Country House Libraries and the History of Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan 2018 – 2033 Final PDF

Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan 2018 – 2033 Final PDF Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan 2018 - 2033 Pyrton Parish Council Planning for the future of the parish V11.0 5th February 2018 Page 1 of 57 Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan 2018 – 2033 Final PDF Contents 1. Foreword 5 2. Executive summary 7 2.1. Background to neighbourhood plans 7 2.2. Preparation of the Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan (PNP) 7 2.3. Sensitive local context 8 2.4. Key factors bearing on the PNP 8 2.5. Proposed sites for development 9 3. Introduction and background 10 3.1. Neighbourhood planning and its purpose 10 3.1.1. What is neighbourhood planning? 10 3.1.2. What is a NP? 10 3.1.3. What can a NP include? 10 3.1.4. Basic conditions for a NP 11 3.1.5. Neighbourhood plan area 11 3.1.6. Reasons for preparing a NP 12 3.1.7. Structure of the plan 13 4. Description of Pyrton Parish 14 4.1. Introduction 14 4.2. Location 14 4.3. Historical context 15 4.4. Demographics 23 4.5. Local services and facilities 23 4.6. Employment 24 4.7. Other notable sites within parish 24 4.8. Planning policy context and applicable designations 26 4.8.1. Policy context 26 4.8.2. Planning and environmental designations 28 5. Purpose of the plan 32 5.1. Introduction 32 5.2. Consultation and data collection 32 5.2.1. What do residents value in Pyrton? 32 5.2.2. How to conserve and enhance the quality of the built and natural environment in Pyrton? 32 5.2.3. -

CSG Journal 31

Book Reviews 2016-2017 - ‘Castles, Siegeworks and Settlements’ In the LUP book, several key sites appear in various chapters, such as those on siege warfare and castles, some of which have also been discussed recently in academic journals. For example, a paper by Duncan Wright and others on Burwell in Cambridgeshire, famous for its Geoffrey de Mandeville association, has ap- peared in Landscape History for 2016, the writ- ers also being responsible for another paper, this on Cam’s Hill, near Malmesbury, Wilt- shire, that appeared in that county’s archaeolog- ical journal for 2015. Burwell and Cam’s Hill are but two of twelve sites that were targeted as part of the Lever- hulme project. The other sites are: Castle Carl- ton (Lincolnshire); ‘The Rings’, below Corfe (Dorset); Crowmarsh by Wallingford (Oxford- shire); Folly Hill, Faringdon (Oxfordshire); Hailes Camp (Gloucestershire); Hamstead Mar- shall, Castle I (Berkshire); Mountsorrel Castles, Siegeworks and Settlements: (Leicestershire); Giant’s Hill, Rampton (Cam- Surveying the Archaeology of the bridgeshire); Wellow (Nottinghamshire); and Twelfth Century Church End, Woodwalton (Cambridgeshire). Edited by Duncan W. Wright and Oliver H. The book begins with a brief introduction on Creighton surveying the archaeology of the twelfth centu- Publisher: Archaeopress Publishing ry in England, and ends with a conclusion and Publication date: 2016 suggestions for further research, such as on Paperback: xi, 167 pages battlefield archaeology, largely omitted (delib- Illustrations: 146 figures, 9 tables erately) from the project. A site that is recom- ISBN: 978-1-78491-476-9 mended in particular is that of the battle of the Price: £45 Standard, near Northallerton in North York- shire, an engagement fought successfully This is a companion volume to Creighton and against the invading Scots in 1138. -

Berkshire, Buckinghamshire & Oxfordshire County Guide

Historic churches in Berkshire Buckinghamshire Oxfordshire experience the passing of time visitchurches.org.uk/daysout 3 absorb an atmosphere of tranquility Step inside some of the churches of the Thames Valley and the Chilterns and you’ll discover art and craftsmanship to rival that of a museum. 2 1 The churches of the Thames Valley and the Chilterns contain some remarkable treasures. Yet sometimes it’s not the craftsmanship but the atmosphere that fires the imagination – the way windows scatter gems of light on an old tiled floor, or the peace of a quiet corner that has echoed with prayer for centuries. All the churches in this leaflet have been saved by The Churches Conservation Trust. The Trust is a charity that cares for more than 340 churches in England. This is one of 18 leaflets that highlight their history and treasures. dragon slayer For more information on the other guides in this series, fiery dragons and fearless saints as well as interactive maps and downloadable information, come alive in dramatic colour at see visitchurches.org.uk St Lawrence, Broughton 5 Lower Basildon, St Bartholomew 1 Berkshire A riverside church built by the people, for the people • 13th-century church near a beautiful stretch of the Thames • Eight centuries of remarkable memorials This striking flint-and-brick church stands in a pretty churchyard by the Thames, filled with memorials to past parishioners and, in early spring, a host of daffodils. Jethro Tull, the father of modern farming, has a memorial here (although the whereabouts of his grave is unknown) and there is a moving marble statue of two young brothers drowned in the Thames in 1886. -

List of Publications in Society's Library

OXFORD ARCHITECTURAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY RICHMOND ROOM, ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM Classified Shelf-List (Brought up-to-date by Tony Hawkins 1992-93) Note (2010): The collection is now stored in the Sackler Library CLASSIFICATION SCHEME A Architecture A1 General A2 Domestic A3 Military A4 Town Planning A5 Architects, biographies & memoirs A6 Periodicals B Gothic architecture B1 Theory B2 Handbooks B3 Renaissance architecture B4 Church restoration B5 Symbolism: crosses &c. C Continental and foreign architecture C1 General C2 France, Switzerland C3 Germany, Scandinavia C4 Italy, Greece C5 Asia D Church architecture: special features D1 General D2 Glass D3 Memorials, tombs D4 Brasses and incised slabs D5 Woodwork: roofs, screens &c. D6 Mural paintings D7 Miscellaneous fittings D8 Bells E Ecclesiology E1 Churches - England, by county E2 Churches - Scotland, Wales E3 Cathedrals, abbeys &c. F Oxford, county F1 Gazetteers, directories, maps &c. F2 Topography, general F3 Topography, special areas F4 Special subjects F5 Oxford diocese and churches, incl RC and non-conformist F6 Individual parishes, alphabetically G Oxford, city and university G1 Guidebooks G2 Oxford city, official publications, records G3 Industry, commerce G4 Education and social sciences G5 Town planning G6 Exhibitions, pageants &c H Oxford, history, descriptions & memoirs H1 Architecture, incl. church guides H2 General history and memoirs H3 Memoirs, academic J Oxford university J1 History J2 University departments & societies J3 Degree ceremonies J4 University institutions -

Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan 2018 - 2033

Pyrton NP - Landscape and Green Space Study Final PDF Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan 2018 - 2033 Landscape and Green Space Study V11.0 7th February 2018 Page 1 of 46 Pyrton NP - Landscape and Green Space Study Final PDF Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. References and Data Sources 4 3. The Origins of the Parish 5 4. Regional Landscape Character Context 8 4.1. Countryside Agency, Landscape Character Assessment Guidance for England and Scotland, 2002 8 4.2. South Oxfordshire Landscape Character Assessment (adopted July 2003) 9 4.2.1. Downs and Vale Fringe Landscapes 9 4.2.2. Parkland and Estate Farmland 10 4.2.3. Landscape Management Issues 10 4.2.4. Landscape Enhancement priorities 10 4.2.5. Planning and development issues 10 4.3. Chilterns AONB Character Assessment and Management Plan 11 4.4. Oxfordshire Wildlife and Landscape Study (OWLS) 13 4.4.1. Clay Vale 14 4.4.2. Estate Farmlands 15 4.4.3. River Meadowlands 16 4.4.4. Wooded Estate Slopes and Valley Sides 17 4.4.5. Wooded Farmland 18 5. Pyrton Landscape Types 21 5.1. The Pyrton Landscape 21 5.2. The Chiltern Escarpment and AONB 21 5.3. The Main Settlement of Pyrton 23 5.3.1. Views 26 5.3.2. Green Spaces 27 5.4. The Estate Parkland of Shirburn and Pyrton Manor 28 5.5. Hillside farmsteads in the North of the Parish (Clare and Golder) 30 5.6. Lower Lying Farmland 31 6. Maintaining a separate identity 33 6.1. Fields off Pyrton Lane (PYR2 and Pyrton Charity Field) 33 6.2. -

The Benson Bulletin Distributed Free to Over 2500 Homes in and Around Benson

The Benson Bulletin Distributed free to over 2500 homes in and around Benson This Month... For Parish Council News Village Queen’s Jubilee Celebrations News Benson Railway Activities Bensington Charity Information Benson Volunteer Helpline and Mill Stream Patients Panel Guide Local Clubs & Societies to Local Services April 2012 Volume 18 No. 7 Editor’s Column Anne Fowler writes... I hope everybody is enjoying this Spring warmth, and that we are all looking forward to the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations in Benson on Monday 4th June. Martyn Spence has written an article about it on Page 4. We Benson Volunteer hope to see you all there, so please pencil it into your diary. Helpline This is a packed issue this month, so apologies For assistance with travel to/from for any articles which I couldn’t fit in. However medical appointments I can use this space to include some notices Office open Mon-Fri 9-11am which I couldn’t fit in elsewhere: Call 01491 825992 The Science Exchange in Wallingford to ask for help or to volunteer is holding a talk called ‘Forked tongues: the evolution of human languages’ given email your letters/articles to by Professor Mark Pagel FRS, School of Biological Sciences, University of Reading on [email protected] Monday 21 May 2012, 8.00pm. The event is or deliver/send them to free, but arrive early as space is limited. Benson Parish Hall The Sinodun Inner Wheel Club are holding their annual Overseas Service Tea Party on Thursday May 10th in Benson Parish Hall at CONTENTS 2.00 for 2.30pm.There will be a raffle and stalls and an excellent tea. -

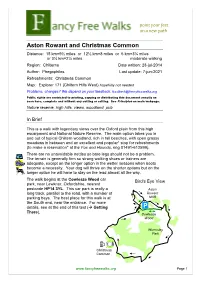

Aston Rowant and Christmas Common

point your feet on a new path Aston Rowant and Christmas Common Distance: 15 km=9½ miles or 12½ km=8 miles or 6 km=3¾ miles or 3¾ km=2¼ miles moderate walking Region: Chilterns Date written: 28-jul-2014 Author: Phegophilos Last update: 7-jun-2021 Refreshments: Christmas Common Map: Explorer 171 (Chiltern Hills West) hopefully not needed Problems, changes? We depend on your feedback: [email protected] Public rights are restricted to printing, copying or distributing this document exactly as seen here, complete and without any cutting or editing. See Principles on main webpage. Nature reserve, high hills, views, woodland, pub In Brief This is a walk with legendary views over the Oxford plain from this high escarpment and National Nature Reserve. The main option takes you in and out of typical Chiltern woodland, rich in tall beeches, with open grassy meadows in between and an excellent and popular* stop for refreshments (to make a reservation* at the Fox and Hounds , ring 01491-612599). There are no unavoidable nettles so bare legs should not be a problem. The terrain is generally firm so strong walking shoes or trainers are adequate, except on the longer option in the wetter seasons when boots become a necessity. Your dog will thrive on the shorter options but on the longer option he will have to stay on the lead almost all the way. The walk begins at the Cowleaze Wood car Bird's Eye View park, near Lewknor, Oxfordshire, nearest postcode HP14 3YL . This car park is really a Aston long track, parallel to the road, with a number of Rowant parking bays. -

The Medieval Manor at Stanton St John: a 700Th Anniversary?

The Medieval Manor at Stanton St John: A 700th Anniversary? B) IGEL GIL\10L R SLMMARY III rurnl Jt'an. a ""mber of repmn fHzd llltt'TflIW1L\ hal/I! INm lmdmllht!ll at 1M manor hOll\t In S/ll1ltOIJ 51 John. 7ilt.\t lull" bUlI aaompanU'd by (I \tlul) of tht fabric, tlU' la.lout (HId Ihi \tttltlg of the bUlldmg\, which has mcllall'd both a dtlldrochronologrr,,' nflll(l\L\ lIud a delalitd rl'rordUlg tlf Iht' fltl'allO'U of the howl'. thl' ,.t\IlIt.~ oJ till' \lUll) (Jrt prt'.~nJttd. logelhn urtlh (. rn',t"IL' of Iht h,,\/(mfal and la"d~alpt Ixlrkgruund to tht manor. Thru rcmgl'.\ oj an earlJ-l4th-ctnlllry \/U111'-bwfl holt:Jl' mn'll". mrlud"'K wllllt appmn 10 b,. (111 Hiner gatehOIL\1! u'lih fl thamber Otln; a..'i U'f'Illl.\ IU'l} !"rtll" ("ountfled two-sllm')' chamber b1()(k.~. Th,. lemon pm" oj a prt.\IHllfd gartlnobf' ,mnIJVl'j, and tlU'HII' 0/ (I 10,\/ hall hru beell prolll~uot1ally Ide-ntifif(1. All are \f/ u'l/Intl llll ember layout. u.oh parts of harm alUl ,\tabie,\\/tn111lmg. IULl1wg bun rt'bwll at t'anOlH tUfle,\. lhe early- 14th-rn/fury work rrNlI,d what muM luwp bp'II a r,lalively _mill II high-\/atu\ Iwu.. \e, facing a (nurf mid H/corporatmg (111 llIT1er gatehow:e - PO,Hlb(v /)fIn of a11 ullji1lHlied plan to dn'elop an IIlner (Ollrl. fllthrfe rangf\ dillf from thl' t"lIl' ofjohn tI, Sf john (I\t Lord Stjohn of Lllgl'Mm) who 1",1d IIv milnor fmm Co 1270 Imtll 1m death Hi JJ 16. -

Church New Look for Methodist Church

Watlington • Pyrton • Shirburn New Look for Method- ist Church New Look for Methodist Church Feb/March 2012 1 St. Mary’s Church St.Pyrton Mary’s Church invite you toPyrton their invite you to their DAFFODIL DAFFODIL SUNDAY SUNDAYth March 25 . th March 25 . 10am Benefice 10am Benefice Communion Service Communion Service Do come and see our Do come and see our Refreshments after the glorious wild daffodils and Refreshments after thediscover glorious the local wild history daffodils of and service discover the local history of service Pyrton and the Church Pyrton and the Church 2.15 pm2.15 & 3.30pmpm & 3.30 pm PuppetPuppet Show Show‘New Life’‘New for Life’ for childrenchildren and adults and adults by the by the SurreySurrey 20/20 20/20Puppet Puppet Team Team 2 – 5pm2 – Afternoon 5pm Afternoon teas will tea s will be on salebe on in sale the invillage the village hall hall EveryoneEveryone welcome welcome 2 Editorial Team Editor…Pauline Verbe [email protected] 01491 614350 Sub Editor...Ozanna Duffy [email protected] 01491 612859 St.Leonard’s Church News [email protected] 01491 614543 Val Kearney Advertising Manager [email protected] 01491 614989 Helen Wiedemann Front Cover Designer www.aplusbstudio.com 01491 612508 Benji Wiedemann Printer Simon Williams [email protected] 07919 891121 Wanted Magazine Distribution Organiser to help editor. All it involves is liaising with people who put the magazines through letter boxes! Please contact Pauline - 614350 PLEASE LET US HAVE YOUR COPY FOR April/May 2012 on or before March 5th 2012 Ministerial Teams p.50 & church wardens Features: St.Leonards News p. -

Old Master &British Paintings Evening Sale

Old Master &British Paintings Evening Sale London | 8 Dec 2010, 7:00 PM | L10036 LOT 45 PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE EARL OF MACCLESFIELD GEORGE STUBBS, A.R.A. LIVERPOOL 1724 - 1806 LONDON BROOD MARES AND FOALS signed lower right: Geo: Stubbs pinxit oil on canvas 99.7 by 188.6 cm.; 39 ¼ by 74 ¼ in. ESTIMATE 10,000,000 - 15,000,000 GBP PROVENANCE Colonel George Lane Parker (1724-1791) of Woodbury, Cambridgeshire, second son of George Parker, 2nd Earl of Macclesfield, of Shirburn Castle, Oxfordshire; by descent to elder his brother, Thomas Parker, 3rd Earl of Macclesfield, of Shirburn Castle, Oxfordshire; thence by descent to the present owner EXHIBITION Fig. 1 London, Society of Artists, Spring Exhibition 1768, no. 165; benjamin green, brood mares, London, Society of Artists, Exhibition in Honour of the King of Denmark, November 1768, mezzotint 1768 no 112 Texas, Kimbell Museum &London, National Gallery, Stubbs and the Horse, 2004, no. 57, p. XI, 114, 193-4 LITERATURE M. Parker, Countess of Macclesfield, Scattered Notices of Shirburn Castle, 1887, p. 39; W. Gilbey, Life of George Stubbs RA, London 1898, p. 169; J. Egerton, 'George Stubbs and the Landscape of Creswell Craggs,' Burlington Magazine, London 1984, p. 743; J. Egerton, George Stubbs 1724-1896, Exhibition Catalogue, Tate London 1984 a, p. 109; C. Lennox-Boyd, R. Dixon, and T. Clayton, George Stubbs: The Complete Engraved Fig. 2 Works, London 1989, pp. 74-76 with detail pp. 76-77 (cited below under engraved); george stubbs, 'portrait of a J. Egerton, George Stubbs: Painter, Yale, 2007, pp. -

4 Castle Road Shirburn WATLINGTON Oxfordshire

4 Castle Road Shirburn WATLINGTON Oxfordshire M.40 (J6) 1 mile Watlington 1.5 miles Henley on Thames 10 miles Oxford 14 miles A recently refurbished detached period cottage of great charm occupying an attractive semi-rural location close to Watlington. Available mid November Large Entrance Hall * Sitting Room * Family Room * Family Kitchen/Breakfast Room * 3 Bedrooms * Bathroom * Cloakroom * Large internal Store * Oil Fired Central Heating * South Facing Walled Garden * Store * Ample Parking £1,850 PCM Tel: 01491 614000 | www.robinsonsherston.co.uk 1 The High Street, Watlington, Oxfordshire, OX9 5PH | [email protected] Also at Henley-on-Thames 4 Castle Road, Shirburn, WATLINGTON, Oxfordshire, OX49 5DJ Contact the Watlington Office: 01491 614000 Tenure : Assured Shorthold Tenancy Bathroom: Panel enclosed bath with tiled splashback and mixer tap. Low Description: flush WC and washbasin in vanity unit. Wall mounted heated A recently refurbished detached period cottage of great charm towel rack. occupying an attractive semi-rural location close to Watlington. FIRST FLOOR Location: Landing: The property is situated about 1 mile from Watlington which is With door to: an historic and attractive market town at the foot of the Chiltern Hills. Apart from an ample range of local shops, Walk-in Store/Airing Cupboard facilities include a public library, schools, surgery and sports A large internal store that also houses an insulated hot water amenities. Junction 6 of the M40 is within a few miles of the cylinder with immersion heater. town providing easy access to the Midlands, London and the regional business centres of Oxford and High Wycombe. Bedroom 1: 15'0" x 12'1" (4.59 x 3.69) The accommodation is arranged as follows: A double room with outlook over the garden.