Turbinella Pyrum, Linn.) and Its Relation to Hindu Life and Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

93. Sudarsana Vaibhavam

. ïI>. Sri sudarshana vaibhavam sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Annotated Commentary in English By: Oppiliappan Koil SrI VaradAchAri SaThakopan 1&&& Sri Anil T (Hyderabad) . ïI>. SWAMY DESIKAN’S SHODASAYUDHAA STHOTHRAM sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org ANNOTATED COMMENTARY IN ENGLISH BY: OPPILIAPPAN KOIL SRI VARADACHARI SATHAGOPAN 2 CONTENTS Sri Shodhasayudha StOthram Introduction 5 SlOkam 1 8 SlOkam 2 9 SlOkam 3 10 SlOkam 4 11 SlOkam 5 12 SlOkam 6 13 SlOkam 7 14 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org SlOkam 8 15 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org SlOkam 9 16 SlOkam 10 17 SlOkam 11 18 SlOkam 12 19 SlOkam 13 20 SlOkam 14 21 SlOkam 15 23 SlOkam 16 24 3 SlOkam 17 25 SlOkam 18 26 SlOkam 19 (Phala Sruti) 27 Nigamanam 28 Sri Sudarshana Kavacham 29 - 35 Sri Sudarshana Vaibhavam 36 - 42 ( By Muralidhar Rangaswamy ) Sri Sudarshana Homam 43 - 46 Sri Sudarshana Sathakam Introduction 47 - 49 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Thiruvaymozhi 7.4 50 - 56 SlOkam 1 58 SlOkam 2 60 SlOkam 3 61 SlOkam 4 63 SlOkam 5 65 SlOkam 6 66 SlOkam 7 68 4 . ïI>. ïImteingmaNt mhadeizkay nm> . ;aefzayuxStaeÇt!. SWAMY DESIKAN’S SHODASAYUDHA STHOTHRAM Introduction sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Shodasa Ayutha means sixteen weapons of Sri Sudarsanaazhwar. This sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Sthothram is in praise of the glory of Sri Sudarsanaazhwar who is wielding sixteen weapons all of which are having a part of the power of the Chak- rAudham bestowed upon them. This Sthothram consists of 19 slOkams. The first slOkam is an introduction and refers to the 16 weapons adorned by Sri Sudarsana BhagavAn. -

1 Ap1000685146 8070333 Mukku Ravichandra Reddy M

General Ranking List Of All Appeared Candidates for The Post of HOSTEL WELFARE OFFICERS GRADE-II IN A.P.TRIBAL WELFARE & B.C WELFARE (MALE & FEMALE) SUB-SERVICE Notification No 8/2019) Hall ticket PH Candidate Creamy Paper1sc Paper2s S.No OTPRId CandidateName FathersOrHusbandName GENDER Community D.O.B PH % TotalScore No Type Local Distict Layer ore core MUKKU RAVICHANDRA 1 AP1000685146 8070333 M CHINNAIAH MALE OC 1/25/1982 Prakasam NA 86.15 84.67 170.82 REDDY East 2 AP1000071702 8030045 suryam korukonda prakasa rao MALE SC 4/29/1989 NA 80.4 86 166.4 Godavari VADAKOPPULA VADAKOPPULA 3 AP1000606961 8070289 MALE BC-D 6/4/1991 Prakasam N 73.31 92.67 165.98 RAJASEKHAR GANGAIAH SHAIK MOHAMMAD SHAIK KHAJA 4 AP1000077292 8070046 MALE BC-E 2/3/1993 Prakasam N 89.19 72 161.19 RAFI NAYABRASOOL KURANGI KRANTHI 5 AP1000034775 8070025 K NARASIMHA RAO MALE OC 7/2/1981 Prakasam NA 65.2 95.33 160.53 KUMAR 6 AP1000686399 8070334 Mukku Thimmaiah Thirupathaiah MALE OC 7/1/1981 Prakasam NA 75.33 84.67 160 DURGAPRASAD East 7 AP1001068277 8030558 BABURAO MALE OC 3/2/1979 NA 68.58 91.33 159.91 MAHADASU Godavari 8 AP1000151880 8070094 NAYABRASOOL SYED MAHABOOB VALI SYED MALE OC 7/10/1988 Prakasam NA 83.79 75.67 159.46 9 AP1000455648 8070197 shaik sadhak vali sesha vali MALE BC-E 10/28/1980 Prakasam N 89.87 68.67 158.54 SAHUKARA KANTHA Visakhapat 10 AP1000004621 8020006 SAHUKARA LOCHANA FEMALE BC-D 5/6/1989 N 81.08 75.67 156.75 RAO nam 11 AP1000842784 8070388 VAMSI KRISHNA JANGA VIJAYA PRASAD MALE OC 6/20/1983 Prakasam NA 77.03 79 156.03 ANANDHA RAO Visakhapat -

Gastropods Diversity in Thondaimanaru Lagoon (Class: Gastropoda), Northern Province, Sri Lanka

Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 2021, 9, 21-30 https://www.scirp.org/journal/gep ISSN Online: 2327-4344 ISSN Print: 2327-4336 Gastropods Diversity in Thondaimanaru Lagoon (Class: Gastropoda), Northern Province, Sri Lanka Amarasinghe Arachchige Tiruni Nilundika Amarasinghe, Thampoe Eswaramohan, Raji Gnaneswaran Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Jaffna, Jaffna, Sri Lanka How to cite this paper: Amarasinghe, A. Abstract A. T. N., Eswaramohan, T., & Gnaneswa- ran, R. (2021). Gastropods Diversity in Thondaimanaru lagoon (TL) is one of the three lagoons in the Jaffna Penin- Thondaimanaru Lagoon (Class: Gastropo- sula, Sri Lanka. TL (N-9.819584, E-80.134086), which is 74.5 Km2. Fringing da), Northern Province, Sri Lanka. Journal these lagoons are mangroves, large tidal flats and salt marshes. The present of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 9, 21-30. study is carried out to assess the diversity of gastropods in the northern part https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2021.93002 of the TL. The sampling of gastropods was performed by using quadrat me- thod from July 2015 to June 2016. Different sites were selected and rainfall Received: January 25, 2020 data, water temperature, salinity of the water and GPS values were collected. Accepted: March 9, 2021 Published: March 12, 2021 Collected gastropod shells were classified using standard taxonomic keys and their morphological as well as morphometrical characteristics were analyzed. Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and A total of 23 individual gastropods were identified from the lagoon which Scientific Research Publishing Inc. belongs to 21 genera of 15 families among them 11 gastropods were identified This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International up to species level. -

2019-2020 S.No

College Ranking : 8th Rank by CCE Founders Late Duvvuru Narayana Reddy Late Duvvuru Ramanamma Founder President Late A.Syamasunder Reddy CALENDER COMMITTEE CHAIRPERSON: Dr. V. BHARATHA LAKSHMI M.Com., Ph.D. Principal (FAC) CONVENER : AEP. HANUMANTHA RAO Dr. P. KAMALA SAYI MBA M.A.,M.Phil.,Ph.D. FACULTY MEMBER STUDENT MEMBERS D. RACHANA M. DIVYA III B.Z.C. III M.C.S. MOTTO The Institution was started with noble MOTTO of "Let Noble Thoughts come to us from every side”, keeping this in mind the college always welcomes the innovative suggestions offered by the intellectuals. The college conducts spiritual classes to inculcate Spiritual values among the students to break down the social barriers and to have religious tolerance. The truths that are common to all religions are being taught to students to realize the importance of human values. Based on the saying of Swami Vivekananda the College gives priority to character building and value based education. VISION The Vision of the College is 8 To educate women about their rights and equal opportunities in all aspects of life and to raise their level of aspirations and achievements. 8 To educate women about their role in the contribution of economic and social development. 8 To improve vocational or employment related knowledge and skills. 8 To promote and encourage noble motives, objective thinking and strength of will to implement one's decisions. 8 To. make the women community to know the legitimate responsibilities in discharging their duties. 2 8 To inculcate the right attitude to accept any job or work to serve the society suitably. -

Shelled Molluscs

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) Archimer http://www.ifremer.fr/docelec/ ©UNESCO-EOLSS Archive Institutionnelle de l’Ifremer Shelled Molluscs Berthou P.1, Poutiers J.M.2, Goulletquer P.1, Dao J.C.1 1 : Institut Français de Recherche pour l'Exploitation de la Mer, Plouzané, France 2 : Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France Abstract: Shelled molluscs are comprised of bivalves and gastropods. They are settled mainly on the continental shelf as benthic and sedentary animals due to their heavy protective shell. They can stand a wide range of environmental conditions. They are found in the whole trophic chain and are particle feeders, herbivorous, carnivorous, and predators. Exploited mollusc species are numerous. The main groups of gastropods are the whelks, conchs, abalones, tops, and turbans; and those of bivalve species are oysters, mussels, scallops, and clams. They are mainly used for food, but also for ornamental purposes, in shellcraft industries and jewelery. Consumed species are produced by fisheries and aquaculture, the latter representing 75% of the total 11.4 millions metric tons landed worldwide in 1996. Aquaculture, which mainly concerns bivalves (oysters, scallops, and mussels) relies on the simple techniques of producing juveniles, natural spat collection, and hatchery, and the fact that many species are planktivores. Keywords: bivalves, gastropods, fisheries, aquaculture, biology, fishing gears, management To cite this chapter Berthou P., Poutiers J.M., Goulletquer P., Dao J.C., SHELLED MOLLUSCS, in FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE, from Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), Developed under the Auspices of the UNESCO, Eolss Publishers, Oxford ,UK, [http://www.eolss.net] 1 1. -

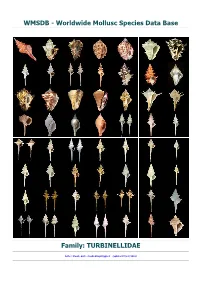

Turbinellidae

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINELLIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: CAENOGASTROPODA-HYPSOGASTROPODA-NEOGASTROPODA-MURICOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINELLIDAE Swainson, 1835 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=276, Genus=12, Subgenus=4, Species=91, Subspecies=13, Synonyms=155, Images=87 aapta , Coluzea aapta M.G. Harasewych, 1986 acuminata, Turbinella acuminata L.C. Kiener, 1840 - syn of: Latirus acuminatus (L.C. Kiener, 1840) aequilonius, Fulgurofusus aequilonius A.V. Sysoev, 2000 agrestis, Turbinella agrestis H.E. Anton, 1838 - syn of: Nicema subrostrata (J.E. Gray, 1839) aldridgei , Vasum aldridgei G.W. Nowell-Usticke, 1969 - syn of: Attiliosa aldridgei (G.W. Nowell-Usticke, 1969) altocanalis , Coluzea altocanalis R.K. Dell, 1956 amaliae , Turbinella amaliae H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874 - syn of: Hemipolygona amaliae (H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874) angularis , Coluzea angularis (K.H. Barnard, 1959) angularis , Turbinella angularis L.A. Reeve, 1847 - syn of: Leucozonia nassa (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) angularis riiseana , Turbinella angularis riiseana H.C. Küster & W. Kobelt, 1874 - syn of: Leucozonia nassa (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) angulata , Turbinella angulata (J. Lightfoot, 1786) annulata, Syrinx annulata P.F. Röding, 1798 - syn of: Pustulatirus annulatus (P.F. Röding, 1798) aptos , Columbarium aptos M.G. Harasewych, 1986 - syn of: Coluzea aapta M.G. Harasewych, 1986 ardeola , Vasum ardeola A. Valenciennes, 1832 - syn of: Vasum caestus (W.J. Broderip, 1833) armatum , Vasum armatum (W.J. Broderip, 1833) armigera , Tudivasum armigera A. Adams, 1855 - syn of: Tudivasum armigerum (A. Adams, 1856) armigera , Turbinella armigera J.B.P.A. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

a Proceedings of the United States National Museum SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION • WASHINGTON, D.C. Volume 121 1967 Number 3579 VALID ZOOLOGICAL NAMES OF THE PORTLAND CATALOGUE By Harald a. Rehder Research Curator, Division of Mollusks Introduction An outstanding patroness of the arts and sciences in eighteenth- century England was Lady Margaret Cavendish Bentinck, Duchess of Portland, wife of William, Second Duke of Portland. At Bulstrode in Buckinghamshire, magnificent summer residence of the Dukes of Portland, and in her London house in Whitehall, Lady Margaret— widow for the last 23 years of her life— entertained gentlemen in- terested in her extensive collection of natural history and objets d'art. Among these visitors were Sir Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, pupil of Linnaeus. As her own particular interest was in conchology, she received from both of these men many specimens of shells gathered on Captain Cook's voyages. Apparently Solander spent considerable time working on the conchological collection, for his manuscript on descriptions of new shells was based largely on the "Portland Museum." When Lady Margaret died in 1785, her "Museum" was sold at auction. The task of preparing the collection for sale and compiling the sales catalogue fell to the Reverend John Lightfoot (1735-1788). For many years librarian and chaplain to the Duchess and scientif- 1 2 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM vol. 121 ically inclined with a special leaning toward botany and conchology, he was well acquainted with the collection. It is not surprising he went to considerable trouble to give names and figure references to so many of the mollusks and other invertebrates that he listed. -

Elixir Journal

46093 Nilesh S. Chavan and Rahul N. Jadhav / Elixir Appl. Zoology 105C (2017) 46093-46099 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Applied Zoology Elixir Appl. Zoology 105C (2017) 46093-46099 Survey of Marine Molluscan diversity along the coasts of Shreewardhan (M.S.) Nilesh S. Chavan1 and Rahul N. Jadhav2 Department of Zoology, G.E.Society’s Arts, Commerce & Science College, Shreewardhan-402110,Dist.- Raigad. Department of Zoology, Vidyavardhini’s College of Arts, Commerce and Science, Vasai (W), Maharashtra 401202,India. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The preliminary survey of marine molluscs at 5 coasts of Shreewardhan namely Received: 23 February 2017; Shreewardhan coast, Shekhadi coast, Dive Agar coast, Sarva coast and Harihareshwar Received in revised form: coast were carried out. The occurrence of 65 species belonging to 52 genera, 35 families, 29 March 2017; 8 orders and 3 classes was noted. The Class- Gastropoda was diverse and represented by Accepted: 4 April 2017; 3 orders, 24 families, 32 genera and 42 species. Class- Scaphopoda was represented by single order, family, genus and species whereas Class- Bivalvia was represented by Keywords 4orders, 10 families, 19 genera and 22 species of molluscs. Among these 65% of the Marine, species are gastropods, 34% are bivalvia and only 1% is Scaphopoda were noted. The Molluscs, present survey indicates that Sarva coast and Shekhadi coast are diversity rich followed Diversity, by Shreewardhan coast, Harihareshwar coast and Dive Agar coast as far as molluscan Shreewardhan coasts. diversity is concerned. © 2017 Elixir All rights reserved. Introduction Sea shells play an important role in geological as well as Area of Research biological processes (Soni and Thakur,2015). -

BALABODHA SANGRAHA - 14 Sweet Memories of Our Ancient Bharatiya Agraharam and Village Streets and Life – Part 1

SANATANA DHARMA & SASTRA PRACHARA PUBLICATIONS & FREE DISTRIBUTION SERIES A Non detailed Text book for Vedic and Samskrit Students बालबोधसङ्ग्रहः – १४ BALABODHA SANGRAHA - 14 Sweet Memories of Our Ancient Bharatiya Agraharam and Village Streets and Life – Part 1 Compiled with blessings and under instructions and guidance of Paramahamsa Parivrajakacharya Jagadguru Sri Sankara Vijayendra Saraswathi Swamiji 70th Sankaracharya of Moolamnaya Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham Offered with devotion and humility by Sri Atma Bodha Tirtha Swamiji (Sri Kumbakonam Swamiji) Disciple of Ilandurai Pujyasri Kuvalayananda Tirtha Swamiji (Sri Tambudu Swamiji – Brahma Vidya Diksha Guru) and of Melakkaveri Pujyasri Panchapagesa Brahmendra Saraswathi Swamiji (Brahma Vidya Guru) Translation from Tamil by P.R.Kannan, Navi Mumbai 1 गोििन्ददेििकमुपास्यििरायभक्त्या तिस्मिन्स्थतेिनजमिहििििदेहमुक्त्या। ऄद्वैतभाष्यमुपकल्प्यददिोिििज्य काञ्चीपुरेिस्थितमिापसिङ्ग्कराययः॥ Adoring Guru Sri Govinda Bhagavatpada for long and after he attained Videhamukti through his own power, Sri Sankaracharya wrote commentaries to establish Advaita philosophy, won over opponents in all directions and finally rested in Kanchipuram, where his Avatara period concluded. (From „Patanjali Charitram‟ of Sri Ramabhadra Dikshitar) ऄपारक셁णामूर्ततज्ञानदंिान्त셂िपणम्। श्रीिन्रिेखरगु셁ंप्रणतोऽिस्ममुदान्िहम्॥ I pay obeisance every day with great happiness to Sri Chandrasekhara Guru, who is the embodiment of unlimited compassion, the bestower of Gnana, the very form of peace. (From „Guru Stuti‟ of Jagadguru -

Sandhyopaasan:The Hindu Ritual As a Foundation of Vedic Education

53| Rajendra Raj Timilsina Sandhyopaasan:The Hindu Ritual as a Foundation of Vedic Education Rajendra Raj Timilsina Abstract Yoga, meditation and Hasta Mudra Chikitsa (medication through the exercise or gesture of hands) known as spiritual activities in the past have been emerged as bases to maintain one’s health, peace and tranquility. Some people follow yoga, some focus on meditation and others apply “Hasta Chikitsa” or “Mudra”. They are separate traditional exercises. They require to spend 10 to 30 minutes once or twice a day for their optional exercise/s. It is proved that such practice has productive effect in different health treatments. This paper has applied the methods of observation, interview and literature review as qualitative paradigm in exploring their original roots of Vedic Sandhyopaasan. Twice born castes (Brahman, Chhetri and Baishya) of Nepali Hindu society has been found practicing all components of the exercises as a unified ritual of Sandhyopaasan. Upanayan (Bratabandha) ritual teaches Sandhyopaasan procedures for self control and self healing of the performers. Brahman is not eligible as Brahman without doing the ritual daily. However, this study has found that some Dalits have also been practicing Sandhyopaasan daily and feeling relaxed. Findings of this study show that Sandhyopaasan is a compact package of yoga, meditations and Hasta Chikitsa. Students and gurus of Vedas have been regularly following the compact package for inner peace and self control. Root of yoga, meditation and “Mudra” is Sandhyopaasan and this is the base of Hindu education system. The paper analyzes the ritual through Hindu educational perspective. Keywords: Sandhyopaasan, ritual, peace of mind, health, Nepali Hinduism 54| Rajendra Raj Timilsina 1. -

Check List and Occurrence of Marine Gastropoda Along the Palk Bay Region, Southeast Coast of India

Available online at www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2013, 4(1): 195-199 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Check list and occurrence of marine gastropoda along the palk bay region, southeast coast of India Elaiyaraja C, Rajasekaran R* and Sekar V. Centre of Advanced Study in Marine Biology, Faculty of Marine Sciences, Annamalai University, Parangipettai, Tamil Nadu, India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT The marine biodiversity of the southeast coast of India is rich and much of the world’s wealth of biodiversity is found in highly diverse coastal habitats. A present study was carried out on marine gastropod accessibility among Palk Bay region of Tamilnadu coastline to identify, quantify and assess the shell resources potential for development of a small-scale shell industry. A large collection of marine gastropod was made among the coastal line of Mallipattinam and Kottaipattinam found 61 species (25 families) of marine gastropods over a 12 months period from Aug- 2011 to July- 2012. A totally of 61 species belonging to 55 species of 40 genera were recorded at station 1 and 56 species belonging to 41 genera were identified at station 2. Most of the species were common in both landings centre with slight differences but some species like Turritella duplicate, Strombus canarium, Cyprae onyxadusta, Marginella angustata, and Harpa major were available in station 1 not available in station 2. The present study revealed that the occurrence of marine gastropods species along the Palk Bay region of Tamilnadu coastline. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Though marine science has established much attention in Tamilnadu coastline in the recent years, marine mollusks studies are still overseen by many researchers. -

Shell's Field Guide C.20.1 150 FB.Pdf

1 C.20.1 Human beings have an innate connection and fascination with the ocean & wildlife, but still we know more about the moon than our Oceans. so it’s a our effort to introduce a small part of second largest phylum “Mollusca”, with illustration of about 600 species / verities Which will quit useful for those, who are passionate and involved with exploring shells. This database made from our personal collection made by us in last 15 years. Also we have introduce website “www.conchology.co.in” where one can find more introduction related to our col- lection, general knowledge of sea life & phylum “Mollusca”. Mehul D. Patel & Hiral M. Patel At.Talodh, Near Water Tank Po.Bilimora - 396321 Dist - Navsari, Gujarat, India [email protected] www.conchology.co.in 2 Table of Contents Hints to Understand illustration 4 Reference Books 5 Mollusca Classification Details 6 Hypothetical view of Gastropoda & Bivalvia 7 Habitat 8 Shell collecting tips 9 Shell Identification Plates 12 Habitat : Sea Class : Bivalvia 12 Class : Cephalopoda 30 Class : Gastropoda 31 Class : Polyplacophora 147 Class : Scaphopoda 147 Habitat : Land Class : Gastropoda 148 Habitat :Freshwater Class : Bivalvia 157 Class : Gastropoda 158 3 Hints to Understand illustration Scientific Name Author Common Name Reference Book Page Serial No. No. 5 as Details shown Average Size Species No. For Internal Ref. Habitat : Sea Image of species From personal Land collection (Not in Scale) Freshwater Page No.8 4 Reference Books Book Name Short Format Used Example Book Front Look p-Plate No.-Species Indian Seashells, by Dr.Apte p-29-16 No.