Remembering the Reformation John Calvin 29 October 2017 Michael

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hot Off the Press!

New Logo Many of you noticed last week in the bulletin that there SEPT 2017 is a new logo for CHPC. This is the first fruit of the HotHot OffOff thethe Press!Press! 9/17/1712/1/13 Identity Team which is itself part of the larger Regen- eration campaign. The team formed at the beginning of 2017 and worked with Brownstone Design to come up with a new logo for our church. 2017 — the 500th Anniversary of the of Scotland. England again stood with the reformers. France sided with Catholic leaders including the regent Queen, Mary PROTESTANT REFORMATION. 9TH IN A SERIES. of Guise (Mary Queen of Scots). In the center of the block-long ‘Reformation Wall’ in Geneva Finally in 1560-1561, the Scottish Parliament met to settle the Switzerland stand four 16 foot tall statues: William Farel (1489-1565); 1 John Calvin (1509–1564); John Knox (1513–1572) and Theodore dispute. They approved the Scots Confession. It abolished Beza (1519–1605). Knox’s amazing life was covered in two articles. the rule of the Pope, condemned all practice and doctrine con- trary to the Reformed Faith, and outlawed the celebration of the mass. One result was that for nearly 400 years educators THE MAN WHO CHANGED SCOTLAND in Scotland were required to affi rm the Scots Confession and ...AND THE WORLD PART 2 later the Westminister Confession. God’s Word became the BY ELDER RICK SCHATZ, EVANGELICAL COMMUNITY CHURCH standard for schools...and it changed Scotland and the world. In the previous article on Knox, Rev Tom Sweets noted: “Some- The controversy between the Reformed Faith and Roman thing dramatic happened in Scotland.. -

“Here I Stand” — the Reformation in Germany And

Here I Stand The Reformation in Germany and Switzerland Donald E. Knebel January 22, 2017 Slide 1 1. Later this year will be the 500th anniversary of the activities of Martin Luther that gave rise to what became the Protestant Reformation. 2. Today, we will look at those activities and what followed in Germany and Switzerland until about 1555. 3. We will pay particular attention to Luther, but will also talk about other leaders of the Reformation, including Zwingli and Calvin. Slide 2 1. By 1500, the Renaissance was well underway in Italy and the Church was taking advantage of the extraordinary artistic talent coming out of Florence. 2. In 1499, a 24-year old Michelangelo had completed his famous Pietà, commissioned by a French cardinal for his burial chapel. Slide 3 1. In 1506, the Church began rebuilding St. Peter’s Basilica into the magnificent structure it is today. 2. To help pay for such masterpieces, the Church had become a huge commercial enterprise, needing a lot of money. 3. In 1476, Pope Sixtus IV had created a new market for indulgences by “permit[ing] the living to buy and apply indulgences to deceased loved ones assumed to be suffering in purgatory for unrepented sins.” Ozment, The Age of Reform: 1250-1550 at 217. 4. By the time Leo X became Pope in 1513, “it is estimated that there were some two thousand marketable Church jobs, which were literally sold over the counter at the Vatican; even a cardinal’s hat might go to the highest bidder.” Bokenkotter, A Concise History of the Catholic Church at 198. -

Rhine River Reformation Cruise

Rhine River Reformation Cruise JULY 9 – 23, 2018 Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary, with president Dr. Joel R. Beeke, invites you to travel through Europe by deluxe motorcoach and luxurious river cruise ship. We’ll be stopping for day visits at various old cities, many of which house famous sites of pre- Reformation, Reformation, and post-Reformation history. Our tour also features Dordrecht, to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the famous Synod of Dordrecht (Dort). Dr. Beeke, together with Reformation lecturers Dr. Ian Hamilton and David Woollin, will provide fascinating historical and theological addresses and insights along the way, together with highly qualified local guides. Don’t miss this very special occasion! Dr. Joel R. Beeke is president and professor of systematic theology and homiletics at Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary, a pastor of the Heritage Reformed Congregation in Grand Rapids, Michigan, editor of Banner of Sovereign Grace Amsterdam Truth, and editorial director of Reformation Amersfoort Heritage Books. He has written and co- Kralingseveer Woudenberg authored ninety books, edited one hundred books, and contributed 2,500 articles to Dordrecht Reformed books, journals, periodicals, and encyclopedias. His PhD is in Reformation and Post-Reformation theology from Westminster Theological Seminary (Philadelphia). Cologne He is frequently called upon to lecture at seminaries and to speak Rhine at Reformed conferences around the world. He and his wife Mary Marburg have been blessed with three children and two grandchildren. Herborn Dr. Joel R. Beeke | 616-432-3403 | [email protected] Koblenz Cochem Rüdesheim Dr. Ian Hamilton was the minister of Cambridge Presbyterian Church, England, until July 2016. -

Protector's Pen July 2015

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION The Protector’s Pen Cromwell Day 2015 National Civil War Centre Reformation Wall, Geneva Exhibitions, Book & Play Reviews Vol 17 Issue 2 July 2015 The CROMWELL ASSOCIATION …..promoting our understanding of the 17th century CONTENTS Inside this issue 4 Chairman’s Little Note 3 Cromwell Day 4 Cromwell Association AGM, 2015 5 Samuel Pepys Exhibition 6 National Civil War Centre 7 Magna Carta Exhibition 9 CROMWELL DAY NATIONAL CIVIL WAR CENTRE Reformation Wall, Geneva 11 Play Review 12 Book Review 13 Publications, Exhibitions, Events 12 In the Press 15 Merchandise 16 SAMUEL PEPYS EXHIBITION MAGNA CARTA EXHIBITION GENEVA If you have not received an email from the Association in the last few months, please send your current email address to [email protected] headed ‘Cromwell Association email’, and provide your name and mailing address in the body of the email. The best email addresses for communication with the Association are that of the Chairman [email protected] and for membership and financial enquiries [email protected]. The email address on the website is not an efficient means for members to contact us. Front Cover : Statue of Cromwell outside Houses of President : Peter Gaunt Parliament Chairman : Patrick Little Treasurer : Geoffrey Bush (Courtesy of Membership Officer : Paul Robbins Maxine Forshaw) www.olivercromwell.org Vol 17 Issue 2 July 2015 2 The Cromwell Association is a registered charity. Reg No. : 1132954 The Protector’s Pen Chairman’s Little Note Members of the Cromwell Association at Basing House for the AGM, April 2015 Welcome to the summer issue of The Protector’s Pen. -

Calvinism and the Arts Susan Hardman Moore

T Calvinism and the Arts Susan Hardman Moore In 1540 Calvin wrote to a young student to praise his devotion to study, but also to deliver a warning: ‘Those who seek in scholarship nothing more than an honoured occupation with which to beguile the tedium of idleness I would compare to those who pass their lives looking at paintings.’ This spur-of-the-moment remark, committed to paper as Calvin settled down to answer letters (as he did everyday), is revealing. Calvin backed up his opinion that study for its own sake is pointless with an unfavourable reference to those ‘who pass their lives looking at paintings’.1 Calvin: austere, hostile to the arts? Calvinism: corrosive to human creativity and delight in beauty? Calvin’s reputation for austerity, some suggest, stems in part from his context in Geneva, where the strife- torn citizens were too hard pressed and poor to support patronage of the arts in the style of wealthy Basle, or of the kind Luther enjoyed in Wittenberg.2 To counter Calvin’s dour reputation, scholars highlight his affirmation of the arts: ‘I am not gripped by the superstition of thinking absolutely no images permissible […] sculpture and painting are gifts of God’;3 ‘among other things fit to recreate man and give him pleasure, music is either first or one of the principal […] we must value it as a gift of God’.4 Calvin’s writings also show appreciation of the splendours of Creation. In the natural world, God ‘shows his glory to us, whenever and wherever we cast our gaze’.5 For Calvin, God’s glorious gift of beauty shows – like his gifts of food and wine – how God gives not simply what is needed, but what will stir up ‘delight and good cheer’, ‘gladden the heart’.6 Calvin was in fact quite a bon vivant who enjoyed meals with friends and colleagues; he particularly liked fish, fresh from Lake Geneva. -

Visual Art, the Artist and Worship in the Reformed Tradition: a Theological Study

Visual Art, the Artist and Worship in the Reformed Tradition: A Theological Study submitted by Geraldine Jean Wheeler B.A. (University of Queensland, 1965), B.D. Hons. (Melbourne College of Divinity, 1970), M. Th. (University of Queensland, 1975), M. Ed. (University of Birmingham, UK, 1976) A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts and Science Faculty of Arts and Science Australian Catholic University Office of Research, Locked Bag 4115, Fitzroy, Victoria, 3065, Australia 30th May 2003 Statement of Sources This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgment in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. All research procedures reported in the thesis received the approval of the relevant Ethics Committee. Signature……………………………………………..Date……………………. ii Acknowledgments I wish to acknowledge with thanks the contribution made by the following people and institutions towards the writing of this thesis. I am very grateful to the Australian Catholic University for accepting the enrolment, which has allowed me to remain in my home in Queensland. I am also very grateful to staff members, Dr. Lindsay Farrell and Dr. Wendy Mayer, and to Rev. Dr. Ormond Rush of St. Paul’s Theological Seminary, for providing generous supervisory guidance from the perspectives of their different disciplines. -

William Farel – the Uncompromising Swiss Reformer of Geneva (1489 – 1565)

MARANATHA MESSENGER Weekly Newsletter of Private Circulation Only MARANATHA BIBLE-PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH 2 February 2014 “Present every man perfect in Christ Jesus” (Colossians 1:28) Address: 63 Cranwell Road, Singapore 509851 Tel: (65) 6545 8627 Fax: (65) 6546 7422 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.maranatha-bpc.com Sunday School: 9.45 am Sunday English / Chinese Worship Service: 10.45 am Sunday Chinese Worship Service: 7 pm Wednesday Prayer Meeting: 8.00 pm Pastor: Rev. Dr. Jack Sin (HP: 9116 0948) William Farel – The Uncompromising Swiss Reformer of Geneva (1489 – 1565) Introduction Hebrews11:32-34, ‘And what shall I more say? for the time would fail me to tell of Gedeon, and of Barak, and of Samson, and of Jephthae; of David also, and Samuel, and of the prophets:Who through faith subdued kingdoms, wrought righteousness, obtained promises, stopped the mouths of lions. Quenched the violence of fire, escaped the edge of the sword, out of weakness were made strong, waxed valiant in fight, turned to flight the armies of the aliens.’ There are men who have, by the will of God blazed a trail and changed the course of history for cites or even nations. Our recent trip to Geneva, Switzerland has given me a renewed interest in one man who made a lasting spiritual impact for Christ in this second largest city of Switzerland in the 16th century. His Background Guillaume Farel (1489 – 1565) was a spiritual game changer as we will say today who impacted his people by the powerful teaching of the Word and the expository preaching of the Gospel of Christ during the 16th century when many were still hostile to sound true religion being blinded by the deception of the medieval church. -

A Protestant Heritage Tour – John Wesley & John Calvin

A Protestant Heritage Tour – John Wesley & John Calvin 12 days / 10 nights John Wesley (1703—1791), a Christian theologian and one of the founders of the Methodist movement, rode 250,000 miles, gave away 30,000 pounds... and preached more than 40,000 sermons (Stephen Tomkins, biographer). John Calvin (1509—1564) an important French pastor at the time of the Protestant Reformation, left the Catholic Church around 1530 and fled to Switzerland where he established a Christian theology that would become known as Calvinism. As we follow the awe-inspiring trail of these two great reformers, John Wesley and John Calvin, separated as they were by about 200 years, we will not only thrill at the grandeur of several European cities and the beauty of the English, German and Swiss countryside, we will also gain an understanding of and deep appreciation for their convictions and courage. Day 1: Departure from the USA ___________________________________________ I am only an honest heathen...and yet, to be so employed of God! (From a letter John Wesley wrote to his brother at age 63). Our journey begins with an overnight flight with full meal/beverage service and in-flight entertainment to London, England. Day 2: Salisbury & Stonehenge ____________________________________________ [A]n inward impression on the soul of believers whereby the Spirit of God directly testifies to their spirit that they are the children of God (John Wesley’s definition of the witness of the Spirit). After meeting our tour manager, we’ll travel by motor coach through the beautiful English countryside to Bristol. En route we’ll stop to experience the mystery of Stonehenge, one of the most famous prehistoric monuments in the world. -

By Christ Alone

How C an I Be Right w ith God? © 2017 by R.C . Sproul Published by Reformation Trust Publishing A div ision of Ligonier Ministries 421 Ligonier C ourt, Sanford, F L 32771 Ligonier.org ReformationTrust.com Printed in C hina RR Donnelley 0001018 F irst edition, third printing ISBN 978-1-64289-061-7 (Paperback) ISBN 978-1-64289-089-1 (ePub) ISBN 978-1-64289-117-1 (Kindle) A ll rights reserv ed. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retriev al sy stem, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy , recording, or otherw ise—w ithout the prior w ritten permission of the publisher, Reformation Trust Publishing. The only exception is brief quotations in published rev iew s. C ov er design: Ligonier C reativ e Interior ty peset: Katherine Lloy d, The DESK A ll Scripture quotations are from the ESV ® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard V ersion®), copy right © 2001 by C rossw ay , a publishing ministry of Good New s Publishers. Used by permission. A ll rights reserv ed. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sproul, R.C . (Robert C harles), 1939-2017 author. Title: How can I be right w ith God? / by R.C . Sproul. Description: O rlando, F L: Reformation Trust Publishing, 2017. | Series: C rucial questions; No. 26 | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LC C N 2017023438 | ISBN 9781567698374 Subjects: LC SH: Justification (C hristian theology ) | Salv ation--C hristianity . | A ssurance (Theology ) C lassification: LC C BT764.3.S6695 2017 | DDC 234/.7--dc23 LC record av ailable at https://lccn.loc.gov /2017023438 This digital document has been produced by Nord C ompo. -

The Bulwark Magazine of the Scottish Reformation Society

The Bulwark Magazine of the Scottish Reformation Society JULY - SEPT 2017 // £2 July - September 2017 1 The Bulwark PROBLEMS CONFRONTING THE CHURCH Magazine of the Scottish Reformation Society The Magdalen Chapel 41 Cowgate, Edinburgh, EH1 1JR Tel: 0131 220 1450 9 Email: [email protected] www.scottishreformationsociety.org Registered charity: SC007755 Chairman Committee Members NEGLECT OF CHURCH HISTORY » Rev Dr S James Millar » Rev Maurice Roberts Vice-Chairman » Rev Kenneth Macdonald AND FORGETFULNESS OF GOD’S » Mr Allan McCulloch » Rev Alasdair Macleod Secretary MERCIES IN THE PAST » Rev Douglas Somerset » Mr Matthew Vogan Treasurer » Rev Andrew Coghill John J Murray This is the final article in a series by Mr Murray on “Problems confronting the Church”. CO-OPERATION OBJECTS OF THE SOCIETY In pursuance of its objects, the Society may co- (a) To propagate the evangelical Protestant faith operate with Churches and with other Societies and those principles held in common by those Churches and organisations adhering to The Triune God is the ultimate and the the Church and of the world, regarded as whose objects are in harmony with its own. the Reformation; eternal reality. He is the Creator and a whole, is but the evolution of the eternal sustainer of the whole universe and all purpose of that God who ‘worketh all Magazine Editor: Rev Douglas Somerset (b) To diffuse sound and Scriptural teaching on things therein. He is an intelligent, personal things after the purpose of his own will’. All literary contributions, books for review and the distinctive tenets of Protestantism and Being who has foreordained whatsoever Deep in the secrets of his own breast is hid papers, should be sent to: Roman Catholicism; comes to pass. -

What Is the Reformation ?

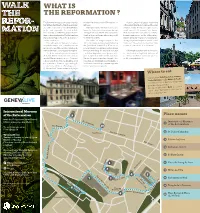

WHAT IS THE REFORMATION ? The Reformation was a 16th-century revolu- to take o with the arrival of John Calvin, in A second wave of refugees arrived in the tion within Christianity, of which Geneva was July 1536. 17th century, after the Revocation of the Edict one of the main centres. It saw individuals During the 1540s, Geneva became a safe of Nantes (1685). Geneva once again became as free and responsible for their beliefs. haven for Protestants from across Europe a safe haven for Protestants from France. People turned to the Bible for guidance rather eeing persecution. These men and women They boosted the industries that Geneva than to church authorities. The Reformation found in Geneva a home where they could became famous for in the 18th century: was a crucial stage between the Renaissance freely live their faith. watchmaking, banking and the manufacture and the modern era. The inux of refugees began in the of a type of printed or painted fabric called This walking tour will take you to 10 places mid- 16th century and rose sharply following “indienne”. They also consolidated the city’s of symbolic importance for the Reformation the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in stature as a centre for art and science. in Geneva, a period that left a deep mark on the 1572, an attempt to rid France of Protestants city’s architecture, economy and spirituality. by order of the king. The mainly French, but Following the adoption of the Reformation, The Reformation began in Germany in also Italian, English and even Spanish, refu- the intellectual and spiritual inuence of 1517 with Martin Luther. -

Business with God: the Life of John Calvin

Reformation & Modern Church History Lesson 8, page 1 Business with God: The Life of John Calvin A young Frenchman, a lawyer who was 30 years old, wrote these words in 1539, “We are not our own: let not our reason nor our will, therefore, sway our plans and deeds. We are not our own: let us, therefore, not set it as our goal to seek what is expedient for us according to the flesh. We are not our own: in so far as we can, let us, therefore, forget ourselves and all that is ours. Conversely, we are God’s: let us, therefore, live for Him and die for Him. We are God’s: let His wisdom and will, therefore, rule all our actions. We are God’s: let all the parts of our life, accordingly, strive toward Him as our only lawful goal.” That young man had recently been converted to the Protestant faith. He lived in the city of Strasbourg. His name was John Calvin. As we study the life of Calvin, let us remember those words from Calvin, “We are not our own. We are God’s.” I will begin with a prayer from Calvin. Calvin wrote many prayers, and the one I have chosen to use today is Calvin’s “Prayer for the Morning.” It was a prayer that he wrote for his people to use in their times of prayer in the morning. Let us join together in this prayer from Calvin. “My God, my Father and preserver, who of Thy goodness hast watched over me during the past night and brought me to this day, grant also that I may spend it wholly in the worship and service of Thy most holy deity.