The Logic of Vertical Density: Tall Buildings in the 21St Century City Kheir Al-Kodmany†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Building Evacuation-Simulation of Potential

R. JEVTIĆ RESIDENTIAL BUILDING EVACUATION-SIMULATION OF POTENTIAL Residential Building Evacuation-Simulation of Potential Evacuation Scenarios With Presence of Immobile Persons RADOJE B. JEVTIĆ, Electrotechnical school „Nikola Tesla“, Niš Professional paper UDC: 614.8.084 DOI: 10.5937/tehnika2006814J The increase in urban population leads to the lack of housing in cities. One of potential solutions for this problem is to build tall residential buildings. The height of this objects, in recent times, ranges from several tens of meters even to several hundreds of meters, while the number of residents ranges from several hundred even to several thousands. Although these objects have built related to modern standards and technologies, with usage of modern materials and machines, problems can happen. One of particularly complex and hard problem presents the evacuation of residents in case of some disaster. Problem is much more severe and complicated if there are people with disabilities or people with special needs in the building. The potential solution for this problem can be the usage of simulation software. This paper was written to show the usage of simulation software Pathfinder in calculation of evacuation times for different evacuation scenarios, without the presence of immobile occupants, with presence of immobile occupants in the percentage of 5 % from complete occupant’s number and with presence of immobile occupants in the percentage of 10 % from complete occupant’s number. Key words: evacuation, residential, immobile, scenario 1. INTRODUCTION The advancement of science, the usage of many new technics and materials has led to the advancement High residential buildings present the past, the in architecture, unthinkable before. -

Evaluating Skyscraper Design and Construction Technologies on an International Basis

EVALUATING SKYSCRAPER DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION TECHNOLOGIES ON AN INTERNATIONAL BASIS by Saad Allah Fathy Abo Moslim B.Sc., Mansoura University, Egypt, 1984 M.Eng., The University of British Columbia, Canada, 2000 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Civil Engineering) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2017 © Saad Allah Fathy Abo Moslim, 2017 Abstract Design and construction functions of skyscrapers tend to draw from the best practices and technologies available worldwide in order to meet their development, design, construction, and performance challenges. Given the availability of many alternative solutions for different facets of a building’s design and construction systems, the need exists for an evaluation framework that is comprehensive in scope, transparent as to the basis for decisions made, reliable in result, and practical in application. Findings from the literature reviewed combined with a deep understanding of the evaluation process of skyscraper systems were used to identify the components and their properties of such a framework, with emphasis on selection of categories, perspectives, criteria, and sub-criteria, completeness of these categories and perspectives, and clarity in the language, expression and level of detail used. The developed framework divided the evaluation process for candidate solutions into the application of three integrated filters. The first filter screens alternative solutions using two-comprehensive checklists of stakeholder acceptance and local feasibility criteria/sub-criteria on a pass-fail basis to eliminate the solutions that do not fit with local cultural norms, delivery capabilities, etc. The second filter treats criteria related to design, quality, production, logistics, installation, and in-use perspectives for assessing the technical performance of the first filter survivors in order to rank them. -

PDF Download First Term at Tall Towers Kindle

FIRST TERM AT TALL TOWERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lou Kuenzler | 192 pages | 03 Apr 2014 | Scholastic | 9781407136288 | English | London, United Kingdom First Term at Tall Towers, Kids Online Book Vlogger & Reviews - The KRiB - The KRiB TV Retrieved 5 October Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Archived from the original on 20 August Retrieved 30 August Retrieved 26 July Cable News Network. Archived from the original on 1 March Retrieved 1 March The Daily Telegraph. Tobu Railway Co. Retrieved 8 March Skyscraper Center. Retrieved 15 October Retrieved Retrieved 27 March Retrieved 4 April Retrieved 27 December Palawan News. Retrieved 11 April Retrieved 25 October Tallest buildings and structures. History Skyscraper Storey. British Empire and Commonwealth European Union. Commonwealth of Nations. Additionally guyed tower Air traffic obstacle All buildings and structures Antenna height considerations Architectural engineering Construction Early skyscrapers Height restriction laws Groundscraper Oil platform Partially guyed tower Tower block. Italics indicate structures under construction. Petronius m Baldpate Platform Tallest structures Tallest buildings and structures Tallest freestanding structures. Categories : Towers Lists of tallest structures Construction records. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read Edit View history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. Wikimedia Commons. Tallest tower in the world , second-tallest freestanding structure in the world after the Burj Khalifa. Tallest freestanding structure in the world —, tallest in the western hemisphere. Tallest in South East Asia. Tianjin Radio and Television Tower. Central Radio and TV Tower. Liberation Tower. Riga Radio and TV Tower. Berliner Fernsehturm. Sri Lanka. Stratosphere Tower. United States. Tallest observation tower in the United States. -

Emaar Properties (PJSC) Initiating Coverage UAE Real Estate 23 Sep

Emaar Initiating Properties (PJSC ) Coverage UAE 23 Sep 2012 Real Estate Price Target We initiate coverag e of EMAAR PROPERTIES, the largest real estate developer in Current Mkt.Price (AED) 3.58 GCC with a BUY rating and target price of AED 4.15 per share. The recent uptick in Target Price (AED) 4.1 5 investor sentiment towards Dubai real estate combined with Emaar’s traction in de- Upside / (Downside), % +15.9 risking its revenue sources from purely property development to mix of recurring revenue stream is in our opinion strong positives to narrowing the gap between Est. Dividend Yield, % +2.8 Emaar’s current market value and its estimated fair value Est. Total Return, % +18.7 Stock Information Dubai Real Estate Stabilizing DFM Code EMAAR Property and rentals in Dubai seem to have bottomed out since Q4’2011. Significant Bloomberg Code EMAAR DH Equity correction in prices since Q1’2009 has set a stage of attractive rental yields compared 3-M Avg. daily volume (‘000s)) 14,204 to other cosmopolitan cities in the region. Emaar remains the torch bearer of Dubai Shares outstanding (millions) 6,091 Real Estate and in many ways emblematic of what brand ‘Dubai’ stands for Market Cap. (AED millions) 21, 623 Emaar de-risking strategy is gaining traction 52W High (AED) 3.63 (19Sep 12) Emaar’s portfolio of recurring revenue assets now contributes roughly 40% of top-line 52W Low (AED) 2.33 (15Jan12) revenues compared to c.10% in 2008. Rental and Hospitality segment provide Price Performance revenue visibility; impart balance sheet liquidity and reduce overall business risk. -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

News Brief 47 Sunday, 19 November 2017

ASSET MANAGEMENT SALES LEASING VALUATION & ADVISORY SALES MANAGEMENT OWNER ASSOCIATION NEWS BRIEF 47 SUNDAY, 19 NOVEMBER 2017 RESEARCH DEPARTMENT DUBAI | ABU DHABI | AL AIN | SHARJAH | JORDAN IN THE MIDDLE EAST FOR 30 YEARS © Asteco Property Management, 2017 asteco.com | astecoreports.com ASSET MANAGEMENT SALES LEASING VALUATION & ADVISORY SALES MANAGEMENT OWNER ASSOCIATION REAL ESTATE NEWS UAE / GCC QATAR FACES WORST DECLINE IN GCC REAL ESTATE SECTOR DSI REPORTS DH359M LOSS IN THIRD QUARTER A CHAIN THAT LIBERATES THE AFFORDABILITY ANGLE: A CONSUMER’S VIEW UNION PROPERTIES POSTS LOSS ON SUBSIDIARY CLOSURE RULES TIGHTENED FOR OFF-PLAN PROPERTY BUYERS IN DUBAI 'MY MOULDY APARTMENT IS MAKING ME SICK BUT THE AGENCY IS REFUSING TO CLEAN IT UP' STRUGGLING QATARI DEVELOPER SHED JOBS AMID SLUMP JOB VACANCIES RISE ACROSS MIDDLE EAST DUBAI CLASSIFICATION OF BUILDINGS IN DUBAI’S OLDER AREAS IN FINAL STRETCH THE LANGHAM EXPERIENCE MAKING SENSE OF A SLOW MARKET FROM HUMBLE ABRA STEPS TO SKY-HIGH ICONS A FURTHER 163,000 HOMES IN THE PIPELINE FOR DUBAI DOMESTIC SALES GAINS BOOST EMAAR’S NET PROFIT A PRIMER ON DUBAI RENTAL INDEX CALCULATIONS EMAAR DEVELOPMENT LPO RAISES DH4.8 BILLION IN LARGEST DUBAI LISTING IN THREE YEARS DH30M DUBAI APARTMENT COULD BE BUSINESS BAY'S FINEST EMAAR THIRD QUARTER NET PROFIT SOARS 32%, BEATS ANALYSTS' FORECASTS WASL LAUNCHES 3RD TOWER FOR SALE AT PARK GATE RESIDENCES DAMAC LAUNCHES VILLAS FOR DH2.5 MILLION DUBAI HOSPITALITY SECTOR TO SEE ADDITION OF 29,200 KEYS ABU DHABI HOME HUNTING ON THE YAS ISLAND ALDAR RECORDS DH601M -

Almas Tower 1 Almas Tower

Almas Tower 1 Almas Tower Almas Tower ﺑﺮﺝ ﺍﻟﻤﺎﺱ The Almas Tower General information Status Complete Type Commercial Location Dubai, United Arab Emirates Coordinates 25°04′08.25″N 55°08′28.34″E Construction started 2005 Completed 2008 Opening 2009 Height [1] Architectural 360 m (1,181 ft) [1] Top floor 279.3 m (916 ft) Technical details [1] Floor count 74 (68 above ground, 5 basement floors) [1] Floor area 160,000 m2 (1,700,000 sq ft) [1] Lifts/elevators 35 Design and construction Owner Dubai Multi Commodities Centre [1] Architect Atkins Middle East [1] Developer Nakheel Properties [1] Main contractor Taisei Corporation Almas Tower 2 Diamond Tower) is a supertall skyscraper in JLT Free Zone Dubai, United Arab ﺑﺮﺝ ﺍﻟﻤﺎﺱ :Almas Tower (Arabic Emirates. Construction of the office building began in early 2005 and was completed in 2009 with the installation of some remaining cladding panels at the top of the tower. The building topped out at 360 m (1,180 ft) in 2008, becoming the third-tallest building in Dubai, after Emirates Park Towers and Burj Khalifa. Almas Tower has 74 floors, 70 of which are commercial alongside four service floors. The tower is located on its own artificial island in the centre of the Jumeirah Lakes Towers Free Zone scheme, the tallest of all the buildings on the development when completed. It was designed by Atkins Middle East, who designed most of the JLT Free Zone complex. The tower is being constructed by the Taisei Corporation of Japan in a joint venture with ACC (Arabian Construction Co.) who were awarded the contract by Nakheel Properties on 16 July 2005.[2] Dubai Multi Commodities Centre (DMCC), the owner of the tower, was the first to move in. -

Desired 02 Series | New on the Market | Dream Unit

SELLING @ AED2.4M Desired 02 Series | New On The Market | Dream Unit *This property is subject to availability and the price is subject to change. Size may be approximate and images may be genereic. RESIDENTIAL FOR SALE Type Apartment Built-up Area 2,980 sqft Location Dubai Marina Bedrooms 3 Bed Property 23 Marina Bathrooms 4 Bath RERA Permit 7154082610 Parking 2 Car Park Agency Fee - Transfer Fee - Entered Date Nov 28, 2020 03:10 am Updated Date May 29, 2021 05:05 am Ref#:GMR-10936 TETIANA BARANETSKA [email protected] Client Manager +971 55 866 5538 BRN 46616 Detroit House, Motor City, Office 205, PO Box 644919, Dubai, United Arab Emirates ORN 16805 | DED License 745304 | www.goldmark.ae [email protected] | Tel: +971 4 451 1886 | Fax: +971 4 451 1581 Gold Mark Real Estate is delighted to offer for rent this rare modern high-end 3 bedroom + study apartment in the fantastic 23Marina Building, Dubai Marina Property Details: - Selling Price: 2,400,000 AED - BUA: 2980 Sq Ft - Sea, Media Cty And Golf Course View - 3 Bedrooms - 4 Bathrooms - Study Room - Modern And Bright - Unfurnished Amenities: - 24-hour Front Desk - 24-hour Security - Aerobics Room - Built in white goods - Business Center - CCTV Cameras - Concierge - Gym / Health Club - High-end Lobby - Indoor Pool - Jogging/Bicycling tracks - Key card security access - Outdoor Pool - Sauna 90 storey high-end residential building rising prominently in the Dubai Marina community. 23 Marina is one of the tallest buildings in Dubai. It is also claimed by the developer to be among the tallest residential buildings in the world. -

EVERSENDAI CORPORATION BERHAD EVERSENDAI ENGINEERING FZE EVERSENDAI ENGINEERING LLC EVERSENDAI Offshore SDN BHD Plot No

Towering – Powering – Energising – Innovating Moving to New Frontiers MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN & GROUP MANAGING DIRECTOR’s MESSAGE TAN SRI A.K. NATHAN Moving To New Frontiers The history of Eversendai goes back to 1984 and As we move to new frontiers, we are certain we after three decades of unparalleled experience, will be able to provide our clients the certainty and engineering, technical expertise and a strong network comfort of knowing that their projects are in capable across various countries, we are recognised as a and experienced hands. These developments will leading global organisation in undertaking turnkey complement our vision, mission and core values and contracts; delivering highly complex projects with simultaneously allow us to remain one of the most innovative construction methodologies for high rise successful organisations in the Asian and Middle buildings, power & petrochemical plants as well as Eastern Region and beyond with corresponding composite and reinforced concrete building structures efficiency and reliability. in the Asian and Middle Eastern regions. The successful and timely completion of our projects We have a dedicated workforce of over 10,000 accompanied by soaring innovation, creativity and people and an impressive portfolio of more than 290 our aspiration to move to new frontiers have been the accomplished projects in over 14 different countries key drivers for achieving continuous growth through with 5 steel fabrication factories located in Malaysia, the years and we remain committed to these values. Dubai, Sharjah, Qatar and India, with an annual This stamps our firm intent to dominate the various capacity of 150,000 tonnes. With our state-of-the-art industries which we are involved in and also marks steel fabrication factories, we have constructed some the next phase in our development to be amongst the of the world’s most iconic landmark structures. -

IBIS Deira City Center / IBIS Al Rigga Hotel / IBIS – WTC / IBIS

Hotels Avail for Transportation Central Dubai 2 Star Hotel: IBIS Deira City Center / IBIS Al Rigga Hotel / IBIS – WTC / IBIS – AL Barsha / Holiday Inn Express Airport hotel / Holiday Inn Express SAFA park / Holiday Inn Express Jumeirah 3 Star Hotel: Arabian Park Hotel / London Crown Hotel / City max Hotel – Bur Dubai / City max hotel -Al Basha / Howard Johnson Hotel / Admiral Plaza 4 Star Hotel: Al Jawhra Gardend / Al Kaleej Palace Hotel / Arabian Courtyard Hotel / Riviera Hotel / Sheraton Deira hotel / Ascot Hotel / Royal Ascot hotel / Traders hotel / Majestic Hotel / Four point Sheraton –Bur Dubai / Four points Sheraton – Down Town / Four point Sheraton Sheikh Zayed Hotel / Radisson BLU Downtown Hotel / Radisson BLU Deira creek hotel / Rose Rayhaan by Rotana / Towers Rotana Hotel / Burjuman Rotana Hotel / AL Manzil Down Town / Vida Downtown hotel / Avari Hotel / Avenue Hotel / Carlton Towers hotel / City Season hotel / Coral Deira Hotel /Cosmopolitan Hotel /Double Tree by Hilton Hotel & Residence Al barsha / Emirates Concorde Hotel /Emirates Grand Hotel /Flora Grand Hotel / Five Continent Cassells Al Basha / Fortune Boutique Hotel / Holiday Inn –Bur Dubai / Holiday Inn –Al Basha / Holiday Inn Downtown / Hyatt place Hotel / Landmark hotel /Marco polo Hotel / Novotel Deira City Center / Novotel WTC / Novotel Al Basha hotel / Ramada Chelsea Hotel / Ramada Deira hotel / Mercure Gold Hotel / Millennium Airport Hotel Dubai / Barjeel Guests House / Orient Guests House, etc. 5 Star Hotel: Armani Dubai / Hyatt Regency Hotel / Grand Hyatt hotel -

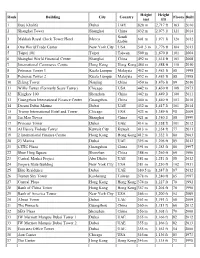

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

Print Version.Indd

Eindhoven University of Technology MASTER Undergroundscraper from ant nests to architecture Liu, M. Award date: 2015 Link to publication Disclaimer This document contains a student thesis (bachelor's or master's), as authored by a student at Eindhoven University of Technology. Student theses are made available in the TU/e repository upon obtaining the required degree. The grade received is not published on the document as presented in the repository. The required complexity or quality of research of student theses may vary by program, and the required minimum study period may vary in duration. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain UNDERGROUNDSCRAPER from ant nests to architecture Mo Liu Undergroundscraper Graduation project Digital Architecture January 2015 Student: M. (Mo) Liu 0827301 ([email protected]) Tutor: prof.dr.ir. B. (Bauke) de Vries ir. M. (Maarten) H.P.M. Willems drs. J. (Johan) G.A. van Zoest Eindhoven University of Technology The Department of the Built Environment Architecture Design & Decision support systems UNDERGROUNDSCRAPER b ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report is the result of the graduation pro- ey Heijkens, Guido le Pair, Marius Lazauskas, ject, Digital Architecture, in the Department of Arjan Kalfsbeek, Sebastiaan van Alebeek, Tom the Built Environment of Eindhoven University of Steegh and Maaike Bron.