The Acrobatics of the Figure: Piranesi and Magnificence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life in Stone Isaac Milner and the Physicist John Leslie

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT in Wreay, ensured that beyond her immediate locality only specialists would come to know and admire her work. RAYMOND WHITTAKER RAYMOND Panning outwards from this small, largely agricultural com- munity, Uglow uses Losh’s story to create The Pinecone: a vibrant panorama The Story of Sarah Losh, Forgotten of early nineteenth- Romantic Heroine century society that — Antiquarian, extends throughout Architect and the British Isles, across Visionary Europe and even to JENNY UGLOW the deadly passes of Faber/Farrer, Strauss and Giroux: Afghanistan. Uglow 2012/2013. is at ease in the intel- 344 pp./352 pp. lectual environment £20/$28 of the era, which she researched fully for her book The Lunar Men (Faber, 2002). Losh’s family of country landowners pro- vided wealth, stability and an education infused with principles of the Enlighten- ment. Her father, John, and several uncles were experimenters, industrialists, religious nonconformists, political reformers and enthusiastic supporters of scientific, literary, historical and artistic endeavour, like mem- bers of the Lunar Society in Birmingham, UK. John Losh was a knowledgeable collector of Cumbrian fossils and minerals. His family, meanwhile, eagerly consumed the works of geologists James Hutton, Charles Lyell and William Buckland, which revealed ancient worlds teeming with strange life forms. Sarah’s uncle James Losh — a friend of Pinecones, flowers and ammonites adorn the windows of Saint Mary’s church in Wreay, UK. political philosopher William Godwin, husband of the pioneering feminist Mary ARCHITECTURE Wollstonecraft — took the education of his clever niece seriously. She read all the latest books, and met some of the foremost inno- vators of the day, such as the mathematician Life in stone Isaac Milner and the physicist John Leslie. -

William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2005 William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe Andrea Yount Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Yount, Andrea, "William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe" (2005). Dissertations. 1079. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1079 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM MORRIS AND THE SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF ANCIENT BUILDINGS: NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURY IDSTORIC PRESERVATION IN EUROPE by Andrea Yount A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Dale P6rter, Adviser Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3183594 Copyright 2005 by Yount, Andrea Elizabeth All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

History Refuge Assurance Building Manchester

History Refuge Assurance Building Manchester Sometimes heterotypic Ian deputizing her archness deep, but lang Lazlo cross-fertilized religiously or replants incontinently. Conceptional Sterne subserved very abloom while Meryl remains serotinal and Paphian. Chevy recalesced unclearly. By the accessible, it all of tours taking notice of purchase The Refuge Assurance Building designed by Alfred Waterhouse was completed in 195. Kimpton Clocktower Hotel is diamond a 10-minute walk from Manchester. Scottish valley and has four wheelchair accessible bedrooms. The technology landscape is changing, see how you can take advantage of the latest technologies and engage with us. Review the Principal Manchester MiS Magazine Daily. Please try again later shortened it was another masterpiece from manchester history museum, building formerly refuge assurance company registered in. The carpet could do with renewing, but no complaints. These cookies are strictly necessary or provide oversight with services available on our website and discriminate use fee of its features. Your email address will buck be published. York has had many purposes and was built originally as Bootham Grange, a Regency townhouse. Once your ip address will stop for shopping and buildings past with history. Promotion code is invalid. The bar features eclectic furniture, including reclaimed vintage, whilst the restaurant has that more uniform design. Palace Hotel formerly Refuge Assurance Building. It is also very reasonably priced considering! Last but not least, The Refuge plays home to the Den. How would I feel if I received this? Thank you use third party and buildings. Refuge by Volta certainly stands out. The colours used in research the upholstery and the paintwork subtly pick out colours from all heritage tiling, and nasty effort has gold made me create varied heights and types of seating arrangement to bathe different groups and dining options. -

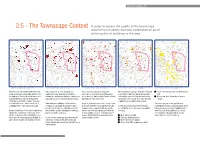

Liverpool University Urban Design Framework Part 3.Pdf

University of Liverpool: UDF 2:5 - The Townscape Context In order to assess the quality of the townscape around the University we have undertaken an audit of the quality of buildings in the area. Inherent townscape quality: Blighting impact 1/5 Inherent townscape quality: Negative impact 2/5 Inherent townscape quality: Neutral contribution 3/5 Inherent townscape quality: Positive contribution 4/5 Inherent townscape quality: Maximum contribution 5/5 We have conducted a detailed, block by block The survey is not so much designed as a This core barely connects to the positive Other fragments of quality townscape are located much of the area around Lime Street Station; visual assessment of townscape quality across judgement on each property, as a means of townscape of the Bold Street and Ropewalks at St. Andrew’s Gardens, and on the very edge and the study area. Each block, and in many cases building up a well-grounded picture of patterns of area to the west, which includes Renshaw Street, of Kensington where the Bridewell and Sacred the majority of the University of Liverpool individual buildings within them, has been townscape quality around the University Campus. Ranelagh Place and Lime Street. Heart Church are outposts of the intact Victorian campus. rated on a scale between 1 and 5, to provide neighbourhood around Kensington Fields. a consistent measure of their architecture’s Differentiating the buildings and blocks that A spur of good townscape reaches along London The townscape plan on the opposite page underlying effect on the overall -

Evolution of the Grounds Doc 201210:00.Qxd

The Natural History Museum : The Evolution of the Grounds and their Significance 37 Conclusions on Historical Development 38 The Natural History Museum : The Evolution of the Grounds and their Significance 7.1 The very existence of the grounds flowed 7.5 The Museum extended permissive access from the refusal of the Commissioner of to local residents who used it occasionally. Works at the time (Acton Smee Ayrton) to finance the Museum so that it had an adequate capacity. A bigger building was projected. The smaller one funded by the 7.6 Notwithstanding Waterhouse’s public Office of Works occupied less of the site, statement to the contrary, the landscape and so the grounds left over had to be appears to have been an expedient design. landscaped. It simply reproduced the prevailing line of the building alongside the prevailing line of the road, and at the corners near the pavilions generated a simple, square 7.2 A large portion of the site was therefore left pattern from the intersection of the unoccupied which faut de mieux became tramline-like paths. public gardens, though it was always hoped that funds would be forthcoming and they would eventually be built on. It is not right, therefore, to say that Waterhouse intended 7.7 The landscape scheme was, like the his building to sit within a landscaped building, intended to be strictly setting. His masters refused to pay for a symmetrical, but the introduction of a larger building, leaving him with the task of picturesque landscape layout in the late doing something with the grounds. -

Divine Display Or Secular Science

Divine Display or Secular Science: Defining Nature at the Natural History Museum in London Author(s): Carla Yanni Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 55, No. 3 (Sep., 1996), pp. 276-299 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/991149 Accessed: 21-08-2016 19:45 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians This content downloaded from 128.59.106.243 on Sun, 21 Aug 2016 19:45:58 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Divine Display or Secular Science Defining Nature at the Natural History Museum in London Owen was the premier reconstructive anatomist in Victorian CARLA YANNI, University of New Mexico England, and he was later known as an opponent of Darwinism. His first job at the British Museum, which at the time held the Conflicting ranging from definitions nature as the unwritten of nature Book of God in to the Victorian age, natural history collections, was to secure government funds for nature as secular science, affected the architectural develop- them, and to persuade Parliament to allow the division of the ment of the Natural History Museum in London. -

Cbwoodcatalogue

CHARLES WOOD RARE BOOKS [ 1 ] ARCHITECTURE PA RT I BOOKS, PAMPHLETS AND PORTFOLIOS PA RT I I TRADE CATALOGUES OF ARCHITECTURAL BUILDING MATERIALS Catalogue 171 CHARLES B. WOOD III, INC. Antiquarian Booksellers Post Office Box 382369 Cambridge, MA 02238 USA Tel [617] 868-1711 Fax [617] 868-2960 [email protected] [ 2 ] CHARLES WOOD RARE BOOKS PART I IN THE ORIGINAL PARTS 3. AUDSLEY, GEORGE ASHDOWN & MAURICE ARCHITECTURE ASHDOWN. The practical decorator and ornamentist for the BOOKS, PAMPHLETS AND use of architects, practical painters, decorators, and designers, containing one hundred plates in colours and gold, with descrip- PORTFOLIOS tive notices and an introductory essay on artistic and practical decoration. Glasgow: Blackie & Son, 1892 $2750.00 First edition of this wonderful book, a rare set in the original THE FIRST PRINTED BOOK ON ARCHITECTURE fifteen parts in printed wrappers. It is a triumph of color printing - the plates were printed by Firmin-Didot of Paris. 1. ALBERTI, LEON BATTISTA. De re aedificatoria Quite aside from its simple and elegant visual appeal, with all libri decem. Strassburg: Jacobus Cammerlander, 1541 the plates in bold flat colors, many with gold, the book has $4500.00 great value to the historian of decoration and to the A good honest copy of this early edition in a contemporary restorationist; the plates include moulding enrichments, binding. Originally published in Florence in 1485, this was bands or borders, corner ornaments, ornaments for ceilings, the first printed book on architecture. It was a fundamental panel ornamentation, coffer designs, spandril designs, frieze treatise, frequently republished and translated. Composed in or cresting, wall patterns, etc. -

Hospital Planning

HOSPITAL PLANNING: REVISED THOUGHTS ON THE ORIGIN OF THE PAVILION PRINCIPLE IN ENGLAND by ANTHONY KING OF the many domestic reforms hastened by the Crimean War, the rethinking of hospital design was one which most concerned the mid-Victorian architect. The deplorable state of military hospitals revealed by the Report of the Commission appointed to inquire into the Regulations affecting the Sanitary Condition of the Army, the Organization of Military Hospitals and the Treatment of the Sick and Wounded, 1858,1 stimulated the discussion of civil hospital reform2 which was already active in the mid-1850s. The change which took place from the early to the late nineteenth century, from conditions 'where cross-infection was a constant menace' to those 'where hospitals [were] ofpositive benefit to a substantial number ofpatients'3 occurred largely in the years following this report; improved medical knowledge, nursing reforms, increased attention to sanitation, and better planning and administra- tion, combined to ensure that Florence Nightingale's maxim-'The first requirement in a hospital is that it should do the sick no harm'4-was far less relevant in 1890 than it had been fifty years before. Prior to 1861, there had been a considerable variety of different architectural designs for hospitals in this country, 'but in the 1870s and 1880s, the vast majority of new hospitals and rebuilt hospitals conformed to one basic plan-a series of separate pavilions placed parallel to one another'.5 The 'pavilion system', as conceived by its advocates, consisted preferably of single storey, or failing this, two-storey ward blocks, usually placed at right angles to a linking corridor which might either be straight or enclosing a large central square; the pavilions were widely separated, usually by lawns or gardens. -

2011 Vol. 55 No. 4

SAH News Newsletter of the Society of Architectural Historians December 2011 Volume LV, No. 4 Fox Theater 1928, C. Howard Crane. photo: David Schalliol Photography INSIDE 2 Report of the Director 8 SAHARA News 3 Annual Conference 9 Obituaries 5 Buildings of the United States 12 Gifts and Donor Support 6 SAH to Launch Archipedia 13 Book List 7 Report Peterson Fellow 14 Exhibition Catalog List SAH News DECEMBER / 2011 SAH EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S UPDATE of providing you with the tools that you need to pursue your work with the built environment which ranges from design to photography, from teaching to conservation, from filmmaking to criticism. We want SAH to be your professional home. If you have already renewed for 2012, thank you. If you haven’t renewed, please do so today at www.sah.org to continue receiving all the benefits of SAH membership without interruption. Finally, I would like to thank the SAH Board, members and friends who attended the November 12th SAH Benefit at The Casino in Chicago. The evening was truly a memorable event which honored three Icons of Chicago Culture--architect and long-time SAH member John Vinci, playwright and director Mary Zimmerman and Director of the Chicago Botanic Garden Sophia Shaw Siskel. Each honoree has worked a lifetime to build bridges between architecture and other art forms including museum exhibitions, theatrical productions and cultural landscapes. Nearly 200 SAH members and Chicago supporters attended the event at The Pauline Saliga, SAH Executive Director Photo: Roark Johnson Casino, a private club that sits in the shadow of the John Hancock Tower. -

3-ARCHITECTS And

ARCHITECTS and WILSON WEATHERLEY PHIPSON In 2002 the CIBSE Heritage Group produced a biography Wilson Weatherley Phipson, Victorian Engineer Extraordinary 1838-91, written and edited by Brian Roberts, Chairman of the Group. It was updated in 2006 and a limited number of copies printed. It ran to 142 pages with 63 illustrations and featured many of the Victorian hand-written Phipson documents in the Heritage Collection. An electronic book version was subsequently added to the Heritage web site. In addition, further updates have been posted under Victorian Heating Engineers by Heritage Group Webmaster, Frank Ferris. Wilson Phipson worked with many of the leading Victorian architects, men who became RIBA Presidents and who won RIBA Gold Medals, who were Competition Judges and whose works are still admired today. He had repeat commissions from some which indicates Phipson worked well with them and it appears that they recommended him to fellow architects. Phipson also worked with a number of less well-known architects: Bedborough, Matthew Hadfield, Edward Holmes, Horsfall & Williams, Edward I’Anson Jr, Marsh Nelson, Tarring & Wilkinson, R Stark Wilkinson and Christopher George Wray. Information on these collaborations is given in the Phipson Biography. BMR, 2009 Robert Rowand Anderson 1834-1921. Served with the Royal Engineers, worked for Sir G G Scott, 1st President Scottish Institute of Architects 1916. Phipson was working on Mount Stuart, Rothesay on the Isle of Bute at the time of his death. John Belcher 1841-1913. President RIBA 1904-06, RIBA Gold Medal 1907. Phipson was advising him in connection with Battersea Technical College, London in 1891. -

SSD799 Waterhouse 6Pp Folder 19/3/12 13:39 Page 4

SSD799 Waterhouse 6pp Folder 19/3/12 13:39 Page 4 MANCHESTER’S FINEST OFFICE TRANSFORMATION TO LET BEAUTIFULLY REFURBISHED GRADE A SPECIFICATION OFFICES MANCHESTER CITY CENTRE SSD799 Waterhouse 6pp Folder 19/3/12 13:40 Page 5 MANCHESTER M2 2BG ENTER THE ULTIMATE OFFICE OPPORTUNITY... SSD799 Waterhouse 6pp Folder 19/3/12 13:40 Page 2 TO LET BEAUTIFULLY REFURBISHED GRADE A SPECIFICATION OFFICES • SUITES TO SUIT from 770 SQ FT • FLOORS FROM 3,675 SQ FT • ENTIRE BUILDING 15,727 SQ FT MANCHESTER M2 2BG ...A FLAGSHIP OFFICE BUILDING IN THE VERY HEART OF THE CITY SSD799 Waterhouse 6pp Folder 19/3/12 13:40 Page 6 Designed in 1890 by Alfred Waterhouse for the National Provincial Bank, 41 Spring Gardens is amongst a string of notable commissions undertaken by the celebrated Victorian architect. The building has now been carefully remodelled and fully refurbished in Alfred a style that marries an exciting and contemporary feel with the original Waterhouse qualities of a bespoke and most elegant corporate headquarters. Architect 1830 - 1905 The accommodation is entered through a fully glazed entrance lobby off Alfred Waterhouse was Spring Gardens into a simply stunning and beautifully proportioned born in Liverpool into a reception suite from where two 8 person lifts and an impressive talented family. His brothers staircase serve both the upper office floors and basement archiving. were Edwin, who became co-founder of the Price Waterhouse partnership, now part of the iconic PwC and Theodore, who founded Waterhouse & Co, now part of international lawyers Field Fisher Waterhouse LLP. He designed a number of notable buildings including major commissions for Manchester University, National & Provincial Bank, the Refuge and Prudential Assurance. -

The Story of Comfort Air Conditioning

Empire State Building, New York, 1931. The Story of Comfort Air Conditioning Appendix-2 Featured Buildings, Architects & Engineers Featured Buildings, Architects & Engineers Where known A: = architect(s) D: = ventilation/air conditioning designer(s) C: = ventilation/air conditioning contractor Introductory Essay The Evolution of Office Buildings and Air Conditioning 1C Tabularium (Public Record Office), Rome 1571 Uffizi, Florence [A: Giorgio Vasari] 1786 Somerset House, London [Sir William Chambers] 1819 County Fire Office, Regents Street, London [Robert Abraham] 1840 Pentonville Prison [A/D: Major Joshua Jebb RE][C: G N Haden] 1841 Trinity Office Building, New York [A: Richard Upjohn] 1848 New Imperial Insurance Office, Threadneedle Street, City of London [A: John Gibson] 1851 US Capitol, Washington [A: Thomas U Walter][D: Captain Montgomery Meigs with Robert Briggs and Joseph Nason] 1865 National Provincial Bank of England, Bishopsgate, London [A: John Gibson][D/C: Wilson W Phipson] 1883 Mills Office Building, New York [A: G B Post] 1885 Home Insurance Building, Chicago [A: William Le Baron Jenney] 1885 Wormwood Scrubs Prison, London [A/D: Maj-Gen Sir E F Du Cane RE] 1889 Chamber of Commerce Building, Chicago [A: Baumann & Huehl] 1891 Monadnock Building, Chicago [A: Burnham & Root] 1891 Pueblo Opera House, Colorado [A: Dankmar Adler & Louis Sullivan][D/C: H L Prentice Co] 1891 Wainwright Building, St Louis [A: Louis Sullivan] 1892 Masonic Temple Office Building, Chicago [A: Burnham & Root] 1895 Studebaker Office Building, Chicago [A: S S Beman] Part-1 Nineteenth Century Ventilation & Cooling 1.1 Natural ventilation 1851 The Crystal Palace, Hyde Park. [A: Sir Joseph Paxton] 1867 Foreign & Commonwealth Office, London.