School Renaming Recommendations NO ACTION REQUIRED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sex and Shock Jocks: an Analysis of the Howard Stern and Bob & Tom Shows Lawrence Soley Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Communication, College of Publications 11-1-2007 Sex and Shock Jocks: An Analysis of the Howard Stern and Bob & Tom Shows Lawrence Soley Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. Journal of Promotion Management, Vol. 13, No. 1/2 (November 2007): 73-91. DOI. © 2007 Taylor & Francis (Routledge). Used with permission. NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page. Sex and Shock Jocks: An Analysis of the Howard Stern and Bob & Tom Shows Lawrence Soley Diederich College of Communication, Marquette University Milwaukee, WI Abstract: Studies of mass media show that sexual content has increased during the past three decades and is now commonplace. Research studies have examined the sexual content of many media, but not talk radio. A subcategory of talk radio, called “shock jock” radio, has been repeatedly accused of being indecent and sexually explicit. This study fills in this gap in the literature by presenting a short history and an exploratory content analysis of shock jock radio. The content analysis compares the sexual discussions of two radio talk shows: Infinity’s Howard Stern Show and Clear Channel’s Bob & Tom Show. Introduction The quantity and explicitness of sexual content in mass media has steadily increased during the past three decades. Greenberg and Busselle (1996) found that sexual activities depicted in soap operas increased between 1985 and 1994, rising from 3.67 actions per hour in 1985 to 6.64 per hour in 1994. -

A Descriptive Study of How African Americans Are Portrayed in Award Winning African American Children's Picture Books from 1996-2005

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2006 A Descriptive Study of How African Americans are Portrayed in Award Winning African American Children's Picture Books From 1996-2005 Susie Robin Ussery Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Ussery, Susie Robin, "A Descriptive Study of How African Americans are Portrayed in Award Winning African American Children's Picture Books From 1996-2005" (2006). Theses and Dissertations. 106. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/106 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF HOW AFRICAN AMERICANS ARE PORTRAYED IN AWARD WINNING AFRICAN AMERICAN CHILDREN’S PICTURE BOOKS FROM 1996-2005 By Susie Robin Ussery A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Elementary Education in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction Mississippi State, Mississippi May 2006 Copyright by Susie Robin Ussery 2006 Name: Susie Robin Ussery Date of Degree: May 13, 2006 Institution: Mississippi State University Major Field: Elementary Education Dissertation Director: Dr. Linda T. Coats Title of Study: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF HOW AFRICAN AMERICANS ARE PORTRAYED IN AWARD WINNING AFRICAN AMERICAN CHILDREN’S PICTURE BOOKS FROM 1996-2005 Pages in Study: 109 Candidate for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Children learn about their world through books used in the classroom. -

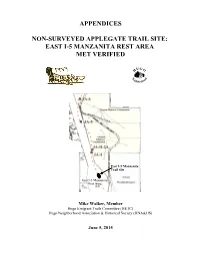

Appendices Non-Surveyed Applegate Trail Site: East I

APPENDICES NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED Mike Walker, Member Hugo Emigrant Trails Committee (HETC) Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HNA&HS) June 5, 2015 NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED APPENDICES Appendix A. Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HuNAHS) Standards for All Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix B. HuNAHS’ Policy for Document Verification & Reliability of Evidence Appendix C. HETC’s Standards: Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix D1. Pedestrian Survey of Stockpile Site South of Chancellor Quarry in the I-5 Jumpoff Joe-Glendale Project, Josephine County (separate web page) Appendix D2. Subsurface Reconnaissance of the I-5 Chancellor Quarry Stockpile Project, and Metal Detector Survey Within the George and Mary Harris 1854 - 55 DLC (separate web page) Appendix D3. May 18, 2011 Email/Letter to James Black, Planner, Josephine County Planning Department (separate web page) Appendix D4. The Rogue Indian War and the Harris Homestead Appendix D5. Future Studies Appendix E. General Principles Governing Trail Location & Verification Appendix F. Cardinal Rules of Trail Verification Appendix G. Ranking the Reliability of Evidence Used to Verify Trial Location Appendix H. Emigrant Trail Classification Categories Appendix I. GLO Surveyors Lake & Hyde Appendix J. Preservation Training: Official OCTA Training Briefings Appendix K. Using General Land Office Notes And Maps To Relocate Trail Related Features Appendix L1. Oregon Donation Land Act Appendix L2. Donation Land Claim Act Appendix M1. Oregon Land Survey, 1851-1855 Appendix M2. How Accurate Were the GLO Surveys? Appendix M3. Summary of Objects and Data Required to Be Noted In A GLO Survey Appendix M4. -

I-5 Scar of Displacement Revisited

Black History Month PO QR code ‘City of www.portlandobserver.com Volume XLVV • Number 4 Roses’ Wednesday • February 24, 2021 Committed to Cultural Diversity I-5 Scar of Displacement Revisited ODOT takes another look at Rose Quarter project BY BEVERLY CORBELL A swath Portland centered at Broadway and Weidler is cleared for construction of the I-5 freeway in this 1962 THE PORTLAND OBSERVER photo from the Eliot Neighborhood Association. Even many of the homes still standing were later lost to In June of last year, the nonprofit Albina Vision Trust demolition as the historic African American neighborhood was decimated over the 1960s and early 1970s, not sent an email to the Oregon Department of Transportation only for I-5, but to make room for the Memorial Coliseum, its parking lots, the Portland Public School’s Blanchard withdrawing support for its proposed I-5 Rose Quarter Im- Building, I-405 ramps, and Emanuel Hospital’s expansion. provement Project, which would reconfigure a 1.8-mile stretch of I-5 between the Interstate 84 and Interstate 405 the grassroots effort that began in 2017 to remake the Rose interchanges. Quarter district into a fully functioning neighborhood, em- According to Winta Yohannes, Albina Vision’s manag- bracing its diverse past and re-creating a landscape that can ing director, the proposal didn’t go far enough to mitigate accommodate much more than its two sports and entertain- the harm done to the Black community in the Albina neigh- ment venues, but with several officials, including Mayor borhood when hundreds, maybe thousands, of homes and Ted Wheeler, also dropping support for the project. -

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Paul Harold Rubinson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War Committee: —————————————————— Mark A. Lawrence, Supervisor —————————————————— Francis J. Gavin —————————————————— Bruce J. Hunt —————————————————— David M. Oshinsky —————————————————— Michael B. Stoff Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War by Paul Harold Rubinson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Acknowledgements Thanks first and foremost to Mark Lawrence for his guidance, support, and enthusiasm throughout this project. It would be impossible to overstate how essential his insight and mentoring have been to this dissertation and my career in general. Just as important has been his camaraderie, which made the researching and writing of this dissertation infinitely more rewarding. Thanks as well to Bruce Hunt for his support. Especially helpful was his incisive feedback, which both encouraged me to think through my ideas more thoroughly, and reined me in when my writing overshot my argument. I offer my sincerest gratitude to the Smith Richardson Foundation and Yale University International Security Studies for the Predoctoral Fellowship that allowed me to do the bulk of the writing of this dissertation. Thanks also to the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale University, and John Gaddis and the incomparable Ann Carter-Drier at ISS. -

BLACK HISTORY – PERTH AMBOY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Black History in Kindergarten

BLACK HISTORY – PERTH AMBOY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Black History in Kindergarten Read and Discuss and Act out: The Life's Contributions of: Ruby Bridges Bill Cosby Rosa Parks Booker T. Washington Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Jackie Robinson Louie Armstrong Wilma Rudolph Harriet Tubman Duke Ellington Black History in 1st Grade African Americans Read, Discuss, and Write about: Elijah McCoy, Booker T. Washington George Washington Carver Mathew Alexander Henson Black History in 2nd Grade Select an African American Leader Students select a partner to work with; What would you like to learn about their life? When and where were they born? Biography What accomplishments did they achieve in their life? Write 4-5 paragraphs about this person’s life Black History 3rd & 4th Graders Select a leader from the list and complete a short Biography Black History pioneer Carter Godwin Woodson Boston Massacre figure Crispus Attucks Underground Railroad leader Harriet Tubman Orator Frederick Douglass Freed slave Denmark Vesey Antislavery activist Sojourner Truth 'Back to Africa' leader Marcus Garvey Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad Legal figure Homer Plessy NAACP founder W. E. B. Du Bois Murdered civil rights activist Medgar Evers Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Civil rights leader Coretta Scott King Bus-riding activist Rosa Parks Lynching victim Emmett Till Black History 3rd & 4th Graders 'Black Power' advocate Malcolm X Black Panthers founder Huey Newton Educator Booker T. Washington Soul On Ice author Eldridge Cleaver Educator Mary McLeod Bethune Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall Colonial scientist Benjamin Banneker Blood bank pioneer Charles Drew Peanut genius George Washington Carver Arctic explorer Matthew Henson Daring flier Bessie Coleman Astronaut Guion Bluford Astronaut Mae Jemison Computer scientist Philip Emeagwali Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai Black History 3rd & 4th Graders Brain surgeon Ben Carson U.S. -

Black History Month Calendar

In honor of Black History Month, we will journey through time and learn about 20 inspiring African Americans who made an impact, and their contributions to our world today. Long before Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr. Harriet Tubman, and Rosa Parks etched their names into American History, there were so many unknown or forgotten individuals who helped make significant contributions to society. From Inventors, to educators, activists, and poets it’s so important to make sure diverse contributions are always part of our conversations about history. The best part? We can all learn and share about these contributions everyday-not just in February. To learn about each of their contributions click the images below. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday February 1st February 2nd February 3rd February 4th February 5th Dr. Carter G. Woodson Shirley Chishlom Dr. Charles Drew Katherine Johnson Benjamin Banneker “Father of Black History” “Unbought &Unbossed” “Father of Blood Banks” “Hidden Figures” “Washington D.C” Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday February 8th February 9th February 10th February 11th February 12th Harriet Powers Otis Boykin Mary McLeod Bethune Perry Wallace Bessie Coleman “Mother of African “Pacemaker Control “Pioneer in Black “Triumph” “Queen Bess” Quilting” Unit” Education” Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday February 15th February 16th February 17th February 18th February 19th Clementine Hunter Lillian Harden Chester Pierce Mamie “Peanut” Johnson Dr. Charles H. Turner “Art from Her Heart” Armstrong “Follow Chester” “Strong Right Arm” “Buzzing with Questions” “Born to Swing” Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday February 22nd February 23rd February 24th February 25th February 26th Madame CJ Walker Garret Morgan Mary H. -

The Distancing-Embracing Model of the Enjoyment of Negative Emotions in Art Reception

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2017), Page 1 of 63 doi:10.1017/S0140525X17000309, e347 The Distancing-Embracing model of the enjoyment of negative emotions in art reception Winfried Menninghaus1 Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Valentin Wagner Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Julian Hanich Department of Arts, Culture and Media, University of Groningen, 9700 AB Groningen, The Netherlands [email protected] Eugen Wassiliwizky Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Thomas Jacobsen Experimental Psychology Unit, Helmut Schmidt University/University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg, 22043 Hamburg, Germany [email protected] Stefan Koelsch University of Bergen, 5020 Bergen, Norway [email protected] Abstract: Why are negative emotions so central in art reception far beyond tragedy? Revisiting classical aesthetics in the light of recent psychological research, we present a novel model to explain this much discussed (apparent) paradox. We argue that negative emotions are an important resource for the arts in general, rather than a special license for exceptional art forms only. The underlying rationale is that negative emotions have been shown to be particularly powerful in securing attention, intense emotional involvement, and high memorability, and hence is precisely what artworks strive for. Two groups of processing mechanisms are identified that conjointly adopt the particular powers of negative emotions for art’s purposes. -

The Affective Turn, Or Getting Under the Skin Nerves: Revisiting Stelarc

Medienimpulse ISSN 2307-3187 Jg. 50, Nr. 2, 2012 Lizenz: CC-BY-NC-ND-3.0-AT The Affective turn, or Getting Under the Skin Nerves: Revisiting Stelarc Jan Jagodzinski Jan Jagodzinski konzentriert sich dabei auf das 0,3-Sekunden- Intervall, das aus neurowissenschaftlicher Sicht zwischen einer Empfindung auf der Haut und deren Wahrnehmung durch das Gehirn verstreicht. Dieses Intervall wird derzeit in der Biokunst durch neue Medientechnologien erkundet. Der bekannte Performance-Künstler Stelarc steht beispielhaft für diese Erkundungen. Am Ende des Beitrags erfolgt eine kurze Reflexion über die Bedeutung dieser Arbeiten für die Medienpädagogik. The 'affective turn' has begun to penetrate all forms of discourses. This essay attempts to theorize affect in terms of the 'intrinsic body,' that is, the unconscious body of proprioceptive operations that occur below the level of medienimpulse, Jg. 50, Nr. 2, 2012 1 Jagodzinski The Affective turn, or Getting Under the Skin Nerves: Revisiting Stelarc cognition. I concentrate on the gap of 0.3 seconds that neuroscience posits as the time taken before sensation is registered through the skin to the brain. which I maintain has become the interval that is currently being explored by bioartists through new media technologies. The well-known performance artist Stelarc is the exemplary case for such an exploration. The essay ends with a brief reflection what this means for media pedagogy. The skin is faster than the word (Massumi 2004: 25). medienimpulse, Jg. 50, Nr. 2, 2012 2 Jagodzinski The Affective turn, or Getting Under the Skin Nerves: Revisiting Stelarc The “affective turn” has been announced,[1] but what exactly is it? Basically, it is an exploration of an “implicit” body. -

Nancy Buenger Abstract

Nancy Buenger Abstract HOME RULE: EQUITABLE JUSTICE IN PROGRESSIVE CHICAGO AND THE PHILIPPINES ______________________________________________________________________________ The evolution of the US justice system has been predominantly parsed as the rule of law and Atlantic crossings. This essay considers courts that ignored, disregarded, and opposed the law as the United States expanded across the Pacific. I track Progressive home rule enthusiasts who experimented with equity in Chicago and the Philippines, a former Spanish colony. Home rule was imbued with double meaning, signifying local self-governance and the parental governance of domestic dependents. Spanish and Anglo American courts have historically invoked equity, a Roman canonical heritage, to more effectively administer domestic dependents and others deemed lacking in full legal capacity, known as alieni juris or of another’s right. Thomas Aquinas described equity as the virtue of setting aside the fixed letter of the law to expediently secure substantive justice and the common good. In summary equity proceedings, juryless courts craft discretionary remedies according to the dictates of conscience and alternative legal traditions—such as natural law, local custom, or public policy—rather than the law’s letter. Equity was an extraordinary Anglo American legal remedy, an option only when common law remedies were unavailable. But the common law was notably deficient in the guardianship of alieni juris. Overturning narratives of equity’s early US demise, I document its persistent jurisdiction over quasi-sovereign populations, at home and abroad. Equity, I argue, is a fundamental attribute of US state power that has facilitated imperial expansion and transnational exchange. Nancy Buenger Please do not circulate or cite without permission HOME RULE: EQUITABLE JUSTICE IN PROGRESSIVE CHICAGO AND THE PHILIPPINES _____________________________________________________________________________________ Progressive home rule enthusiasts recast insular and municipal governance at the turn of the twentieth century. -

A Female Factor April 12, 2021

William Reese Company AMERICANA • RARE BOOKS • LITERATURE AMERICAN ART • PHOTOGRAPHY ______________________________ 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT 06511 (203) 789-8081 FAX (203) 865-7653 [email protected] A Female Factor April 12, 2021 Celebrating a Pioneering Day Care Program for Children of Color 1. [African Americana]: [Miller Day Nursery and Home]: MILLER DAY NURSERY AND HOME...THIRTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY PROGRAM... EBENEZER BAPTIST CHURCH [wrapper title]. [Portsmouth, Va. 1945]. [4]pp. plus text on inner front wrapper and both sides of rear wrapper. Quarto. Original printed wrappers, stapled. Minor edge wear, text a bit tanned. Very good. An apparently unrecorded program of activities planned to celebrate the thirty- fifth anniversary of the founding of the Miller Day Nursery and Home, the first day care center for children of color in Portsmouth, Virginia. The center and school were established by Ida Barbour, the first African-American woman to establish such a school in Portsmouth. It is still in operation today, and is now known as the Ida Barbour Early Learning Center. The celebration, which took place on November 11, 1945, included music, devotionals, a history of the center, collection of donations, prayers, and speeches. The work is also supplemented with advertisements for local businesses on the remaining three pages and the inside rear cover of the wrappers. In all, these advertisements cover over forty local businesses, the majority of which were likely African-American-owned es- tablishments. No copies in OCLC. $400. Early American Sex Manual 2. Aristotle [pseudonym]: THE WORKS OF ARISTOTLE, THE FAMOUS PHILOSOPHER. IN FOUR PARTS. CONTAINING I. -

Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Churches of Christ Heritage Center Jerry Rushford Center 1-1-1998 Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Rushford, Jerry, "Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882" (1998). Churches of Christ Heritage Center. Item 5. http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Jerry Rushford Center at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Churches of Christ Heritage Center by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIANS About the Author ON THE Jerry Rushford came to Malibu in April 1978 as the pulpit minister for the University OREGON TRAIL Church of Christ and as a professor of church history in Pepperdine’s Religion Division. In the fall of 1982, he assumed his current posi The Restoration Movement originated on tion as director of Church Relations for the American frontier in a period of religious Pepperdine University. He continues to teach half time at the University, focusing on church enthusiasm and ferment at the beginning of history and the ministry of preaching, as well the nineteenth century. The first leaders of the as required religion courses. movement deplored the numerous divisions in He received his education from Michigan the church and urged the unity of all Christian College, A.A.