Complex Numbers Basic Concepts of Complex Numbers Operations on Complex Numbers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Enigmatic Number E: a History in Verse and Its Uses in the Mathematics Classroom

To appear in MAA Loci: Convergence The Enigmatic Number e: A History in Verse and Its Uses in the Mathematics Classroom Sarah Glaz Department of Mathematics University of Connecticut Storrs, CT 06269 [email protected] Introduction In this article we present a history of e in verse—an annotated poem: The Enigmatic Number e . The annotation consists of hyperlinks leading to biographies of the mathematicians appearing in the poem, and to explanations of the mathematical notions and ideas presented in the poem. The intention is to celebrate the history of this venerable number in verse, and to put the mathematical ideas connected with it in historical and artistic context. The poem may also be used by educators in any mathematics course in which the number e appears, and those are as varied as e's multifaceted history. The sections following the poem provide suggestions and resources for the use of the poem as a pedagogical tool in a variety of mathematics courses. They also place these suggestions in the context of other efforts made by educators in this direction by briefly outlining the uses of historical mathematical poems for teaching mathematics at high-school and college level. Historical Background The number e is a newcomer to the mathematical pantheon of numbers denoted by letters: it made several indirect appearances in the 17 th and 18 th centuries, and acquired its letter designation only in 1731. Our history of e starts with John Napier (1550-1617) who defined logarithms through a process called dynamical analogy [1]. Napier aimed to simplify multiplication (and in the same time also simplify division and exponentiation), by finding a model which transforms multiplication into addition. -

Irrational Numbers Unit 4 Lesson 6 IRRATIONAL NUMBERS

Irrational Numbers Unit 4 Lesson 6 IRRATIONAL NUMBERS Students will be able to: Understand the meanings of Irrational Numbers Key Vocabulary: • Irrational Numbers • Examples of Rational Numbers and Irrational Numbers • Decimal expansion of Irrational Numbers • Steps for representing Irrational Numbers on number line IRRATIONAL NUMBERS A rational number is a number that can be expressed as a ratio or we can say that written as a fraction. Every whole number is a rational number, because any whole number can be written as a fraction. Numbers that are not rational are called irrational numbers. An Irrational Number is a real number that cannot be written as a simple fraction or we can say cannot be written as a ratio of two integers. The set of real numbers consists of the union of the rational and irrational numbers. If a whole number is not a perfect square, then its square root is irrational. For example, 2 is not a perfect square, and √2 is irrational. EXAMPLES OF RATIONAL NUMBERS AND IRRATIONAL NUMBERS Examples of Rational Number The number 7 is a rational number because it can be written as the 7 fraction . 1 The number 0.1111111….(1 is repeating) is also rational number 1 because it can be written as fraction . 9 EXAMPLES OF RATIONAL NUMBERS AND IRRATIONAL NUMBERS Examples of Irrational Numbers The square root of 2 is an irrational number because it cannot be written as a fraction √2 = 1.4142135…… Pi(휋) is also an irrational number. π = 3.1415926535897932384626433832795 (and more...) 22 The approx. value of = 3.1428571428571.. -

Section 3.6 Complex Zeros

210 Chapter 3 Section 3.6 Complex Zeros When finding the zeros of polynomials, at some point you're faced with the problem x 2 −= 1. While there are clearly no real numbers that are solutions to this equation, leaving things there has a certain feel of incompleteness. To address that, we will need utilize the imaginary unit, i. Imaginary Number i The most basic complex number is i, defined to be i = −1 , commonly called an imaginary number . Any real multiple of i is also an imaginary number. Example 1 Simplify − 9 . We can separate − 9 as 9 −1. We can take the square root of 9, and write the square root of -1 as i. − 9 = 9 −1 = 3i A complex number is the sum of a real number and an imaginary number. Complex Number A complex number is a number z = a + bi , where a and b are real numbers a is the real part of the complex number b is the imaginary part of the complex number i = −1 Arithmetic on Complex Numbers Before we dive into the more complicated uses of complex numbers, let’s make sure we remember the basic arithmetic involved. To add or subtract complex numbers, we simply add the like terms, combining the real parts and combining the imaginary parts. 3.6 Complex Zeros 211 Example 3 Add 3 − 4i and 2 + 5i . Adding 3( − i)4 + 2( + i)5 , we add the real parts and the imaginary parts 3 + 2 − 4i + 5i 5 + i Try it Now 1. Subtract 2 + 5i from 3 − 4i . -

Niobrara County School District #1 Curriculum Guide

NIOBRARA COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT #1 CURRICULUM GUIDE th SUBJECT: Math Algebra II TIMELINE: 4 quarter Domain: Student Friendly Level of Resource Academic Standard: Learning Objective Thinking Correlation/Exemplar Vocabulary [Assessment] [Mathematical Practices] Domain: Perform operations on matrices and use matrices in applications. Standards: N-VM.6.Use matrices to I can represent and Application Pearson Alg. II Textbook: Matrix represent and manipulated data, e.g., manipulate data to represent --Lesson 12-2 p. 772 (Matrices) to represent payoffs or incidence data. M --Concept Byte 12-2 p. relationships in a network. 780 Data --Lesson 12-5 p. 801 [Assessment]: --Concept Byte 12-2 p. 780 [Mathematical Practices]: Niobrara County School District #1, Fall 2012 Page 1 NIOBRARA COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT #1 CURRICULUM GUIDE th SUBJECT: Math Algebra II TIMELINE: 4 quarter Domain: Student Friendly Level of Resource Academic Standard: Learning Objective Thinking Correlation/Exemplar Vocabulary [Assessment] [Mathematical Practices] Domain: Perform operations on matrices and use matrices in applications. Standards: N-VM.7. Multiply matrices I can multiply matrices by Application Pearson Alg. II Textbook: Scalars by scalars to produce new matrices, scalars to produce new --Lesson 12-2 p. 772 e.g., as when all of the payoffs in a matrices. M --Lesson 12-5 p. 801 game are doubled. [Assessment]: [Mathematical Practices]: Domain: Perform operations on matrices and use matrices in applications. Standards:N-VM.8.Add, subtract and I can perform operations on Knowledge Pearson Alg. II Common Matrix multiply matrices of appropriate matrices and reiterate the Core Textbook: Dimensions dimensions. limitations on matrix --Lesson 12-1p. 764 [Assessment]: dimensions. -

Complex Eigenvalues

Quantitative Understanding in Biology Module III: Linear Difference Equations Lecture II: Complex Eigenvalues Introduction In the previous section, we considered the generalized two- variable system of linear difference equations, and showed that the eigenvalues of these systems are given by the equation… ± 2 4 = 1,2 2 √ − …where b = (a11 + a22), c=(a22 ∙ a11 – a12 ∙ a21), and ai,j are the elements of the 2 x 2 matrix that define the linear system. Inspecting this relation shows that it is possible for the eigenvalues of such a system to be complex numbers. Because our plants and seeds model was our first look at these systems, it was carefully constructed to avoid this complication [exercise: can you show that http://www.xkcd.org/179 this model cannot produce complex eigenvalues]. However, many systems of biological interest do have complex eigenvalues, so it is important that we understand how to deal with and interpret them. We’ll begin with a review of the basic algebra of complex numbers, and then consider their meaning as eigenvalues of dynamical systems. A Review of Complex Numbers You may recall that complex numbers can be represented with the notation a+bi, where a is the real part of the complex number, and b is the imaginary part. The symbol i denotes 1 (recall i2 = -1, i3 = -i and i4 = +1). Hence, complex numbers can be thought of as points on a complex plane, which has real √− and imaginary axes. In some disciplines, such as electrical engineering, you may see 1 represented by the symbol j. √− This geometric model of a complex number suggests an alternate, but equivalent, representation. -

How to Show That Various Numbers Either Can Or Cannot Be Constructed Using Only a Straightedge and Compass

How to show that various numbers either can or cannot be constructed using only a straightedge and compass Nick Janetos June 3, 2010 1 Introduction It has been found that a circular area is to the square on a line equal to the quadrant of the circumference, as the area of an equilateral rectangle is to the square on one side... -Indiana House Bill No. 246, 1897 Three problems of classical Greek geometry are to do the following using only a compass and a straightedge: 1. To "square the circle": Given a circle, to construct a square of the same area, 2. To "trisect an angle": Given an angle, to construct another angle 1/3 of the original angle, 3. To "double the cube": Given a cube, to construct a cube with twice the area. Unfortunately, it is not possible to complete any of these tasks until additional tools (such as a marked ruler) are provided. In section 2 we will examine the process of constructing numbers using a compass and straightedge. We will then express constructions in algebraic terms. In section 3 we will derive several results about transcendental numbers. There are two goals: One, to show that the numbers e and π are transcendental, and two, to show that the three classical geometry problems are unsolvable. The two goals, of course, will turn out to be related. 2 Constructions in the plane The discussion in this section comes from [8], with some parts expanded and others removed. The classical Greeks were clear on what constitutes a construction. Given some set of points, new points can be defined at the intersection of lines with other lines, or lines with circles, or circles with circles. -

Hypercomplex Algebras and Their Application to the Mathematical

Hypercomplex Algebras and their application to the mathematical formulation of Quantum Theory Torsten Hertig I1, Philip H¨ohmann II2, Ralf Otte I3 I tecData AG Bahnhofsstrasse 114, CH-9240 Uzwil, Schweiz 1 [email protected] 3 [email protected] II info-key GmbH & Co. KG Heinz-Fangman-Straße 2, DE-42287 Wuppertal, Deutschland 2 [email protected] March 31, 2014 Abstract Quantum theory (QT) which is one of the basic theories of physics, namely in terms of ERWIN SCHRODINGER¨ ’s 1926 wave functions in general requires the field C of the complex numbers to be formulated. However, even the complex-valued description soon turned out to be insufficient. Incorporating EINSTEIN’s theory of Special Relativity (SR) (SCHRODINGER¨ , OSKAR KLEIN, WALTER GORDON, 1926, PAUL DIRAC 1928) leads to an equation which requires some coefficients which can neither be real nor complex but rather must be hypercomplex. It is conventional to write down the DIRAC equation using pairwise anti-commuting matrices. However, a unitary ring of square matrices is a hypercomplex algebra by definition, namely an associative one. However, it is the algebraic properties of the elements and their relations to one another, rather than their precise form as matrices which is important. This encourages us to replace the matrix formulation by a more symbolic one of the single elements as linear combinations of some basis elements. In the case of the DIRAC equation, these elements are called biquaternions, also known as quaternions over the complex numbers. As an algebra over R, the biquaternions are eight-dimensional; as subalgebras, this algebra contains the division ring H of the quaternions at one hand and the algebra C ⊗ C of the bicomplex numbers at the other, the latter being commutative in contrast to H. -

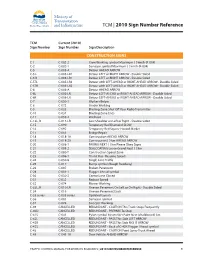

2010 Sign Number Reference for Traffic Control Manual

TCM | 2010 Sign Number Reference TCM Current (2010) Sign Number Sign Number Sign Description CONSTRUCTION SIGNS C-1 C-002-2 Crew Working symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-2 C-002-1 Surveyor symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-5 C-005-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-5 L C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5 R C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5TL C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-5TR C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6 C-006-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-6L C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6R C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-7 C-050-1 Workers Below C-8 C-072 Grader Working C-9 C-033 Blasting Zone Shut Off Your Radio Transmitter C-10 C-034 Blasting Zone Ends C-11 C-059-2 Washout C-13L, R C-013-LR Low Shoulder on Left or Right - Double Sided C-15 C-090 Temporary Red Diamond SLOW C-16 C-092 Temporary Red Square Hazard Marker C-17 C-051 Bridge Repair C-18 C-018-1A Construction AHEAD ARROW C-19 C-018-2A Construction ( ) km AHEAD ARROW C-20 C-008-1 PAVING NEXT ( ) km Please Obey Signs C-21 C-008-2 SEALCOATING Loose Gravel Next ( ) km C-22 C-080-T Construction Speed Zone C-23 C-086-1 Thank You - Resume Speed C-24 C-030-8 Single Lane Traffic C-25 C-017 Bump symbol (Rough Roadway) C-26 C-007 Broken Pavement C-28 C-001-1 Flagger Ahead symbol C-30 C-030-2 Centre Lane Closed C-31 C-032 Reduce Speed C-32 C-074 Mower Working C-33L, R C-010-LR Uneven Pavement On Left or On Right - Double Sided C-34 -

CHAPTER 8. COMPLEX NUMBERS Why Do We Need Complex Numbers? First of All, a Simple Algebraic Equation Like X2 = −1 May Not Have

CHAPTER 8. COMPLEX NUMBERS Why do we need complex numbers? First of all, a simple algebraic equation like x2 = 1 may not have a real solution. − Introducing complex numbers validates the so called fundamental theorem of algebra: every polynomial with a positive degree has a root. However, the usefulness of complex numbers is much beyond such simple applications. Nowadays, complex numbers and complex functions have been developed into a rich theory called complex analysis and be- come a power tool for answering many extremely difficult questions in mathematics and theoretical physics, and also finds its usefulness in many areas of engineering and com- munication technology. For example, a famous result called the prime number theorem, which was conjectured by Gauss in 1849, and defied efforts of many great mathematicians, was finally proven by Hadamard and de la Vall´ee Poussin in 1896 by using the complex theory developed at that time. A widely quoted statement by Jacques Hadamard says: “The shortest path between two truths in the real domain passes through the complex domain”. The basic idea for complex numbers is to introduce a symbol i, called the imaginary unit, which satisfies i2 = 1. − In doing so, x2 = 1 turns out to have a solution, namely x = i; (actually, there − is another solution, namely x = i). We remark that, sometimes in the mathematical − literature, for convenience or merely following tradition, an incorrect expression with correct understanding is used, such as writing √ 1 for i so that we can reserve the − letter i for other purposes. But we try to avoid incorrect usage as much as possible. -

Lecture 15: Section 2.4 Complex Numbers Imaginary Unit Complex

Lecture 15: Section 2.4 Complex Numbers Imaginary unit Complex numbers Operations with complex numbers Complex conjugate Rationalize the denominator Square roots of negative numbers Complex solutions of quadratic equations L15 - 1 Consider the equation x2 = −1. Def. The imaginary unit, i, is the number such that p i2 = −1 or i = −1 Power of i p i1 = −1 = i i2 = −1 i3 = i4 = i5 = i6 = i7 = i8 = Therefore, every integer power of i can be written as i; −1; −i; 1. In general, divide the exponent by 4 and rewrite: ex. 1) i85 2) (−i)85 3) i100 4) (−i)−18 L15 - 2 Def. Complex numbers are numbers of the form a + bi, where a and b are real numbers. a is the real part and b is the imaginary part of the complex number a + bi. a + bi is called the standard form of a complex number. ex. Write the number −5 as a complex number in standard form. NOTE: The set of real numbers is a subset of the set of complex numbers. If b = 0, the number a + 0i = a is a real number. If a = 0, the number 0 + bi = bi, is called a pure imaginary number. Equality of Complex Numbers a + bi = c + di if and only if L15 - 3 Operations with Complex Numbers Sum: (a + bi) + (c + di) = Difference: (a + bi) − (c + di) = Multiplication: (a + bi)(c + di) = NOTE: Use the distributive property (FOIL) and remember that i2 = −1. ex. Write in standard form: 1) 3(2 − 5i) − (4 − 6i) 2) (2 + 3i)(4 + 5i) L15 - 4 Complex Conjugates Def. -

Glossary of Linear Algebra Terms

INNER PRODUCT SPACES AND THE GRAM-SCHMIDT PROCESS A. HAVENS 1. The Dot Product and Orthogonality 1.1. Review of the Dot Product. We first recall the notion of the dot product, which gives us a familiar example of an inner product structure on the real vector spaces Rn. This product is connected to the Euclidean geometry of Rn, via lengths and angles measured in Rn. Later, we will introduce inner product spaces in general, and use their structure to define general notions of length and angle on other vector spaces. Definition 1.1. The dot product of real n-vectors in the Euclidean vector space Rn is the scalar product · : Rn × Rn ! R given by the rule n n ! n X X X (u; v) = uiei; viei 7! uivi : i=1 i=1 i n Here BS := (e1;:::; en) is the standard basis of R . With respect to our conventions on basis and matrix multiplication, we may also express the dot product as the matrix-vector product 2 3 v1 6 7 t î ó 6 . 7 u v = u1 : : : un 6 . 7 : 4 5 vn It is a good exercise to verify the following proposition. Proposition 1.1. Let u; v; w 2 Rn be any real n-vectors, and s; t 2 R be any scalars. The Euclidean dot product (u; v) 7! u · v satisfies the following properties. (i:) The dot product is symmetric: u · v = v · u. (ii:) The dot product is bilinear: • (su) · v = s(u · v) = u · (sv), • (u + v) · w = u · w + v · w. -

0.999… = 1 an Infinitesimal Explanation Bryan Dawson

0 1 2 0.9999999999999999 0.999… = 1 An Infinitesimal Explanation Bryan Dawson know the proofs, but I still don’t What exactly does that mean? Just as real num- believe it.” Those words were uttered bers have decimal expansions, with one digit for each to me by a very good undergraduate integer power of 10, so do hyperreal numbers. But the mathematics major regarding hyperreals contain “infinite integers,” so there are digits This fact is possibly the most-argued- representing not just (the 237th digit past “Iabout result of arithmetic, one that can evoke great the decimal point) and (the 12,598th digit), passion. But why? but also (the Yth digit past the decimal point), According to Robert Ely [2] (see also Tall and where is a negative infinite hyperreal integer. Vinner [4]), the answer for some students lies in their We have four 0s followed by a 1 in intuition about the infinitely small: While they may the fifth decimal place, and also where understand that the difference between and 1 is represents zeros, followed by a 1 in the Yth less than any positive real number, they still perceive a decimal place. (Since we’ll see later that not all infinite nonzero but infinitely small difference—an infinitesimal hyperreal integers are equal, a more precise, but also difference—between the two. And it’s not just uglier, notation would be students; most professional mathematicians have not or formally studied infinitesimals and their larger setting, the hyperreal numbers, and as a result sometimes Confused? Perhaps a little background information wonder .