Masquerading Mothers and False Fathers in Ancient Indian Mythology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought 1

The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought 1 The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought Department Website: http://socialthought.uchicago.edu Chair • Robert Pippin Professors • Lorraine Daston • Wendy Doniger • Joel Isaac • Hans Joas • Gabriel Lear • Jonathan Lear • Jonathan Levy • Jean Luc Marion • Heinrich Meier • Glenn W. Most • David Nirenberg • Thomas Pavel • Mark Payne • Robert B. Pippin • Jennifer Pitts • Andrei Pop • Haun Saussy • Laura Slatkin • Nathan Tarcov • Rosanna Warren • David Wellbery Emeriti • Wendy Doniger • Leon Kass • Joel Kraemer • Ralph Lerner • James M. Redfield • David Tracy About the Committee The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought was established as a degree granting body in 1941 by the historian John U. Nef (1899-1988), with the assistance of the economist Frank Knight, the anthropologist Robert Redfield, and Robert M. Hutchins, then President of the University. The Committee is a group of diverse scholars sharing a common concern for the unity of the human sciences. Their premises were that the serious study of any academic topic, or of any philosophical or literary work, is best prepared for by a wide and deep acquaintance with the fundamental issues presupposed in all such studies, that students should learn about these issues by acquainting themselves with a select number of classic ancient and modern texts in an inter- disciplinary atmosphere, and should only then concentrate on a specific dissertation topic. It accepts qualified graduate students seeking to pursue their particular studies within this broader context, and aims both to teach precision of scholarship and to foster awareness of the permanent questions at the origin of all learned inquiry. -

Destroying Krishna Imagery. What Are the Limits of Academic and Artistic Freedom? Maruška Svašek

Destroying Krishna Imagery. What are the Limits of Academic and Artistic Freedom? Maruška Svašek [ f i g . 1 ] Pramod Pathak: Wendy’s Unhistory making History, screenshot A photograph published in by Organiser, a weekly magazine based in New Delhi, shows a group of Indian demonstrators holding up various placards. »Don’t insult Hindu Lords« is printed on one of them; »Stop Prejudice Hate Talk Discriminating against Hindus« and »Abuse is not intelligent discourse« are written on others. Another placard addresses the target of the demonstra- tion: »Wendy Doniger Please don’t insult our Hindu Lords.« (Fig. ). An Internet search for »Wendy Doniger« leads to the other side of the globe, to the prestigious University of Chicago Divinity School. The Uni- versity website states that Professor Doniger specializes in Hinduism and Maruška Svašek - 9783846763452 Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 01:19:58AM via free access [ f i g . 2 ] Wendy Doniger’s home page on the University of Chicago’s website, screenshot mythology, has published over forty books on related topics in these fields, and received her postgraduate degrees from Harvard University and the Uni- versity of Oxford. In Chicago, Doniger holds the position of Mircea Eliade Distinguished Service Professor of the History of Religions and is associated with the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations and to the Committee on Social Thought (Fig. ). Clearly, she is a highly successful, inter- nationally renowned scholar who is considered an expert in her field. So why the accusations of blasphemy and prejudice? What compelled a group of Hindus to gather and protest against her? Maruška Svašek - 9783846763452 Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 01:19:58AM via free access In Organiser, this photograph was used to illustrate an article by Pramod Pathak, a Vedic scholar based in Goa, entitled »Wendy’s unhistory making history.« The piece was highly critical of Doniger’s latest book, The Hindus. -

Annual Report 2020 1

ACLS Annual Report 2020 1 AMERICAN COUNCIL OF LEARNED SOCIETIES Annual Report 2020 2 ACLS Annual Report 2020 Table of Contents Mission and Purpose 1 Message from the President 2 Who We Are 6 Year in Review 12 President’s Report to the Council 18 What We Do 23 Supporting Our Work 70 Financial Statements 84 ACLS Annual Report 2020 1 Mission and Purpose The American Council of Learned Societies supports the creation and circulation of knowledge that advances understanding of humanity and human endeavors in the past, present, and future, with a view toward improving human experience. SUPPORT CONNECT AMPLIFY RENEW We support humanistic knowledge by making resources available to scholars and by strengthening the infrastructure for scholarship at the level of the individual scholar, the department, the institution, the learned society, and the national and international network. We work in collaboration with member societies, institutions of higher education, scholars, students, foundations, and the public. We seek out and support new and emerging organizations that share our mission. We commit to expanding the forms, content, and flow of scholarly knowledge because we value diversity of identity and experience, the free play of intellectual curiosity, and the spirit of exploration—and above all, because we view humanistic understanding as crucially necessary to prototyping better futures for humanity. It is a public good that should serve the interests of a diverse public. We see humanistic knowledge in paradoxical circumstances: at once central to human flourishing while also fighting for greater recognition in the public eye and, increasingly, in institutions of higher education. -

Letter from the Dean

CIRCA News from the University of Chicago Divinity School AS YOU MAY HAVE NOTICED, THE RECENT UPDATE TO THE DESIGN OF THE Divinity School’s website includes a “virtual” faculty bookcase that loads when you click on the “Faculty” tab. It is indeed (as I have been asked) meant to replicate online the glass fronted wooden bookcase of “Recent Faculty Publications” that is the focal point for anyone entering the Swift Hall lobby from the main quadrangle, the hearth of the Divinity School. Faculty research and publications that which an historian is and is not a diagnos- shape their fields of inquiry remain at the tician of her own age were keen in the heart of what the School is about—its work, discussion of Schreiner’s book, Are You purpose, values, fundamental significance Alone Wise? Debates about Certainty in the and impact. Letter Early Modern Era, even as in conversation One of the ways that this is enshrined on Kevin Hector’s Theology without Meta- in the life of the Divinity School is a long- physics: God, Language, and the Spirit of standing tradition of the Dean’s Forum, a from the Recognition and Kristine Culp’s Vulnerability conversation at a Wednesday lunch in the and Glory: A Theological Account, studies Common Room (immediately behind the of theological language, referentiality and bookcase in the foyer, a room that contains Dean metaphysics and the theology of suffering, an actual hearth). Each Dean’s Forum focuses respectively, the measured responsibilities on a single recent faculty book or other to traditions and voices both past and publication; the usual format includes a present were pressed and engaged. -

RELIGIOUS STUDIES 412 JOURNEY and ILLUMINATION: JEWISH and HINDU MYSTICAL EXPRESSIONS

Department of Religious Studies Miriam Dean-Otting Miriam Dean-Otting PBX 5655 Ascension 124 [email protected] RELIGIOUS STUDIES 412 JOURNEY and ILLUMINATION: JEWISH AND HINDU MYSTICAL EXPRESSIONS Office Hours and Consultation For brief consultations, please see me before or after class. I am also available for longer meetings during my office hours. E-mail is the least preferred form of communication and should be used judiciously. If you have a physical, psychological, medical or learning disability that may affect your ability to carry out assigned course work, I urge you to contact the Office of Disability Services at 5453. The Coordinator of Disability Services, Erin Salva ([email protected]) will review your concerns and determine, with you, what accommodations are appropriate. After your meeting with Erin Salva, please see me to discuss accommodations and learning needs. I. Course Description This seminar offers a comparative approach to the study of mysticism with a focus on Hinduism and Judaism. In the course of our reading and study we will encounter concepts of alienation and longing, night, sleep, dream, dialectics of life and death, meditation and ecstasy, excursion and return, and the mystical landscape of symbol, myth, metaphor, allegory, and phantasmagoria. II. Requirements and Grading A. Regular attendance (no more than one unexcused absence will be accepted); timely completion of reading assignments and active participation in seminar discussions. (20`%) B. Writing Assignments All writing is due on the date announced, or, in the case of short response papers, on the day the reading is discussed. Missed due dates on longer pieces will result in grade penalties unless properly excused. -

REL. 324: the Hindu Vision

Prof. Joseph Molleur Prall House 101 [email protected] Office Phone: 895-4237 REL. 324: The Hindu Vision Aim of the Course The main focus of the course will be the attempt to understand the central components of the Hindu worldview, by a careful reading of some of the tradition’s classic texts. This will include a study of such things as creation myths, the vedic gods and goddesses, karma, reincarnation, ways of liberation, the relation of the individual Self to the universal Self, divine descent, dharma, caste, and the place and role of women. The course will conclude by reading portions of the autobiography of Mohandas K. Gandhi, to give an indication of how the ancient ideas and customs studied earlier in the course have influenced and inspired modern adherents of Hinduism. Educational Priorities and Outcomes 1. Students will acquire, integrate, and apply knowledge relating to multiple expressions of the Hindu religious tradition. 2. Students will read and analyze challenging texts, speak clearly and listen actively as we discuss those texts, and write essays explaining their understanding and interpretation of those texts. 3. Students will connect with diverse ideas and with people whose experiences differ from their own as we explore how Hinduism has been understood and practiced in India and South Africa over the course of many centuries. 4. Students will respect the ways spiritual well-being may contribute to a balanced life by learning about Hindu practices of meditation and devotion. This course supports the Educational Priorities and Outcomes of Cornell College with emphases on knowledge, communication, intercultural literacy, and well-being. -

SPRING 2013 COURSE DESCRIPTIONS (2-7-13) Complete and Up-To-Date Course Information Is Available on Thehub

SPRING 2013 COURSE DESCRIPTIONS (2-7-13) Complete and up-to-date course information is available on TheHub COGNITIVE SCIENCE (CS) CS-0108-1 DR Distribution Area: MBI Introduction to Philosophy Jonathan Westphal This course is an introduction to philosophy concentrating on the skills necessary to evaluate philosophical claims about minds, brains and information. Topics will be chosen from the following: language, sentences, and logic; meaning, reference and thought; relativism and theories of truth; personal identity, the self and the brain; knowledge and belief; consciousness and the neural correlates of consciousness; dreaming and skepticism; materialism or physicalism, concepts and the mind-body problem; freewill and neurological determinism. Cumulative Skills: IND MW 10:30AM-11:50AM ASH 111 Additional Information: This philosophy course is oriented towards the Mind, Brain and, Information distribution area. CS-0111-1 DR Distribution Area: MBI The Emergence of Literacy Melissa Burch The majority of adults are able to read fluently. However, when children learn to read, the process is dependent on a number of skills and requires a great deal of adult guidance. In this course we will discuss the cultural importance of literacy across societies and throughout childhood. We will focus on the development of the complex skill of reading, including phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, and higher-order processes that contribute to decoding and text comprehension. Because instruction can play a determining factor in children's acquisition of literacy skills, we will study early reading materials and examine strategies that are employed in the classroom to facilitate the acquisition of these skills. Evaluation will be based on class participation, a series of short papers, and a longer final project. -

Custom, Law and John Company in Kumaon

Custom, law and John Company in Kumaon. The meeting of local custom with the emergent formal governmental practices of the British East India Company in the Himalayan region of Kumaon, 1815–1843. Mark Gordon Jones, November 2018. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. © Copyright by Mark G. Jones, 2018. All Rights Reserved. This thesis is an original work entirely written by the author. It has a word count of 89,374 with title, abstract, acknowledgements, footnotes, tables, glossary, bibliography and appendices excluded. Mark Jones The text of this thesis is set in Garamond 13 and uses the spelling system of the Oxford English Dictionary, January 2018 Update found at www.oed.com. Anglo-Indian and Kumaoni words not found in the OED or where the common spelling in Kumaon is at a great distance from that of the OED are italicized. To assist the reader, a glossary of many of these words including some found in the OED is provided following the main thesis text. References are set in Garamond 10 in a format compliant with the Chicago Manual of Style 16 notes and bibliography system found at http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org ii Acknowledgements Many people and institutions have contributed to the research and skills development embodied in this thesis. The first of these that I would like to acknowledge is the Chair of my supervisory panel Dr Meera Ashar who has provided warm, positive encouragement, calmed my panic attacks, occasionally called a spade a spade but, most importantly, constantly challenged me to chart my own way forward. -

Old Words, New Worlds: Revisiting the Modernity of Tradition

Old Words, New Worlds: Revisiting the Modernity of Tradition Ananya Vajpeyi n the Hindi film Raincoat (2004), review article we begin to look, Kalidasa and Krishna, Rituparno Ghosh presents a short story Vyasa and Valmiki are everywhere in the Iby O Henry in an Indian milieu. The The Modernity of Sanskrit by Simona Sawhney art and literature of modern India, as are place is contemporary middle class Kolkata; (Ranikhet: Permanent Black; co-published by University of many other authors, characters, tropes the main actors, drawn from Bollywood, Minnesota Press), 2009; pp 226, Rs 495 (HB). and narratives that invariably appear to us are at home in the present. Most of the as familiar, yet differently relevant in dif- conversation between various characters his updating and Indianising O Henry’s ferent contexts. They require no introduc- revolves around cell phones, TV channels, tale, but in his simultaneous reference to tion for any given audience, yet at each soap operas, air-conditioning and auto- post-colonial, colonial and pre-colonial new site where they turn up, as it were, mated teller machines, leaving us in no Bengali culture, and thus to a dense under- there is the interpretive space to figure out doubt as to the setting. But given that the belly of significance that gives weight to what exactly makes them pertinent on story is somewhat slow, and the acting by an otherwise trivial story. Calcutta’s status this occasion. Thus the work of writing the female lead, Aishwarya Rai indifferent as a big city, its urban decrepitude, its faded and reading is always ongoing, always at best, what gives the film its shadowed imperial grandeur and grinding poverty, inter-textual, always citational, and unfolds mood is its beautiful music, and the direc- these we already compute; so too the within a framework that blurs rather than tor’s obvious love for Kolkata. -

View/Download File

CURRICULUM VITAE FREDERICK MARCUS SMITH Department of Religious Studies Department of Asian & Slavic Languages & Literature 314 Gilmore Hall 111 Phillips Hall University of Iowa University of Iowa Iowa City, Iowa 52242 USA Iowa City, Iowa 52242 USA Tel. home: (319) 338-7193, office: (319) 335-2178 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL HISTORY Higher Education University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Ph.D. Oriental Studies, 1984. Poona University, Poona, India. M.A. Center for Advanced Study in Sanskrit, 1976. University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa. Graduate Studies in Chinese Language and Religion, 1970-72. Coe College, Cedar Rapids, Iowa. B.A., History, 1969. Academic Positions 2013 – Fall semester Stewart Fellow in the Princeton Humanities Council, Visiting Professor of South Asian Studies, Princeton University 2008 – present Professor of Sanskrit and Classical Indian Religions, University of Iowa. 1997 - 2008 Associate Professor of Sanskrit and Classical Indian Religions, University of Iowa. 1991 – 1997 Assistant Professor, University of Iowa. 1989 - 1991 Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Iowa. 2006 – Summer Visiting Associate Professor, University of New Mexico. 2000 - Fall semester Visiting Associate Professor, University of Pennsylvania. 1997 - present Associate Professor, University of Iowa. 1987 - 1989 Visiting Lecturer, Department of Oriental Studies, University of Pennsylvania. 1986 - 1987 Visiting Lecturer in Sanskrit, South Asia Regional Studies Department, University of Pennsylvania. 1983 - 1984 Research Assistant in Oriental Studies Department, University of Pennsylvania. 1982 - 1983 Teaching Fellow for Sanskrit, University of Pennsylvania. SCHOLARSHIP Refereed Publications Books 2006 The Self Possessed: Deity and Spirit Possession in South Asian Literature and Civilization. New York: Columbia University Press (pp. xxxiv + 701). -

2018-2019 University of Chicago 3

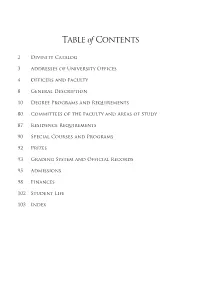

Table of Contents 2 Divinity Catalog 3 Addresses of University Offices 4 Officers and Faculty 8 General Description 10 Degree Programs and Requirements 80 Committees of the Faculty and Areas of Study 87 Residence Requirements 90 Special Courses and Programs 92 Prizes 93 Grading System and Official Records 95 Admissions 98 Finances 102 Student Life 103 Index 2 Divinity Catalog Divinity Catalog Announcements 2018-2019 Welcome to the University of Chicago Divinity School. More information regarding the University of Chicago Divinity School can be found online at http:// divinity.uchicago.edu. Or you may contact us at: Divinity School University of Chicago 1025 E. 58th St. Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone: 773-702-8200 Photograph by Alex S. MacLean. The information in these Announcements is correct as of August 1, 2018. It is subject to change. 2018-2019 University of Chicago 3 Addresses of University Offices Requests for information, materials, and application forms for admission and financial aid should be addressed as follows: For all matters pertaining to the Divinity School: Dean of Students The University of Chicago Divinity School 1025 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Phone: 773-702-8217 Fax: 773-834-4581 Web site: http://divinity.uchicago.edu For the Graduate Record Examination: Graduate Record Examination P.O. Box 6000 Princeton New Jersey 08541-6000 Phone: 609-771-7670 Web site: http://www.gre.org For FAFSA forms: Federal Student Aid Information Center P.O. Box 84 Washington, D.C. 20044 Phone: 800-433-3243 Web site: http://www.fafsa.gov For Housing: Residential Properties (RP) 773.753.2218 | [email protected] Web site: http://rp.uchicago.edu/ International House 1414 East 59th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Phone: 773-753-2280 Fax: 773-753-1227 Web site: http://ihouse.uchicago.edu For Student Loans: Graduate Aid Walker Museum 1115 E. -

On Hinduism by Wendy Doniger.Pdf

ON HINDUISM ON HINDUISM ~ Wendy Doniger Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Wendy Doniger 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Doniger, Wendy. [Essays. Selections] On Hinduism / Wendy Doniger. pages cm ISBN 978-0-19-936007-9 (hardback : alk. paper)