Coral Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mississippi River Find

The Journal of Diving History, Volume 23, Issue 1 (Number 82), 2015 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 04/10/2021 06:15:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/32902 First Quarter 2015 • Volume 23 • Number 82 • 23 Quarter 2015 • Volume First Diving History The Journal of The Mississippi River Find Find River Mississippi The The Journal of Diving History First Quarter 2015, Volume 23, Number 82 THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER FIND This issue is dedicated to the memory of HDS Advisory Board member Lotte Hass 1928 - 2015 HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY USA A PUBLIC BENEFIT NONPROFIT CORPORATION PO BOX 2837, SANTA MARIA, CA 93457 USA TEL. 805-934-1660 FAX 805-934-3855 e-mail: [email protected] or on the web at www.hds.org PATRONS OF THE SOCIETY HDS USA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Ernie Brooks II Carl Roessler Dan Orr, Chairman James Forte, Director Leslie Leaney Lee Selisky Sid Macken, President Janice Raber, Director Bev Morgan Greg Platt, Treasurer Ryan Spence, Director Steve Struble, Secretary Ed Uditis, Director ADVISORY BOARD Dan Vasey, Director Bob Barth Jack Lavanchy Dr. George Bass Clement Lee Tim Beaver Dick Long WE ACKNOWLEDGE THE CONTINUED Dr. Peter B. Bennett Krov Menuhin SUPPORT OF THE FOLLOWING: Dick Bonin Daniel Mercier FOUNDING CORPORATIONS Ernest H. Brooks II Joseph MacInnis, M.D. Texas, Inc. Jim Caldwell J. Thomas Millington, M.D. Best Publishing Mid Atlantic Dive & Swim Svcs James Cameron Bev Morgan DESCO Midwest Scuba Jean-Michel Cousteau Phil Newsum Kirby Morgan Diving Systems NJScuba.net David Doubilet Phil Nuytten Dr. -

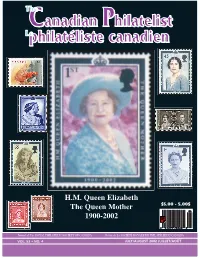

TCP July/Aug Pages

The CCanadiananadian PPhilatelisthilatelist Lephilatphilatéélisteliste canadiencanadien H.M. Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother $5.00 - 5,00$ 1900-2002 Journal of The ROYAL PHILATELIC SOCIETY OF CANADA Revue de La SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE DE PHILATÉLIE DU CANADA VOL. 53 • NO. 4 JULY/AUGUST 2002 JUILLET/AOÛT Le philatéliste canadien/TheCanadianPhilatelist Juillet -Août2002/171 Go with the proven leader CHARLES G. FIRBY AUCTIONS 1• 248•666•5333 TheThe CCanadiananadian PPhilatelisthilatelist LeLephilatphilatéélisteliste canadiencanadien Journal of The ROYAL PHILATELIC Revue de La SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE DE SOCIETY OF CANADA PHILATÉLIE DU CANADA Volume 53, No. 4 Number / Numéro 311 July - August 2002 Juillet – Août FEATURE ARTICLES / ARTICLES DE FOND ▲ The Queen Mum, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother by George Pepall 174 Double Print Errors on Canadian Stamps by Joseph Monteiro 177 The Sea Floor Post Office by Ken Lewis 182 The Date of Issue of the Two-Cent Registered Letter Stamp by George B. Arfken and Horace W. Harrison 184 The Early History of Envelopes by Dale Speirs 185 ▲ Blueberries and Mail by Sea by Captain Thomas Killam 188 The Surprises of Philately by Kimber A. Wald 190 ▲ Canada’s 1937 George VI Issue by J.J. Edward 193 Jamaican Jottings by “Busha” 197 The Short Story Column by “Raconteur” 200 Guidelines for Judging Youth Exhibits Directives pour Juger les Collections Jeunesse 202 Early German Cancels by “Napoleon” 207 In Memoriam – Harold Beaupre 209 172 / July - August 2002 The Canadian Philatelist / Le philatéliste canadien THE ROYAL PHILATELIC DEPARTMENTS / SERVICES SOCIETY OF CANADA LA SOCIÉTÉ ROYALE DE President’s Page / La page du président 211 PHILATÉLIE DU CANADA Patron Her Excellency The Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson Letters / Lettres 214 C.C., C.M.M., C.D., Governor General of Canada Président d’honneur Son Excellence le très honorable Coming Events / Calendrier 215 Adrienne Clarkson. -

Scuba Diving History

Scuba diving history Scuba history from a diving bell developed by Guglielmo de Loreno in 1535 up to John Bennett’s dive in the Philippines to amazing 308 meter in 2001 and much more… Humans have been diving since man was required to collect food from the sea. The need for air and protection under water was obvious. Let us find out how mankind conquered the sea in the quest to discover the beauty of the under water world. 1535 – A diving bell was developed by Guglielmo de Loreno. 1650 – Guericke developed the first air pump. 1667 – Robert Boyle observes the decompression sickness or “the bends”. After decompression of a snake he noticed gas bubbles in the eyes of a snake. 1691 – Another diving bell a weighted barrels, connected with an air pipe to the surface, was patented by Edmund Halley. 1715 – John Lethbridge built an underwater cylinder that was supplied via an air pipe from the surface with compressed air. To prevent the water from entering the cylinder, greased leather connections were integrated at the cylinder for the operators arms. 1776 – The first submarine was used for a military attack. 1826 – Charles Anthony and John Deane patented a helmet for fire fighters. This helmet was used for diving too. This first version was not fitted to the diving suit. The helmet was attached to the body of the diver with straps and air was supplied from the surfa 1837 – Augustus Siebe sealed the diving helmet of the Deane brothers’ to a watertight diving suit and became the standard for many dive expeditions. -

History of Scuba Diving About 500 BC: (Informa on Originally From

History of Scuba Diving nature", that would have taken advantage of this technique to sink ships and even commit murders. Some drawings, however, showed different kinds of snorkels and an air tank (to be carried on the breast) that presumably should have no external connecons. Other drawings showed a complete immersion kit, with a plunger suit which included a sort of About 500 BC: (Informaon originally from mask with a box for air. The project was so Herodotus): During a naval campaign the detailed that it included a urine collector, too. Greek Scyllis was taken aboard ship as prisoner by the Persian King Xerxes I. When Scyllis learned that Xerxes was to aack a Greek flolla, he seized a knife and jumped overboard. The Persians could not find him in the water and presumed he had drowned. Scyllis surfaced at night and made his way among all the ships in Xerxes's fleet, cung each ship loose from its moorings; he used a hollow reed as snorkel to remain unobserved. Then he swam nine miles (15 kilometers) to rejoin the Greeks off Cape Artemisium. 15th century: Leonardo da Vinci made the first known menon of air tanks in Italy: he 1772: Sieur Freminet tried to build a scuba wrote in his Atlanc Codex (Biblioteca device out of a barrel, but died from lack of Ambrosiana, Milan) that systems were used oxygen aer 20 minutes, as he merely at that me to arficially breathe under recycled the exhaled air untreated. water, but he did not explain them in detail due to what he described as "bad human 1776: David Brushnell invented the Turtle, first submarine to aack another ship. -

Thinking Art Thinking

CRMEP Books – Thinking art – cover 232 pp. Trim size 216 x 138 mm – Spine 18 mm 4-colour, matt laminate Caroline Bassett Dave Beech art Thinking Ayesha Hameed Klara Kemp-Welch Jaleh Mansoor Christian Nyampeta Peter Osborne Ludger Schwarte Keston Sutherland Giovanna Zapperi Thinking art materialisms, labours, forms isbn 978-1-9993337-4-4 edited by CRMEP BOOKS PETER OSBORNE 9 781999 333744 Thinking art Thinking art materialisms, labours, forms edited by PETER OSBORNE Published in 2020 by CRMEP Books Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy Penrhyn Road campus, Kingston University, Kingston upon Thames, kt1 2ee, London, UK www.kingston.ac.uk/crmep isbn 978-1-9993337-4-4 (pbk) isbn 978-1-9993337-5-1 (ebook) The electronic version of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC-BYNC-ND). For more information, please visit creativecommons.org. The right of the contributors to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 Designed and typeset in Calluna by illuminati, Grosmont Cover design by Lucy Morton at illuminati Printed by Short Run Press Ltd (Exeter) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Contents Preface PETER OSBORNE ix MATERIALISMS 1 Digital materialism: six-handed, machine-assisted, furious CAROLINE bASSETT 3 2 The consolation of new materialism KESTOn sUtHeRLAnD 29 ART & LABOUR 3 Art’s anti-capitalist ontology: on the historical roots of the -

Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports / Vol. 64 / No. 3 June 5, 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations and Reports CONTENTS CONTENTS (Continued) Introduction ............................................................................................................1 Gonococcal Infections ...................................................................................... 60 Methods ....................................................................................................................1 Diseases Characterized by Vaginal Discharge .......................................... 69 Clinical Prevention Guidance ............................................................................2 Bacterial Vaginosis .......................................................................................... 69 Special Populations ..............................................................................................9 Trichomoniasis ................................................................................................. 72 Emerging Issues .................................................................................................. 17 Vulvovaginal Candidiasis ............................................................................. 75 Hepatitis C ......................................................................................................... 17 Pelvic Inflammatory -

An Historic Maritime Salvage Company ® 40TH ANNIVERSARY EXPOSITION

The Journal of Diving History, Volume 23, Issue 4 (Number 85), 2015 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 03/10/2021 15:56:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/35934 Fourth Quarter 2015 • Volume 23 • Number 85 SORIMA An Historic Maritime Salvage Company ® 40TH ANNIVERSARY EXPOSITION EXPO 40 COURTESYPHOTO OF SCOTT PORTELLI THE SEA ATTEND The Greatest International Oceans MEADOWLANDS EXPOSITION CENTER | SECAUCUS | NEW JERSEY | MECEXPO.COM BENEATHExposition In The USA , , , REGISTER TODAY APRIL 1 2 3 2016 REGISTER TODAY ONLY 10 MINUTES FROM NYC • FREE PARKING EVERYWHERE! REGISTER ONLINE NOW AT WWW.BENEATHTHESEA.ORG BENEATH THE SEA™ 2016 DIVE & TRAVEL EXPOSITION 495 NEW ROCHELLE RD., STE. 2A, BRONXVILLE, NEW YORK 10708 914 - 664 - 4310 E-MAIL: [email protected] WWW.BENEATHTHESEA.ORG WWW.MECEXPO.COM HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY USA A PUBLIC BENEFIT NONPROFIT CORPORATION PO BOX 2837, SANTA MARIA, CA 93457 USA TEL. 805-934-1660 FAX 805-934-3855 e-mail: [email protected] or on the web at www.hds.org PATRONS OF THE SOCIETY HDS USA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Ernie Brooks II Carl Roessler Dan Orr, Chairman James Forte, Director Leslie Leaney Lee Selisky Sid Macken, President Janice Raber, Director Bev Morgan Greg Platt, Treasurer Ryan Spence, Director Steve Struble, Secretary Ed Uditis, Director ADVISORY BOARD Dan Vasey, Director Bob Barth Jack Lavanchy Dr. George Bass Clement Lee WE ACKNOWLEDGE THE CONTINUED Tim Beaver Dick Long SUPPORT OF THE FOLLOWING: Dr. Peter B. Bennett Krov Menuhin Dick Bonin Daniel Mercier FOUNDING CORPORATIONS Ernest H. Brooks II Joseph MacInnis, M.D. -

Rostocker Meeresbiologische Beiträge

Rostocker Meeresbiologische Beiträge Beiträge Zum Rostocker Forschungstauchersymposium 2019 Heft 30 Universität Rostock Institut für Biowissenschaften 2020 HERAUSGEBER DIESES HEFTES: Hendrik Schubert REDAKTION: Dirk Schories Gerd Niedzwiedz Hendrik Schubert HERSTELLUNG DER DRUCKVORLAGE: Christian Porsche CIP-KURZTITELAUFNAHME Rostocker Meeresbiologische Beiträge. Universität Rostock, Institut für Biowissenschaften. – Rostock, 2020. – 136 S. (Rostocker Meeresbiologische Beiträge; 30) ISSN 0943-822X © Universität Rostock, Institut für Biowissenschaften, 18051 Rostock REDAKTIONSADRESSE: Universität Rostock Institut für Biowissenschaften 18051 Rostock e-mail: [email protected] Tel. 0381 / 498-6071 Fax. 0381 / 498-6072 BEZUGSMÖGLICHKEITEN: Universität Rostock Universitätsbibliothek, Schriftentausch 18051 Rostock e-mail: [email protected] DRUCK: Druckerei Kühne & Partner GmbH & Co KG Umschlagfoto Titel: Unterwasseraufnahmen und Abbildung des Riffs in Nienhagen, [Uwe Friedrich, style-kueste.de] Rückseite: Gruppenbild der Forschungstauchertagung [Thomas Rahr, Universität Rostock, ITMZ] 2 Inhalt Seite FISCHER, P. 5 Vorwort NIEDZWIEDZ, G. 7 25 Jahre Forschungstaucherausbildung in Rostock – eine Geschichte mit langer Vorgeschichte VAN LAAK, U. 39 Der Tauchunfall als misslungene Prävention: Ergebnisse aus der DAN Europe Feldforschung MOHR, T. 51 Überblick zum Forschungsprojekt „Riffe in der Ostsee“ NIEDZWIEDZ, G. & SCHORIES, D. 65 Georeferenzierung von Unterwasserdaten: Iststand und Perspektiven SCHORIES, D. 81 Ein kurzer Ausschnitt über wissenschaftliches Fotografieren Unter- wasser und deren Anwendung WEIGELT, R., HENNICKE, J. & VON NORDHEIM, H. 93 Ein Blick zurück, zwei nach vorne – Forschungstauchen am Bundes- amt für Naturschutz zum Schutz der Meere AUGUSTIN, C. B., BÜHLER, A. & SCHUBERT, H. 103 Comparison of different methods for determination of seagrass distribution in the Southern Baltic Sea Coast SCHORIES, D., DÍAZ, M.-J., GARRIDO, I., HERAN, T., HOLTHEUER, J., KAPPES, J. 117 J., KOHLBERG, G. -

2 Accidents De Décompression D'origine Médullaire En

AIX-MARSEILLE UNIVERSITE Président : Yvon BERLAND FACULTE DES SCIENCES MEDICALES ET PARAMEDICALES Administrateur provisoire: Georges LEONETTI Affaires Générales : Patrick DESSI Professions Paramédicales : Philippe BERBIS Assesseurs : aux Etudes : Jean-Michel VITON à la Recherche : Jean-Louis MEGE aux Prospectives Hospitalo-Universitaires : Frédéric COLLART aux Enseignements Hospitaliers : Patrick VILLANI à l’Unité Mixte de Formation Continue en Santé : Fabrice BARLESI pour le Secteur Nord : Stéphane BERDAH aux centres hospitaliers non universitaires : Jean-Noël ARGENSON Chargés de mission : 1er cycle : Jean-Marc DURAND et Marc BARTHET 2ème cycle : Marie-Aleth RICHARD 3eme cycle DES/DESC : Pierre-Edouard FOURNIER Licences-Masters-Doctorat : Pascal ADALIAN DU-DIU : Véronique VITTON Stages Hospitaliers : Franck THUNY Sciences Humaines et Sociales : Pierre LE COZ Préparation à l’ECN : Aurélie DAUMAS Démographie Médicale et Filiarisation : Roland SAMBUC Relations Internationales : Philippe PAROLA Etudiants : Arthur ESQUER Chef des services généraux : Déborah ROCCHICCIOLI Chefs de service : Communication : Laetitia DELOUIS Examens : Caroline MOUTTET Intérieur : Joëlle FAVREGA Maintenance : Philippe KOCK Scolarité : Christine GAUTHIER DOYENS HONORAIRES M. Yvon BERLAND M. André ALI CHERIF M. Jean-François PELLISSIER Mis à jour 01/01/2019 PROFESSEURS HONORAIRES MM AGOSTINI Serge MM FAVRE Roger ALDIGHIERI René FIECHI Marius ALESSANDRINI Pierre FARNARIER Georges ALLIEZ Bernard FIGARELLA Jacques AQUARON Robert FONTES Michel -

Pacific Northwest Diver BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE & WEB SITE PROMOTING UNDERWATER PHOTOGRAPHY, EDUCATION, & TRAVEL in the PACIFIC NORTHWEST | JANUARY, 2012

PPacificUBLICATION OF THE PACIFIC Northwest NORTHWEST UNDERWATER PHOTOGRA DiverPHIC SOCIETY BRITISH COLUMBIA | WASHINGTON | OREGON | JANUARY, 2012 Page 1 Gunnel Condo | Janna Nichols Pacific Northwest Diver BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE & WEB SITE PROMOTING UNDERWATER PHOTOGRAPHY, EDUCATION, & TRAVEL IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST | JANUARY, 2012 In this Issue 3 Nanaimo to Corvallis 3 Subscribing to Pacific Northwest Diver 3 From the Archives: First Underwater Photo, 1893 3 Featured Photographer: Janna Nichols 4 News Corner 7 REEF 7 Andy Lamb Joins PNW Diver Team 7 Underwater Photo Workshops 7 Call for Critter Photos 8 Nudibranch ID App 8 Congrats to Pat Gunderson & Laurynn Evans 8 Feartured Operator/Resort: Sea Dragon Charters 9 Photographers & Videographers 11 British Columbia: John Melendez 11 Washington: Mike Meagher 13 Oregon: Aaron Gifford 15 Dive Travel Corner 17 Grand Bahama Island: Dolphins, Sharks, & Cavern 17 La Paz: Whale Sharks, Sea Lions, & Hammerheads 17 Technical Corner 18 Subsee Super Macro 18 PNW Diver Team 20 iPhone Users: Your PDF viewer does not support active links. To view video and use other links, we suggest the ap Goodreader <http://www.goodiware.com/goodreader.html>. Page 2 Pacific Northwest Diver: In This Issue Welcome to the January issue of Pacific Northwest Diver! This issue’s featured photographer is Janna Nichols. Janna is well know to the dive community, as she is the outreach coordinator for REEF. Not only is she an outstanding creature ID”er”, she is an excellent photographer. Our featured operator is Sea Dragon Charters in Howe Sound and Nanaimo, and we will be checking out photos from John Melendez in Vancouver, BC, Mike Meagher in Bellingham (be sure to watch the newly hatched wolf eel swimming in front of dad), and Aaron Giffords from Corvallis diving off of Newport, Oregon. -

An Updated Short History of the British Diving Apparatus Manufacturers

18 The International Journal of Diving History The International Journal of Diving History 19 Fig. 1. Some key persons from the firm of Siebe Gorman. 1a. (Christian) Augustus Siebe An Updated Short History of the British Diving Apparatus (1788-1872). Company founder. Manufacturers, Siebe Gorman and Heinke 1b. William Augustus Gorman (formerly O’Gorman; 1834-1904). by Michael Burchett, HDS, and Robert Burchett, HDS. Joint partner with Henry H. Siebe (1830-1885) at Siebe & Gorman (later Siebe Gorman & Co.). PART 1. THE SIEBE GORMAN COMPANY 1c. Sir Robert Henry Davis Introduction 1a. 1b. 1c. (1870-1965). Managing Director This account endeavours to produce a short, updated history of the Siebe Gorman and Heinke of Siebe Gorman & Co. manufacturing companies using past and present sources of literature. It does not attempt to include every aspect of the two company histories, but concentrates on key events with an emphasis on 1d. Henry Albert Fleuss the manufacture of diving apparatus. However, an understanding of their histories is not complete (1851-1933). Designer of the first without some knowledge of the social history and values of the period. Victorian and Edwardian practical ‘self-contained breathing society engendered moral values such as hard work, thrift, obedience and loyalty within a class-ridden apparatus’. system, in which poverty, harsh working conditions and basic education were normal for the working 1e. Professor John Scott Haldane classes. With intelligence and application, people could ‘better themselves’ and gain respect in an age of (1860-1936). Diving physiologist innovation, when Britain led the industrial world. who produced the first naval The businesses of Augustus Siebe and ‘Siebe, Gorman’ (in one form or another) survived for over 170 ‘Decompression Dive Tables’. -

Journal of Film Preservation

Film Preservation Journal of Revue de la Fédération Internationale des Archives du Film 52 • April / avril 1996 Published by the International Federation of Film Archives Volume XXV Journal of Film Preservation Volume XXV N° 52 Special Section: Preserving the Non-Fiction Films Los Angeles Symposium on non fiction films: 2 Working in the Film World of Non Fiction by William T. Murphy 5 Non Fiction Film and National Culture by Janet McBain 7 The Massive Mess of Mass Memory by Iola Baines and Gwenan Owen 15 Artifacts of Culture Sherlock Junior (Buster Keaton, USA, 1924) by Karen Ishizuka Still courtesy of George Eastman House, 20 Collecting Films of the Jewish Diaspora: International Museum of Photography and Film, Rochester, N.Y. The Role of the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive by Marilyn Koolik FIAF News / Nouvelles de la FIAF 25 Some Thoughts on Accessing Film Collections by Sabine Lenk 28 Symposium on Archival Rights by Hoos Blotkamp Our New Affiliates / Nos nouveaux affiliés 36 Fundación Cinemateca del Caribe, Colombia News from the Affiliates / Nouvelles des Affiliés 36 Amsterdam 38 Buenos Aires 38 Los Angeles, AFI 40 Montréal April / avril 1996 41 New York, Anthology FA Journal of Film Preservation 42 Paris, CF Bisannuel / Biannual ISSN 1017-1126 43 Praha Copyright FIAF 1996 43 Valencia 46 Washington, Library of Congress Comité de Rédaction 48 Wien, FA Editorial Board Robert Daudelin New Restoration Projects Chief Editor / Editeur en Chef Nouveaux projets de restauration Paolo Cherchi Usai Mary Lea Bandy 49 Projecto Lumière Gian