Sample Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Victorian Society's Launch, Had Helped Establish Serious Academic Study of the Period

The national society for THE the study and protection of Victorian and Edwardian VICTORIAN architecture and allied arts SOCIETY LIVERPOOL GROUP NEWSLETTER December 2009 PROGRAMME CHESTER-BASED EVENTS Saturday 23 January 2010 ANNUAL BUSINESS MEETING 2.15 pm BISHOP LLOYD’S PALACE, 51-53 Watergate Row After our business meeting, Stephen Langtree will talk about the Chester Civic Trust (whose home this is) in its 50th Anniversary year. Chester Civic Trust has a high profile both locally and nationally: over the past twenty years, as secretary, chairman, now vice-president, Stephen Langtree has had much to do with this. Wednesday 17 February 7 for 7.30 pm GROSVENOR MUSEUM (Chester Civic Trust / visitors welcome / no advance booking / suggested donation £3) LIVING BUILDINGS - ARCHITECTURAL CONSERVATION: PHILOSOPHY, PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE Donald Insall’s “Living Buildings” (reviewed in November’s ‘Victorian’) was recently published to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Donald Insall Associates. It was the 1968 Insall Report which proved a pioneering study for Chester’s conservation: Donald Insall CBE will reflect on this and other work of national significance (including Windsor Castle) in his lecture. Wednesday 17 March 7 for 7.30 pm GROSVENOR MUSEUM (Chester Civic Trust / visitors welcome / no advance booking / suggested donation £3) A NEW PEVSNER FOR CHESHIRE Sir Nikolaus Pevsner and Edward Hubbard launched the “Cheshire” volume in ‘The Buildings of England’ series back in 1971. Expansion and revision now brings Macclesfield-based architectural historian Matthew Hyde (working on the new volume with Clare Hartwell) to look again at Chester and its hinterland. He will consider changes in judgments as well as in the townscape over the 40 years. -

1911 the Father of the Architect, John Douglas Senior, Was Born In

John Douglas 1830 – 1911 The father of the architect, John Douglas senior, was born in Northampton and his mother was born in Aldford, Cheshire. No records have been found to show where or when his parents married but we do know that John Douglas was born to John and Mary Douglas on April 11th 1830 at Park Cottage Sandiway near Northwich, Cheshire. Little is known of his early life but in the mid to late 1840s he became articled to the Lancaster architect E. G. Paley. In 1860 Douglas married Elizabeth Edmunds of Bangor Is-coed. They began married life in Abbey Square, Chester. Later they moved to Dee Banks at Great Boughton. They had five children but sadly only Colin and Sholto survived childhood. After the death of his wife in 1878, Douglas remained at the family home in Great Boughton before designing a new house overlooking the River Dee. This was known as both Walmoor Hill and Walmer Hill and was completed in 1896. On 23rd May 1911 John Douglas died, he was 81. He is buried in the family grave at Overleigh Cemetery, Chester. Examples of the Work of John Douglas The earliest known design by John Douglas dates from 1856 and was a garden ornament, no longer in existence, at Abbots Moss for Mrs. Cholmondeley. Hugh Lupus Grosvenor, first Duke of Westminster, saw this design and subsequently became Douglas’ patron paying him to design many buildings on his estates, the first being the Church of St. John the Baptist Aldford 1865-66. Other notable works include : 1860-61 south and southwest wings of Vale Royal Abbey for Hugh Cholmondley second Baron Delamere 1860-63 St. -

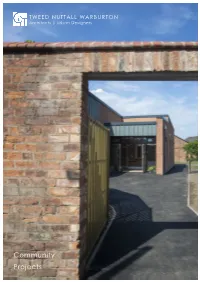

Community Projects

TWEED NUTTALL WARBURTON Architects | Urban Designers Community Projects 1 New Church Centre, Handbridge weed Nuttall Warburton has a long history of working on community projects. We believe community buildings should be designed to be flexible and accessible to all T users. The spaces should be welcoming and fit for purpose as function spaces ready for regular use and enjoyment as the center of a community. We also believe the buildings should be sustainable and provide the community with a legacy building for the years to come. We have a long association with the local community of Chester and surrounding villages. Our experienced team greatly value establishing a close Client/Architect relationship from the outset. We regularly engage with community groups and charities along with local authorities, heritage specialists and relevant consultants to ensure the process of producing a community building is as beneficial to the end users as is possible. We can provide feasibility studies to assist local community groups, charities and companies make important decisions about their community buildings. These studies can explore options to make the most of the existing spaces and with the use of clever extensions and interventions provide the centres with a new lease of life. We can also investigate opportunities for redevelopment and new purpose-built buildings. Church Halls and Community Centres Following the successful completion of several feasibility studies we have delivered a range of community centres and projects in Chester, Cheshire and North Wales. These have included: A £1.5m newbuild community centre incorporating three function spaces, a cafe and medical room for adjacent surgery all within the grounds of a Grade II* listed Church. -

The Elms Wrexham Road, Pulford Chester CH4

The Elms, Wrexham Road, Pulford, Chester The Elms double bedroom with built-in storage and en suite shower. Two further well-proportioned Wrexham Road, Pulford double bedrooms, one with a sink and the Chester CH4 9DG other with a sink and lavatory completes the accommodation. On the second floor is a further double bedroom. A detached family home with 0.88 acres in a sought-after location close to Outside Chester, with superb gardens The property is approached through twin wooden gates over a tarmacadam driveway Pulford 0.5 miles, Chester 4.6 miles, Wrexham offering parking for multiple vehicles and with 7.8 miles, Liverpool 25.8 miles, Manchester access to the detached double garage with a Airport 38.2 miles useful gardener’s cloakroom. Extending to some 0.88 acres, the well-maintained mature garden Sitting room | Drawing room | Dining room surrounding the property is laid mainly to level Kitchen | Breakfast room | Utility | Cloakroom lawn interspersed with well-stocked flowerbeds, Cellar/stores | 6 Bedrooms (2 en suite) | Garage numerous specimen shrubs and trees, a large Gardens | In all c 0.88 acres | EPC Rating E paved terrace, and a vegetable patch. The garden is screened by mature hedging, with The property views over surrounding pastureland. The Elms is an imposing period family home, in a Conservation Area, originally built c1795 Location then enlarged by John Douglas, principal The Elms sits on the northern fringes of Pulford architect for the Grosvenor Estate to provide a village, which lies to the south-west of Chester suitable residence for the Duke of Westminster’s on the England/Wales border. -

Vebraalto.Com

GREAT BUDWORTH GABLE END, SOUTHBANK CW9 6HG FLOOR PLAN (not to scale - for identification purposes only) £325,000 GREAT BUDWORTH GABLE END, SOUTHBANK ■ A Grade II listed cottage of character ■ Designed by local Architect, John Douglas 21/23 High Street, Northwich, Cheshire, CW9 5BY T: 01606 45514 E: [email protected] ■ In picturesque village of Great Budworth ■ With no ongoing chain to purchase GREAT BUDWORTH GABLE END, SOUTHBANK CW9 6HG Meller Braggins have particular pleasure in offering for sale the property known as 'Gable End' which is a distinctive and well modernised property with original leaded windows to the front elevation. With gas central heating the accommodation comprises living room, dining kitchen fitted with a range of integrated appliances and guest bedroom 2 with en-suite shower room. To the first floor there is an impressive and spacious master bedroom and a newly refurbished bathroom. Outside there is a private walled garden with the advantage of a southerly orientation. BEDROOM 1 16'8" x 14'10" (maximum) (5.08m x 4.52m (maximum)) stocked with a variety of plants and shrubs, trellis fencing, water The property is wonderfully situated in a quiet backwater of the KITCHEN DINING ROOM 16'3" (maximum) x 13'10" (4.95m (maximum) point, outside light. village and offers a lovely aspect facing the magnificent Grade 1 x 4.22m) listed St Mary and All Saints Church. The village of Great SERVICES Budworth is an idyllic location which is steeped in history and is All main services are connected. well documented in the Domesday Book. Within a short stroll is NOTE the George & Dragon public house, tennis and bowls club and a We must advise prospective purchasers that none of the fittings Church of England primary school. -

Buildings Open to View

6-9 September 2018 13-16 September 2018 BUILDINGS BUILDINGSOPEN TO OPENVIEW TO VIEW 0 2 Welcome to Heritage Open Days 2018 Heritage Open days celebrates our architecture and culture by allowing FREE access to interesting properties, many of which are not normally open to the public, as well as free tours, events, and other activities. It is organised by a partnership of Chester Civic Trust and Cheshire West and Chester Council, in association with other local societies. It would not be possible without the help of many building owners and local volunteers. Maps are available from Chester Visitor Information Centre and Northwich Information Centre. For the first time in the history of Heritage Open Days the event will take place nationally across two weekends in September the 6-9 and the 13-16. Our local Heritage Open Days team decided that to give everyone the opportunity to fully explore and discover the whole Cheshire West area Chester buildings would open on 6-9 September and Ellesmere Port & Mid Cheshire would open on 13-16 September. Some buildings/ events/tours were unable to do this and have opened their buildings on the other weekend so please check dates thoroughly to avoid disappointment. Events – Tours, Talks & Activities Booking is ESSENTIAL for the majority of HODs events as they have limited places. Please check booking procedures for each individual event you would like to attend. Children MUST be accompanied by adults. Join us If you share our interest in the heritage and future development of Chester we invite you to join Chester Civic Trust. -

Buildings Free to View

13-22 September 2019 BUILDINGS OPEN TO FREE BUILDINGSVIEW EVENTS FREE TO VIEW 0 2 Welcome to Heritage Open Days 2019 Heritage Open Days celebrates our architecture and culture by allowing FREE access to interesting properties, many of which are not normally open to the public, as well as free tours, events and activities. It is organised by a partnership of Chester Civic Trust and Cheshire West and Chester Council, in association with other local societies. It is only possible with the help of many building owners and local volunteers. Maps are available from Chester Visitor Information Centre and Northwich Information Centre. To celebrate their 25th anniversary, Heritage Open Days will take place nationally over ten days from 13 to 22 September 2019. In order to give everyone the opportunity to fully explore and discover the whole Cheshire West area, Chester buildings will mainly be open on 13 -16 September and Ellesmere Port and Mid Cheshire will mainly be open on 19-22 September. However they will also be open on other dates so please check details thoroughly to avoid disappointment. Events – Tours, Talks & Activities Booking is ESSENTIAL for the majority of HODs events as they have limited places. Please check booking procedures for each individual event you would like to attend. Children MUST be accompanied by adults. The theme for Heritage Opens Days this year is “People Power” and some of the events will be linked to this. Join us If you share our interest in the heritage and future development of Chester we invite you to join Chester Civic Trust. -

St John's Church, Sandiway

St John’s Church, Sandiway CONTENTS 3 Welcome to St John’s 4-5 About our parish 6-8 About our church 9-13 What we do now 14 What we want to do next 15 Who we are looking for “To worship God, and share his love with others.” Welcome to St John’s Thank you for enquiring about our vacancy. It's a very exciting time to be part of St John's. We are in the draft stage of a proposed major reordering project, and need a leader to help us to make decisions and take God's mission and ministry forward. St John's is a friendly welcoming church, aiming to be accessible and inclusive at the centre of our wider community. We hope you feel called to visit us. Our parish is fully supportive of women’s ministry. We are therefore seeking a vicar, male or female, who is enthusiastic about serving our community and who will enjoy playing an active part in the life of our village. Our vicar will be able to work in collaboration with our successful, wider ministry team and connect with people throughout the village, from the youngest to the oldest and lead us in continuing our journey forwards. p3 About our parish Cuddington and Sandiway today make up a wonderful village situated in mid Cheshire, a thriving place to live and work. The village is conveniently situated close to two local towns, approximately 4 miles west of Northwich and 3 miles north of Winsford. It has easy road and rail access to the cities of Chester, Manchester and Liverpool. -

Accidents at Work the Accident Claims Specialists in Chester

April 2012 - Issue 57 www.overleighroundabout.co.uk Inside this month: St Mary’s Pre-School, Edgars Field, Queen’s Park High School, , Hoolehealth PI Work and Sept2011_Layout beauty, local news1 14/09/2011 and much 17:19 more Page 1 Accidents at Work The Accident Claims Specialists in Chester Injured? Not Your Fault? Experience, expertise and excellence since 1860 You're better off with Bartletts! No Win - No Fee - Call Free! 100% Compensation Guaranteed CALL FREE: 0800 157 7923 T: 01244 313 301 To request a call back - Text: ACCIDENT to 60006 www.theaccidentspecialists.co.uk • E: [email protected] Bartletts Solicitors, 1 Frodsham Square, Frodsham Street, Chester, CH1 3JS (Next to TESCO) Members of the Association of Personal Injury Lawyers • Members of the Law Society's Personal Injury Panel • Members of the Motor Accident Solicitors Society Handbridge, Queen’s Park, Westminster Park, Curzon Park, Hough Green, Eccleston, Pulford, Dodleston & Saltney Tel 350398 E-mail [email protected] Web www.overleighroundabout.co.uk overleigh ad 127x190 jan12 12/1/12 15:22 Page 1 2 To advertise call 350398 www.overleighroundabout.co.uk Overleigh Roundabout April 2012 3 BUYING GOLD Tailored bookkeeping for small businesses l Annual accounts l Self Assessment l VAT Returns Buying both quality Matthew’s truly are the expert l Competitive hourly rates l AAT qualified Earls Way, Curzon Park - £415,000 and scrap jewellery Call Beth on local agent. Call us for a FREE, Absolute highest prices paid. 01244 679245 / 07745 575671 no obligation market evaluation FOR Looking to buy anything: Email [email protected] or advice SALE Gold and silver coins and jewellery, war medals also wanted. -

BP the Grosvenor Arms and Aldford

Uif!Hsptwfnps!Bsnt!jt!b!dibsnjnh!qvc! xjui!xfmm.tqbdfe!sppnt!bne!b!hsfbu!pvutjef! Uif!Hsptwfnps!Bsnt!bne! ufssbdf!mfbejnh!jnup!b!tnbmm!cvu!wfsz! qmfbtjnh!hbsefn/!Gspn!uif!pvutjef!ju! Bmegpse-!Diftijsf bqqfbst!b!sbuifs!bvtufsf!Wjdupsjbn! hpwfsnftt!pg!b!cvjmejnh-!cvu!pndf!jntjef!ju’t! wfsz!xfmdpnjnh/ A 2.5 mile (extendable along a riverside path) circular pub Easy Terrain walk from the Grosvenor Arms in Aldford, Cheshire. The walking route explores the village of Aldford and follows a lovely peaceful stretch of the River Dee, visiting the impressive local iron bridge on route. Aldford is an immaculately kept 19th century model estate village with a church, village hall, post office and the remains of a Norman 3/6!njmft! motte and bailey castle. Djsdvmbs!!!! Hfuujnh!uifsf 2!up!2/6! Aldford lies in the south-west corner of Cheshire, about 5 miles south of Chester, close to the border with Wales. The walk starts and finishes from the Grosvenor Arms on Chester ipvst Road. The pub has its own large car park alongside. Approximate post code CH3 6HJ. 170114 Wbml!Tfdujpnt Go 1 Tubsu!up!Tu!Kpin’t!Divsdi! Access Notes Come out of the pub car park to the main road and turn left passing in front of the pub. Keep ahead on the narrow 1. The walk is almost entirely flat and there are a pavement and over to the right you’ll see the old wooden stocks set into the wall. These are one of just a handful of few kissing gates/gates but no stiles. -

Four Eighteenth-Century Buildings at Halton

FOUR EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BUILDINGS AT HALTON A. H. Gomme, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. Halton, which a decade ago gave its ordinary-sounding name to the improbable union of Runcorn and Widnes, is, for historical architecture, quite the most interesting part of the new borough. This paper is concerned with its four most prominent survivals from the first half of the eighteenth century, three on the Brow near the church and castle and one now lost among new housing on the flat land to the south. Three of these buildings Hallwood, the parish library and the vicarage are connected with the Chesshyre family who had lived in Halton certainly as early as the sixteenth century. The present Hallwood, though it may incorporate earlier work, was probably built by Thomas Chesshyre shortly before 1660. He is described as an 'official of the Duchy of Lancaster" and may just possibly have been a lawyer, like an Elizabethan ancestor of the same name and like his once-celebrated son who was born at Hallwood in 1662.2 John Chesshyre was the fourth of five brothers and had at least one sister. He was entered at the Inner Temple in 1696 and was involved in several of the most controversial trials of the early eighteenth century, which greatly enriched him; he rose to be queen'sand, on George I' s accession, 1714, when he was knighted, king's serjeant and finally, in 1727, king's prime serjeant. He spent most of his life in London (where he owned a house in Essex Street, Strand) and in Isleworth, then a fashionable out-of-town village with numerous substantial gentry houses, one of which Chesshyre bought in 1718 and subsequently enlarged. -

Imagining Corporate Culture: the Industrial Paternalism of William Hesketh Lever at Port Sunlight, 1888-1925

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Imagining corporate culture: the industrial paternalism of William Hesketh Lever at Port Sunlight, 1888-1925 Jeremy David Rowan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Rowan, Jeremy David, "Imagining corporate culture: the industrial paternalism of William Hesketh Lever at Port Sunlight, 1888-1925" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4086. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4086 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. IMAGINING CORPORATE CULTURE: THE INDUSTRIAL PATERNALISM OF WILLIAM HESKETH LEVER AT PORT SUNLIGHT, 1888-1925 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Jeremy David Rowan B.A., Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville, 1992 M.A., Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, 1995 May 2003 Acknowledgments I first want to thank my dissertation committee. I am especially grateful for the encouragement and guidance given by my dissertation director, Meredith Veldman. Even while living across the Atlantic, she swiftly read my drafts and gave me invaluable suggestions. Additionally, I am grateful for the help and advice of the other members of my committee, Victor Stater, Maribel Dietz, Charles Royster, and Arnulfo Ramirez.