And Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mutton Or Chicken Akhni

MUTTON OR CHICKEN AKHNI MUTTON OR CHICKEN AKHNI In a pot braise a large onion with oil (if using mutton) if chicken little oil n ghee till pale pink. Add in 1 teaspoon whole jeera seeds 4 whole black peppercorns 4 whole elachi pods 3 pieces cinnamon sticks 4 whole cloves 3 sliced green chillies Braise till golden brown. Then add in your meat or chicken. Add: 1 tablespoon of ginger and garlic paste 1 ½ teaspoon salt ±1 ½ teaspoon turmeric 1 teaspoon of red chilies paste STIR WELL Braise for a few minutes. Add some water and let cook till meat is tender. When meat is tender and water is almost dry add the other masalas: ± 2 tablespoons chili powder 2 teaspoons dhana /jeero powder 1 teaspoon crushed chillie powder some peas Braise nicely for few minutes then add in 1 grated tomato. Cook a few minutes. add 2 tbsp plain yogurt Add 6 cups boiling water and add in potatoes about 5 cut in pieces. Let boil for a few min so potatoes start getting soft. Lower heat a bit. Add 3 cups pre soaked basmati rice and add to pot. Add some salt for taste. Add in some chopped dhania and mint and about half teaspoon garam masala powder. Let boil for a few minutes till rice starts cooking. Stir also so well so that rice doesn’t stick to the bottom. When rice is boiling nicely and water is almost drying but there must be some water then put in oven and steam for about 30 to 40 minutes at 180°C. -

Restaurant Menu

Authentic Indian Cuisine STARTERS - MIXED STARTERS - SEAFOOD Mixed Kebab ......................................... £4.95 Prawn Cocktail ..................................... £3.95 Vegetable Platter (for two) ........................ £7.95 Prawn Puree .......................................... £4.95 Tikka Platter (for two) ............................... £8.95 Deep fried unleavened bread with prawn stuffing Sword Fish Tikka ................................... £5.95 STARTERS - VEGETABLE Stuffed Prawn Pepper ........................... £5.95 Onion Bhaji Deep fried spiced onion cutlets ......... £3.50 King Prawn Puree .................................. £5.95 Vegetable Samosa Deep fried pasties ........... £3.50 Deep fried unleavened bread with king prawn stuffing Aloo Chat Pieces of potato cooked in sour sauce ..... £3.50 King Prawn Garlic ................................. £5.95 Chilli Mushrooms .................................. £3.50 King prawn in garlic and butter Garlic Mushrooms ................................ £3.50 King Prawn Butterfly ............................. £5.95 Paneer Tikka ......................................... £3.75 King Prawns Shashlick BAZZAR special........ £5.95 Indian cheese marinated with spices and herbs Chana Paneer ........................................ £4.50 TANDOORI SPECIALITIES Channa puree ........................................ £4.50 These dishes are marinated with spices and then grilled in a special tandoor and served with salad Paneer Shashlick .................................. £4.50 Indian cheese -

An Historical Analysis of Awankaru Sounds with a New'perspective

An historical analysis of Awankaru Sounds with a new'perspective Thorough investigation into Indo-Aryan, Arabic-Persian and European elements. New theories, bold assertions, interesting suggestions. + H/1RDEV BAHRI Publishers BHARA*IS?RESS PRAKASHAN, DARBHANOA ROAD, ALLAHABAD—2. B^ffg |MM } (INDIA). $ ol e^ Distributors ¥ lLOKBHAifATif 15A—Mahatma Gandhi | margj I'MM 1_ J I Allahabad—1 Rsl^O. Prof Dr. H Pri D"^namSrnghSbab V.G *05. Sector 16 SikhiscD t-'tattdi<tarh \ ] la! [With special reference to Awankari] HARDEV BAHRI M.A., M.O.L., PH.D., D.LITT., SHASTRI * r ALLAHABAD EHflRflTI PRESS PUBLICATIONS DARBHANGA ROAD. Copyright, 1962 ^ Lahndi Phonology [Part II of the Thesis approved by the Punjab University, Lahore*. for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 1944]' Sole Distributors: LOKBHARATI 15-A, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, Allahabad—1. PRINTED IN INDIA BY THE BHARATI PRESS, DARBHANGA ROAD 'ALLAHABAD—2, i CONTENTS CONTENTS A WORD • iv CHART OF PHONETIC SYMBOLS AND PRONUNCIATION LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED vii INTRODUCTION ? ' ;" ix PHONOLOGY OF I-A. ELEMENT I* Preservations * ' II. Extinctions 13 III. Modifications IV# General^ Problems in Modifications 15$ V. Phonetic Semantic Modifications VI. Extensions (including History of Final Sounds) • VII. Onomatopoetic Formations 101 VIII. Agents of Change 11? '.]"•' IX. Possibilities (including Obscurities & Deshis of the Dialect) 14a : PHONOLOGY OF FOREIGN ELEMENT i X. Persian Element 155 XI. English Element 193 BIBLIOGRAPHY ' 209 INDEX OF LAHNDI WORDS AND SOUNDS 212 INDEX OF SOURCE SOUNDS 234 > INDEX OF SUBJECTS 237 # A WORD The present work is a part of the thesis submitted to the Punjab University, Lahore, in 1941 ^and approved for the degree -of Doctor of Philosophy in the Oriental Faculty. -

BANGLADESH: COUNTRY REPORT to the FAO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE on PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Leipzig 1996)

BANGLADESH: COUNTRY REPORT TO THE FAO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE ON PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Leipzig 1996) Prepared by: M. Sujayef Ullah Chowdhury Dhaka, April 1995 BANGLADESH country report 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the FAO International Technical Conference on Plant Genetic Resources, Leipzig, Germany, 17-23 June 1996. The Report is being made available by FAO as requested by the International Technical Conference. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of the material and maps in this document do not imply the expression of any option whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. BANGLADESH country report 3 Table of contents FOREWORD 5 PREFACE 7 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO BANGLADESH AND ITS AGRICULTURE 10 CHAPTER 2 INDIGENOUS PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES 19 2.1 FOREST GENETIC RESOURCES 19 2.2 MEDICINAL PLANTS 22 2.3 OTHER WILD SPECIES AND WILD RELATIVES OF CROP PLANTS 22 2.4 LANDRACES (“FARMERS’ VARIETIES”) AND OLD CULTIVARS 22 CHAPTER 3 NATIONAL CONSERVATION ACTIVITIES 29 3.1 IN SITU CONSERVATION ACTIVITIES 30 3.2 EX SITU COLLECTIONS -

NHC Menu February 20

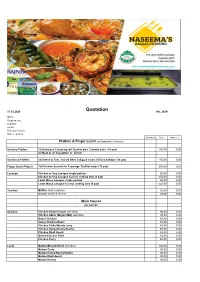

03 02 2020 Quotation No. 2020- Name Request no. Contact email Delivery Venue Date required Quantity Price Amount Platters & Finger Lunch (in Disposable Container) Savoury Platters 12xSamoosa 12xspring roll 12xmini pies 12xmeat balls (10 pax) 450,00 0,00 All Meat or all Veg option or all mix Sandwich Platters 3xCheese & Tom, 3xCold Beef, 3xEgg & salad, 3xTuna & Mayo (10 pax) 450,00 0,00 Finger lunch Platters 12xChicken drumsticks 12xwings 12xfillet strips (10 pax) 550,00 0,00 Lasange Chicken or Veg Lasagne single portion 60,00 0,00 Chicken or Veg Lasagne 1/2 rect chafing dish (9 pax) 450,00 0,00 Lamb Mince Lasagne single portion 65,00 0,00 Lamb Mince Lasagne 1/2 rect chafing dish (9 pax) 520,00 0,00 Tea time Muffins butter and jam 25,00 0,00 Scones butter & cheese 25,00 0,00 Main Course per person Chicken Chicken Biryani (layer) with dhay 80,00 0,00 Chicken Akhni (Biryani Mix) with dhay 70,00 0,00 Butter Chicken 65,00 0,00 Saucy Chicken Roast 65,00 0,00 Chicken Tikka Masala curry 65,00 0,00 Chicken Kaliya/Korma/Kariha 65,00 0,00 Chicken Dhall Gosht 65,00 0,00 Grilled Chicken Fillet 65,00 0,00 Chicken Curry 65,00 0,00 Lamb Mutton Biryani/Akhni with dhay 100,00 0,00 Mutton Curry 90,00 0,00 Mutton Kaliya/Korma/Kariha 90,00 0,00 Mutton Dhall Gosht 90,00 0,00 Mutton Keema 90,00 0,00 Beef Grilled Masala Steak 90,00 0,00 Grilled T-Bone 90,00 0,00 Saucy Pepper Steak 90,00 0,00 Salt & Pepper Grilled Steak 90,00 0,00 Gravy Steak 90,00 0,00 Gravy T-Bone 90,00 0,00 Beef Keema 90,00 0,00 Beef Korma/Kariha/Kaliya 90,00 0,00 Vegetable Vegetable Biryani/Akhni -

BIRYANI DISHES ENGLISH DISHES Biryani, Traditionally Known As Akhni (In Bangladesh), Is an Aromatic Pilau-Style Dish with Meat, Vegetables Or Seafood

BIRYANI DISHES ENGLISH DISHES Biryani, traditionally known as Akhni (in Bangladesh), is an aromatic pilau-style dish with meat, vegetables or seafood. Sirloin Steak ................................................................... 14.95 Originating from the Mughal cuisine of the 16th-19th centuries, it was a Served with fried onions and mushrooms, festive dish, costly to prepare and eaten mainly in the royal courts. hand cut chunky chips and salad. Chicken / Vegetable ........................................................9.95 Fish Bites and Chips......................................... 5.95 8.95 Chicken Tikka / Lamb...................................................10.95 Omelette and Chips.......................................... 5.95 8.95 A choice of chicken, mushroom, cheese or vegetable Prawn ......................................................................................10.95 served with chips and salad. King Prawn........................................................................... 13.95 Chicken Nuggets and Chips ........................ 5.95 8.95 The Spiced Mango Royal Mixed Biryani............. 14.95 Scampi and Chips.............................................. 5.95 8.95 SUNDRIES VEGETARIAN DISHES Steamed Basmati Rice .................................................... 2.25 Most of our Vegetarian dishes can be prepared to strict Vegan standards. Please inform a member of our waiting sta. Pilau Rice.................................................................................2.40 Coconut Rice........................................................................ -

Kebab Pavillion Menu

K EBAB PAVILLION MENU VEGETARIAN KEBABS S UBZ S HAMMI K EBAB MINCED ASSORTED VEGETABLES MARINATED WITH SPICES, HERBS, YOGHURT AND PAN GRILLED P ANEER T IKKA KEBAB OF FRESH COTTAGE CHEESE, MARINATED IN A BATTER OF CREAM, GRAM FLOUR RED CHILLIES ,SKEWERED AND GRILLED IN THE “TRADITIONAL” OVEN T ANDOORI P HOOL WHOLE CAULIFLOWER SEASONED WITH YELLOW CHILI, CHAAT MASALA, LEMON JUICE AND GINGER PASTE, COATED WITH AN “AJWAIN” FLAVORED BATTER OF GRAM FLOUR, FRIED SKEWERED AND CHAR GRILLED T ANDOORI A LOO SCOOPED POTATOES, STUFFED WITH POTATO HASH, RAISINS, CASHEW NUTS, MIXED WITH GREEN CHILIES, GREEN CORIANDER, SKEWERED AND ROASTED OVER CHARCOAL FIRE E LLAA ’ S CHEF SPECIAL VEGET ARIAN KEBABS K EBAB P LATTER M E A L 4 DELICIOUS KEBABS SERVED IN A PLATTER WITH DAL MAKHNI, LASOONI DAL, BREAD BASKET, BIRYANI AND DESSERT P HALDARI CHAT SEASONAL FRUITS MARINATED WITH A SPICY MIXTURE OF CHAAT MASALA, YELLOW CHILIES, “GARAM MASALA”, BLACK CUMIN AND LEMON JUICE SKEWERED AND GRILLED IN THE “TANDOOR” A LOO SHEEKAMPURI WELL SEASONED POTATO, STUFFED WITH CHOP ONIONS, CHEESE, GREEN CHILIES SEASONED WITH CUMIN CORIANDER DEEP FRIED TILL GOLDEN BROWN. SERVED WITH MINT CHUTNEY HARA BARA KEBAB SEASONAL VEGETABLE WITH WHOLE SOME OF GREEN PEAS SEASONED WITH WHOLE GRAMA MASALA MINCED, WEDGED WITH CASHEW NUT AND GOLDEN FRIED A JWAIN P ANEER T IKKA KEBAB OF FRESH COTTAGE CHEESE, MARINATED IN A BATTER OF CREAM, GRAM FLOUR, “AJWAIN” AND YELLOW CHILI SKEWERED AND GRILLED IN THE “TRADITIONAL” OVEN NON VEGETARIAN KABABS T ANDOORI J HINGA JUMBO PRAWNS MARINATED IN AN “AJWAIN” FLAVORED MIXTURE OF YOGHURT, RED CHILIES, TURMERIC AND SEASONED WITH GARAM MASALA SKEWERED AND ROASTED OVER CHARCOAL FIRE. -

Veggie Salad Chicken Tenderloin CHAR GRILLED LAMB CHOPS

Menu Veggie Salad Tomato Balsamic Salad INR 175 Cherry Tossed with italian Balsamic, crushed wild garlic and freshly Squeezed lemon juice. Full of Vitamin C and Potassium Yellow Spring's Nature INR 175 Red and yellow Papers, parsley, Onions tossed in a ginger and balsamic dressing Naomi's Spinach n Walnut salad INR 175 Top models have top diet secrets that they rarely unveil. Enjoy this Nutrious sald with fresh Spinach tossed with chef Inam's special vinaigrette, tossed with roasted Walnuts. Loir Valley Salad INR 175 Diced Cucumber, Tomatoes, Pineapple, Celery, Fresh rosemary with wild lemon dressing Chicken Chargrilled caper Balsamic Chicken Steak salad INR 225 Capper Balsamic Grilled chicken tossed with greens Honey pepper Chicken Salad INR 225 Chicken tossed with crushed pepper and honey, Chargrill, Mix with lettuce and herbs New England Chicken Salad INR 225 Sundry Herb Grilled chicken tossed with greens Tenderloin Lemon teriyaki Steak Salad INR 275 Chargrilled Steak Tossed with fresh lemon n teriyaki mixed with greens peri peri steak salad Spicy Tenderloin Steak salad With peri peri INR 275 CHAR GRILLED LAMB CHOPS South African wild herb chops INR 650 Moroccan Chops INR 550 Turkish lamb Chops INR 550 Hyderabadi Akhni ke Chops INR 450 Wild Garlic and Rosemary chops INR 450 French Chopper chops INR 450 Cajun Style chops INR 650 Parsley Butter Spicy chops INR 550 Mexican spiced chops INR 450 Hamburgers/Subs John n celebs Boston hamburgers INR 450 Philly Cheese steak Sub INR 650 UNH Style Philly Cheese INR 550 Mexican Spice INR 450 Fresh -

Indian Culinary Terms

INDIAN CULINARY TERMS Akhni or Yakni :- Soup or stock. Alu:- Potato. Amriti:- A sweetmeat. Atta:- Wholemeal flour. Baffad:- A curry with meat and radish from Goa. Baghar/Tadka:- Tempering done after the dish has been prepared. Onions and a few spices or herbs are fried in a spoonful of fat and added to the cooked dish to improve flavour. Baked Hilsa:- An oily fish considered a delicacy., Smoked slightly—all bones removed and baked with anchovy essence, tomato sauce, salad oil, mustard, etc. Balushai:- A round ball made of dough, slightly flattened at the centre, fried and dipped in sugar syrup Barfi:- A fudge like sweet. Basundi:- Milk sweet. Bhajjia:- Slices of vegetables dipped in gram flour batter and fried crisp. Bhaji:- Another term for vegetable preparations. Bhaturas:- Slightly leavened bread baked on a grid and then fried Generally served with 'Chhole', a dish prepared out of whole chickpeas. Bhel Puri:- Crisp fried thin rounds of dough mixed with puffed rice, fried lentil, chopped onion, herbs and chutney. Bhindi:- Okra/Gumbo, an Indian vegetable known as ladies fingers. Bhujjia:- A North Indian vegetable preparation. Bharta:- Vegetable boiled or roasted in charcoal, peeled, mashed and sauteed with a little chopped onion and chillies. Biryani:- A rich preparation of rice. Parboiled rice is put in layers with a rich meat or vegetable curry and the whole is baked till cooked. Black Pepper:- The berry of the pepper vine dried with the skin on. Bombay Duck:- A small, phosphorescent, gelatinous fish, abundant at the surface of the salt waters of Bengal and Bombay. -

Atlas Product List

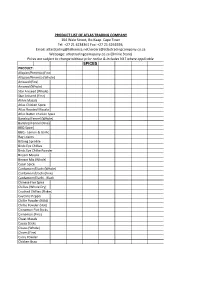

PRODUCT LIST OF ATLAS TRADING COMPANY 104 Wale Street, Bo-Kaap. Cape Town Tel. +27 21 4234361 Fax: +27 21 4261929, Email: [email protected]/[email protected] Webpage: atlastradingcomapany.co.za (Online Store) Prices are subject to change without prior notice & includes VAT where applicable SPICES PRODUCT: Allspice/Pimento (Fine) Allspice/Pimento (Whole) Aniseed (Fine) Aniseed (Whole) Star Aniseed (Whole) Star Aniseed (Fine) Akhni Masala Atlas Chicken Spice Atlas Roasted Masala Atlas Butter Chicken Spice Bariship/Fennel (Whole) Bariship/Fennel (Fine) BBQ Spice BBQ - Lemon & Garlic Bay Leaves Biltong Sprinkle Birds Eye Chillies Birds Eye Chillie Powder Biryani Masala Biryani Mix (Whole) Cajun Spice Cardamom/Elachi (Whole) Cardamom/Elachi (Fine) Cardamom/Elachi - Black Chinese Five Spice Chillies (Whole Dry) Crushed Chillies (Flakes) Cayenne Pepper Chillie Powder (Mild) Chillie Powder (Hot) Cinnamon Flat Sticks Cinnamon (Fine) Chaat Masala Cassia Sticks Cloves (Whole) Cloves (Fine) Curry Powder Chicken Braai SPICES PRODUCT: Chicken Tikka Masala Chicken Tikka Masala (Wet) Dhanya/Jeera Mix Dukkah Spice Father In Law Masala Fish Spice (Green) Fisherman's Spice Fenugreek/Methi Powder Garam Masala Garlic & Ginger Masala Ginger (Whole Dry) Ginger Powder Garlic Flakes Garlic Powder Jeera/Cumin (Whole/Seeds) Jeera/Cumin (Fine) Kashmiri Chillie Powder Kitchen King Masala Koljana/Coriander (Whole) Koljana/Coriander (Fine) Leaf Masala (12 In 1) Mace (Whole) Mace (Fine) Mother In Law Masala Mustard Powder Mix Spice Nutmeg (Whole) -

Download Menu

Welcome to the... PATHIA DISHES (Hot) SET MEAL FOR 1 PERSON A popular & fairly hot dish, originated from South India and famous for it’s rich flavour. BB Tandoori TA A5 A5 STARTERS: CHICKEN ................................... £5.70 CHICKEN OR LAMB TIKKA........£6.50 A2 PRAWN....................................... £5.95 MIX PATHIA..................................£6.50 POPPADOMS WITH ONION & MANGO CHUTNEY, 1 ONION BHAJI, 1 CHICKEN TIKKA, 1 LAMB TIKKA, 1 SHEEKH KEBAB KORMA DISHES A5 A8 Bradshaw MAIN MEALS: Preparation of mild spices with coconut and is of slightly sweet taste. A5 A8 A5 A8 CHOICE ANY ONE CURRY* CHICKEN TIKKA........................ £5.95 LAMB TIKKA............................... £6.40 A8 A8 CHICKEN................................... £6.20 LAMB........................................... £5.50 SUNDRIES: Tandoori Takeaway A2 A8 A2 A8 PRAWN....................................... £6.30 KING PRAWN.............................. £8.70 MUSHROOM BHAJI, PILAU RICE, NAAN BREAD & COKE CAN A2 A8 MIXED KORMA........................... £6.60 £12.95 114 Bradshaw Brow, Bolton BL2 3DD *Special curries £1.50 extra Est 1993 MALAYA DISHES A5 Cooked with pineapple, cream, herbs & spices. SET MEAL FOR 2 PERSONS CHICKEN OR LAMB TIKKA......£5.95A5 CHICKEN.....................................£5.50 LAMB......................................... £5.50 PRAWN......................................A5 ..£6.30 STARTERS: KING PRAWN..................A2 ...........£8.90 POPPADOMS WITH ONION & MANGO CHUTNEY, CHICKEN TIKKA, SHEEKH KEBAB MAIN MEALS: MEAT & VEGETABLE -

Thesis Hum 2020 Abrahams Ayesha.Pdf

The Crack in the Mountain Ayesha Abrahams ABRAYE003 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Town Master’s in Creative Writing Cape Facultyof of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2020 COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree.University It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: 1 February 2020 1 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town The Crack in the Mountain A Novel 2 For Shaheema, Ismail, Ilyaas, Alicia, and Ron. 3 Content Page Prologue……………………………………………………………….…..5 Chapter 1: The Last Supper………………………………………………21 Chapter 2: Acceptance…………………………………………………...30 Chapter 3: Into the Light………………………………………………....58 Chapter 4: Looking Back…………………………………………………69 Chapter 5: Room 804……………………………………………………..87 Chapter 6: The Crack in the Teacup……………………………………..101 Chapter 7: Books and Brownies……………………………………….…105 Chapter 8: Carlisle Curiosity……………………………………………..129 Chapter 9: The Detour……………………………………………………153 Chapter 10: Beautiful Things……………………………………………..160 Chapter 11: The Longest Month………………………………………….197 Chapter 12: Wedding Jitters……………………………………………....208 Chapter 13: What Happens When a Mountain Cracks?..............................231 Chapter 14: Not Tonight………………………………………………….241 Chapter 15: Movie Night………………………………………………....273 Chapter 16: The Crack in the Mountain………………………………….282 Chapter 17: Carlisle Compassion………………………………………....314 4 Prologue I call my mother by her first name because we look nothing alike.