Alyssagabriele.Finalthesis2018 (5).Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

20-A Richard Diebenkorn, Cityscape I, 1963

RICHARD DIEBENKORN [1922–1993] 20a Cityscape I, 1963 Although often derided by those who embraced the native ten- no human figure in this painting. But like it, Cityscape I compels dency toward realism, abstract painting was avidly pursued by us to think about man’s effect on the natural world. Diebenkorn artists after World War II. In the hands of talented painters such leaves us with an impression of a landscape that has been as Jackson Pollack, Robert Motherwell, and Richard Diebenkorn, civilized — but only in part. abstract art displayed a robust energy and creative dynamism Cityscape I’s large canvas has a composition organized by geo- that was equal to America’s emergence as the new major metric planes of colored rectangles and stripes. Colorful, boxy player on the international stage. Unlike the art produced under houses run along a strip of road that divides the two sides of the fascist or communist regimes, which tended to be ideological painting: a man-made environment to the left, and open, pre- and narrowly didactic, abstract art focused on art itself and the sumably undeveloped, land to the right. This road, which travels pleasure of its creation. Richard Diebenkorn was a painter who almost from the bottom of the picture to the top, should allow moved from abstraction to figurative painting and then back the viewer to scan the painting quickly, but Diebenkorn has used again. If his work has any theme it is the light and atmosphere some artistic devices to make the journey a reflective one. of the West Coast. -

In Goede Orde Veranderlijk Geordineerd

doi: 10.2143/GBI.37.0.3017262 IN GOEDE ORDE VERANDERLIJK GEORDINEERD SCHRIFTELIJKE BRONNEN OVER (MARMER)STENEN VLOEREN IN HET NEDERLANDSE INTERIEUR VAN DE 17DE EN 18DE EEUW INGER GROENEVELD Historische natuurstenen vloeren hebben iets magisch in Die visie ten aanzien van het voorkomen van natuurstenen een land dat van nature nauwelijks harde grond onder de vloeren in het Nederlandse interieur van de 17de eeuw is voeten kent.1 Ze zijn onlosmakelijk verbonden met onze overgenomen in verschillende binnen- en buitenlandse rijke handelsgeschiedenis: de binnenvaart over de Maas en kunsthistorische studies.5 de Schelde en de kleine vaart tussen Zweden en de Middel- landse Zee. De gepolijste, barstloze en regelmatig gelegde Na 2001 kwam er ten aanzien van de 18de eeuw een natuurstenen vloer – alsook de smetteloos geschuurde, zekere nuancering. Zo maakte het promotieonderzoek van knoestloze grenen vloer – is van oudsher verbonden met dr. Johan de Haan naar het Groninger interieur (2005) de legendarische properheid en deugdzaamheid van de – tussen de regels door – een aanzet tot (regionale) bij- Hollandse huisvrouw. De vloer werd in de schilderkunst stelling van het beeld dat in die eeuw enkel witmarmeren verbeeld als podium van huiselijke harmonie, met de bezem vloeren de toon zetten.6 (afb. 1) als deurwachter in de hoek. Sinds de eerste studies naar het Nederlandse historische interieur is het beeld van de Bovengenoemde studies ten spijt is er nog nooit afzonder- natuurstenen vloer in de 17de en 18de eeuw vooral bepaald lijk interieurhistorisch onderzoek gedaan naar de natuurste- geweest door de stilistische veronderstelling ‘patroonvloer, nen stenen vloer. Het ontbrak zodoende aan een op harde dus 17de eeuw’ en ‘witte marmeren vloer, dus 18de eeuw’. -

The Meaning and Significance of 'Water' in the Antwerp Cityscapes

The meaning and significance of ‘water’ in the Antwerp cityscapes (c. 1550-1650 AD) Julia Dijkstra1 Scholars have often described the sixteenth century as This essay starts with a short history of the rise of the ‘golden age’ of Antwerp. From the last decades of the cityscapes in the fine arts. It will show the emergence fifteenth century onwards, Antwerp became one of the of maritime landscape as an independent motif in the leading cities in Europe in terms of wealth and cultural sixteenth century. Set against this theoretical framework, activity, comparable to Florence, Rome and Venice. The a selection of Antwerp cityscapes will be discussed. Both rising importance of the Antwerp harbour made the city prints and paintings will be analysed according to view- a major centre of trade. Foreign tradesmen played an es- point, the ratio of water, sky and city elements in the sential role in the rise of Antwerp as metropolis (Van der picture plane, type of ships and other significant mari- Stock, 1993: 16). This period of great prosperity, however, time details. The primary aim is to see if and how the came to a sudden end with the commencement of the po- cityscape of Antwerp changed in the sixteenth and sev- litical and economic turmoil caused by the Eighty Years’ enteenth century, in particular between 1550 and 1650. War (1568 – 1648). In 1585, the Fall of Antwerp even led The case studies represent Antwerp cityscapes from dif- to the so-called ‘blocking’ of the Scheldt, the most im- ferent periods within this time frame, in order to examine portant route from Antwerp to the sea (Groenveld, 2008: whether a certain development can be determined. -

11 Corporate Governance

144 11 Corporate governance MARJOLEIN ’T HART The Bank of Amsterdam´s commissioners: a strong network For almost 200 years, up to the 1780s, the Bank of Amsterdam operated to the great satisfaction of the mercantile elite. Its ability to earn and retain the confidence of the financial and commercial elite was highly dependent on its directors, the commissioners. An analysis of their backgrounds shows that many of them once held senior posts in the city council, although the number of political heavyweights decreased over time. The commissioners also took office at an increasingly younger age. After the first 50 years of the bank, they began to stay on in office longer, indicating a certain degree of professionalisation. The commissioners had excellent connections with stock exchange circles. The majority of them were merchants or bankers themselves, and they almost all had accounts with the bank. As a result, the commissioners formed a very strong network linking the city with the mercantile community. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 145 François Beeldsnijder, 1688-1765, iron merchant and commissioner of the Bank of Amsterdam for 15 years Jan Baptista Slicher; Amsterdam, 1689-1766, burgomaster, merchant, VOC director and commissioner of the Bank of Amsterdam for 16 years A REVOLUTIONARY PROPOSAL This was the first time that the commissioners of the On 6 June 1797, in the wake of revolutionary upheaval, Bank of Amsterdam had come in for such sharp criticism. Amsterdam’s city council, which had itself undergone Of course, some aspects of the bank had been commented radical change, decided on a revolutionary put forward on before. -

Rare Cityscape by Jacob Van Ruisdael of Budapest on Loan at the Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age Exhibition

Press release Amsterdam Museum 25 February 2015 Rare cityscape by Jacob van Ruisdael of Budapest on loan at the Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age exhibition For a period of one year commencing on the 27th of February, the Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age exhibition will be enriched with a rare cityscape by Jacob van Ruisdael (1628-1682) from the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum (Museum of Fine Arts) in Budapest: View of the Binnenamstel in Amsterdam. The canvas shows Amsterdam in approximately 1655, shortly before Amstelhof was built, the property in which the Hermitage Amsterdam is currently situated. The painting is now back in the city where it was created, for the first time since 1800. With this temporary addition, visitors to the Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age can experience how the city looked around 350 years ago seen from the place where they will end up after their visit. There are only a few known cityscapes by Jacob van Ruisdael. Usually, with this perhaps most "Dutch" landscape painter, the city would at best figure in the background, as in his views of Haarlem, Alkmaar, Egmond and Bentheim. Only in Amsterdam, where he is documented as being a resident from 1657, did he stray a few times within the city walls. It has only recently been established properly and precisely which spot in which year is depicted on the painting. Curator of paintings, sketches and prints Norbert Middelkoop from the Amsterdam Museum described it last year in an entry for the catalogue on the occasion of the Rembrandt and the Dutch Golden Age exhibition in the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum in Budapest. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

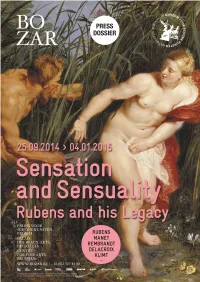

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Walk Among Teyler and Hals

Verspronckweg Schotersingel Kloppersingel Staten Bolwerk Kennemerplein Rozenstraat Prinsen Bolwerk Kenaustraat Stationsplein singel Parkeergarage Stationsplein Garenkookerskade Kenaupark Kinderhuis Parklaan Parklaan Parklaan Kruisweg Jansweg Parklaan Hooimarkt Spaarne Nieuwe Gracht Nieuwe Gracht Nassaustraat Zijlweg Kinderhuissingel Kinderhuisvest Ridderstraat BakenessergrachtBakenessergracht Koudenhorn Kruisstraat Molen De Adriaan Grote or St. Bavokerk (20, St Bavo’s Church) was built in Gothic Walk left of the town hall into Koningstraat. Halfway down this street, on your Jansstraat 22 Nassaulaan style in the spot where a smaller church, which was largely destroyed in right, you can see the former school for Catholic girls, ‘Inrichting voor Onderwijs Route 1 - Starting point: Frans Hals Museum Route map WALK AMONG a fire in the 14th century, once stood. St Bavo is the patron saint of the aan Katholieke Meisjes’ and then on your left at No. 37, the asymmetrically shaped Zijlstraat Papentorenvest Route 2 - Starting point: Teylers Museum Smedestraat TEYLER AND HALS Kennemerland region. In 1479, the building was rebuilt as a collegiate church. former bakery (24) in Berlage style (1900). Decorative Jugendstil carvings by Brouwersvaart The remarkable thing about this church is that it was built without piles in G. Veldheer embellish both sides of the freestone façade frame. The figure of a Bakenessergracht the ground. Grote or St. Bavokerk is sometimes also referred to as ‘Jan met baker is depicted in the keystone above the shop window. Gedempte Oude Gracht Zijlstraat Raaks 15 de hoge schouders’ (high-shouldered John) because the tower is rather small Barteljorisstraat compared to the rest of the building. The church houses the tombs of Frans At the end of Koningstraat, cross Gedempte Oude Gracht and continue straight on Grote 16 Parkeer- Drossestraat 23 19 Hals, Pieter Teyler Van der Hulst and Pieter Jansz. -

3D Reconstructions As Research Hubs: Geospatial Interfaces for Real-Time Data Exploration of Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam Domestic Interiors

Open Archaeology 2021; 7: 314–336 Research Article Hugo Huurdeman*, Chiara Piccoli 3D Reconstructions as Research Hubs: Geospatial Interfaces for Real-Time Data Exploration of Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam Domestic Interiors https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2020-0142 received December 7, 2020; accepted April 23, 2021 Abstract: This paper presents our ongoing work in the Virtual Interiors project, which aims to develop 3D reconstructions as geospatial interfaces to structure and explore historical data of seventeenth-century Amsterdam. We take the reconstruction of the entrance hall of the house of the patrician Pieter de Graeff (1638–1707) as our case study and use it to illustrate the iterative process of knowledge creation, sharing, and discovery that unfolds while creating, exploring and experiencing the 3D models in a prototype research environment. During this work, an interdisciplinary dataset was collected, various metadata and paradata were created to document both the sources and the reasoning process, and rich contextual links were added. These data were used as the basis for creating a user interface for an online research environment, taking design principles and previous user studies into account. Knowledge is shared by visualizing the 3D reconstructions along with the related complexities and uncertainties, while the integra- tion of various underlying data and Linked Data makes it possible to discover contextual knowledge by exploring associated resources. Moreover, we outline how users of the research environment can add annotations and rearrange objects in the scene, facilitating further knowledge discovery and creation. Keywords: virtual reconstructions, digital humanities, interface design, human–computer interaction, domestic architecture 1 Introduction In this paper, we explore the use of 3D reconstructions¹ as heuristic tools in the research process. -

LS Landscape/Seascape/Cityscape SL Still Life PO Portrait FL Floral

Photography Show - Category Code Definitions LS Landscape/Seascape/Cityscape Landscape photography shows spaces within the world, sometimes vast and unending, but other times microscopic. Landscape photographs typically capture the presence of nature but can also focus on man-made features or disturbances of landscapes. A seascape is a photograph that depicts the sea, or an example of marine art. The word has also come to mean a view of the sea itself, and when applied in geographical context, refers to locations possessing a good view of the sea. A cityscape is a city viewed as a scene; an artistic representation of a city; an urban environment. A cityscape (urban landscape) is a photograph of the physical aspects of a city or urban area. It is the urban equivalent of a landscape. Townscape is roughly synonymous with cityscape, and it implies the same difference in size and density implicit in the difference between the words city and town. SL Still Life Still life photography is the depiction of inanimate subject matter, most typically a small grouping of objects. Still life photography, more so than other types of photography, such as landscape or portraiture, gives the photographer more leeway in the arrangement of design elements within a composition. Still life photography is a demanding art, one in which the photographers are expected to be able to form their work with a refined sense of lighting, coupled with compositional skills. The still life photographer makes pictures rather than takes them. PO Portrait Portrait photography or portraiture in photography is a photograph of a person or group of people that captures the personality of the subject by using effective lighting, backdrops, and poses. -

Landscape Photography: Types and Styles

Landscape Photography: Types and Styles Scenery is the subject of a landscape image. Usually people or animals are not shown in a landscape photograph. Similarly, city skylines and oceans are generally not shown. To a purist these would be called cityscape and seascape respectively. Landscape photographs are supposed to be just that; landscapes. There are three major styles of landscape photography 1. Representational (also known as straight descriptive style) 2. Impressionistic 3. Abstract Representational: Representational landscapes are the most natural and realistic out of all the styles of landscape photography. They approach landscape photography with a what you see is what you get mentality. No props or artificial components are added. However special attention is paid to the framing, lighting and composition of the image. See Joel Sternfield Impressionistic: An impressionistic landscape carries with it a vague or elusive sense of reality. These photographs will make the landscape seem more unreal. The viewer is giving the impression of a landscape rather than the true representation of one. See Wynn Bullock Abstract: Abstract landscape photographs use components of the scenery as graphic components. With abstract landscape photography design is more important than a realistic representation of what is seen. The photographer may place emphasis on something which seems counterintuitive to place emphasis on. They may make use of silhouettes or other lighting techniques to highlight shape, They may focus in on an area within the landscape itself. See Edward Weston Landscape and Architecture Photography. Natural Landscape: a natural landscape is a landscape that is unaffected by human activity, The natural landscape is a place under the current control of natural forces and free of the control of people for an extended period of time.