The Economic and Environmental Effects of Local Bus Service Deregulation in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Britain's Transition from Rail to Road-Based Food Distribution, 1919-1975 Thomas James Spain MA

‘Food Miles’: Britain’s Transition from Rail to Road-based Food Distribution, 1919-1975 Thomas James Spain MA Doctor of Philosophy University of York Railway Studies September 2016 Abstract Britain’s railways were essential for the development of the British economy throughout the nineteenth century; however, by 1919 their seemingly unassailable position as goods carriers was about to be eroded by the lorry. The railway strike of September 1919 had presented traders with an opportunity to observe the capabilities of road haulage, but there is no study which focuses on the process of modal shift in goods distribution from the trader’s perspective. This thesis therefore marks an important departure from the existing literature by placing goods transport into its working context. The importance of food as an everyday essential commodity adds a further dimension to the status of goods transport within Britain’s supply chain, particularly when the fragility of food products means that minimising the impact of distance, time and spoilage before consumption is vital in ensuring effective and practical logistical solutions. These are considered in a series of four case studies on specific food commodities and retail distribution, which also hypothesise that the modal shift from rail to road reflected the changing character of transport demand between 1919 and 1975. Consequently, this thesis explores the notion that the centre of governance over the supply chain transferred between food producers, manufacturers, government and chain retailer, thereby driving changes in transport technology and practice. This thesis uses archival material to provide a qualitative study into the food industry’s relationship with transport where the case studies incorporate supply chain analyses to permit an exploration of how changes in structure might have influenced the modal shift from rail to road distribution. -

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

Transport Act 1962 Is up to Date with All Changes Known to Be in Force on Or Before 08 July 2021

Status: Point in time view as at 13/06/2003. Changes to legislation: Transport Act 1962 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 08 July 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) Transport Act 1962 1962 CHAPTER 46 10 and 11 Eliz 2 An Act to provide for the re-organisation of the nationalised transport undertakings now carried on under the Transport Act 1947, and for that purpose to provide for the establishment of public authorities as successors to the British Transport Commission, and for the transfer to them of undertakings, parts of undertakings, property, rights, obligations and liabilities; to repeal certain enactments relating to transport charges and facilities and to amend in other respects the law relating to transport, inland waterways, harbours and port facilities; and for purposes connected with the matters aforesaid. [1st August 1962] Extent Information E1 For extent see s. 93(1) Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Act excluded by Transport Act 1981 (c. 56, SIF 126), s. 5(4), Sch. 4 Pt. I para. 2(1)(2) C2 Act extended by Transport Act 1981 (c. 56, SIF 126), s. 5(4), Sch. 4 Pt. I para. 4(2) C3 Power to amend and repeal conferred by Transport (Scotland) Act 1989 (c. 23, SIF 126), s. 14(3)(d) Commencement Information I1 Act not in force at Royal Assent see s. -

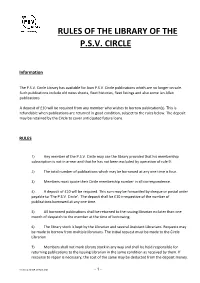

Rules of the Library of the P.S.V. Circle

RULES OF THE LIBRARY OF THE P.S.V. CIRCLE Information The P.S.V. Circle Library has available for loan P.S.V. Circle publications which are no longer on sale. Such publications include old news sheets, fleet histories, fleet listings and also some Ian Allan publications. A deposit of £10 will be required from any member who wishes to borrow publication(s). This is refundable when publications are returned in good condition, subject to the rules below. The deposit may be retained by the Circle to cover anticipated future loans. RULES 1) Any member of the P.S.V. Circle may use the library provided that his membership subscription is not in arrear and that he has not been excluded by operation of rule 9. 2) The total number of publications which may be borrowed at any one time is four. 3) Members must quote their Circle membership number in all correspondence. 4) A deposit of £10 will be required. This sum may be forwarded by cheque or postal order payable to 'The P.S.V. Circle'. The deposit shall be £10 irrespective of the number of publications borrowed at any one time. 5) All borrowed publications shall be returned to the issuing librarian no later than one month of despatch to the member at the time of borrowing. 6) The library stock is kept by the Librarian and several Assistant Librarians. Requests may be made to borrow from multiple librarians. The initial request must be made to the Circle Librarian. 7) Members shall not mark Library stock in any way and shall be held responsible for returning publications to the Issuing Librarian in the same condition as received by them. -

Transport Act 1985

Transport Act 1985 CHAPTER 67 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I GENERAL PROVISIONS RELATING TO ROAD PASSENGER TRANSPORT Abolition of road service licensing Section 1. Abolition of road service licensing. Meaning of " local service " 2. Local services. Traffic commissioners 3. Traffic commissioners. 4. Inquiries held by traffic commissioners. 5. Assistance for traffic commissioners in considering financial questions. Registration of local services 6. Registration of local services. 7. Application of traffic regulation conditions to local services subject to registration under section 6. 8. Enforcement of traffic regulation conditions, etc. 9. Appeals against traffic regulation conditions. Taxis and hire cars 10. Immediate hiring of taxis at separate fares. 11. Advance booking of taxis and hire cars at separate fares. 12. Use of taxis in providing local services. A ii c. 67 Transport Act 1985 Section 13. Provisions supplementary to sections 10 to 12. 14. Operation of taxis and private hire cars in Scotland for the carriage of passengers at separate fares. 15. Extension of taxi licensing in England and Wales. 16. Taxi licensing: control of numbers. 17. London taxi and taxi driver licensing: appeals. Modification of PSV requirements in relation to vehicles used for certain purposes 18. Exemption from PSV operator and driver licensing requirements of vehicles used under permits. 19. Permits in relation to use of buses by educational and other bodies. 20. Further provision with respect to permits under section 19. 21. Permits under section 19: regulations. 22. Community bus permits. 23. Further provision with respect to community bus permits. Further amendments with respect to PSV operators' licences 24. Limit on number of vehicles to be used under a restricted licence. -

Acu Handbook £8.00 2015

ACU HANDBOOK HANDBOOK ACU £8.00 2015 ARENA TRIALS BEACH CROSS BEACH RACING BIKE TRIALS BYMX CYCLE TRIALS DRAG ENDURO GRASS TRACK HARE & HOUNDS HILL CLIMB MOTOCROSS POCKET BIKES QUAD ROAD RACING SPEEDWAY SPRINT SUPERCROSS SUPERMOTO TRIALS HANDBOOK 2015 2015 HANDBOOK January 2015 All enquiries should be addressed to: The Auto-Cycle Union Ltd., ACU House, Wood Street, Rugby, Warwickshire CV21 2YX. Telephone: 01788 566400; Fax: 01788 573585 www.acu.org.uk [email protected] The contents of this Handbook are Copyright and must not be reproduced without written consent from the Auto-Cycle Union Ltd. The various regulations contained herein become effective as at 1st January 2014. This publication supersedes previous editions. The ACU is the internationally recognized National Governing Body for motorcycle sport in the British Isles (less Northern Ireland). Formed in 1903, the ACU has a long tradition in the world of motorcycle sport being a founder member of the World Governing Body, the Federation Internationale Motocyclisme (FIM). The ACU has a major role in furthering the interests of motorcycle sport on a global basis. Domestically, the ACU provides for all forms of motorcycle sport ranging from Road Racing to all disciplines of Off Road activity and has successfully organized world class events such as Moto GP, World Superbikes, the Isle of Man TT Races and the Motocross of Nations. The ACU aims to ensure that all people irrespective of their age, gender, disability, race, ethnic origin, creed, colour, social status or sexual orientation, have a genuine and equal opportunity to participate in motorcycle sport at levels in all roles. -

Passenger Information During Snow Disruption December 2010

Passenger information during snow disruption December 2010 A Rail passenger Information during snow disruption December 2010 Headline Findings 1. The National Rail Enquiries (NRE) website appears to have coped well with very high volumes 2. The online real time journey planner on the NRE website did not show correct information for some train operating companies (TOCs) 3. The online journey planners on TOC and third-party websites did not generally reflect the contingency timetables in operation 4. Tickets continued to be available for sale online for many trains that would not run 5. Station displays appear to have reflected formal contingency timetables, except for Southeastern 6. Station displays and online Live Departure Boards did not always keep pace with events 7. The NRE call centres appear to have provided good information, but queuing times of 11 or 12 minutes were common. 1 The National Rail Enquiries appears to have coped well with very high volumes We saw no evidence that the NRE website crashed or was slower than usual, despite a large spike in volume (Chris Scoggins reported that the volume on 2 December was twice the previous record peak on 7 January 2010). 2 The online real time journey planner on the NRE website did not show correct information for some train operating companies NRE had to advise passengers not to use the journey planner for enquiries about East Coast, Southeastern and South West Trains. This was a significant failure, with three scenarios: 2a Although the journey planner showed services from a contingency timetable for East Coast on 1 and 2 December, it also showed services from the base timetable that were no longer running. -

Regulation of Bus Services Bill PUBLIC CONSULTATION DOCUMENT

Regulation of Bus Services Bill PUBLIC CONSULTATION DOCUMENT CHARLIE GORDON MSP www.charliegordonmsp.com 2 Regulation of Bus Services Bill LIST OF CONTENTS Section 1 Introductory Summary PAGES 3-7 Section 2 Legislative Background PAGES 8-10 Section 3 Bus Operations PAGES 11-16 Section 4 Public Funding For Buses PAGES 17-18 Section 5 Bus Policy PAGES 19-23 Section 6 Free Bus Travel PAGES 24-28 Section 7 Bus Workers PAGES 29-30 Section 8 List of References PAGE 31 Section 9 Glossary PAGE 32 Section 10 Acknowledgements PAGE 33 Section 11 Charlie Gordon MSP – Biographical Notes PAGE 34 Section 12 Responding to this Proposal PAGES 35-39 www.charliegordonmsp.com 3 Section 1: Introductory Summary Buses are the most commonly used form of public transport in Scotland and provide a vital service. There has been a growth in bus patronage in six of the last seven years, reversing a longer-term decline. Some 482 million passenger journeys were made by bus in 2006/07 the highest figure in a decade. A total of 322m vehicle kilometres were covered by commercial services, 55m vehicle km by subsidised services and an unknown distance by community trans - port organisations. The Scottish Government and local authorities spent more than £ 250 million on support for bus services in 2006/07. But, despite this significant public investment, there is little regulation of how the bus industry used this money to improve services for travellers. Under exist - ing rules, councils only have powers to dictate timetables and fares in very lim - ited circumstances , and the Traffic Commissioner who acts as the UK Government ' s bus watchdog , tries to ensure that bus operators keep to regis - tered and advertised timetables and operate safe and roadworthy vehicles. -

Bus Operators Finding Aid

Falkirk Archives (Archon Code: GB558) FALKIRK ARCHIVES Records of Businesses Bus Operators Finding Aid Walter Alexander & Sons Ltd Walter Alexander began running buses in the Falkirk area in 1914. The first Charabanc New Belhaven (convertible to lorry) arrived in the spring of 1913 and another Belhaven (second hand) also convertible to lorry, was acquired in either 1915 or 1916. During the First World War the company was limited to private hires and haulage and a service was run on Saturdays and Sundays between Falkirk and Bonnybridge. Another charabanc, a W.D. Leyland, was introduced to replace one of the Belhaven's in 1919. Walter Alexander took a private party to John O'Groats in the summer of 1919 and it is supposed to be the first charabanc to have arrived there. The company of W Alexander & Sons Ltd was formed in 1924. The routes expanded to include Stirling-Glasgow in 1925 and Perth - Glasgow in 1926. In 1927 the company acquired Elliott & Begg of Perth. In 1929 W Alexander & Sons were acquired as a subsidiary of SMT (The Scottish Motor Traction Co) and became the area company for most of the east of Scotland north of the Forth. Other bus companies acquired by SMT as subsidiaries to W Alexander & Sons included The Pitlochry Motor Co, Simpson's & Forresters (based in Fife) and the Scottish General Omnibus Group (based in Falkirk). The Scottish General Omnibus Group included Dunsire of Falkirk, the bus section of Wemyss Tramways, Penman of Bannockburn, the bus section of Dunfermline Tramways, the General Motor Carrying Co of Kirkcaldy and the Northern Omnibus Services of Elgin. -

2021 Book News Welcome to Our 2021 Book News

2021 Book News Welcome to our 2021 Book News. As we come towards the end of a very strange year we hope that you’ve managed to get this far relatively unscathed. It’s been a very challenging time for us all and we’re just relieved that, so far, we’re mostly all in one piece. While we were closed over lockdown, Mark took on the challenge of digitalising some of Venture’s back catalogue producing over 20 downloadable books of some of our most popular titles. Thanks to the kind donations of our customers we managed to raise over £3000 for The Christie which was then matched pound for pound by a very good friend taking the total to almost £7000. There is still time to donate and download these books, just click on the downloads page on our website for the full list. We’re still operating with reduced numbers in the building at any one time. We’ve re-organised our schedules for packers and office staff to enable us to get orders out as fast as we can, but we’re also relying on carriers and suppliers. Many of the publishers whose titles we stock are small societies or one-man operations so please be aware of the longer lead times when placing orders for Christmas presents. The last posting dates for Christmas are listed on page 63 along with all the updates in light of the current Covid situation and also the impending Brexit deadline. In particular, please note the change to our order and payment processing which was introduced on 1st July 2020. -

Public Passenger Vehicles Act 1981

Status: Point in time view as at 03/01/1995. This version of this Act contains provisions that are not valid for this point in time. Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to Public Passenger Vehicles Act 1981. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) Public Passenger Vehicles Act 1981 1981 CHAPTER 14 An Act to consolidate certain enactments relating to public passenger vehicles. [15th April 1981] Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Act modified in part by virtue of S.I. 1980/1460, regs. 4–6 (as amended by S.I. 1981/462, regs. 2–4) and Interpretation Act 1978 (c. 30, SIF 115:1), ss. 17(2)(a), 23(3) C2 Act modified by S.I. 1984/748, regs. 4(2), 5(2), 6(2), 7(2), 9(2), 10(2), 11(2), 12(2), Sch. 2 C3 Act excluded (E.W.) by London Regional Transport Act 1984 (c. 32, SIF 126), s. 44(1) C4 Act excluded (E.W.) by Transport Act 1985 (c. 67, SIF 126), s. 11(1)(a) C5 Act amended by S.I. 1986/1628, reg. 5(2)(3) C6 Act: definition applied (E.W.) by Water Industry Act 1991 (c. 56, SIF 130 ), ss. 76(5)(a), 223(2) (with ss. 82(3), 186(1), 222(1), Sch. 13 paras.1, 2, Sch. 14 para. 6) C7 Definition of "PSV testing station" applied (1.7.1992) by Road Traffic Act 1988 (c. -

October 2020 Room 212 Used Lockdown Productively to Have Show for the Glos Rd Central a Clear out and Create a New Gallery Space on Community

Keep Me Keep Me I'm useful I'm useful Bishopstonincluding Ashley Down, Horfield & St. Andrews Bishopstonincluding Ashley Down, Horfield & St. Andrews Mattersissue 141, Oct 2020Mattersissue 141, Oct 2020 The heart of yoga in Bristol 0117 924 3330 Marking the 125th Yogawest is open againMarking with social the 125th anniversary of distancing in place: bookanniversary your class of St Andrews Park online before you come.St Andrews Park Booking now for new Newcomer, Beginner and Teenager classes! F F F FFFFFF FFFFFFFFF Find us just off the Gloucester Road, walk up lane FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF FFFF FFFF FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF Find Bishopston Matters on Facebook FollowFind Bishopston@bishmatters Matters on Twitter on Facebook Follow @bishmatters on Twitter BS7Gym Flyer Feb 2020 FINAL.pdf 1 10/02/2020 14:08 Dear Readers... As you can see from the front cover, My family and I have loved visiting Stoke 2020 marks 125 years since our wonderful Park over recent months. I hope you enjoy park opened. The pandemic may have put my introduction to this special place and are the party plans on hold until next spring inspired to go and explore for yourself. but to celebrate this anniversary, the It was great to hear from local resident Friends of St Andrew’s Park have created John Hardy, who has made the best of the a commemorative calendar filled with current situation and embarked on an epic historical postcards. The Park has always cycle from his home in Horfield to Scotland, been a special place for me and my family raising funds for charity Crisis on his way.