May 17, 2016 Don Kranendonk, District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Slope Mountain Lion Management Plan

West Slope Mountain Lion Plan: Sept 2, 2020 Colorado Parks and Wildlife COLORADO WEST SLOPE MOUNTAIN LION (Puma concolor) MANAGEMENT PLAN Northwest and Southwest Regions September 2020 Colorado Parks and Wildlife Approved by the Parks and Wildlife Commission on September 2, 2020 1 West Slope Mountain Lion Plan: Sept 2, 2020 Executive Summary Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s (CPW) aim for mountain lion management on the West Slope of Colorado is to preserve, protect, enhance and manage mountain lions for the use, benefit, and enjoyment of the state’s citizens and visitors. CPW strives to ensure that mountain lions continue to exist in relatively stable numbers in western Colorado for current and future generations to enjoy through hunting, occasional observation, and for their scientific, ecological and aesthetic value. This mountain lion management plan provides the framework for how CPW will achieve this goal in the Northwest and Southwest CPW Administrative Regions and replaces all existing West Slope Data Analysis Unit (DAU) lion management plans. This West Slope Mountain Lion Management Plan operates with the assertion that CPW’s thirteen DAU plans in western Colorado, each written in 2004 to describe a single lion population, are too small in spatial scale to properly manage solitary, low-density, wide- ranging carnivores like mountain lions. In many cases, sample sizes of mountain lion mortality data have been too small to reduce uncertainty in management conclusions and have not effectively informed past DAU objectives. This plan increases the size of the management unit at which analysis and evaluation will occur to a more appropriate scale: the CPW Administrative Northwest and Southwest Regions. -

March 13-April 30, 2020 Online Review Colorado Parks and Wildlife DRAFT

West Slope Mountain Lion Plan- DRAFT for online review March 13-April 30, 2020 online review Colorado Parks and Wildlife DRAFT COLORADO WEST SLOPE MOUNTAIN LION (Puma concolor) MANAGEMENT PLAN Northwest and Southwest Regions Spring 2020 Colorado Parks and Wildlife Approved by the Parks and Wildlife Commission on xx 1 West Slope Mountain Lion Plan- DRAFT for online review Executive Summary Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s (CPW) aim for mountain lion management on the West Slope of Colorado is to preserve, protect, enhance and manage mountain lions for the use, benefit, and enjoyment of the state’s citizens and visitors. CPW strives to ensure that mountain lions continue to exist in relatively stable numbers in western Colorado for current and future generations to enjoy through hunting, occasional observation, and for their scientific, ecological and aesthetic value. This mountain lion management plan provides the framework for how CPW will achieve this goal in the Northwest and Southwest CPW Administrative Regions and replaces all existing West Slope Data Analysis Unit (DAU) lion management plans. This West Slope Mountain Lion Management Plan operates with the assertion that CPW’s thirteen DAU plans in western Colorado, each written in 2004 to describe a single lion population, are too small in spatial scale to properly manage solitary, low-density, wide- ranging carnivores like mountain lions. In many cases, sample sizes of mountain lion mortality data have been too small to reduce uncertainty in management conclusions and have not effectively informed past DAU objectives. This plan increases the size of the management unit at which analysis and evaluation will occur to a more appropriate scale: the CPW Administrative Northwest and Southwest Regions. -

Energy Trail Colorado River Loma DOUGLAS PASS Rangely White River Oil Dinosaur ENERGY TRAIL River Shale 70

Did you know miners and oilmen have been working BOUNDLESS LANDSCAPES & SPIRITED PEOPLE in northwest Colorado for generations? Douglas Pass Green Energy Trail Colorado River Loma DOUGLAS PASS Rangely White River Oil Dinosaur ENERGY TRAIL River Shale 70 Section on RD 139* Mancos Shale In the 1930s, technology enabled oilmen to drill over a mile down to oil pockets and open Colorado’s most productive oil field; just south of Douglas Pass look for Green River shale. Roan Plateau Energy Trail Color photo: courtesy Mary Lee Morlang; historical Colorado River Grand Junction BOOK CLIFFS ROAN CLIFFS CALLAHAN MT. Parachute ROAN CLIFFS Rifle GRAND HOGBACK 70 photo: courtesy CHS History Collection ca. MCC-2568 1910 Section parallel to I-70 70 FAULT Mancos Shale It is estimated that 1.8 trillion barrels of oil exists in the waxy compound or kerogen of the shale of the Roan Cliffs—the world’s largest known source. Axial to Yampa Energy Trail Oil Field Tow Creek Tow Craig Hayden Milner Steamboat Springs Did you know a wealth of natural resources are found 70 Section on U.S. 40* in northwest Colorado? Shale Mancos Deep below northwest Colorado’s canyons and rivers, forests and wilderness, mountains and parks, mesas and plateaus—lie Starting in the 1870s, coal enticed miners to this region and geological expanses of fossil fuels and minerals. For centuries, continues as a way of life today; and in other geological layers coal, oil, natural gas, and oil shale have lured men to open cut oil is pumped from a depth of 2,500 feet. -

Record of Decision and Approved Resource Management Plan Amendment BLM/CO/PL-17/002

COLORADO RIVER VALLEY FIELD OFFICE ROAN PLATEAU PLANNING AREA Including Naval Oil Shale Reserves Numbers 1 & 3 Record of Decision and Approved Resource Management Plan Amendment BLM/CO/PL-17/002 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management 1001096.0002.04.01-B4588 Colorado State Office NOVEMBER 2016 BLM’s Mission To sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of America’s public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. This page intentionally left blank. Record of Decision and Approved Resource Management Plan Amendment for the Bureau of Land Management Roan Plateau Planning Area Colorado River Valley Field Office and White River Field Office BLM/CO/PL-17/002 Prepared by: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Colorado River Valley Field Office Silt, Colorado Cooperating Agencies: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Colorado Parks and Wildlife Garfield County Mesa County Rio Blanco County Town of Parachute City of Rifle November 2016 This page intentionally left blank. This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................ vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. ES-1 CHAPTER 1 RECORD OF DECISION FOR THE ROAN PLATEAU PLANNING AREA APPROVED RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN AMENDMENT .................................. 1-1 1.1 -

COMMUNITIES in GARFIELD COUNTY Colorado Is the 4Th Happiest State in the United States, Accordingly to Wallethub.Com

COMMUNITIES IN GARFIELD COUNTY Colorado is the 4th happiest state in the United States, accordingly to wallethub.com. This fact is usually of no surprise to people that live, work, and play within Garfield County, which offers a diversity of amenities, jobs and other lifestyle choices that attract and retain different people to each community. There are seven municipalities within Garfield County. In order of incorporation, the jurisdictions include Glenwood Springs, Carbondale, New Castle, Rifle, Parachute, Silt, and Carbonate. In addition, Battlement Mesa, a large unincorporated community, sits adjacent to the Town of Parachute, while Carbonate has no permanent residents. 14 15 CARBONDALE COLORADO Founded in 1888, the Town of Carbondale sits at the base of Mount Sopris, near the confluence of the Crystal and Roaring Fork rivers. Touted as one of the “Top 12 Towns” in the “50 Next Great Places to Live and Play” by National Geographic Adventure magazine, and as one of the 50 Best Places to Live/Most Active Towns by Men’s Journal magazine, Carbondale is a great base camp for recreation enthusiasts. Living at the foot of the magnificent 12,953-foot Mt. Sopris, there is plenty to do, including biking, hiking, “Gold Medal” fly-fishing, kayaking, and world-class skateboarding. In winter, excellent snow for cross-country skiing can be found at Spring Gulch, and beautiful snowmobiling and snowshoeing trails are accessible in all directions. World famous downhill skiing and snowboarding is 30 miles away in Aspen and Snowmass, or 15 miles away at Sunlight Mountain Resort near Glenwood Springs. At an altitude of 6,181 feet, the Carbondale area is characterized by an average of 295 days of sunshine, low humidity, cold but mild winters, and comfortable summers. -

Enterprise Gas Processing, LLC Enterprise Well-Tie Yard Limited Impact Review

Enterprise Gas Processing, LLC Enterprise Well-Tie Yard Limited Impact Review Submittal Item Tab 6 Land Suitability Analysis 4-502 (D) The Land Suitability Analysis includes the following information: 1. Public Access to site – There is no Public Access to the site. Authorized vehicles must enter off County Road 215 onto Garden Gulch road, which is privately owned and maintained. All traffic must sign in at a guard shack for clearance, upon entering and exiting Garden Gulch Road. 2. Access to adjoining Roadways – Garden Gulch Road is the only adjoining roadway to the proposed site. 3. Easements – There are two existing Easements. One located outside the southern fence line running East-West, and one located outside the eastern fence line running North-South. 4. Topography and Slope – The project area lies at the head of a draw on a relatively flat surface. Elevation at the site is approximately 8,300 feet. Rolling ridgetops, bisected by draws dominate the landscape view in the area. 5. Natural Features – The proposed site was previously used and abandoned as a laydown yard by IXP Inc. There are no significant natural features on-site or off-site. 6. Drainage Features – The project area is located in the Parachute-Rhone watershed, on a ridge between Circle Dot Gulch and Sheep Kill Gulch, where topography is generally flat. These gulches drain into the West Fork of the Parachute Creek. Flows then ultimately proceed to the Colorado River. There are no existing man-made drainages or impoundments. 7. Water – A potable water supply is not proposed on the property since the land use is for storage of construction operation and construction materials only and no habitated structures are proposed on site. -

Declaration of Meleah A

Case 2:16-cv-00285-SWS Document 27-2 Filed 12/02/16 Page 2 of 174 Case 2:16-cv-00285-SWS Document 27-2 Filed 12/02/16 Page 3 of 174 Case 2:16-cv-00285-SWS Document 27-2 Filed 12/02/16 Page 4 of 174 Case 2:16-cv-00285-SWS Document 27-2 Filed 12/02/16 Page 5 of 174 Case 2:16-cv-00285-SWS Document 27-2 Filed 12/02/16 Page 7 of 174 DECLARATION OF MELEAH A. GEERTSMA I, Meleah A. Geertsma, declare as follows: 1. I am a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (“NRDC”), where I work on NRDC’s campaign to control greenhouse gases from and address other impacts of oil and gas development. I have been an attorney with NRDC since 2010. 2. NRDC is a non-profit environmental membership organization that uses law, science, and the support of more than two million members and activists throughout the United States to protect wildlife and wild places and to ensure a safe and healthy environment for all living things. NRDC has a long-established history of working to protect public lands and clean air in states including Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Ohio, Alabama, Virginia, Mississippi, Florida, and more. These actions help protect NRDC’s members, who use and enjoy public lands across the country for a variety of purposes, including recreation, solitude, scientific study, and conservation of natural resources. In particular, NRDC has worked for decades to protect public lands, nearby communities, wildlife habitat and air quality from the threats posed by oil and gas development. -

Energy Field Tour 2003 (August 11-16) 2003

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Energy Field Tour 2003 (August 11-16) 2003 8-11-2003 AGENDA: Energy Field Tour 2003 University of Colorado Boulder. Natural Resources Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/energy-field-tour-2003 Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Animal Law Commons, Climate Commons, Energy and Utilities Law Commons, Energy Policy Commons, Environmental Engineering Commons, Environmental Law Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Geology Commons, Government Contracts Commons, Hydraulic Engineering Commons, Hydrology Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Legislation Commons, Mining Engineering Commons, Natural Resource Economics Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Nuclear Engineering Commons, Oil, Gas, and Energy Commons, Oil, Gas, and Mineral Law Commons, Power and Energy Commons, Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons, Science and Technology Law Commons, State and Local Government Law Commons, Urban Studies and Planning Commons, Water Law Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Citation Information University of Colorado Boulder. Natural Resources Law Center, "AGENDA: Energy Field Tour 2003" (2003). Energy Field Tour 2003 (August 11-16). https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/energy-field-tour-2003/1 Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural -

D3 P&D Del-Mont

BOCC MEETING TRANSMITTAL EST. 1883 Submitted By: Dean Cooper Date Submitted: 3/28/2017 Division/Elected Office: P&D/Engineering BOCC Meeting Date: 4/3/2017 Strategic Plan Priority # #2 - Improve and Maintain a Safe Transportation System Discussed with County Manager? Yes Date Discussed: 3/30/2017 Reviewed by County Attorney? Yes Date Reviewed: 3/30/2017 Discussed with Commissioners? Yes If so, when? 3/30/2017 Is a Public Hearing Required? No Does this item require a Resolution? No Included in Current Budget? Yes Annual Expense na - if no, attach a Budget Amendment Annual Revenue na Is this a Grant? No County's Match na Additional Employees Required? No If so, how many? na Is this subject to annual renewal? Yes Fiscal Rule #: 10J Is this a Bid Award? (If yes, attach bid summary) No Purchase Amount na New Employee Introduction (1st Meeting of each Month) Employee Name (Division/EO) Regular Agenda or Consent Agenda? Regular Program is New, Ongoing, or Temporary? Temp. Summary (note this text will be used for the BOCC agenda): Consideration and possible approval to extend the "Professional Services Agreement Civil Engineering and Land Surveying" with Del-Mont Consultants, Inc. for 1 year, effective through December 31, 2017, as allowed by the Agreement. The Amount of this extension shall not exceed $100,000 without Montrose County Authorization. This is a budgeted expense for 2017. Extension of Professional Services Agreement Field Engineering and Construction Support Services The "Professional Services Agreement Civil Engineering and Surveying Consulting Services" (Contract #2016-53) between Montrose County and Del-Mont Consultants, Inc. -

Ephemeral Archaeology on the Mountain of the Sorrel Deer, Delta County, Colorado

United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Colorado EPHEM RAL A CHAEOLOGY ON THE MOUNTAIN OF THE SORREL DEER Steven G. Baker ~UL TURAL RESOURCE SERIES NUMBER 32 EPHEMERAL ARCHAEOLOGY ON THE MOUNTAIN OF THE SORREL DEER, DELTA COUNTY, COLORADO by Steven G. Baker Colorado State Office Bureau of Land Management U.S. Department of the Interior Denver, Colorado 1991 EPHEMERAL ARCHAEOLOGY ON THE MOUNTAIN OF THE SORREL DEER, DELTA COUNTY, COLORADO by Steven G. Baker Principal Investigator CENTURIES RESEARCH, INC. Montrose, Colorado Originally Prepared for: Colorado Westmoreland, Inc. Paonia, Colorado September 1, 1987 For Submission to: Uncompahgre Resource Area Bureau of Land Management Montrose, Colorado Colorado BLM Antiquities Permit C-4O159c (December 31, 1986) CRI Project No. 382 CWI Contract No. CE-86-258 COPIES OF THIS DOCUMENT ARE AVAILABLE FROM: Colorado State Office Bureau of Land Management 2850 Youngfield Street Lakewood, Colorado 80215-7076 or Montrose District Office Bureau of Land Management 2465 South Townsend Avenue Montrose, Colorado 81401 THIS DOCUMENT IS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN AND MAY BE QUOTED. IF PORTIONS OF THIS WORK ARE USED, PLEASE CREDIT EITHER THE AUTHOR(S) AND/OR THE BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT. Cover Photo: The Grand Mesa 1ooki ng north across the Gunnison River Bottoms, near Delta, Colorado. The Spanish explorers of the 18th Century referred to Grand Mesa as La Sierra del Venado Alazan or The Mountain of the Sorrel Deer or Elk. Photo courtesy of Ben Walker, Delta, Colorado. Series Production: Frederic J. Athearn FOREWORD Small, nondescript, ephemeral archaeological sites are often ignored, surficially examined, and judged insignificant based upon a paucity of surface evidence. -

E47A - Wasatch and Uinta Mountains

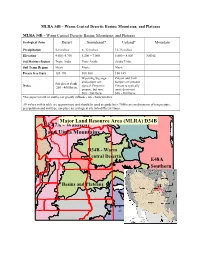

MLRA 34B – Warm Central Desertic Basins; Mountains; and Plateaus MLRA 34B – Warm Central Desertic Basins; Mountains; and Plateaus Ecological Zone Desert Semidesert* Upland* Mountain Precipitation 4-8 inches 8 -12 inches 12-16 inches Elevation 4,600 -5,700 5,200 – 7,000 6,000 – 8,000 NONE Soil Moisture Regime Typic Ardic Ustic Aridic Aridic Ustic Soil Temp Regime Mesic Mesic Mesic Freeze free Days 120-190 100-160 100-145 Wyoming big sage Pinyon and Utah and juniper are Juniper are present. Salt desert shrub Notes typical. Pinyon is Pinyon is typically 250 - 400 lbs/ac. present, but rare more dominant 300 - 500 lbs/ac 600 - 900 lbs/ac *the aspect (north or south) can greatly influence site characteristics. All values in this table are approximate and should be used as guidelines. Different combinations of temperature, precipitation and soil type can place an ecological site into different zones. Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) D34B E47A - Wasatch and Uinta Mountains D34B - Warm Central Desertic E48A Southern Rocky Mountains Basins and Plateaus 0408020 Miles 34B—Warm Central Desertic Basins and Plateaus This area is in Utah (70 percent) and Colorado (30 percent). It makes up about 12,850 square miles (33,290 square kilometers). The cities of Vernal, Roosevelt, Price, and Duchesne, Utah, and Grand Junction, Delta, and Montrose, Colorado, occur in this MLRA. Interstate 40 bisects the northern part of the area, and Interstate 70 bisects the southern part. The Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation and the western end of Dinosaur National Monument occur in this MLRA. Physiography This area is in the Canyon Lands (60 percent) and Uinta Basin (35 percent) Sections of the Colorado Plateaus Province of the Intermontane Plateaus. -

Roan Plateau Proposed Wilderness Area

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Energy Field Tour 2003 (August 11-16) 2003 8-12-2003 Day 2. Tuesday, August 12, 2003: Roan Plateau Proposed Wilderness Area Roan Plateau Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/energy-field-tour-2003 Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Animal Law Commons, Energy and Utilities Law Commons, Energy Policy Commons, Environmental Law Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Mining Engineering Commons, Natural Resource Economics Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Oil, Gas, and Mineral Law Commons, Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons, Urban Studies and Planning Commons, Water Law Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Citation Information Roan Plateau, "Day 2. Tuesday, August 12, 2003: Roan Plateau Proposed Wilderness Area" (2003). Energy Field Tour 2003 (August 11-16). https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/energy-field-tour-2003/3 Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School. William A. Wise Law Library C o l o r a d o UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER Getches-Wilkinson Center Collection Day 2. Tuesday, August 12, 2003: Roan Plateau Proposed Wilderness Area, in En e r g y Field T o u r 2003 (Natural Res. Law Ctr., Univ. of Colo. Sch. of Law 2003). Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School.