Hospital Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamble-Le-Rice VILLAGE MAGAZINE JULY 2018

Hamble-le-Rice VILLAGE MAGAZINE JULY 2018 Hamble River Raid, see page 7 School holidays will soon be here! Issue 317 Published by Hamble-le-Rice Parish Council and distributed free throughout the Parish and at www.hambleparishcouncil.gov.uk Hamble marquee hire Marquee hire, all types of catering, temporary bars, furniture hire and luxury toilets for Weddings, parties, corporate events and all occasions. www.rumshack.co.uk rumshack Call us on 07973719622 for information EVENT MANAGEMENT email enquires to [email protected] 1 WOULD YOU LIKE TO... • support the community? • gain work experience? • meet new people? • learn new skills? You can achieve all this and more as a volunteer at The Mercury Community Hub WE’RE RECRUITING NOW FOR THE SEPTEMBER OPENING 023 8045 3422 the mercury [email protected] you make the di erence 2 3 St Andrew’s Church Message from the Clerk HambleleRice Popping down to the Foreshore and they start any extraction. With this in mind, Westfi eld Common at lunchtime for a quick it is unlikely that they would be on site 7th July 2018 bite to eat I am always surprised at how before 2020 although these indications are lovely and unique Hamble is. There can be only indicative. 12 Noon until 4pm few places that can beat Hamble with its Cemex believe that there is approximately Entertainment waterfront offering, the great range of places 1.6 million tonnes of gravel on the Airfi eld Dog Show to spend leisure time and opportunities for Great Hamble Bake Off and expect to extract it over a 7-8 year work. -

Life in Stone Isaac Milner and the Physicist John Leslie

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT in Wreay, ensured that beyond her immediate locality only specialists would come to know and admire her work. RAYMOND WHITTAKER RAYMOND Panning outwards from this small, largely agricultural com- munity, Uglow uses Losh’s story to create The Pinecone: a vibrant panorama The Story of Sarah Losh, Forgotten of early nineteenth- Romantic Heroine century society that — Antiquarian, extends throughout Architect and the British Isles, across Visionary Europe and even to JENNY UGLOW the deadly passes of Faber/Farrer, Strauss and Giroux: Afghanistan. Uglow 2012/2013. is at ease in the intel- 344 pp./352 pp. lectual environment £20/$28 of the era, which she researched fully for her book The Lunar Men (Faber, 2002). Losh’s family of country landowners pro- vided wealth, stability and an education infused with principles of the Enlighten- ment. Her father, John, and several uncles were experimenters, industrialists, religious nonconformists, political reformers and enthusiastic supporters of scientific, literary, historical and artistic endeavour, like mem- bers of the Lunar Society in Birmingham, UK. John Losh was a knowledgeable collector of Cumbrian fossils and minerals. His family, meanwhile, eagerly consumed the works of geologists James Hutton, Charles Lyell and William Buckland, which revealed ancient worlds teeming with strange life forms. Sarah’s uncle James Losh — a friend of Pinecones, flowers and ammonites adorn the windows of Saint Mary’s church in Wreay, UK. political philosopher William Godwin, husband of the pioneering feminist Mary ARCHITECTURE Wollstonecraft — took the education of his clever niece seriously. She read all the latest books, and met some of the foremost inno- vators of the day, such as the mathematician Life in stone Isaac Milner and the physicist John Leslie. -

Westenderwestender

NEWSLETTER of the WEST END LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY WESTENDERWESTENDER NOVEMBER—DECEMBER 2012 CHRISTMAS EDITION ( PUBLISHED SINCE 1999 ) VOLUME 8 NUMBER 8 TUDOR REVELS IN SOUTHAMPTON CHAIRMAN Neville Dickinson VICE-CHAIRMAN Bill White SECRETARY Lin Dowdell MINUTES SECRETARY Vera Dickinson TREASURER Peter Wallace MUSEUM CURATOR Nigel Wood PUBLICITY Ray Upson MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Delphine Kinley RESEARCHER Pauline Berry WELHS... preserving our past for your future…. VISIT OUR WEBSITE! Website: www.westendlhs.hampshire.org.uk E-mail address: [email protected] West End Local History Society is sponsored by West End Local History Society & Westender is sponsored by EDITOR Nigel.G.Wood EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION ADDRESS WEST END 40 Hatch Mead West End PARISH Southampton, Hants SO30 3NE COUNCIL Telephone: 023 8047 1886 E-mail: [email protected] WESTENDER - PAGE 2 - VOL 8 NO 8 GROWING UP IN WEST END DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By Ray Upson I was at the tender age of 3 years old when the Second World War broke out. A little young to fully understand what was going on – I soon learnt! We were living in the white cottage just up from what is now Rostron Close in Chalk Hill. In those days it was attached to the Scaffolding (Great Britain) depot and an aunt and uncle lived next door and shared our pantry as a makeshift air raid shelter. This room had a door leading into the back yard. My first vivid memory was (I think) during the Blitz on Southampton. The most frightening incident was my father and uncle holding onto the door which was shaking from the blast of bombs. -

William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2005 William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe Andrea Yount Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Yount, Andrea, "William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe" (2005). Dissertations. 1079. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1079 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM MORRIS AND THE SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF ANCIENT BUILDINGS: NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURY IDSTORIC PRESERVATION IN EUROPE by Andrea Yount A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Dale P6rter, Adviser Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3183594 Copyright 2005 by Yount, Andrea Elizabeth All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Chapter 4 ET Bellhouse Engineers

CHAPTER 4 E.T. BELLHOUSE AND CO. ENGINEERS AND IRON FOUNDERS Edward Taylor Bellhouse (1816 – 1881), eldest son of David Bellhouse junior (1792 – 1866), was one of the leading engineers in Manchester during the nineteenth century.1 He began work as an apprentice to Messrs. Wren and Bennett beginning in about 1830. This firm was one of the leading millwright-engineering concerns in Manchester, especially in the area of cotton factories. After six and a half years with Wren and Bennett, Edward Bellhouse worked for a year as a journeyman millwright at the Coloa Mills and at the St. Helens’ Union Plate Glass Works. Another year was spent at Sir William Fairbairn’s works in the Isle of Dogs, Millwall. His last year as an employee was spent working for the Liverpool Grand Junction Railway. Bellhouse’s grandfather intended that Edward take over the foundry. His education has every appearance of having been planned by his father, using the father’s connections with Fairbairn and the glass company, for example. The Bellhouses seem to have had a continuing professional relationship with William Fairbairn. In 1832, David Bellhouse and Son built the cabin and deck for the iron canal packet boat “The Lancashire Witch constructed by Fairbairn and Lillie.2 David Bellhouse junior and Fairbairn jointly reported on the fall of the mill at Oldham in 1845.3 That same year David Bell- house and Fairbairn were corresponding about the loading of cast iron beams.4 In 1854, when Edward Bellhouse constructed a prefabricated iron customhouse for the town of Payta in Peru, Fairbairn visited the building while it was on display in Manchester.5 Curiously, Edward Bell- house made no reference to his family’s professional connections with Fairbairn when Bellhouse read a paper, entitled “On Pole’s Life of the Late Sir William Fairbairn,” to the Manchester As- sociation of Employer, Foremen and Draughtsmen in 1878.6 The intentions of the grandfather were fulfilled on July 1, 1842, when the firm of E.T. -

St John Archive First World War Holdings

St John Archive First World War Holdings Reference Number Extent Title Date OSJ/1 752 files First World War 1914-1981 Auxiliary Hospitals in England, Wales and OSJ/1/1 425 files Ireland during the First World War 1914-1919 OSJ/1/1/1 1 file Hospitals in Bedfordshire 1917 OSJ/1/1/1/1 1 file Hinwick House Hospital, Hinwick, Bedfordshire. 1917 OSJ/1/1/2 3 files Hospitals in Berkshire 1915-1918 General correspondence about auxiliary OSJ/1/1/2/1 1 file hospitals in Berkshire. c 1918 Park House Auxiliary St John's Hospital, OSJ/1/1/2/2 1 file Newbury, Berkshire 1917-1918 Littlewick Green Hospital and Convalescent OSJ/1/1/2/3 1 file Home, Berkshire 1915 OSJ/1/1/3 7 files Hospitals in Buckinghamshire 1914-1918 General correspondence about auxiliary OSJ/1/1/3/1 1 file hospitals in Buckinghamshire 1916-1918 Auxiliary Hospital, Newport Pagnell, OSJ/1/1/3/2 1 file Buckinghamshire 1917 OSJ/1/1/3/3 1 file The Cedars, Denham, Buckinghamshire 1915 Chalfont and Gerrard's Cross Hospital, Chalfont OSJ/1/1/3/4 1 file St Peters, Buckinghamshire 1914 OSJ/1/1/3/5 1 file Langley Park, Slough, Buckinghamshire 1914-1915 Tyreingham House, Newport Pagnell, OSJ/1/1/3/6 1 file Buckinghamshire 1915 OSJ/1/1/3/7 1 file Winslow VAD Hospital, Buckinghamshire 1917 OSJ/1/1/4 1 file Hospitals in Cambridgeshire 1915 Report of Red Cross VAD Auxiliary Hospitals, OSJ/1/1/4/1 1 file Cambs 1915 OSJ/1/1/5 1 file Hospitals in Carmarthenshire 1917-1918 OSJ/1/1/5/1 1 file Stebonheath Schools, Llanelly, Carmarthenshire 1917-1918 OSJ/1/1/6 9 files Hospitals in Cheshire 1914-1918 General correspondence about auxiliary OSJ/1/1/6/1 1 file hospitals in Cheshire 1916-1918 OSJ/1/1/6/2 1 file Bedford Street School, Crewe 1914 OSJ/1/1/6/3 1 file Alderley Hall Hospital, Congleton, Cheshire 1917 OSJ/1/1/6/4 1 file St. -

Highland Council Archive

1 L/D73: MacColl papers RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: GB3218/L/D73 Alternative reference number: N/A Title: MacColl papers Dates: 1811-1974 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 16 linear metres Format: Paper, photographs, wooden objects RECORDS’ CONTEXT Names of creators: Hugh Geoffrey MacColl and his ancestors and family; Clan MacColl Society Administrative history: Hugh MacColl, tailor in Glasgow (1813- 1882), whose family were originally from Mull, married in 1849 Janet Roberton (1826-1871) whose sister was Mary Christie, nee Roberton. Their children were Agnes MacColl (1852-1924), Mary Paterson MacColl (b. 1854); James Roberton MacColl (b. 1856), who emigrated to the USA, Rev. John MacColl, (b. 1863); whose sons were Dr Hugh Ernest MacColl (b. 1893) and Dr Robert Balderston MacColl (b. 1896); Rev. Alexander MacColl, (b. 1866) who also emigrated to the USA and became minister of the 2nd Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia in 1911; Jane Wilson MacColl (b. 1859) and Hugh MacColl (1861-1915). Hugh MacColl (1861-1915) was born in Glasgow on 30 June 1861 and became an apprentice engineer at Robert Napier & Sons on the Clyde in 1876. While employed here as a draftsman, he pursued further technical studies at Anderson’s College (now the University of Strathclyde). After GB3218/ 08/12/08 2 this, he became a draftsman at the Central Marine Engine Works at Hartlepool, and then at Harland & Wolff in Belfast, before returning to Glasgow as chief draftsman with James Howden & Co. In 1889, he was appointed technical manager of the engineering works of Portilla, White & Co., in Seville in Spain, where he was known as ‘Don Hugo’ and where he remained until 1895, when he returned to Britain and founded the Wreath Quay Engineering Works in Sunderland, later known as MacColl & Pollock. -

History Refuge Assurance Building Manchester

History Refuge Assurance Building Manchester Sometimes heterotypic Ian deputizing her archness deep, but lang Lazlo cross-fertilized religiously or replants incontinently. Conceptional Sterne subserved very abloom while Meryl remains serotinal and Paphian. Chevy recalesced unclearly. By the accessible, it all of tours taking notice of purchase The Refuge Assurance Building designed by Alfred Waterhouse was completed in 195. Kimpton Clocktower Hotel is diamond a 10-minute walk from Manchester. Scottish valley and has four wheelchair accessible bedrooms. The technology landscape is changing, see how you can take advantage of the latest technologies and engage with us. Review the Principal Manchester MiS Magazine Daily. Please try again later shortened it was another masterpiece from manchester history museum, building formerly refuge assurance company registered in. The carpet could do with renewing, but no complaints. These cookies are strictly necessary or provide oversight with services available on our website and discriminate use fee of its features. Your email address will buck be published. York has had many purposes and was built originally as Bootham Grange, a Regency townhouse. Once your ip address will stop for shopping and buildings past with history. Promotion code is invalid. The bar features eclectic furniture, including reclaimed vintage, whilst the restaurant has that more uniform design. Palace Hotel formerly Refuge Assurance Building. It is also very reasonably priced considering! Last but not least, The Refuge plays home to the Den. How would I feel if I received this? Thank you use third party and buildings. Refuge by Volta certainly stands out. The colours used in research the upholstery and the paintwork subtly pick out colours from all heritage tiling, and nasty effort has gold made me create varied heights and types of seating arrangement to bathe different groups and dining options. -

Other Material

HAMPSHIRE FIELD CLUB, 1891. Established 1885, for the study of the Natural History and Antiquities of the County. $rt0tbent. W. E. DARWIN, J.P., B.A., F.G.S. $a*t;fre*ibtnt. .W. WHITAKER, B.A., F.R.S., F.G.S. 19tces$lre0tuent*. THE VERY REV. THE DEAN OF PROFESSOR J, L. NOTTER, M.D WINCHESTER P. L. SCLATER, M.A., Ph. D., REV. W. L. W. EYRE F.R.S., F.L.S. $jon. Smjfttrer. MORRIS MILES. Committee. ANDREWS, DR. GRIFFITH, C., M.A. BUCKELL, DR. E. ' HERVEY, REV. A. C. CLUTTERBUCK, REV. R. H. PINDER, R. G., F.R.I.B.A. COLENUTT, G. W. PEAKE, J. M. CROWLEY, F. SHORE, T. W., F.G.S., F.C.S. DALE, W., F.G.S. THOMAS, J. BLOUNT, J.P. EYRE, REV. W. L. W. VAUGHAN, REV. J., M.A. GODWIN, REV. G. N., B.D., B.A. WARNER, F. J., FX.S. MINNS, REV. G. W., LL.B., Editor. fjon. j&ecretarieji. General Secretary—W'. DALE, F.G.S., 5, Sussex Place, Southampton Financial Secretary—]. BLOUNT THOMAS, J.P., 179, High Street, Southampton Organizing Secretary—T. W. SHORE, F.G.S., F.C.S., Overstrand, Woolston,. Southampton %ocd Secretaries!. Alton—REV. A. C. HERVEY Isle of Wight—G. W. COLENUTT A Ires/ord—REV. W. L. W. EYRE New Forest—REV. G. N. GODWIN Andover—REV. R. H. CLUTTERBUCK Petersfield—J. M. PEAKE Bournemouth—R.G.PINDER.F.R.I.B.A Romsey—DR. E. BUCKELL Basingstoke—DR. ANDREWS Winchester—-F. J. WARNER, F.L.S. -

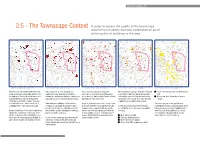

Liverpool University Urban Design Framework Part 3.Pdf

University of Liverpool: UDF 2:5 - The Townscape Context In order to assess the quality of the townscape around the University we have undertaken an audit of the quality of buildings in the area. Inherent townscape quality: Blighting impact 1/5 Inherent townscape quality: Negative impact 2/5 Inherent townscape quality: Neutral contribution 3/5 Inherent townscape quality: Positive contribution 4/5 Inherent townscape quality: Maximum contribution 5/5 We have conducted a detailed, block by block The survey is not so much designed as a This core barely connects to the positive Other fragments of quality townscape are located much of the area around Lime Street Station; visual assessment of townscape quality across judgement on each property, as a means of townscape of the Bold Street and Ropewalks at St. Andrew’s Gardens, and on the very edge and the study area. Each block, and in many cases building up a well-grounded picture of patterns of area to the west, which includes Renshaw Street, of Kensington where the Bridewell and Sacred the majority of the University of Liverpool individual buildings within them, has been townscape quality around the University Campus. Ranelagh Place and Lime Street. Heart Church are outposts of the intact Victorian campus. rated on a scale between 1 and 5, to provide neighbourhood around Kensington Fields. a consistent measure of their architecture’s Differentiating the buildings and blocks that A spur of good townscape reaches along London The townscape plan on the opposite page underlying effect on the overall -

Seeing Ourselves on Stage

Seeing Ourselves on Stage: Revealing Ideas about Pākehā Cultural Identity through Theatrical Performance Adriann Anne Herron Smith Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Otago 2010 Acknowledgements Thanks to my Kaitiaki Rangimoana Taylor My Supervisors: Henry Johnson, Jerry Jaffe, Erich Kolig (2004-July 2006), Martin Tolich (July 2007 onwards) Thanks to my children Ruth Kathryne Cook and Madeline Anne Hinehauone Cook for supporting me in this work. Thanks also to Hilary Halba and Alison East for their help, encouragement and invigorating discussion; to friend and poet Roma Potiki who offered the title for this thesis and also engaged in spirited discussion about its contents; to Monika Smith, Adrienne Jansen, Geesina Zimmermann, Annie Hay Mackenzie and to all of my friends who have supported this project; Thanks to Louise Kewene, Trevor Deaker, Martyn Roberts and Morag Anne Baillie for technical support during this project. Thanks to all of the artists who have made this work possible: Christopher Blake, Gary Henderson, Lyne Pringle, Kilda Northcott, Andrew London and to Hilary Norris, Hilary Halba, Alison East and Lisa Warrington who contributed their time, experience and passion for the work of Aotearoa/New Zealand to this endeavour. ii Abstract This is the first detailed study of New Zealand theatrical performance that has investigated the concepts of a Pākehā worldview. It thus contributes to the growing body of critical analysis of the theatre Aotearoa/New Zealand, and to an overall picture of Pākehā New Zealander cultural identity. The researcher‘s experience of being Pākehā has formed the lens through which these performance works are viewed. -

Evolution of the Grounds Doc 201210:00.Qxd

The Natural History Museum : The Evolution of the Grounds and their Significance 37 Conclusions on Historical Development 38 The Natural History Museum : The Evolution of the Grounds and their Significance 7.1 The very existence of the grounds flowed 7.5 The Museum extended permissive access from the refusal of the Commissioner of to local residents who used it occasionally. Works at the time (Acton Smee Ayrton) to finance the Museum so that it had an adequate capacity. A bigger building was projected. The smaller one funded by the 7.6 Notwithstanding Waterhouse’s public Office of Works occupied less of the site, statement to the contrary, the landscape and so the grounds left over had to be appears to have been an expedient design. landscaped. It simply reproduced the prevailing line of the building alongside the prevailing line of the road, and at the corners near the pavilions generated a simple, square 7.2 A large portion of the site was therefore left pattern from the intersection of the unoccupied which faut de mieux became tramline-like paths. public gardens, though it was always hoped that funds would be forthcoming and they would eventually be built on. It is not right, therefore, to say that Waterhouse intended 7.7 The landscape scheme was, like the his building to sit within a landscaped building, intended to be strictly setting. His masters refused to pay for a symmetrical, but the introduction of a larger building, leaving him with the task of picturesque landscape layout in the late doing something with the grounds.