a variety of users and is shared by canoes and boats, swimmers, trappers, and anglers. Please use caution and courtesy when encountering another user. Be aware that 25 horsepower is the maximum boat motor size allowed on the Eleven Point River from Thomasville to "the Narrows" at Missouri State Highway 142. Several sections of the river are surrounded by private land. Before walking on the bank, ask the landowners for permission. Many anglers today enjoy the sport of the catch and fight, but release the fish un-harmed. Others enjoy the taste of freshly caught fish. Whatever your age, skill level or desire, you should be aware of fishing rules and regulations, and a little natural history of your game. The Varied Waters The Eleven Point River, because of its variety of water sources, offers fishing for both cold and warm-water fish. Those fishing the waters of the Eleven Point tend to divide the river into three distinctive areas. Different fish live in different parts of the river depending upon the water temperature and available habitat. The upper river, from Thomasville to the Greer Spring Branch, is good for smallmouth bass, longear sunfish, bluegill, goggle-eye (rock bass), suckers, and a few largemouth bass. This area of the river is warmer and its flow decreases during the summer. The river and fish communities change where Greer Spring Branch enters the river. -

Guidebook for Field Trips for the Thirty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the North-Central Section of the Geological Society of America

Guidebook for Field Trips for the Thirty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the North-Central Section of the Geological Society of America April 23-24, 2001 David Malone, Editor ISGS Guidebook 33 2001 George H. Ryan, Governor Department of Natural Resources ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William W. Shilts, Chief EDITOR'S MESSAGE Greetings from the Executive Committee of the North Central Section of the Geological Society of America! As geologists, we all recognize the great importance of field experiences. This year's meeting includes a diverse and excellent set of field trips. Collectively, this year's field trips visit a broad spectrum of the geologic features of Illinois and Missouri that range in age from Precambrian to Quaternary. These trips present a number of new ideas and interpretations that will broaden the perspectives of all field trip participants. Your participation, interaction, and exchange of ideas with the field trip leaders are encouraged at all times These trips are the culmination of the time and energy freely given by a number of individuals. I would like to thank and recognize the field trip leaders for their hard work in planning the field trips and preparing the individual field guides. I would also like to thank the technical reviewers at Illinois State University and the Illinois State Geological Survey for their efforts. I appreciate the efforts of Jon Goodwin and the publication staff at the Illinois State Geological Survey for their substantial work in preparing this field guide. A special thanks goes out to the property owners who have been most helpful in planning these trips. -

2005 MO Cave Comm.Pdf

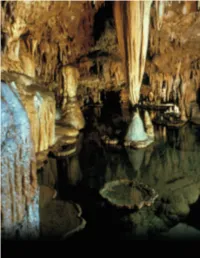

Caves and Karst CAVES AND KARST by William R. Elliott, Missouri Department of Conservation, and David C. Ashley, Missouri Western State College, St. Joseph C A V E S are an important part of the Missouri landscape. Caves are defined as natural openings in the surface of the earth large enough for a person to explore beyond the reach of daylight (Weaver and Johnson 1980). However, this definition does not diminish the importance of inaccessible microcaverns that harbor a myriad of small animal species. Unlike other terrestrial natural communities, animals dominate caves with more than 900 species recorded. Cave communities are closely related to soil and groundwater communities, and these types frequently overlap. However, caves harbor distinctive species and communi- ties not found in microcaverns in the soil and rock. Caves also provide important shelter for many common species needing protection from drought, cold and predators. Missouri caves are solution or collapse features formed in soluble dolomite or lime- stone rocks, although a few are found in sandstone or igneous rocks (Unklesbay and Vineyard 1992). Missouri caves are most numerous in terrain known as karst (figure 30), where the topography is formed by the dissolution of rock and is characterized by surface solution features. These include subterranean drainages, caves, sinkholes, springs, losing streams, dry valleys and hollows, natural bridges, arches and related fea- Figure 30. Karst block diagram (MDC diagram by Mark Raithel) tures (Rea 1992). Missouri is sometimes called “The Cave State.” The Mis- souri Speleological Survey lists about 5,800 known caves in Missouri, based on files maintained cooperatively with the Mis- souri Department of Natural Resources and the Missouri Department of Con- servation. -

Recharge Area of Selected Large Springs in the Ozarks

RECHARGE AREA OF SELECTED LARGE SPRINGS IN THE OZARKS James W. Duley Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Cecil Boswell Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Jerry Prewett Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Abstract parently passing under a gaining segment of the 11 Ongoing work by the Missouri Geological Survey Point River, ultimately emerging more than four kilo- (MGS) is refining the known recharge areas of a number meters to the southeast. This and other findings raise of major springs in the Ozarks. Among the springs be- questions about how hydrology in the study area may ing investigated are: Mammoth Spring (Fulton County, be controlled by deep-seated mechanisms such as basal Arkansas), and the following Missouri springs: Greer faulting and jointing. Research and understanding would Spring (Oregon County), Blue Spring (Ozark County), be improved by 1:24,000 scale geologic mapping and Blue/Morgan Spring Complex (Oregon County), Boze increased geophysical study of the entire area. Mill Spring (Oregon County), two different Big Springs (Carter and Douglas County) and Rainbow/North Fork/ Introduction Hodgson Mill Spring Complex (Ozark County). Pre- In the latter half of the 20th century, the US Forest Ser- viously unpublished findings of the MGS and USGS vice and the National Park Service began serious efforts are also being used to better define recharge areas of to define the recharge areas of some of the largest springs Greer Spring, Big Spring (Carter County), Blue/Morgan in the Ozarks of south central Missouri using water trac- Spring Complex, and the Rainbow/ North Fork/Hodg- ing techniques. -

Bedrock Units in Missouri and Parts of Adjacent States

Geochemistry of Bedrock Units in Missouri and Parts of Adjacent States By JON J. CONNOR and RICHARD J. EBENS GEOCHEMICAL SURVEY OF MISSOURI GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFES-SIONAL PAPER 954-F An examination of geochemical variability in rocks of Paleozoic and Precambrian ages UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1980 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Connor, Jon J. Geochemistry of bedrock units in Missouri and parts of adjacent states. (Geochemical survey of Missouri) (Geological Survey Professional Paper 954-F} Bibliography: p. 54 Supt. Docs. no.; I 19.16: 954-F 1. Rocks, Sedimentary. 2. Geology, Stratigraphic-Pre-Cambrian. 3. Geology, Stratigraphic-Paleozoic. 4. Geochemistry-Missouri. 5. Geochemistry-Middle West. I. Ebens, Richard J., joint author. II. Title. III. Series. IV. Series: United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 954-F For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-03307-1 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ............................................... F1 Geochemical variability ................................. F2'l Introduction ........................................... 1 Limestone and dolomite ............................. 21 Geologic setting ........................................ 2 Shale .............................................. 29 Sampling design ........................................ 6 Sandstone -

NM-Refs to Acquire

NM-refs to acquire I.e. References to Acquire Priority A | Priority B | Priority C | Priority D |Priority A. Highest priority –references are prioritized– 1. Bryan, Eliza (n.d.) Journal • No. 1 on the Compendium’s Ten Most Wanted. It is not known that such a journal exists or even existed. But EB’s letter (Bryan, 1816) to Lorenzo Dow in Dow (1848) is the best single eyewitness account of the 1811-12 earthquakes and the effects of the principal events, D1, J1, F1. The letter, four years after F1, contains a high level of detail, suggesting it was written from notes rather than from memory as she states. Moreover, Flint (Flint, 1826, Recollections…) describes her as cultured and educated like her mother Dinah Grey (Martin). 2. Lesieur, Godfrey (Map, 1836). "Lesieur’s Map" from Linn (1836) in Wetmore (1837) • No. 2 on the Compendium’s Ten Most Wanted. It refers to the map of the Bootheel/sunklands region prepared by Lesieur for Senator Lewis Linn for his report to the Committee on Commerce, 1 Feb 1836. Reference to the map is found in Linn (1836), reprinted in Wetmore (1837). This is probably the only map that could authoritatively show the St. Francis-Little River drainage basins and drainage pattern prior to 1811. 3. Speed, Mathias[Matthias] (2 March 1812). "From the Bairdstown (Kentucky) Repository" • No. 3 on the Compendium’s Ten Most Wanted. This is the original publication of Matthais (or Mathais) Speed’s famous letter recounting his flatboat passage from Island No. 9 to New Madrid on the morning of 7 Feb 1812. -

November 26, 1984 Reston, Virginia

^pf"3 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROCEEDINGS OF THE SYMPOSIUM ON "THE NEW MADRID SEISMIC ZONE" NOVEMBER 26, 1984 RESTON, VIRGINIA This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey publication standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the United States Government. Any use of trade names and trademarks in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. Reston, Virginia 1984 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROCEEDINGS OF THE SYMPOSIUM ON "THE NEW MADRID SEISMIC ZONE" November 26,1984 Reston, Virginia Convenor and Organizer Otto W. Nuttli St. Louis Univeristy St. Louis, Missouri Editors Paula L. Gori and Walter W. Hays U.S. Geological Survey Reston, Virginia 22092 Open File Report 84-770 Compiled by Carla J. Kitzmiller This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey publication standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the United States Government. Any use of trade names and trademarks in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. Reston, Virginia 1984 Preface The greatest sequence of earthquakes in the history of the United States occurred in the winter of 1811-1812 in New Madrid, Missouri. -

Distribution, Petrology, and Environment of the St. Louis-Ste. Genevieve Transition Zone in Missouri

Scholars' Mine Masters Theses Student Theses and Dissertations 1971 Distribution, petrology, and environment of the St. Louis-Ste. Genevieve transition zone in Missouri Donald Howerton Fielding Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses Part of the Geology Commons Department: Recommended Citation Fielding, Donald Howerton, "Distribution, petrology, and environment of the St. Louis-Ste. Genevieve transition zone in Missouri" (1971). Masters Theses. 6705. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses/6705 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISTRIBUTION, PETROLOGY, AND ENVIRONMENT OF THE ST. LOUIS-STE. GENEVIEVE TRANSITION ZONE IN MISSOURI by DONALD HOWERTON FIELDING, 1938- A THESIS submitted to the faculty of UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI - ROLLA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN GEOLOGY Rolla, Missouri 1971 Approved by (Advisor) 1 ii ABSTRACT In eastern Missouri, southeastern Iowa, and western Illinois e a transition zone, a body of rock consisting of several lithosomes which has a geographic extent measured in scores to hundreds of miles and which lies between a single overlying formation and a single underlying formation and which has lithologic and/or paleontologic properties common to both the overlying and the underlying formations, was found to exist between the St. Louis and the Ste. Genevieve for mations. This transition zone is called the St. Louis-Ste. -

Walden P. Pratt, Editor Prepared in Cooperation with the Missouri

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY METALLIC MINERAL-RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF THE ROLLA I°x2° QUADRANGLE, MISSOURI, AS APPRAISED IN SEPTEMBER 1980 Walden P. Pratt, Editor Prepared in cooperation with the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geology and Land Survey Open-File Report 81-518 1981 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey standards. Tables Page Table 1. Resource potential for Mississippi Valley-type base-metal deposits in Bonneterre Formation and Lamotte Sandstone, September 1980.............................................. 15 2. Estimates of ore "deposits'* in selected areas in the Rolla 1°x2° quadrangle, Missouri.................................. 16 3. Estimated amounts and values of metals in potential ore "deposits" in selected areas of the Rolla I°x2° quadrangle, Missouri.................................................... 19 4. Resource potential for Mississippi Valley-type base-metal and barite deposits in Cambrian and Ordovician formations overlying the Bonneterre Formation, September 1980.......... 22 5. Resource potential for Kiruna-type iron apatite(-copper) deposits, September 1980.................................... 29 6. Spectrographic analyses of hematite and magnetite from the Pilot Knob, Iron Mountain, and Pea Ridge iron deposits...... 31 7. Spectrographic analyses of rocks and minerals from Pilot Knob Mine, Iron County, Missouri............................ 32 8. Spectrographic analyses of ore and gangue minerals from Iron Mountain Mine, Iron County, Missouri................... 33 9* Spectrographic analyses of rocks and minerals from Pea Ridge Iron Mine, Washington County, Missouri............ 34 10. Whole-rock chemical analyses of samples from Avon, Dent Branch, and Bee Fork, Rolla I*x2a quadrangle, Missouri...... 33 11. Spectrographic and chemical analyses of rocks from Dent Branch and Avon diatremes, Rolla I*x2* quadrangle, Missouri................................................... -

U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017

A Product of the Water Availability and Use Science Program Prepared in cooperation with the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Texas at San Antonio and hosted by the Student Geological Society and student chapters of the Association of Petroleum Geologists and the Association of Engineering Geologists U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017 Edited By Eve L. Kuniansky and Lawrence E. Spangler Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5023 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Kuniansky, E.L., and Spangler, L.E., eds., 2017, U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5023, 245 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20175023. -

Paleozoic Geology of the New Madrid Area

NUREG/CR-2909 I ..Paleozoic Geology of the New Madrid Area Prepared by H. R. Schwalb Illinois State Geological Survey Prepared for U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, or any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability of re- sponsibility for any third party's use, or the results of such use, of any information, apparatus, product or protess disclosed in this report, or represents that its use by such third party would not infringe privately owned rights. Availability of Reference Materials Cited in NRC Publications Most documents cited in NRC publications will be available from one of the following sources: 1. The NRC Public Document Room, 1717 H Street, N.W. Washington,'DC 20555 2. The NRC/GPO Sales Program, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Washington, DC 20555 3. The National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161 Although the listing that follows represents the majority of documents cited in NRC publications, it is not intended to be exhaustive. Referenced documents available for inspection and copying for a fee from the NRC Public Docu- ment Room include NRC correspondence and internal NRC memoranda; NRC Office of Inspection and Enforcement bulletins, circulars, information notices, inspection and investigation notices; Licensee Event Reports; vendor reports and correspondence; Commission papers; and applicant and licensee documents and correspondence. The following documents in the NUREG series are available for purchase from the NRC/GPO Sales Program: formal NRC staff and contractor reports, NRC-sponsored conference proceedings, and NRC booklets and brochures. -

Origin of Periclines in the Ozark Plateau, Missouri: a Field and Numerical Modeling

Scholars' Mine Doctoral Dissertations Student Theses and Dissertations Summer 2019 Origin of Periclines in the Ozark Plateau, Missouri: A field and numerical modeling Chao Liu Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/doctoral_dissertations Part of the Geology Commons Department: Geosciences and Geological and Petroleum Engineering Recommended Citation Liu, Chao, "Origin of Periclines in the Ozark Plateau, Missouri: A field and numerical modeling" (2019). Doctoral Dissertations. 2818. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/doctoral_dissertations/2818 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORIGIN OF PERICLINES IN THE OZARK PLATEAU, MISSOURI: A FIELD AND NUMERICAL MODELING by CHAO LIU A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the MISSOURI UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS 2019 Approved by: John Hogan, Advisor Andreas Eckert Jonathan Obrist-Farner Marek Locmelis Klaus Woelk 2019 Chao Liu All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT A series upright sub-horizontal folds in sandstones of the early Ordovician Roubidoux Formation are exposed in road cuts along US Highway 63 in the northern part of the Salem Plateau of central Missouri for over a distance of approximately 10 km. These folds are in marked contrast to the more typical horizontal to sub-horizontal Ordovician strata of the Ozark Plateau.