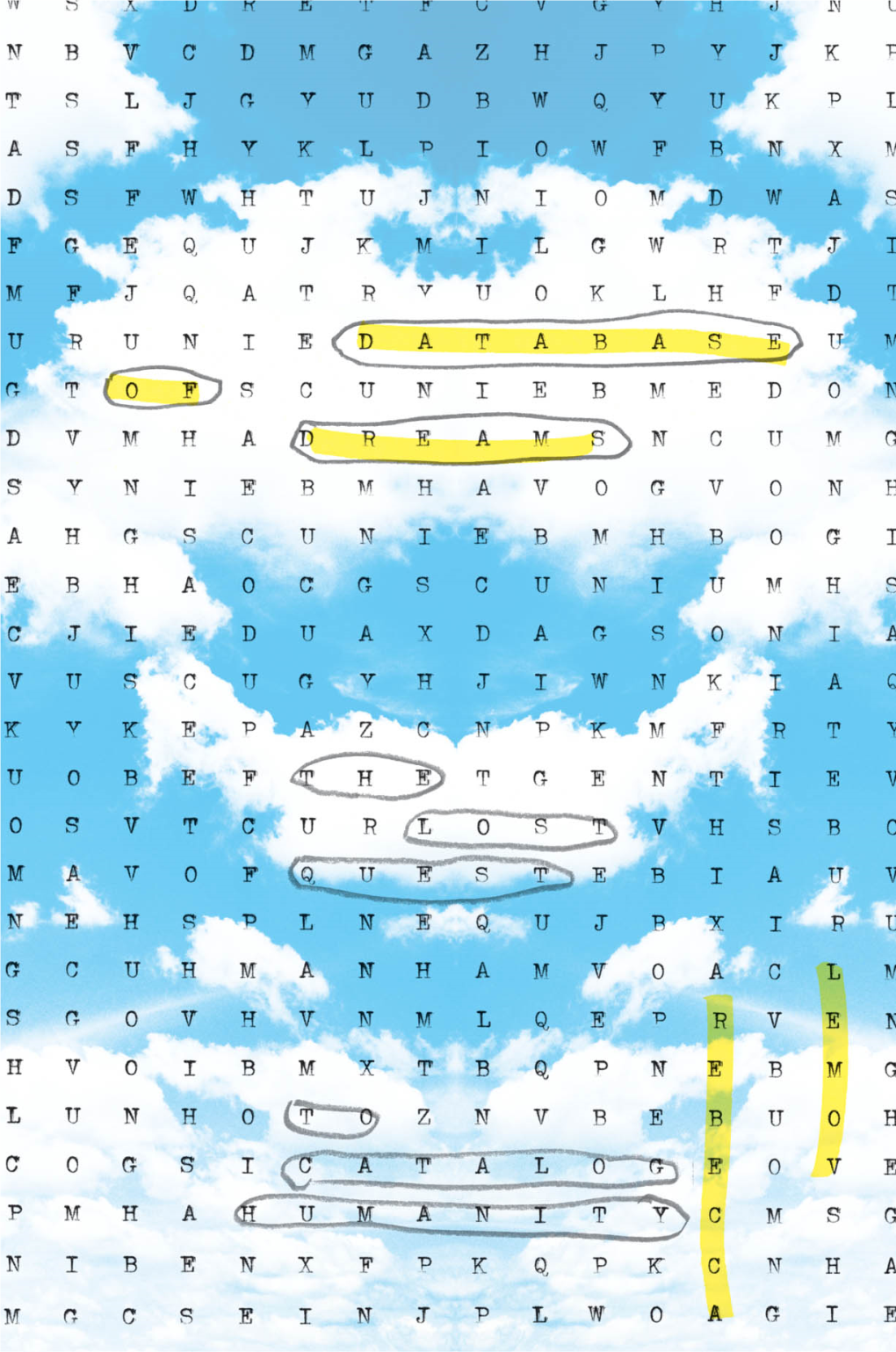

Database of Dreams This Page Intentionally Left Blank DATABASE of DREAMS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Introspectionism' and the Mythical Origins of Scientific Psychology

Consciousness and Cognition Consciousness and Cognition 15 (2006) 634–654 www.elsevier.com/locate/concog ‘Introspectionism’ and the mythical origins of scientific psychology Alan Costall Department of Psychology, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Hampshire PO1 2DY, UK Received 1 May 2006 Abstract According to the majority of the textbooks, the history of modern, scientific psychology can be tidily encapsulated in the following three stages. Scientific psychology began with a commitment to the study of mind, but based on the method of introspection. Watson rejected introspectionism as both unreliable and effete, and redefined psychology, instead, as the science of behaviour. The cognitive revolution, in turn, replaced the mind as the subject of study, and rejected both behaviourism and a reliance on introspection. This paper argues that all three stages of this history are largely mythical. Introspectionism was never a dominant movement within modern psychology, and the method of introspection never went away. Furthermore, this version of psychology’s history obscures some deep conceptual problems, not least surrounding the modern conception of ‘‘behaviour,’’ that continues to make the scientific study of consciousness seem so weird. Ó 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Introspection; Introspectionism; Behaviourism; Dualism; Watson; Wundt 1. Introduction Probably the most immediate result of the acceptance of the behaviorist’s view will be the elimination of self-observation and of the introspective reports resulting from such a method. (Watson, 1913b, p. 428). The problem of consciousness occupies an analogous position for cognitive psychology as the prob- lem of language behavior does for behaviorism, namely, an unsolved anomaly within the domain of an approach. -

The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought 1

The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought 1 The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought Department Website: http://socialthought.uchicago.edu Chair • Robert Pippin Professors • Lorraine Daston • Wendy Doniger • Joel Isaac • Hans Joas • Gabriel Lear • Jonathan Lear • Jonathan Levy • Jean Luc Marion • Heinrich Meier • Glenn W. Most • David Nirenberg • Thomas Pavel • Mark Payne • Robert B. Pippin • Jennifer Pitts • Andrei Pop • Haun Saussy • Laura Slatkin • Nathan Tarcov • Rosanna Warren • David Wellbery Emeriti • Wendy Doniger • Leon Kass • Joel Kraemer • Ralph Lerner • James M. Redfield • David Tracy About the Committee The John U. Nef Committee on Social Thought was established as a degree granting body in 1941 by the historian John U. Nef (1899-1988), with the assistance of the economist Frank Knight, the anthropologist Robert Redfield, and Robert M. Hutchins, then President of the University. The Committee is a group of diverse scholars sharing a common concern for the unity of the human sciences. Their premises were that the serious study of any academic topic, or of any philosophical or literary work, is best prepared for by a wide and deep acquaintance with the fundamental issues presupposed in all such studies, that students should learn about these issues by acquainting themselves with a select number of classic ancient and modern texts in an inter- disciplinary atmosphere, and should only then concentrate on a specific dissertation topic. It accepts qualified graduate students seeking to pursue their particular studies within this broader context, and aims both to teach precision of scholarship and to foster awareness of the permanent questions at the origin of all learned inquiry. -

Destroying Krishna Imagery. What Are the Limits of Academic and Artistic Freedom? Maruška Svašek

Destroying Krishna Imagery. What are the Limits of Academic and Artistic Freedom? Maruška Svašek [ f i g . 1 ] Pramod Pathak: Wendy’s Unhistory making History, screenshot A photograph published in by Organiser, a weekly magazine based in New Delhi, shows a group of Indian demonstrators holding up various placards. »Don’t insult Hindu Lords« is printed on one of them; »Stop Prejudice Hate Talk Discriminating against Hindus« and »Abuse is not intelligent discourse« are written on others. Another placard addresses the target of the demonstra- tion: »Wendy Doniger Please don’t insult our Hindu Lords.« (Fig. ). An Internet search for »Wendy Doniger« leads to the other side of the globe, to the prestigious University of Chicago Divinity School. The Uni- versity website states that Professor Doniger specializes in Hinduism and Maruška Svašek - 9783846763452 Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 01:19:58AM via free access [ f i g . 2 ] Wendy Doniger’s home page on the University of Chicago’s website, screenshot mythology, has published over forty books on related topics in these fields, and received her postgraduate degrees from Harvard University and the Uni- versity of Oxford. In Chicago, Doniger holds the position of Mircea Eliade Distinguished Service Professor of the History of Religions and is associated with the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations and to the Committee on Social Thought (Fig. ). Clearly, she is a highly successful, inter- nationally renowned scholar who is considered an expert in her field. So why the accusations of blasphemy and prejudice? What compelled a group of Hindus to gather and protest against her? Maruška Svašek - 9783846763452 Downloaded from Brill.com10/04/2021 01:19:58AM via free access In Organiser, this photograph was used to illustrate an article by Pramod Pathak, a Vedic scholar based in Goa, entitled »Wendy’s unhistory making history.« The piece was highly critical of Doniger’s latest book, The Hindus. -

The Ancient World 1.800.405.1619/Yalebooks.Com Now Available in Paperback Recent & Classic Titles

2017 The Ancient World 1.800.405.1619/yalebooks.com Now available in paperback Recent & Classic Titles & Pax Romana Augustus War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World First Emperor of Rome ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY Renowned scholar Adrian Goldsworthy Caesar Augustus’ story, one of the most turns to the Pax Romana, a rare period riveting in western history, is filled with when the Roman Empire was at peace. A drama and contradiction, risky gambles vivid exploration of nearly two centuries and unexpected success. This biography of Roman history, Pax Romana recounts captures the real man behind the crafted real stories of aggressive conquerors, image, his era, and his influence over two failed rebellions, and unlikely alliances. millennia. “An excellent book. First-rate.” Paper 2015 640 pp. 43 b/w illus. + 13 maps —Richard A. Gabriel, Military History 978-0-300-21666-0 $20.00 Paper 2016 528 pp. 36 b/w illus. Cloth 2014 624 pp. 43 b/w illus. + 13 maps 978-0-300-23062-8 $22.00 978-0-300-17872-2 $35.00 Hardcover 2016 528 pp. 36 b/w illus. 978-0-300-17882-1 $32.50 Caesar Life of a Colossus Recent & Classic Titles ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY This major new biography by a distin- guished British historian offers a remark- In the Name of Rome ably comprehensive portrait of a leader The Men Who Won the Roman Empire whose actions changed the course of ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY; WITH A NEW PREFACE Western history and resonate some two A world-renowned authority offers a thousand years later. -

Early Childhood Memory and Attention As Predictors of Academic Growth Trajectories

Running head: MEMORY, ATTENTION AND ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT 1 Early Childhood Memory and Attention as Predictors of Academic Growth Trajectories Deborah Stipek and Rachel Valentino Stanford University Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Deborah Stipek, Graduate School of Education, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305. Email: [email protected] Running head: MEMORY, ATTENTION AND ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT 2 Abstract Longitudinal data from the children of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) were used to assess how well measures of short-term and working memory and attention in early childhood predicted longitudinal growth trajectories in mathematics and reading comprehension. Analyses also examined whether changes in memory and attention were more strongly predictive of changes in academic skills in early childhood than in later childhood. All predictors were significantly associated with academic achievement and years of schooling attained, although the latter was at least partially mediated by predictors’ effect on academic achievement in adolescence. The relationship of working memory and attention with academic outcomes was also found to be strong and positive in early childhood, but non-significant or small and negative in later years. The study results provide support for a “fade-out” hypothesis, which suggests that underlying cognitive capacities predict learning in the early elementary grades, but the relationship fades by late elementary school. These findings suggest that whereas efforts to develop attention and memory may improve academic achievement in the early grades, in the later grades interventions that focus directly on subject matter learning are more likely to improve achievement. Running head: MEMORY, ATTENTION AND ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT 3 Early Childhood Memory and Attention as Predictors of Academic Growth Trajectories Success in school requires many skills. -

Women Psychologists and Gender Politics During World War II

Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 42. No. I, 1986, pp. 157-180 “We would not take no for an answer”: Women Psychologists and Gender Politics During World War I1 James H. Capshew and Alejandra C. Laszlo University of Pennsylvania This essay explores the complex relationship among gender, professionalization, and ideology that developed as psychologists mobilized for World War It. Upon being excluded from mobilization plans by the male leaders of the profession, women psychologists organized the National Council of Women Psychologists to advance their interests. But while their male colleagues enjoyed new employment opportunities in the military services and government agencies, the women were confined largely to volunteer activities in their local communities. Although women psychologists succeeded in gaining representation on wartime commit- tees and in drawing attention to their professional problems, they were unable to change the status quo in psychology. Situated in a cultural milieu ihat stressed the masculine nature of science, women psychologists were hampered by their own acceptance of a professional ideology of meritocratic reward, and remained ambivalent about their feminist activities. Throughout the 20th century women have increasingly challenged the as- sumption that they are neither interested in nor qualified for scientific careers. It is also true that as women successfully breached this overwhelmingly male bastion, a growing body of biological, social, and cultural arguments were advanced to rationalize their usually restricted scientific role. This was especially evident during the Second World War, as social and economic forces strained existing professional relationships. Permission to quote from unpublished materials has been granted by Alice I. Bryan, Carnegie- Mellon University Libraries, Harvard University Archives, Stanford University Archives, and Yale University Library. -

Testing the Elite: Yale College in the Revolutionary Era, 1740-1815

St. John's University St. John's Scholar Theses and Dissertations 2021 TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740-1815 David Andrew Wilock Saint John's University, Jamaica New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations Recommended Citation Wilock, David Andrew, "TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740-1815" (2021). Theses and Dissertations. 255. https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations/255 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by St. John's Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of St. John's Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740- 1815 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY to the faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY of ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES at ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY New York by David A. Wilock Date Submitted ____________ Date Approved________ ____________ ________________ David Wilock Timothy Milford, Ph.D. © Copyright by David A. Wilock 2021 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740- 1815 David A. Wilock It is the goal of this dissertation to investigate the institution of Yale College and those who called it home during the Revolutionary Period in America. In so doing, it is hoped that this study will inform a much larger debate about the very nature of the American Revolution itself. The role of various rectors and presidents will be considered, as well as those who worked for the institution and those who studied there. -

Towards the Implementation of an Intelligent Software Agent for the Elderly Amir Hossein Faghih Dinevari

Towards the Implementation of an Intelligent Software Agent for the Elderly by Amir Hossein Faghih Dinevari A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Computing Science University of Alberta c Amir Hossein Faghih Dinevari, 2017 Abstract With the growing population of the elderly and the decline of population growth rate, developed countries are facing problems in taking care of their elderly. One of the issues that is becoming more severe is the issue of compan- ionship for the aged people, particularly those who chose to live independently. In order to assist the elderly, we suggest the idea of a software conversational intelligent agent as a companion and assistant. In this work, we look into the different components that are necessary for creating a personal conversational agent. We have a preliminary implementa- tion of each component. Among them, we have a personalized knowledge base which is populated by the extracted information from the conversations be- tween the user and the agent. We believe that having a personalized knowledge base helps the agent in having better, more fluent and contextual conversa- tions. We created a prototype system and conducted a preliminary evaluation to assess by users conversations of an agent with and without a personalized knowledge base. ii Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Motivation . 1 1.1.1 Population Trends . 1 1.1.2 Living Options for the Elderly . 2 1.1.3 Companionship . 3 1.1.4 Current Technologies . 4 1.2 Proposed System . 5 1.2.1 Personal Assistant Functionalities . -

Emotionally Charged Autobiographical Memories Across the Life Span: the Recall of Happy, Sad, Traumatic, and Involuntary Memories

Psychology and Aging Copyright 2002 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2002, Vol. 17, No. 4, 636–652 0882-7974/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.636 Emotionally Charged Autobiographical Memories Across the Life Span: The Recall of Happy, Sad, Traumatic, and Involuntary Memories Dorthe Berntsen David C. Rubin University of Aarhus Duke University A sample of 1,241 respondents between 20 and 93 years old were asked their age in their happiest, saddest, most traumatic, most important memory, and most recent involuntary memory. For older respondents, there was a clear bump in the 20s for the most important and happiest memories. In contrast, saddest and most traumatic memories showed a monotonically decreasing retention function. Happy involuntary memories were over twice as common as unhappy ones, and only happy involuntary memories showed a bump in the 20s. Life scripts favoring positive events in young adulthood can account for the findings. Standard accounts of the bump need to be modified, for example, by repression or reduced rehearsal of negative events due to life change or social censure. Many studies have examined the distribution of autobiographi- (1885/1964) drew attention to conscious memories that arise un- cal memories across the life span. No studies have examined intendedly and treated them as one of three distinct classes of whether this distribution is different for different classes of emo- memory, but did not study them himself. In his well-known tional memories. Here, we compare the event ages of people’s textbook, Miller (1962/1974) opened his chapter on memory by most important, happiest, saddest, and most traumatic memories quoting Marcel Proust’s description of how the taste of a Made- and most recent involuntary memory to explore whether different leine cookie unintendedly brought to his mind a long-forgotten kinds of emotional memories follow similar patterns of retention. -

Culture Effects on Adults' Earliest Childhood Recollection and Self-Description: Implications for the Relation Between Memory and the Self

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Copyright 2001 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2001, Vol. 81, No. 2, 220-233 0022-3514/01/S5.00 DOI: 10.1037//OO22-3514.81.2.220 Culture Effects on Adults' Earliest Childhood Recollection and Self-Description: Implications for the Relation Between Memory and the Self Qi Wang Cornell University American and Chinese college students (N = 256) reported their earliest childhood memory on a memory questionnaire and provided self-descriptions on a shortened 20 Statements Test (M. H. Kuhn & T. S. McPartland, 1954). The average age at earliest memory of Americans was almost 6 months earlier than that of Chinese. Americans reported lengthy, specific, self-focused, and emotionally elaborate memories; they also placed emphasis on individual attributes in describing themselves. Chinese provided brief accounts of childhood memories centering on collective activities, general routines, and emotionally neutral events; they also included a great number of social roles in their self-descriptions. Across the entire sample, individuals who described themselves in more self-focused and positive terms provided more specific and self-focused memories. Findings are discussed in light of the interactive relation between autobiographical memory and cultural self-construal. When asked to think of her earliest childhood memory, a Har- The work of early theorists (e.g., Greenwald, 1980; Kelly, 1955; vard undergraduate wrote down the following episode that hap- Markus, 1977; Rogers, Kuiper, & Kirker, 1977; Schachtel, 1947) pened when she was about 3 years old: foreshadowed the interface between the self and autobiographical memory. For example, George Kelly (1955) proposed that a per- I remember standing in my aunt's spacious blue bedroom and looking sonal experience must be supported within an existing self- up at the ceiling. -

Between the Margin and the Text

BETWEEN THE MARGIN AND THE TEXT He kanohi kē to Te Pākehā-Māori Huhana Forsyth A thesis submitted to AUT University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2013 Faculty of Te Ara Poutama i Table of Contents Attestation.............................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements............................................................................... vii Abstract.................................................................................................. viii Preface.................................................................................................... ix Chapter One: Background to the study.............................................. 1 i. Researcher’s personal story......................................................... 2 ii. Emergence of the topic for the study............................................ 3 iii. Impetus for the study.................................................................... 8 iv. Overall approach to the study....................................................... 9 Chapter Two: The Whakapapa of Pākehā-Māori……………………… 11 i. Pre-contact Māori society and identity......................................... 11 ii. Whakapapa of the term Pākehā-Māori……………………………. 13 iii. Socio-historical context................................................................. 18 iv. Pākehā-Māori in the socio-historical context................................ 22 v. Current socio-cultural context...................................................... -

Douglas Mcglashan Kelley Papers, Date (Inclusive): Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5d5nc7tj No online items Guide to the Douglas McGlashan Kelley Papers Processed by UCSC OAC Unit. The University Library Special Collections and Archives University Library University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, California, 95064 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucsc.edu/speccoll/ © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Social Sciences--Sociology--Crime Guide to the Douglas McGlashan MS 229 1 Kelley Papers Guide to the Douglas McGlashan Kelley Papers Collection number: MS 229 The University Library Special Collections and Archives University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, California Contact Information: Special Collections and Archives University Library University of California, Santa Cruz Santa Cruz, California, 95064 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.ucsc.edu/speccoll/ Processed by: UCSC OAC Unit Date Completed: August 2004 Encoded by: UCSC OAC Unit © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Douglas McGlashan Kelley papers, Date (inclusive): ca. 1939-1959 Collection number: MS 229 Creator: Kelley, Douglas McGlashan Extent: 7 boxes 4 linear ft. Repository: University of California, Santa Cruz. University Library. Special Collections and Archives Santa Cruz, California 95064 Abstract: This collection consists of correspondence, television scripts and publications related to the criminological and pedagogical work of psychiatrist Douglas McGlashan Kelley. Physical location: Stored in Special Collections & Archives: Advance notice is required for access to the papers. Language: English. Access Collection is available for research. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the University of California. Literary rights are retained by the creators of the records and their heirs.