Sharpe, Paley and Austin: the Role of the Regional Architect in the Gothic Revival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And an Invitation to Help Us Preserve

HISTORICAL NOTES CONT’D (3) ST.NICHOLAS, ICKFORD. This and other Comper glass can be recognised by a tiny design of a strawberry plant in one corner. Vernon Stanley HISTORICAL NOTES ON OUR is commemorated in the Comper window at the end of GIFT AID DECLARATION the south aisle, representing St Dunstan and the Venerable WONDERFUL CHURCH Bede; the figure of Bede is supposed to have Stanley’s Using Gift Aid means that for every pound you features. give, we get an extra 28 pence from the Inland Revenue, helping your donation go further. AN ANCIENT GAME On the broad window sill of the triple window in the north aisle is scratched the frame for This means that £10 can be turned in to £12.80 a game played for many centuries in England and And an invitation to help us just so long as donations are made through Gift mentioned by Shakespeare – Nine Men’s Morris, a Aid. Imagine what a difference that could make, combination of the more modern Chinese Chequers and preserve it. and it doesn’t cost you a thing. noughts and crosses. It was played with pegs and pebbles. GILBERT SHELDON was Rector of Ickford 1636- So if you want your donation to go further, Gift 1660 and became Archbishop of Canterbury 1663-1677. Aid it. Just complete this part of the application The most distinguished person connected with this form before you send it back to us. church, he ranks amongst the most influential clerics to occupy the see of Canterbury. He became a Rector here a Name: __________________________ few years before the outbreak of the civil wars, and during that bad and difficult time he was King Charles I’s trusted Address: ____________________ advisor and friend. -

The Victorian Society's Launch, Had Helped Establish Serious Academic Study of the Period

The national society for THE the study and protection of Victorian and Edwardian VICTORIAN architecture and allied arts SOCIETY LIVERPOOL GROUP NEWSLETTER December 2009 PROGRAMME CHESTER-BASED EVENTS Saturday 23 January 2010 ANNUAL BUSINESS MEETING 2.15 pm BISHOP LLOYD’S PALACE, 51-53 Watergate Row After our business meeting, Stephen Langtree will talk about the Chester Civic Trust (whose home this is) in its 50th Anniversary year. Chester Civic Trust has a high profile both locally and nationally: over the past twenty years, as secretary, chairman, now vice-president, Stephen Langtree has had much to do with this. Wednesday 17 February 7 for 7.30 pm GROSVENOR MUSEUM (Chester Civic Trust / visitors welcome / no advance booking / suggested donation £3) LIVING BUILDINGS - ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATION: PHILOSOPHY, PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE Donald Insall’s “Living Buildings” (reviewed in November’s ‘Victorian’) was recently published to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Donald Insall Associates. It was the 1968 Insall Report which proved a pioneering study for Chester’s conservation: Donald Insall CBE will reflect on this and other work of national significance (including Windsor Castle) in his lecture. Wednesday 17 March 7 for 7.30 pm GROSVENOR MUSEUM (Chester Civic Trust / visitors welcome / no advance booking / suggested donation £3) A NEW PEVSNER FOR CHESHIRE Sir Nikolaus Pevsner and Edward Hubbard launched the “Cheshire” volume in ‘The Buildings of England’ series back in 1971. Expansion and revision now brings Macclesfield-based architectural historian Matthew Hyde (working on the new volume with Clare Hartwell) to look again at Chester and its hinterland. He will consider changes in judgments as well as in the townscape over the 40 years. -

Holy Trinity Church Parish Profile 2018

Holy Trinity Church Headington Quarry, Oxford Parish Profile 2018 www.hthq.uk Contents 4 Welcome to Holy Trinity 5 Who are we? 6 What we value 7 Our strengths and challenges 8 Our priorities 9 What we are looking for in our new incumbent 10 Our support teams 11 The parish 12 The church building 13 The churchyard 14 The Vicarage 15 The Coach House 16 The building project 17 Regular services 18 Other services and events 19 Who’s who 20 Congregation 22 Groups 23 Looking outwards 24 Finance 25 C. S. Lewis 26 Community and communications 28 A word from the Diocese 29 A word from the Deanery 30 Person specification 31 Role description 3 Welcome to Holy Trinity Thank you for looking at our Are you the person God is calling Parish Profile. to help us move forward as we seek to discover God’s plan and We’re a welcoming, friendly purposes for us? ‘to be an open door church on the edge of Oxford. between heaven and We’re known as the C. S. Lewis Our prayers are with you as you earth, showing God’s church, for this is where Lewis read this – please also pray for worshipped and is buried, and us. love to all’ we also describe ourselves as ’the village church in the city’, because that’s what we are. We are looking for a vicar who will walk with us on our Christian journey, unite us, encourage and enable us to grow and serve God in our daily lives in the parish and beyond. -

Life in Stone Isaac Milner and the Physicist John Leslie

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT in Wreay, ensured that beyond her immediate locality only specialists would come to know and admire her work. RAYMOND WHITTAKER RAYMOND Panning outwards from this small, largely agricultural com- munity, Uglow uses Losh’s story to create The Pinecone: a vibrant panorama The Story of Sarah Losh, Forgotten of early nineteenth- Romantic Heroine century society that — Antiquarian, extends throughout Architect and the British Isles, across Visionary Europe and even to JENNY UGLOW the deadly passes of Faber/Farrer, Strauss and Giroux: Afghanistan. Uglow 2012/2013. is at ease in the intel- 344 pp./352 pp. lectual environment £20/$28 of the era, which she researched fully for her book The Lunar Men (Faber, 2002). Losh’s family of country landowners pro- vided wealth, stability and an education infused with principles of the Enlighten- ment. Her father, John, and several uncles were experimenters, industrialists, religious nonconformists, political reformers and enthusiastic supporters of scientific, literary, historical and artistic endeavour, like mem- bers of the Lunar Society in Birmingham, UK. John Losh was a knowledgeable collector of Cumbrian fossils and minerals. His family, meanwhile, eagerly consumed the works of geologists James Hutton, Charles Lyell and William Buckland, which revealed ancient worlds teeming with strange life forms. Sarah’s uncle James Losh — a friend of Pinecones, flowers and ammonites adorn the windows of Saint Mary’s church in Wreay, UK. political philosopher William Godwin, husband of the pioneering feminist Mary ARCHITECTURE Wollstonecraft — took the education of his clever niece seriously. She read all the latest books, and met some of the foremost inno- vators of the day, such as the mathematician Life in stone Isaac Milner and the physicist John Leslie. -

St. Paul's Church, Scotforth

St. Paul’s Church, Scotforth Contents Summary 2 Our Vision 3 Who Is God Calling? 3 The Parish and Wider Community 4 Church Organization 7 The Church Community 8 Together we are stronger 10 Our Buildings 11 The Church 12 The Hala Centre 13 The Parish Hall 14 The Vicarage 15 The Church Finances 16 Our Schools 17 Our Links into the Wider Community 20 1 Summary St Paul’s Church Scotforth is a vibrant and accepting community in Lancaster. The church building is a landmark on the A6 south of the city centre, and the vicarage is adjacent in its own private grounds. Living here has many attractive features. We have our own outstanding C of E primary school nearby with which we have strong links. And very close to the parish we also find outstanding secondary schools, Ripley C of E academy and two top-rated grammar schools. In addition Lancaster’s two universities bring lively people and facilities to the area. Traveling to and from Scotforth has many possibilities. We rapidly connect to the M6 and to the west coast main train line. Our proximity to beautiful countryside keeps many residents happy to remain. We are close to the Lake District, the Yorkshire Dales, Bowland forest, Morecambe Bay, to mention just a few such attractions. Our Church is a welcoming and friendly place. Our central churchmanship is consistent with the lack of a central aisle in our unusual “pot” church building! Our regular services (BCP or traditional, in church or in the Hala Centre) use the Bible lectionary to encourage understanding and action, but we also are keen to develop innovative forms of worship. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2013

HERITAGE AT RISK 2013 / WEST MIDLANDS Contents HERITAGE AT RISK III Worcestershire 64 Bromsgrove 64 Malvern Hills 66 THE REGISTER VII Worcester 67 Content and criteria VII Wychavon 68 Criteria for inclusion on the Register VIII Wyre Forest 71 Reducing the risks X Publications and guidance XIII Key to the entries XV Entries on the Register by local planning authority XVII Herefordshire, County of (UA) 1 Shropshire (UA) 13 Staffordshire 27 Cannock Chase 27 East Staffordshire 27 Lichfield 29 NewcastleunderLyme 30 Peak District (NP) 31 South Staffordshire 32 Stafford 33 Staffordshire Moorlands 35 Tamworth 36 StokeonTrent, City of (UA) 37 Telford and Wrekin (UA) 40 Warwickshire 41 North Warwickshire 41 Nuneaton and Bedworth 43 Rugby 44 StratfordonAvon 46 Warwick 50 West Midlands 52 Birmingham 52 Coventry 57 Dudley 59 Sandwell 61 Walsall 62 Wolverhampton, City of 64 II Heritage at Risk is our campaign to save listed buildings and important historic sites, places and landmarks from neglect or decay. At its heart is the Heritage at Risk Register, an online database containing details of each site known to be at risk. It is analysed and updated annually and this leaflet summarises the results. Heritage at Risk teams are now in each of our nine local offices, delivering national expertise locally. The good news is that we are on target to save 25% (1,137) of the sites that were on the Register in 2010 by 2015. From St Barnabus Church in Birmingham to the Guillotine Lock on the Stratford Canal, this success is down to good partnerships with owners, developers, the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), Natural England, councils and local groups. -

Harry Longueville Jones, FSA, Medieval Paris and the Heritage Measures

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bangor University Research Portal Harry Longueville Jones, FSA, Medieval Paris and the heritage measures ANGOR UNIVERSITY of the July monarchy Pryce, Huw Antiquaries Journal DOI: 10.1017/S000358151600024X PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 01/09/2016 Peer reviewed version Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Pryce, H. (2016). Harry Longueville Jones, FSA, Medieval Paris and the heritage measures of the July monarchy. Antiquaries Journal, 96, 391-314. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000358151600024X Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 09. Oct. 2020 HARRY LONGUEVILLE JONES, FSA, MEDIEVAL PARIS AND THE HERITAGE MEASURES OF THE JULY MONARCHY Huw Pryce Huw Pryce, School of History, Welsh History and Archaeology, Bangor University, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 2DG. -

The Jesse Tree Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE JESSE TREE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Geraldine Mccaughrean | 96 pages | 21 Nov 2006 | Lion Hudson Plc | 9780745960760 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The Jesse Tree PDF Book First Name. We cannot do it without your support. Many of the kings who ruled after David were poor rulers. As a maximum, if the longer ancestry from Luke is used, there are 43 generations between Jesse and Jesus. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Quite possibly this is also the forerunner of our own Christmas tree. The tree itself can be one of several types. The tree with five undulating branches carved in foliage rises from the sculptured recumbent form of Jesse. In the picture, the prophet Isaiah approaches Jesse from beneath whose feet is springing a tree, and wraps around him a banner with words upon it which translate literally as:- "A little rod from Jesse gives rise to a splendid flower", following the language of the Vulgate. Several 13th-century French cathedrals have Trees in the arches of doorways: Notre-Dame of Laon , Amiens Cathedral , and Chartres central arch, North portal - as well as the window. Jesus was a descendent of King David and Christians believe that Jesus is this new branch. I am One in a Million. Monstrance from Augsburg A late 17th-century monstrance from Augsburg incorporates a version of the traditional design, with Jesse asleep on the base, the tree as the stem, and Christ and twelve ancestors arranged around the holder for the host. Sometimes this is the only fully illuminated page, and if it is historiated i. -

William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2005 William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe Andrea Yount Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Yount, Andrea, "William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe" (2005). Dissertations. 1079. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1079 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM MORRIS AND THE SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF ANCIENT BUILDINGS: NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURY IDSTORIC PRESERVATION IN EUROPE by Andrea Yount A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Dale P6rter, Adviser Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3183594 Copyright 2005 by Yount, Andrea Elizabeth All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp

Nineteenth Ce ntury The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 37 Number 1 Nineteenth Century hhh THE MAGAZINE OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY IN AMERICA VOLuMe 37 • NuMBer 1 SPRING 2017 Editor Contents Warren Ashworth Consulting Editor Sara Chapman Bull’s Teakwood Rooms William Ayres A LOST LETTER REVEALS A CURIOUS COMMISSION Book Review Editor FOR LOCkwOOD DE FOREST 2 Karen Zukowski Roberta A. Mayer and Susan Condrick Managing Editor / Graphic Designer Wendy Midgett Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp. PERPETUAL MOTION AND “THE CAPTAIN’S TROUSERS” 10 Amityville, New York Michael J. Lewis Committee on Publications Chair Warren Ashworth Hart’s Parish Churches William Ayres NOTES ON AN OVERLOOkED AUTHOR & ARCHITECT Anne-Taylor Cahill OF THE GOTHIC REVIVAL ERA 16 Christopher Forbes Sally Buchanan Kinsey John H. Carnahan and James F. O’Gorman Michael J. Lewis Barbara J. Mitnick Jaclyn Spainhour William Noland Karen Zukowski THE MAkING OF A VIRGINIA ARCHITECT 24 Christopher V. Novelli For information on The Victorian Society in America, contact the national office: 1636 Sansom Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 636-9872 Fax (215) 636-9873 [email protected] Departments www.victoriansociety.org 38 Preservation Diary THE REGILDING OF SAINT-GAUDENS’ DIANA Cynthia Haveson Veloric 42 The Bibliophilist 46 Editorial 49 Contributors Jo Anne Warren Richard Guy Wilson 47 Milestones Karen Zukowski A PENNY FOR YOUR THOUGHTS Anne-Taylor Cahill Cover: Interior of richmond City Hall, richmond, Virginia. Library of Congress. Lockwood de Forest’s showroom at 9 East Seventeenth Street, New York, c. 1885. (Photo is reversed to show correct signature and date on painting seen in the overmantel). -

1911 the Father of the Architect, John Douglas Senior, Was Born In

John Douglas 1830 – 1911 The father of the architect, John Douglas senior, was born in Northampton and his mother was born in Aldford, Cheshire. No records have been found to show where or when his parents married but we do know that John Douglas was born to John and Mary Douglas on April 11th 1830 at Park Cottage Sandiway near Northwich, Cheshire. Little is known of his early life but in the mid to late 1840s he became articled to the Lancaster architect E. G. Paley. In 1860 Douglas married Elizabeth Edmunds of Bangor Is-coed. They began married life in Abbey Square, Chester. Later they moved to Dee Banks at Great Boughton. They had five children but sadly only Colin and Sholto survived childhood. After the death of his wife in 1878, Douglas remained at the family home in Great Boughton before designing a new house overlooking the River Dee. This was known as both Walmoor Hill and Walmer Hill and was completed in 1896. On 23rd May 1911 John Douglas died, he was 81. He is buried in the family grave at Overleigh Cemetery, Chester. Examples of the Work of John Douglas The earliest known design by John Douglas dates from 1856 and was a garden ornament, no longer in existence, at Abbots Moss for Mrs. Cholmondeley. Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, first Duke of Westminster, saw this design and subsequently became Douglas’ patron paying him to design many buildings on his estates, the first being the Church of St. John the Baptist Aldford 1865-66. Other notable works include : 1860-61 south and southwest wings of Vale Royal Abbey for Hugh Cholmondley second Baron Delamere 1860-63 St. -

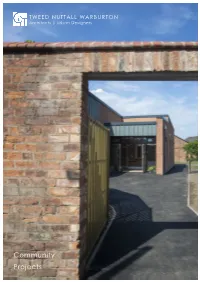

Community Projects

TWEED NUTTALL WARBURTON Architects | Urban Designers Community Projects 1 New Church Centre, Handbridge weed Nuttall Warburton has a long history of working on community projects. We believe community buildings should be designed to be flexible and accessible to all T users. The spaces should be welcoming and fit for purpose as function spaces ready for regular use and enjoyment as the center of a community. We also believe the buildings should be sustainable and provide the community with a legacy building for the years to come. We have a long association with the local community of Chester and surrounding villages. Our experienced team greatly value establishing a close Client/Architect relationship from the outset. We regularly engage with community groups and charities along with local authorities, heritage specialists and relevant consultants to ensure the process of producing a community building is as beneficial to the end users as is possible. We can provide feasibility studies to assist local community groups, charities and companies make important decisions about their community buildings. These studies can explore options to make the most of the existing spaces and with the use of clever extensions and interventions provide the centres with a new lease of life. We can also investigate opportunities for redevelopment and new purpose-built buildings. Church Halls and Community Centres Following the successful completion of several feasibility studies we have delivered a range of community centres and projects in Chester, Cheshire and North Wales. These have included: A £1.5m newbuild community centre incorporating three function spaces, a cafe and medical room for adjacent surgery all within the grounds of a Grade II* listed Church.