Recharge Area of Selected Large Springs in the Ozarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fishing on the Eleven Point River

FISHING ON THE ELEVEN POINT RIVER Fishing the Eleven Point National Scenic River is a very popular recreation activity on the Mark Twain National Forest. The river sees a variety of users and is shared by canoes and boats, swimmers, trappers, and anglers. Please use caution and courtesy when encountering another user. Be aware that 25 horsepower is the maximum boat motor size allowed on the Eleven Point River from Thomasville to "the Narrows" at Missouri State Highway 142. Several sections of the river are surrounded by private land. Before walking on the bank, ask the landowners for permission. Many anglers today enjoy the sport of the catch and fight, but release the fish un-harmed. Others enjoy the taste of freshly caught fish. Whatever your age, skill level or desire, you should be aware of fishing rules and regulations, and a little natural history of your game. The Varied Waters The Eleven Point River, because of its variety of water sources, offers fishing for both cold and warm-water fish. Those fishing the waters of the Eleven Point tend to divide the river into three distinctive areas. Different fish live in different parts of the river depending upon the water temperature and available habitat. The upper river, from Thomasville to the Greer Spring Branch, is good for smallmouth bass, longear sunfish, bluegill, goggle-eye (rock bass), suckers, and a few largemouth bass. This area of the river is warmer and its flow decreases during the summer. The river and fish communities change where Greer Spring Branch enters the river. -

Bella Vista Bypass FUTURE INTERSTATE 49 COMES ONE STEP CLOSER to COMPLETION

JULY/AUGUST 2017 A PUBLICATION OF THE ARKANSAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Bella Vista Bypass FUTURE INTERSTATE 49 COMES ONE STEP CLOSER TO COMPLETION MOBILE CONCRETE New Name, VIRTUAL WEIGH LABORATORY New Identity: STATIONS Keep an Eye Comes to Arkansas ARDOT on Commercial Vehicles DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE ARKANSAS STATE HIGHWAY FRONT COVER AND BACK COVER: Bella Vista Bypass COMMISSION State Highway 549 One Family, One Mission, Benton County One Department PUBLISHER DICK TRAMMEL Danny Straessle Chairman N THE MORNING OF TUESDAY, JUNE 27TH, A TRAGIC [email protected] ACCIDENT OCCURRED IN JONESBORO. A commercial vehicle traveling eastbound on I-555 ran off the road and EDITOR Oimpacted multiple columns supporting the Highway 1B overpass. All David Nilles four columns were impacted. Three of the 10 beams had no support [email protected] underneath and began to sag under the weight of the bridge deck. GRAPHIC DESIGNER Paula Cigainero [email protected] The first report was that the overpass was in danger of collapse. I-555, carrying over 33,000 vehicles per day, and Highway 1B, carrying over 10,000 vehicles per day, were closed to traffic. THOMAS B. SCHUECK PHOTOGRAPHER Vice Chairman Our bridge inspectors were on-site quickly, and determined that day that southbound traffic on I-555 under Heavy Bridge Maintenance crews were on the way with timbers to begin shoring up the bridge deck. Early reports Rusty Hubbard the bridge could resume. Northbound I-555 traffic was still to be detoured, and Highway 1B was still closed. [email protected] Our staff from Heavy Bridge Maintenance and District 10 began working around the clock. -

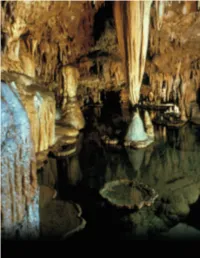

Caves of Missouri

CAVES OF MISSOURI J HARLEN BRETZ Vol. XXXIX, Second Series E P LU M R I U BU N S U 1956 STATE OF MISSOURI Department of Business and Administration Division of GEOLOGICAL SURVEY AND WATER RESOURCES T. R. B, State Geologist Rolla, Missouri vii CONTENT Page Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Acknowledgments 5 Origin of Missouri's caves 6 Cave patterns 13 Solutional features 14 Phreatic solutional features 15 Vadose solutional features 17 Topographic relations of caves 23 Cave "formations" 28 Deposits made in air 30 Deposits made at air-water contact 34 Deposits made under water 36 Rate of growth of cave formations 37 Missouri caves with provision for visitors 39 Alley Spring and Cave 40 Big Spring and Cave 41 Bluff Dwellers' Cave 44 Bridal Cave 49 Cameron Cave 55 Cathedral Cave 62 Cave Spring Onyx Caverns 72 Cherokee Cave 74 Crystal Cave 81 Crystal Caverns 89 Doling City Park Cave 94 Fairy Cave 96 Fantastic Caverns 104 Fisher Cave 111 Hahatonka, caves in the vicinity of 123 River Cave 124 Counterfeiters' Cave 128 Robbers' Cave 128 Island Cave 130 Honey Branch Cave 133 Inca Cave 135 Jacob's Cave 139 Keener Cave 147 Mark Twain Cave 151 Marvel Cave 157 Meramec Caverns 166 Mount Shira Cave 185 Mushroom Cave 189 Old Spanish Cave 191 Onondaga Cave 197 Ozark Caverns 212 Ozark Wonder Cave 217 Pike's Peak Cave 222 Roaring River Spring and Cave 229 Round Spring Cavern 232 Sequiota Spring and Cave 248 viii Table of Contents Smittle Cave 250 Stark Caverns 256 Truitt's Cave 261 Wonder Cave 270 Undeveloped and wild caves of Missouri 275 Barry County 275 Ash Cave -

A Legacy of Neglect: the Ozark National Scenic Riverways

A Legacy of Neglect: The Ozark National Scenic Riverways Susan Flader Missouri’s Current River and its tributary, the Jacks Fork, were the nation’s first fed- erally protected rivers. Congressionally authorized in 1964 as the Ozark National Scenic Riverways (ONSR), they served as a prototype for the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968. But in May 2011 ONSR was identified by American Rivers as one of America’s ten most endangered rivers, owing to a history of inadequate management by the National Park Service (NPS). The spring-fed, bluff-lined Current and Jacks Fork are the preeminent “float streams” in a state where floating, fishing, and camping by johnboat or canoe have long been favorite pastimes (Figure 1). The state’s first Republican governor since Reconstruction, Herbert Hadley, led well-publicized float trips on Current River as early as 1909 in an effort to pro- mote tourism and build support for a state park system. When Missouri acquired its first state parks in 1924, they included Round Spring and Big Spring on the Current River and Alley Spring on the Jacks Fork. The rivers early attracted admirers from afar; Aldo Leopold came from Wisconsin in 1926 to float the Current from Van Buren to Doniphan with his brothers (Leopold 1953; Figure 2), then in 1929 bought a shanty on its bank as a base for annual hunts, years before he acquired his celebrated shack in the sand country of Wisconsin. Like many other rivers that eventually won designation as national wild and scenic rivers, the Current was threatened by proposed hydroelectric dams. -

2005 MO Cave Comm.Pdf

Caves and Karst CAVES AND KARST by William R. Elliott, Missouri Department of Conservation, and David C. Ashley, Missouri Western State College, St. Joseph C A V E S are an important part of the Missouri landscape. Caves are defined as natural openings in the surface of the earth large enough for a person to explore beyond the reach of daylight (Weaver and Johnson 1980). However, this definition does not diminish the importance of inaccessible microcaverns that harbor a myriad of small animal species. Unlike other terrestrial natural communities, animals dominate caves with more than 900 species recorded. Cave communities are closely related to soil and groundwater communities, and these types frequently overlap. However, caves harbor distinctive species and communi- ties not found in microcaverns in the soil and rock. Caves also provide important shelter for many common species needing protection from drought, cold and predators. Missouri caves are solution or collapse features formed in soluble dolomite or lime- stone rocks, although a few are found in sandstone or igneous rocks (Unklesbay and Vineyard 1992). Missouri caves are most numerous in terrain known as karst (figure 30), where the topography is formed by the dissolution of rock and is characterized by surface solution features. These include subterranean drainages, caves, sinkholes, springs, losing streams, dry valleys and hollows, natural bridges, arches and related fea- Figure 30. Karst block diagram (MDC diagram by Mark Raithel) tures (Rea 1992). Missouri is sometimes called “The Cave State.” The Mis- souri Speleological Survey lists about 5,800 known caves in Missouri, based on files maintained cooperatively with the Mis- souri Department of Natural Resources and the Missouri Department of Con- servation. -

Recharge Area of Selected Large Springs in the Ozarks

RECHARGE AREA OF SELECTED LARGE SPRINGS IN THE OZARKS James W. Duley Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Cecil Boswell Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Jerry Prewett Missouri Geological Survey, 111 Fairgrounds Road, Rolla, MO, 65401, USA, [email protected] Abstract parently passing under a gaining segment of the 11 Ongoing work by the Missouri Geological Survey Point River, ultimately emerging more than four kilo- (MGS) is refining the known recharge areas of a number meters to the southeast. This and other findings raise of major springs in the Ozarks. Among the springs be- questions about how hydrology in the study area may ing investigated are: Mammoth Spring (Fulton County, be controlled by deep-seated mechanisms such as basal Arkansas), and the following Missouri springs: Greer faulting and jointing. Research and understanding would Spring (Oregon County), Blue Spring (Ozark County), be improved by 1:24,000 scale geologic mapping and Blue/Morgan Spring Complex (Oregon County), Boze increased geophysical study of the entire area. Mill Spring (Oregon County), two different Big Springs (Carter and Douglas County) and Rainbow/North Fork/ Introduction Hodgson Mill Spring Complex (Ozark County). Pre- In the latter half of the 20th century, the US Forest Ser- viously unpublished findings of the MGS and USGS vice and the National Park Service began serious efforts are also being used to better define recharge areas of to define the recharge areas of some of the largest springs Greer Spring, Big Spring (Carter County), Blue/Morgan in the Ozarks of south central Missouri using water trac- Spring Complex, and the Rainbow/ North Fork/Hodg- ing techniques. -

The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2016–2017 Paddle the Spring-Fed Rivers of Ozark National Forest South of Winona

So Much to Learn: The Ozark National Scenic Riverways and Its Karst Landscape BY QUINTA SCOTT 14 | The Confluence | Fall/Winter 2016–2017 Paddle the spring-fed rivers of Ozark National Forest south of Winona. It has two major tributaries: Scenic Riverways, the Current and its tributary, the Greer Spring and Hurricane Creek, a classic Ozark Jacks Fork. Montauk Spring, Welch Spring, Cave losing stream. Spring, Pulltite Spring, Round Spring, Blue Spring, Use your imagination to understand the and Big Spring are also Current tributaries. A second subterranean drainage of the three rivers. Consider Blue Spring and Alley Spring feed the Jacks Fork. Hurricane Creek, the losing stream with a Put in below at Akers, below Welch Spring, where topographic watershed of 116 square miles. Yes, it’s it is the sixth largest spring in the state and turns the a tributary to the Eleven Point River, but only its last Current from a lazy Ozark stream into a first-class mile carries surface water to the river. The rest seeps float. Don’t forget the Eleven Point, the Wild and into a subterranean system that carries water under Scenic River that flows through Mark Twain National the drainage divide between the Eleven Point and the Current to deliver water to Big Spring. The same holds true for Logan Creek, a losing stream that is a tributary to the Black River. Rain falls on Logan Creek, spills into the subterranean system, crosses under the surface divide between the Black and the Current, and delivers water to Blue Spring. Alley Spring draws from an amazing system of sinkholes and losing streams, including Spring Valley Creek, which becomes a tributary of the Current, once it passes through Round Spring. -

Newsletter of the Arkansas Native Plant Society

CLAYTONIA Newsletter of the Arkansas Native Plant Society Vol. 28 No. 2 An Audience With The Queen Fall/Winter 2008 By Theo Witsell In this issue: Craig “Coondog” Fraiser and I recently spent two long hot days in the Dr. Henry Robison Retires Springfield Plateau Page 3 section of the Ozarks exploring sinkhole ponds Creeping St. John’s Wort and two anonymous Page 4 spring-fed stream gorges*. We had hoped to find some new species Spring Meeting Minutes for Arkansas – Virginia Page 6 sneezeweed (Helenium virginicum), forked aster Field Trip Reports (Eurybia furcata) and tall Page 7 larkspur (Delphinium exaltatum), but struck out Showy lady’s-slipper orchid (Cypripedium reginae). Photo by John Pelton. Bellflower Seed Needed on all counts. But deep Page 10 down, unspoken even, we were both secretly hoping to discover a new population of the showy lady’s-slipper orchid (Cypripedium reginae), far and away the rarest and most seldom-seen lady’s- Fall Meeting Info slipper in Arkansas. It is so rare, and so spectacular, that it often goes by its other name: Page 11 The Queen. Woody Plant CD-ROM Review As we hiked up the rugged canyon of our first stream, we searched likely habitat for Page 13 forked aster (bases of bluffs and limestone ledges with an accumulation of rich, moist soil), but to no avail. But the scenery was spectacular and the water was among the Emerald Ash Borer cleanest and clearest I’ve ever seen in Arkansas. So clear, in fact, that the depth could be deceiving, turning what looked like a knee-deep step into a cold, take-your-breath- Almost to Arkansas away belly-deep plunge. -

Truman State University Press

Truman State University Press front_BSAutumn.indd iii 9/29/08 10:05:32 AM Copyright © 2008 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri USA All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover art: Bryan Culpepper. Used by permission. Pen and ink drawings by Bryan Culpepper; used by permission. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Type: Papyrus digitized data © 2001 Agfa Monotype Corporation and Esselte Letraset Ltd.; a trademark of Esselte Corp. ITC Usherwood © 1990 Adobe Systems Inc.; a registered trademark of International Typeface Corp. Printed by: Edwards Brothers, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stepenoff, Bonnie, 1949– Big spring autumn / Bonnie Stepenoff. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-931112-86-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Ozark Mountains Region—Social life and customs. 2. Ozark Mountains Re- gion—Description and travel. 3. Big Spring (Carter County, Mo.) 4. Carter County (Mo.)—Social life and customs. 5. Carter County (Mo.)—Description and travel. 6. Natural history—Ozark Mountains Region. 7. Natural history—Missouri—Carter County. 8. Stepenoff, Bonnie, 1949—Diaries. I. Title. F472.O9S74 2008 977.8'892043092—dc22 [B] 2008032546 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. The paper in this publication meets or exceeds the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1992. front_BSAutumn.indd iv 9/29/08 8:58:29 AM Contents Drawings by Bryan Culpepper . viii Acknowledgments . ix Introduction . xi The Hills . .1 Part 1: Groundwork . -

U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017

A Product of the Water Availability and Use Science Program Prepared in cooperation with the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Texas at San Antonio and hosted by the Student Geological Society and student chapters of the Association of Petroleum Geologists and the Association of Engineering Geologists U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017 Edited By Eve L. Kuniansky and Lawrence E. Spangler Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5023 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS (1–888–275–8747). For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Kuniansky, E.L., and Spangler, L.E., eds., 2017, U.S. Geological Survey Karst Interest Group Proceedings, San Antonio, Texas, May 16–18, 2017: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2017–5023, 245 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20175023. -

Developing a New Lead District in Missouri: a Conflict Between Maintaining a Mining Heritage and Preserving Ecological Integrity on the Ozark Highland

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1992 Developing a new lead district in Missouri: A conflict between maintaining a mining heritage and preserving ecological integrity on the Ozark Highland Douglas J. Hawes-Davis The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hawes-Davis, Douglas J., "Developing a new lead district in Missouri: A conflict between maintaining a mining heritage and preserving ecological integrity on the Ozark Highland" (1992). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4746. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4746 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY Copying allowed as provided under provisions of the Fair Use Section of the U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW, 1976. Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author’s written consent. MontanaUniversity of DEVELOPING A NEW LEAD DISTRICT IN MISSOURI: A CONFLICT BETWEEN MAINTAINING A MINING HERITAGE AND PRESERVING ECOLOGICAL INTEGRITY ON THE OZARK HIGHLAND by Douglas J. Hawes-Davis B.A. DePauw University, Greencastle, Indiana, 1989 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1992 Approved-by ^ t S. -

A Study of Missouri Springs

Scholars' Mine Professional Degree Theses Student Theses and Dissertations 1935 A study of Missouri springs Harry Cloyd Bolon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/professional_theses Part of the Civil Engineering Commons Department: Recommended Citation Bolon, Harry Cloyd, "A study of Missouri springs" (1935). Professional Degree Theses. 242. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/professional_theses/242 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Degree Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF MISSOURI SPRINGS by liarry C. Bolon A ,T HE SIS submitted to the £aoulty of the SCIDOL OF MINES AND METALLURGY OF TEE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI in partial fulfillment of the work required for tbe DEGREE OF CIVIL ENGINEER Rolla, Mo. 1955 <3Te~.'~_r;fJ /d~~_. Approved b:Y:_--.,.. __ __.-....-__ ~ . Professor of Civil Engineering TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Introduction•••••••••••.••-••.•-. •••••.•..••.••.••• .. • . • • 1 Importance of Springs and Their Worth to Missouri........ 2 Recreation••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ~ •••• 2 Power••••••••••••••••'. •••••••••••••••••••••••• •.• • • • • 5 Watar Supply........................................ 5 Commercial Uses....................................