The Growing Problem of Internet “Link Rot” and Best Practices for Media and Online Publishers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Link ? Rot: URI Citation Durability in 10 Years of Ausweb Proceedings

Link? Rot. URI Citation Durability in 10 Years of AusWeb Proceedings. Link? Rot. URI Citation Durability in 10 Years of AusWeb Proceedings. Baden Hughes [HREF1], Research Fellow, Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering [HREF2] , The University of Melbourne [HREF3], Victoria, 3010, Australia. [email protected] Abstract The AusWeb conference has played a significant role in promoting and advancing research in web technologies in Australia over the last decade. Papers contributed to AusWeb are highly connected to the web in general, to digital libraries and to other conference sites in particular, owing to the publication of proceedings in HTML and full support for hyperlink based referencing. Authors have exploited this medium progressively more effectively, with the vast majority of references for AusWeb papers now being URIs as opposed to more traditional citation forms. The objective of this paper is to examine the reliability of URI citations in 10 years worth of AusWeb proceedings, particularly to determine the durability of such references, and to classify their causes of unavailability. Introduction The AusWeb conference has played a significant role in promoting and advancing research in web technologies in Australia over the last decade. In addition, the AusWeb forum serves as a point of reflection for practitioners engaged in web infrastructure, content and policy development; allowing the distillation of best practice in the management of web services particularly in higher educational institutions in the Australasian region. Papers contributed to AusWeb are highly connected to the web in general, to digital libraries and to other conference sites in particular, owing to the publication of proceedings in HTML and full support for hyperlink based referencing. -

Librarians and Link Rot: a Comparative Analysis with Some Methodological Considerations

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 10-15-2003 Librarians and Link Rot: A Comparative Analysis with Some Methodological Considerations David C. Tyler University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Beth McNeil University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Tyler, David C. and McNeil, Beth, "Librarians and Link Rot: A Comparative Analysis with Some Methodological Considerations" (2003). Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries. 62. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience/62 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. David C. Tyler and Beth McNeil 615 Librarians and Link Rot: A Comparative Analysis with Some Methodological Considerations David C. Tyler and Beth McNeil abstract: The longevity of printed guides to resources on the web is a topic of some concern to all librarians. This paper attempts to determine whether guides created by specialist librarians perform better than randomly assembled lists of resources (assembled solely for the purpose of web studies), commercially created guides (‘Best of the web’-type publications), and guides prepared by specialists in library science and other fields. The paper also attempts to determine whether the characteristics of included web resources have an impact on guides’ longevity. Lastly, the paper addresses methodological issues of concern to this and similar studies. -

An Archaeology of Digital Journalism

ARCHVES MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF rECHNOLOLGY MAY 14 2015 The Missing Links: LIBRARIES An Archaeology of Digital Journalism by Liam Phalen Andrew B.A., Yale University (2008) Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies/Writing in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2015 @ Liam Phalen Andrew, MMXV. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Author .......................................... Department of Comparative Media Studies/Writing Signature redactedM ay 8, 2015 Certified by........................................ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Signature redacted Accepted by ................ Z-/ T.L. Taylor Director of Graduate Studies, Comparative Media Studies 2 The Missing Links: An Archaeology of Digital Journalism by Liam Phalen Andrew Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies/Writing on May 8, 2015, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract As the pace of publishing and the volume of content rapidly increase on the web, citizen journalism and data journalism have threatened the traditional role of institu- tional newsmaking. Legacy publishers, as well as digital-native outlets and aggrega- tors, are beginning to adapt to this new news landscape, in part by drawing newfound value from archival stories and reusing older works. However, this trend's potential remains limited by technical challenges and institutional inertia. -

World Wide Web - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

World Wide Web - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=World_Wide_Web&printabl... World Wide Web From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The World Wide Web , abbreviated as WWW and commonly known as The Web , is a system of interlinked hypertext documents contained on the Internet. With a web browser, one can view web pages that may contain text, images, videos, and other multimedia and navigate between them by using hyperlinks. Using concepts from earlier hypertext systems, British engineer and computer scientist Sir Tim Berners Lee, now the Director of the World Wide Web Consortium, wrote a proposal in March 1989 for what would eventually become the World Wide Web. [1] He was later joined by Belgian computer scientist Robert Cailliau while both were working at CERN in Geneva, Switzerland. In 1990, they proposed using "HyperText [...] to link and access information of various kinds as a web of nodes in which the user can browse at will",[2] and released that web in December. [3] "The World-Wide Web (W3) was developed to be a pool of human knowledge, which would allow collaborators in remote sites to share their ideas and all aspects of a common project." [4] If two projects are independently created, rather than have a central figure make the changes, the two bodies of information could form into one cohesive piece of work. Contents 1 History 2 Function 2.1 What does W3 define? 2.2 Linking 2.3 Ajax updates 2.4 WWW prefix 3 Privacy 4 Security 5 Standards 6 Accessibility 7 Internationalization 8 Statistics 9 Speed issues 10 Caching 11 See also 12 Notes 13 References 14 External links History Main article: History of the World Wide Web In March 1989, Tim BernersLee wrote a proposal [5] that referenced ENQUIRE, a database and 1 of 13 2/7/2010 02:31 PM World Wide Web - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=World_Wide_Web&printabl.. -

Linked Research on the Decentralised Web

Linked Research on the Decentralised Web Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorgelegt von Sarven Capadisli aus Istanbul, Turkey Bonn, 2019-07-29 Angefertigt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Sören Auer 2. Gutachter: Dr. Herbert Van de Sompel Tag der Promotion 2020-03-03 Erscheinungsjahr 2020 Abstract This thesis is about research communication in the context of the Web. I analyse literature which reveals how researchers are making use of Web technologies for knowledge dissemination, as well as how individuals are disempowered by the centralisation of certain systems, such as academic publishing platforms and social media. I share my findings on the feasibility of a decentralised and interoperable information space where researchers can control their identifiers whilst fulfilling the core functions of scientific communication: registration, awareness, certification, and archiving. The contemporary research communication paradigm operates under a diverse set of sociotechnical constraints, which influence how units of research information and personal data are created and exchanged. Economic forces and non-interoperable system designs mean that researcher identifiers and research contributions are largely shaped and controlled by third-party entities; participation requires the use of proprietary systems. From a technical standpoint, this thesis takes a deep look at semantic structure of research artifacts, and how they can be stored, linked and shared in a way that is controlled by individual researchers, or delegated to trusted parties. Further, I find that the ecosystem was lacking a technical Web standard able to fulfill the awareness function of research communication. -

Courting Chaos

SOMETHING ROTTEN IN THE STATE OF LEGAL CITATION: THE LIFE SPAN OF A UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT CITATION CONTAINING AN INTERNET LINK (1996-2010) Raizel Liebler & June Liebert † 15 YALE J.L. & TECH. 273 (2013) ABSTRACT Citations are the cornerstone upon which judicial opinions and law review articles stand. Within this context, citations provide for both authorial verification of the original source material at the moment they are used and the needed information for later readers to find the cited source. The ability to check citations and verify that citations to the original sources are accurate is integral to ensuring accurate characterizations of sources and determining where a researcher received information. However, accurate citations do not always mean that a future researcher will be able to find the exact same information as the original researcher. Citations to disappearing websites cause serious problems for future legal researchers. Our present mode of citing websites in judicial cases, including within U.S. Supreme Court cases, allows such citations to disappear, becoming inaccessible to future scholars. Without significant change, the information in citations within judicial opinions will be known solely from those citations. Citations to the U.S. Supreme Court are especially important of the Court’s position at the top of federal court hierarchy, determining the law of the land, and even influencing the law in international jurisdictions. Unfortunately and disturbingly, the Supreme Court appears to have a vast problem with link rot, the condition of internet links no longer working. We found that number of websites that are no longer working cited to by Supreme Court opinions is alarmingly high, almost one-third (29%). -

Identifiers for the 21St Century

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/117812; this version posted March 20, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 of 27 Identifiers for the 21st century: How to design, provision, and reuse persistent identifiers to maximize utility and impact of life science data 1 2 4 2 1 2 2 3 Julie A McMurry , Nick Juty , Niklas Blomberg , Tony Burdett , Tom Conlin , Nathalie Conte , Mélanie Courtot , John Deck , Michel 5 6 7 8 9 13 Dumontier , Donal K Fellows , Alejandra Gonzalez-Beltran , Philipp Gormanns , Jeffrey Grethe , Janna Hastings , Henning 2 10 11 4 2 12 2 2,13 Hermjakob , Jean-Karim Hériché , Jon C Ison , Rafael C Jimenez , Simon Jupp , John Kunze , Camille Laibe , Nicolas Le Novère , 2 2 2 14 15 16 7 James Malone , Maria Jesus Martin , Johanna R McEntyre , Chris Morris , Juha Muilu , Wolfgang Müller , Philippe Rocca-Serra , 7 18,19 20,21 6 6 22 Susanna-Assunta Sansone , Murat Sariyar , Jacky L Snoep , Natalie J Stanford , Stian Soiland-Reyes , Neil Swainston , Nicole 17 2 1 23 6 17 Washington , Alan R Williams6, Sarala Wimalaratne , Lilly Winfree , Katherine Wolstencroft , Carole Goble , Christopher J Mungall , 1 2 Melissa A Haendel , Helen Parkinson 1. Department of Medical Informatics and Epidemiology and OHSU Library, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, USA. 2. European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, United Kingdom 3. -

Tag by Tag the Elsevier DTD 5 Family of XML Dtds

The Elsevier DTD 5 Family of XML DTDs Tag by Tag The Elsevier DTD 5 Family of XML DTDs Content and Data Architecture, Elsevier B.V. Version 1.9.7.5 March 8, 2021 Correspondence to: Jos Migchielsen Elsevier Radarweg 29 1043 NX Amsterdam Netherlands Email: [email protected] The Tag by Tag was created by Elsevier’s DTD Development & Maintenance Team, the team responsible for development, maintenance and support of the Elsevier DTDs and XML schemas. Former members of the team have contributed to the current documenta- tion. Comments about the DTDs and their documentation, as well as change requests, can be sent to the above-mentioned address. Change requests will be considered for implemen- tation in a future DTD. The Journal Article, Serials Issue, Book and Enhancement Fragment DTDs described in the current documentation are open access material under the CC BY license (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). The Elsevier DTDs, schemas, and a fully clickable PDF file of this documentation are available via http://www.elsevier.com/locate/xml. Elsevier, a Reed Elsevier company, is an integral partner with the scientific, technical and health communities, delivering superior information products and services that foster com- munication, build insights, and enable individual and collective advancement in scientific research and health care. http://www.elsevier.com c 2003–2021 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced and distributed in whole or in part in any medium, physical or electronic, so long as this copy- right notice remains intact and unchanged on all copies. -

A Prospective Analysis of Security Vulnerabilities Within Link Traversal-Based Query Processing

A Prospective Analysis of Security Vulnerabilities within Link Traversal-Based Query Processing Ruben Taelman and Ruben Verborgh IDLab, Department of Electronics and Information Systems, Ghent University – imec, {firstname.lastname}@ugent.be Abstract. The societal and economical consequences surrounding Big Data-driven platforms have increased the call for de- centralized solutions. However, retrieving and querying data in more decentralized environments requires funda- mentally different approaches, whose properties are not yet well understood. Link-Traversal-based Query Process- ing (LTQP) is a technique for querying over decentralized data networks, in which a client-side query engine dis- covers data by traversing links between documents. Since decentralized environments are potentially unsafe due to their non-centrally controlled nature, there is a need for client-side LTQP query engines to be resistant against security threats aimed at the query engine’s host machine or the query initiator’s personal data. As such, we have performed an analysis of potential security vulnerabilities of LTQP. This article provides an overview of security threats in related domains, which are used as inspiration for the identification of 10 LTQP security threats. Each threat is explained, together with an example, and one or more avenues for mitigations are proposed. We conclude with several concrete recommendations for LTQP query engine developers and data publishers as a first step to mitigate some of these issues. With this work, we start filling the unknowns for enabling querying over decentral- ized environments. Aside from future work on security, wider research is needed to uncover missing building blocks for enabling true decentralization. 1. Introduction can contain any number of documents, where its own- er can determine who or what can access what parts of Contrary to the Web’s initial design as a decentral- this data. -

Of Key Terms

1 Index of Key Terms Symbols active audience 2977 2.5 Generation Wireless Service (2.5G) 390 database 2881 learning 372 server page (ASP) 144, 517, 1406, 2474 A server page (ASP) scripting 684 A/VE 1897 server page (ASP) aggregator 145 absorptive capacity 1044, 2518 X control 2312 abstract activities 2006, 3089 dimension 2820 activity diagram 329 windows toolkit (AWT) 1668 actor 41, 45, 2006, 2953 academic administration 1707 actor-network theory (ANT) 41, 46, 2011 acceptable use policy (AUP) 2028 actual level of awareness 572 access actuary 172 board standards 884 adaptability 97 control list (ACL) 1523 adaptive accessibility 884, 1819, 1287 algorithm 2595 data quality 1921 feedback 2329 accessible 3083 filter 2595 technology 2919 learning 3064 Web design 884 adaptor 2418 accommodations 2212 added value 2307 accountability 1418 ADDIE 1347 accountable identification 994 adding value 2752 accounting performance measures 176 addressable anit 869 accreditation 901 ADISSA 1115 acculturation 2850 administrative accuracy 2109 and institutional support 1000 ACF 2192 tasks 2792 ACID properties 589, 938 adoption 1188, 2518, 2966 ACS 2984 advanced action 572, 2881 information technology structure 1995 research 297 Internet applications 863 theory 122 advisory agents 80 actionable information 1910 affect-based trust 1869 action-oriented formal specification language affective 1210 complexity 1029 activation function 2098 computing 1056, 1185 activation-emotion space 1185 or relationship conflict 2915 Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc., distributing -

Capture All the Urls First Steps in Web Archiving

Practice Capture All the URLs First Steps in Web Archiving Alexis Antracoli, Steven Duckworth, Judith Silva, & Kristen Yarmey Alexis Antracoli is Records Management Archivist at Drexel Libraries, [email protected] Steven Duckworth served as Records Management Intern at Drexel University and is now an Archivist with the National Park Service, [email protected] Judith Silva is the Fine & Performing Arts Librarian and Archivist at Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Kristen Yarmey is an Associate Professor and Digital Services Librarian at the University of Scranton Weinberg Memorial Library, [email protected] As higher education embraces new technologies, university activities—including teaching, learning, and research—increasingly take place on university websites, on university- related social media pages, and elsewhere on the open Web. Despite perceptions that “once it’s on the Web, it’s there forever,” this dynamic digital content is highly vulnerable to degradation and loss. In order to preserve and provide enduring access to this complex body of university records, archivists and librarians must rise to the challenge of Web archiving. As digital archivists at our respective institutions, the authors introduce the concept of Web archiving and articulate its importance in higher education. We provide our institutions’ rationale for selecting subscription service Archive-It as a preservation tool, outline the progress of our institutional Web archiving initiatives, and share lessons learned, from unexpected stumbling blocks to strategies for raising funds and support from campus stakeholders. Vol. 2, No. 2 (Fall 2014) DOI 10.5195/palrap.2014.67 155 New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. -

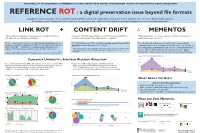

REFERENCE ROT : a Digital Preservation Issue Beyond file Formats

ARCHIVABILITY OF DOCUMENTS IS EMERGING AS A BEST PRACTICE IN DIGITAL PRESERVATION. WHAT'S IN YOUR INSTITUTIONAL REPOSITORY? REFERENCE ROT : a digital preservation issue beyond file formats Mandated electronic deposit of theses and dissertations (ETDs) carries with it digital preservation concerns for librarians in a new role as defacto digital publisher. As scholarly content vanishes due to the nature of the ephemeral web, what's next for digital-born documents deposited in our institutional repositories? LINK ROT + CONTENT DRIFT ••• MEMENTOS Links pointing to webpages & resources are no longer available at Links work, but URL page content has evolved over time and differs, Digital snapshots, i.e., screen captures, which are preserved in URL address, e.g., 404-page not found. sometimes dramatically, from what was there originally. publicly accessible archives. "All three corpora show a moderate, yet alarming, link rot ratio for references "We find that for over 75% of references the content has drifted The international archiving community has been periodically made in recent articles, published in 2012: 13% for arXiv, 22% for Elsevier, away from what it was when referenced." crawling websites and saving mementos for years. An example of and 14% for PMC ... Going back to the earliest publication year in our such incidental archiving is Internet Archive's Wayback Machine. corpora, 1997, the ratios become 34%, 66%, and 80%, respectively." Jones, S. M., Van de Sompel, H., Shankar, H., Klein, M., Tobin, R., & Grover, C. (2016). Scholarly Context Adrift: Three out of Four URI References Lead to Changed Content. PloS one, 11(12), Even if libraries have undertaken no actions to insure digital Klein, M., Van de Sompel, H., Sanderson, R., Shankar, H., Balakireva, L., Zhou, K., & Tobin, R.