Autobiographies: Psychoanalysis and the Graphic Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discursive Construction of Referential Truth in Art Spiegelman's Maus And

The Comic Book as Complex Narrative: Discursive Construction of Referential Truth in Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis By Hannah Beckler For honors in The Department of Humanities Examination Committee: Annjeanette Wiese Thesis Advisor, Humanities Paul Gordon Honors Council Representative, Humanitities Paul Levitt Committee Member, English April 2014 University of Colorado at Boulder Beckler 2 Abstract This paper addresses the discursive construction of referential truth in Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. I argue that referential truth is obtained through the inclusion of both correlative truth and metafictional self-reflection within a nonfictional work. Rather than detracting from their obtainment of referential truth, the comic book discourses of both Maus and Persepolis actually increase the degree of both referential truth and subsequent perceived nonfictionality. This paper examines the cognitive processes employed by graphic memoirs to increase correlative truth as well as the discursive elements that facilitate greater metafictional self-awareness in the work itself. Through such an analysis, I assert that the comic discourses of Maus and Persepolis increase the referential truth of both works as well as their subsequent perceived nonfictionality. Beckler 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………….4 2. Part One: Character Recognition and Reader Identification in Images……..7 3. Part Two: Representing Space, Time, and Movement……………………..15 4. Part Three: Words and Images……………………………………………..29 5. Part Four: The Problem of Memory in Representation……………...……..34 6. Part Five: Subjective Reconstruction and Narration……………………….48 7. Conclusion………………………………………………………………….56 Works Cited………………………………………………………………...60 Beckler 4 Although comic books are often considered a lower medium of literary and artistic expression compared to works of literature, art, or film, modern graphic novels often challenge the assumption that such a medium is not capable of communicating complex and nuanced stories. -

The Ancient World 1.800.405.1619/Yalebooks.Com Now Available in Paperback Recent & Classic Titles

2017 The Ancient World 1.800.405.1619/yalebooks.com Now available in paperback Recent & Classic Titles & Pax Romana Augustus War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World First Emperor of Rome ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY Renowned scholar Adrian Goldsworthy Caesar Augustus’ story, one of the most turns to the Pax Romana, a rare period riveting in western history, is filled with when the Roman Empire was at peace. A drama and contradiction, risky gambles vivid exploration of nearly two centuries and unexpected success. This biography of Roman history, Pax Romana recounts captures the real man behind the crafted real stories of aggressive conquerors, image, his era, and his influence over two failed rebellions, and unlikely alliances. millennia. “An excellent book. First-rate.” Paper 2015 640 pp. 43 b/w illus. + 13 maps —Richard A. Gabriel, Military History 978-0-300-21666-0 $20.00 Paper 2016 528 pp. 36 b/w illus. Cloth 2014 624 pp. 43 b/w illus. + 13 maps 978-0-300-23062-8 $22.00 978-0-300-17872-2 $35.00 Hardcover 2016 528 pp. 36 b/w illus. 978-0-300-17882-1 $32.50 Caesar Life of a Colossus Recent & Classic Titles ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY This major new biography by a distin- guished British historian offers a remark- In the Name of Rome ably comprehensive portrait of a leader The Men Who Won the Roman Empire whose actions changed the course of ADRIAN GOLDSWORTHY; WITH A NEW PREFACE Western history and resonate some two A world-renowned authority offers a thousand years later. -

Testing the Elite: Yale College in the Revolutionary Era, 1740-1815

St. John's University St. John's Scholar Theses and Dissertations 2021 TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740-1815 David Andrew Wilock Saint John's University, Jamaica New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations Recommended Citation Wilock, David Andrew, "TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740-1815" (2021). Theses and Dissertations. 255. https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations/255 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by St. John's Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of St. John's Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740- 1815 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY to the faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY of ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES at ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY New York by David A. Wilock Date Submitted ____________ Date Approved________ ____________ ________________ David Wilock Timothy Milford, Ph.D. © Copyright by David A. Wilock 2021 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740- 1815 David A. Wilock It is the goal of this dissertation to investigate the institution of Yale College and those who called it home during the Revolutionary Period in America. In so doing, it is hoped that this study will inform a much larger debate about the very nature of the American Revolution itself. The role of various rectors and presidents will be considered, as well as those who worked for the institution and those who studied there. -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

Check All That Apply)

Form Version: February 2001 EFFECTIVE TERM: Fall 2003 PALOMAR COLLEGE COURSE OUTLINE OF RECORD FOR DEGREE CREDIT COURSE X Transfer Course X A.A. Degree applicable course (check all that apply) COURSE NUMBER AND TITLE: ENG 290 -- Comic Books As Literature UNIT VALUE: 3 MINIMUM NUMBER OF SEMESTER HOURS: 48 BASIC SKILLS REQUIREMENTS: Appropriate Language Skills ENTRANCE REQUIREMENTS PREREQUISITE: Eligibility for ENG 100 COREQUISITE: NONE RECOMMENDED PREPARATION: NONE SCOPE OF COURSE: An analysis of the comic book in terms of its unique poetics (the complicated interplay of word and image); the themes that are suggested in various works; the history and development of the form and its subgenres; and the expectations of comic book readers. Examines the influence of history, culture, and economics on comic book artists and writers. Explores definitions of “literature,” how these definitions apply to comic books, and the tensions that arise from such applications. SPECIFIC COURSE OBJECTIVES: The successful student will: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the unique poetics of comic books and how that poetics differs from other media, such as prose and film. 2. Analyze representative works in order to interpret their styles, themes, and audience expectations, and compare and contrast the styles, themes, and audience expectations of works by several different artists/writers. 3. Demonstrate knowledge about the history and development of the comic book as an artistic, narrative form. 4. Demonstrate knowledge about the characteristics of and developments in the various subgenres of comic books (e.g., war comics, horror comics, superhero comics, underground comics). 5. Identify important historical, cultural, and economic factors that have influenced comic book artists/writers. -

Download at Yalebooks.Com

World 2014 Languages Yale university press Connect with Yale World Languages yalebooks.com/languages Request free examination copies at yalebooks.com/languageexam. View many titles online at yalebooks.com/e-exam. Excerpts from many of our titles are available on our website on each book’s page. Author Index Contact Us Abbona-Sneider, Chouairi, 18 Huffman & Proum, 38 Orr-Stav, 34 Borra, & Pausini, 12 Chyet, 37 Hussein, 19 Patrikis, 40 Tim Shea Abed, 19 Claxton, 24 Johnson, 39, 40 Perini, 10 Agosin, 9 Colligan-Taylor, 27 Jorden & Piñar, 8 Editor, Languages Alhawary, 18 Coria-Sánchez & Chaplin, 27 Pinto & de Pablo- [email protected] Alosh, 20 Torres, 8, 9 Jorden & Noda, 27 Ortega, 7 Antes, 13 Cortez de Katz & Blyth, 13 Pfrehm, 22 Asani & Hyder, 37 Andersen, 7 Keller & Russell, Rifkin et al., 35 Ash Lago Baccouche & Cotton, Tolman & 24, 25 Rosengrant, 36 Azmi, 19 Mack, 6 Kittel et al., 34 Ross, 32 Publishing Assistant, Bai, 32 Davidson & Kumaravadivelu, 40 Ryan-Scheutz & Languages Bailey, 39 Lynch, 39 Link, 21 Marini-Maio, 12 Barnett, 16 DeFrancis, 33 López-Burton & Sánchez-Blake & [email protected] Bartalesi-Graf, 11 Dolidon & López- Minor, 39 Stycos, 9 Ben Zvi et al., 34 Burton, 16 Lubensky, 36 Savignon, 40 Berberi et al., 39 Donahue, 23 Lucas, 11 Schenker, 38 Karen Stickler Berg, 17 Doran, 17 Mahota, 36 Slade, 10 Academic Discipline Beyer, 26 Dostoevsky, 35 Melis, 11 Stilo et al., 37 Bilbao-Henry, 9 Dykstra-Pruim & Mickel, 33 Susskind, 14 Marketer Björkstén, 32 Redmann, 21 Mistacco, 14 Tang & Chen, 33 [email protected] Bjørnstad & Ibbett, 17 Echeruo, 37 Morgan, 7 Titus, 35 Bogomolov & Fedi & Fasoli, 11 Morris et al., 14 Wang, F. -

Kate Warren, “Persepolis: Animation, Representation and the Power of the Personal Story,” Screen Education, Winter 2010, Issue 58, PP

Kate Warren, “Persepolis: Animation, Representation and the Power of the Personal Story,” Screen Education, Winter 2010, Issue 58, PP. 117-23. Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis {2007), based on her graphic novels of the same name, is one of a growing number of films thiat employs formats such as animation, which is traditionally aimed at younger audiences, to depict complex and confronting subject matter. In doing so, such films offer interesting avenues of investigation for students and educators, not only in terms of the stories told, but also in relation to how these artistic and aesthetic techniques affect the narrative structures and modes of representation offered. Author, illustrator and filmmaker Marjane Satrapi was born in Rasht, Iran, in 1969.' As a child she witnessed one of the most dramatic periods in her country's recent history: the overthrow of the shah in 1979, the subsequent Islamic Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War. The film Persepolis charts her childhood in Tehran, her secondary education in Vienna and her tertiary studies in Iran, and concludes with her decision to leave Iran permanently for France. The formative years of childhood, adolescence and early adulthood are negotiated during a period of great flux and trauma for her country, her family and herself. Through her graphic novels and this film, Satrapi depicts these events and experiences with frankness, humour, poignancy and emotional power. Questions of representation When approaching cultural and historical traumas - such as war, revolution and genocide - questions are often raised about how these events are to be represented, who is 'entitled' to represent them, and whether they should be represented at all. -

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975044 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $12.99/$14.99 Can. cofounders Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley, Archie 112 pages expects this title to be a breakout success. Paperback / softback / Trade paperback (US) Comics & Graphic Novels / Fantasy From the the company that’s sold over 1 billion comic books Ctn Qty: 0 and the band that’s sold over 100 million albums and DVDs 0.8lb Wt comes this monumental crossover hit! Immortal rock icons 363g Wt KISS join forces ... Author Bio: Alex Segura is a comic book writer, novelist and musician. Alex has worked in comics for over a decade. Before coming to Archie, Alex served as Publicity Manager at DC Comics. Alex has also worked at Wizard Magazine, The Miami Herald, Newsarama.com and various other outlets and websites. Author Residence: New York, NY Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS: Collector's Edition Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent, Gene Simmons fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975143 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $29.99/$34.00 Can. -

Graphic Narrative in Contemporary Literature & Art: Evolution of Comic Book to Graphic Novel

An Elective Course for Undergraduate and Graduate Students of any discipline and for English Language Students GRAPHIC NARRATIVE IN CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE & ART: EVOLUTION OF COMIC BOOK TO GRAPHIC NOVEL ✓ Basic Requirements: Appropriate language skills required by the University. ➢ This course should be of interest to anyone concerned with verbal & visual communications, popular forms, mass culture, history and its representation, colonialism, politics, journalism, writing, philosophy, religion, mythology, mysticism, metaphysics, cultural exchanges, aesthetics, post-modernism, theatre, film, comic art, collections, popular art & culture, literature, fine arts, etc. ➢ This course may have a specific appeal to fans and/or to those who are curious about this vastly influential, widely popular, most complex and thought-provoking work of contemporary literature and art form, the ‘Comics’; however it does not presume a prior familiarity with graphic novels and/or comics, just an overall enthusiasm to learn new things from a new angle and an open mind. ✓ Prerequisites: ➢ FA489: ‘By consent’ selection of students. ➢ FA490: Upon successful completion of FA489. ✓ Co-requisites: ➢ FA489: Freshmen who graduated from a high school with an English curriculum or passed BU proficiency test with an A; & sophomore, junior, senior students. ➢ FA490: Successful completion of FA 489. ✓ No requisites: FA49V. ✓ Recommended Preparation: Reading all of the required readings and as many from the suggested reading list. Idea Description: Is ‘comics’ a form of both literature and art? Certainly the answer is “yes” but there are many people who reject the idea, yet many other people call those people old-school intellectuals. However, in recent years, many scholars, critics and faculty alike have accepted ‘comics’, often dubbed by many publishers as ‘graphic novel’, as a respected form of both literature and art. -

Spie a Fumetti Tra Vecchio E Nuovo Millennio

FUMETTO Spie a fumetti tra vecchio e nuovo millennio GIUSEPPE POLLICELLI A sinistra, primo numero della miniserie The Men in Black (1990); locandina del film Men in Black , diretto nel 1997 da Barry Sonnenfeld. Sotto, edizione italiana di Insiders pubblicato nel 2018 da Editoriale Aurea. bbiamo già incontrato gli Uomini in Nero – immaginari agenti del governo ame - Negli Stati Uniti d’America, dagli anni Novanta, ricano con il compito di occultare con qualsiasi mezzo, compreso l’omicidio, tutti si accresce notevolmente il numero delle case editrici i casi di avvistamenti alieni o di contatti con extraterrestri da parte di esseri indipendenti (alternative alle major DC Comics A umani – sul secondo numero del 2016 di « GNOSIS », occupandoci di Martin Mystère , il De - e Marvel) e questo fa sì che aumenti l’offerta di fumetti nel suo complesso. tective dell’Impossibile edito dalla Bonelli. Ebbene, nel 1990 lo sceneggiatore statunitense Ad ampliarsi sarà anche la quantità di opere Lowell Cunningham e il disegnatore canadese Sandy Carruthers hanno pubblicato per di genere spionistico, la più nota delle quali l’etichetta Aircel Comics di Ottawa (in seguito rilevata dalla Malibu Comics, a sua volta è The Men in Black , miniserie creata nel 1990 assorbita dalla Marvel) i tre numeri della miniserie The Men in Black , alla quale seguirà da Lowell Cunningham e Sandy Carruthers l’anno successivo una seconda, sempre di tre numeri, ottenendo un successo tanto inat - per una piccola etichetta canadese poi rilevata teso quanto vasto. Successo destinato a divenire planetario quando, nel 1997, il regista dalla Marvel. Da questa saga saranno tratti Barry Sonnenfeld ha tratto dal fumetto un film che si rivelerà campione d’incassi ai bot - tre film, interpretati dalla coppia Tommy Lee Jones teghini di tutto il mondo. -

Yale's Library from 1843 to 1931 Elizabeth D

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale MSSA Kaplan Prize for Yale History Library Prizes 5-2015 The rT ue University: Yale's Library from 1843 to 1931 Elizabeth D. James Yale University Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/mssa_yale_history Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation James, Elizabeth D., "The rT ue University: Yale's Library from 1843 to 1931" (2015). MSSA Kaplan Prize for Yale History. 5. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/mssa_yale_history/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Prizes at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in MSSA Kaplan Prize for Yale History by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The True University: Yale’s Library from 1843 to 1931 “The true university of these days is a collection of books.” -Thomas Carlyle, On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History Elizabeth James Branford College Professor Jay Gitlin April 6, 2015 2 Introduction By the summer of 1930, Sterling Memorial Library was nearing completion, lacking only the university’s 1.6 million books. At 6:00 AM on July 7, with a ceremonial parade of the library’s earliest accessions, the two-month project of moving the books commenced. Leading the trail of librarians was the head librarian, Andrew Keogh, and the head of the serials cataloguing department, Grace Pierpont Fuller. Fuller was the descendant of James Pierpont, one of the principal founders of Yale, and was carrying the Latin Bible given by her ancestor during the fabled 1701 donation of books that signaled the foundation of the Collegiate School. -

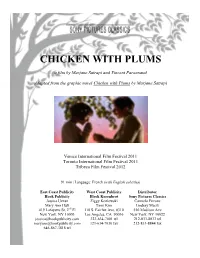

Chicken with Plums

CHICKEN WITH PLUMS a film by Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud Adapted from the graphic novel Chicken with Plums by Marjane Satrapi Venice International Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 Tribeca Film Festival 2012 91 min | Language: French (with English subtitles) East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Tami Kim Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS Teheran, 1958. Since his beloved violin was broken, Nasser Ali Khan, one of the most renowned musicians of his day, has lost all taste for life. Finding no instrument worthy of replacing it, he decides to confine himself to bed to await death. As he hopes for its arrival, he plunges into deep reveries, with dreams as melancholic as they are joyous, taking him back to his youth and even to a conversation with Azraël, the Angel of Death, who reveals the future of his children... As pieces of the puzzle gradually fit together, the poignant secret of his life comes to light: a wonderful story of love which inspired his genius and his music... DIRECTORS’ STATEMENT By Marjane Satrapi & Vincent Paronnaud Chicken with Plums is the story of a famous musician whose prized instrument has been ruined.